Brett STEVENS

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Click here for more discussions of Archeofuturism

Click here for writings by Guillaume Faye, including an excerpt from Archeofuturism

Guillaume Faye

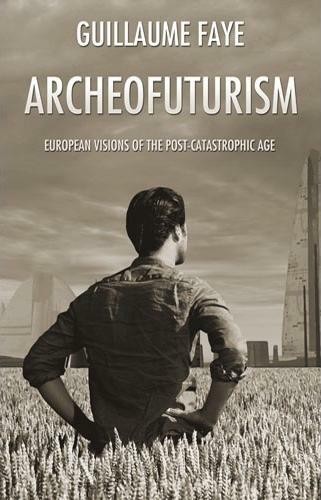

Archeofuturism: European Visions of the Post-Catastrophic Age

Arktos Media Ltd., 2010

As humans, we study our world to estimate the best responses to its demands. We then make a choice, and act on it, then observe the results to see if our estimations were correct. If they were not, we correct while trying to learn from the error. That is well and good, when buying a cement mixer — but what about a whole civilization?

As humans, we study our world to estimate the best responses to its demands. We then make a choice, and act on it, then observe the results to see if our estimations were correct. If they were not, we correct while trying to learn from the error. That is well and good, when buying a cement mixer — but what about a whole civilization?

Sometime 400 years ago, as our civilization prospered, the decision was made to modernize. This came about through a belief in the equality of all human beings and a drive toward external mechanisms, namely technology and political control systems. Guillaume Faye, the seasoned rising star of the New Right movement in Europe, explores our correction of this mistake in his landmark book Archeofuturism: European Visions of the Post-Catastrophic Age.

One of the more important things I’ve read this year, this book upholds an offhand feel throughout; an honest, end-of-the-night, when the wine and cigarettes are low and people are too tired to do anything but blurt out the big ideas that haunt them in their dreams feel. The content is dynamic, especially the first half, but the real force of power here is the style, an excitedly taboo-breaking, honest and hopeful look at re-creating ourselves so we have a future. This is not a book of resentment, but of joyful charging ahead.

A large influence on this stylistic breathlessness is the composition of the book, which is a collection of essays and a short sci-fi story to show us these ideas in practice. The second section, a thorough and high-energy explication of where Nouvelle Droite beliefs lead, the reasons for them and finally, how they can be better applied toward a theory of the future, will interest new right and deep ecologists the most as it joins the ideas of both into not a resistant/revolutionary culture but a remaking/revolutionary one.

Archeofuturism, Faye writes, escapes the boutique right-wing airy intellectualism of GRECE, which he critiques in the first book. Pointing out the failure of “ambiguous and incomprehensible ideological axes,” he proposes instead a transition from the rearward-looking “conservative” outlook to one that acknowledges what was lost, and the current state of disaster in the West, and plans for rebuilding afterward.

In his new theory of Archeofuturism, Faye proposes a “vitalist constructivism” that implements a quasi-feudal, national but not jingoistic, united Europe that applies the traditional spirit and learning to a future in which technology plays a central role. His unstated point is that the tool must again serve the man, after centuries of the reverse; he appeals to a sense of both the pragmatic in finding historically valid solutions through tradition, and the spirit of tradition, which is one of a constructive, upward society.

He proposes that we adopt this new outlook through a voluntaristic method, first changing our values, then our art, and then finally our political expectations at about the same time a “convergence of catastrophes” (environmental, political, economic) devastate Europe. Faye’s call is for Europeans to return to being “soldiers of the Idea” again, and for them to take up not a corrective action, but a constructive desire to rebuild and build it bigger, better and more exciting than before.

This fusion of both conservative and revolutionary thought takes the best of liberalism and the best of conservatism and takes them out of their handily domesticated roles as token opponents. He points out that our current ideological menu is carved from “soft ideology,” or that which passively deals with splitting up the wealth of an industrialization binge. He emphasizes a number of points all conservatives and pro-Europid readers can enjoy:

- Modernism is an attachment to the past. According to Faye, modernism is backward-looking as it tries to un-do conditions of nature that offend our egalitarian sentiment. What defines modernity is egalitarianism, or the idea that we’re all equal (in political power, in ability, in right to property). As a result, we’re constantly trying to force equality on nature while it resists us.

- Extreme leftism is a token act which reinforces the power of the modern nation-state. This point struck me as the most controversial, yet most sensible. If you are in power, and want to stay there, you need to give your citizens petty acts of rebellion that feel extreme but are in fact a repetition of the dominant philosophy. The state and its corruptors benefit from equality because it keeps smarter voices from rising above the herd.

- The modern world exists in a state of “soft totalitarianism” where those with unpopular opinions are simply ostracized, which in a liberal capitalist democracy effectively starves them into submission. He praises the American method of “soft imperialism” and shows how this is the future: indirect rule, with a reward/threat complex administered by social and business factors; the “1984″ vision is obsolete.

- Romanticism. Faye writes convincingly of his efforts to join “Cartesian classicism,” or a sense of space as being equal in all directions, with “Romanticism” which he expresses here as the idea that will or will to power can change the world radically even if small in stature. The joining of these two represents the expression of both ancient philosophy and a new type of “freedom” for humanity.

- Roots and method of modernity. Modern society consists of secularized evangelism, Anglo-Saxon mercantilism, and Enlightenment individualism, its methods are economic individualism, allegory of Progress, cult of quantitative development and abstract “human rights.” It is amazingly refreshing to see this spelled out so clearly and simply.

- Multiple factors doom modernism which was always unrealistic. “Europe is turning into a third world country,” he writes, summing up the disasters. If you see this book in a store, pick it up to read page 59 for an insightful list of modernity’s failings.

- Heterotelia. Following Nietzsche’s example, Faye needed a concept that explains how what we intend does not always result in a perpetuation of that state when put into practice. For example, political equality ends in inequality through social instability; multiculturalism ends in race war; letting economy lead ends in poverty because speculative finance is easier than generating real wealth. He explains our past failings and the need to be alert in the future through heterotelia, which means that “ideas do not necessarily yield the expected results.”

- Ethno-masochism. Faye illustrates how the West, in a suicidal bid to become morally/socially impressed with itself, has inflicted upon itself the unworkable scheme of multiculturalism and in doing so, has imported Islam, an “imperial theocratic totalitarianism.” Unlike many new right writers, he endorses the idea of European culture as superior in addition to being worth saving for its unique virtues.

- North versus South. History begins with anthropology, Faye writes, so we must see the conflict in humanity as one between Northern peoples who are prosperous, and the “third world” Southerners who are attempting to colonize the North on the back of its technology and liberal egalitarianism. He suggests a Eurosiberia stretching from the UK to the borders of China, and claims East-West conflict is less likely as a source of conflict.

Against this cataclysm Faye posits Archeofuturism, or a futurism equally balanced by the spirit of traditionalism, which is (a) learning from the past and (b) a type of reverence for life that emphasizes family, punishment being more important than prevention, duties coming before rights, solemn social rites, the aristocratic principle and a “freedom” defined not as the ability to act randomly, but as a sense of having a place and being freed from a chaotic society with excessive pointless competition. This synthesis of the best of capitalism, socialism and our monarchic past fully lives up to the title of this book.

Good luck finding a short review of this book. The first half of it is packed chock-full of interesting ideas that like new melodies can infect the head for days as it dissects them and their context. The second half both addresses common objections and provides background, and takes the form of a short science fiction story in the tradition of Asimov and Heinlein that explains how technology will help humans evolve. The concepts are mind-blowing and more daring than anything sci-fi has attempted since The Shockwave Rider, and this icing on the cake makes reading this book have a natural rhythm from the extreme, to the professorial, to the radical yet calming.

History is like a supertanker ship; it takes miles to begin to turn around and there are no brakes. The egalitarian experiment in Europe is only a few centuries old yet has wreaked utter havoc on all the subtler parts of existence, things that most people don’t notice because they are easily distracted by shiny objects. Faye brings these alive, shows us exactly why they are endangered, and then shows us a plausible and gradual (e.g. non apocalyptic, non-Utopian) solution toward which we can move if we believe life is worth saving. Clearly he does, and it infuses this book with a fervor and wisdom that few attain.

Source: http://www.amerika.org/books/archeofuturism-european-visi...

Another review of . . .

Guillaume Faye’s Archeofuturism

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Click here for more discussions of Archeofuturism

Click here for writings by Guillaume Faye, including an excerpt from Archeofuturism

Guillaume Faye

Archeofuturism: European Visions of the Post-Catastrophic Age

Arktos Media Ltd., 2010

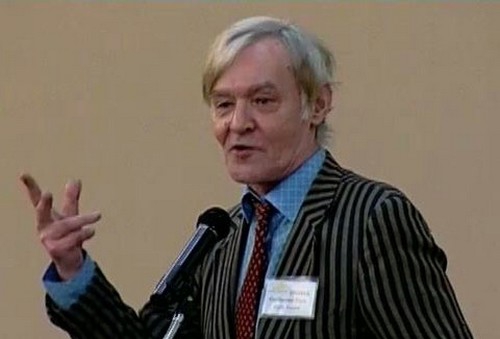

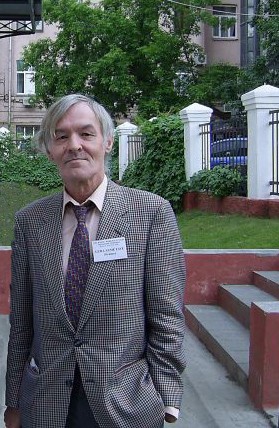

In the 1980s Guillaume Faye was one of the best known member of GRECE and by far their most popular speaker. With humour, panache, invective and contempt thrown in at just the right moment-the dismissive “l’acteur Reagan” the contemptuous and venomous “monsieur Henri Levi surnommé le grand”, he had his audiences rolling in the aisles with delight. Every time I heard him speak at a GRECE conference he received a standing ovation.

In the 1980s Guillaume Faye was one of the best known member of GRECE and by far their most popular speaker. With humour, panache, invective and contempt thrown in at just the right moment-the dismissive “l’acteur Reagan” the contemptuous and venomous “monsieur Henri Levi surnommé le grand”, he had his audiences rolling in the aisles with delight. Every time I heard him speak at a GRECE conference he received a standing ovation.

GRECE was not only a school of thought, it was also a sort of social club, linking like-minded persons on a cultural, political and social level. However, its concentration on theory made the temptation in hard times great indeed to retreat from direct confrontation and reduce all issues to the level of academic debate. Faye explicates these and other criticisms in Archeofuturism (now available for the first time in English from the Arktos Press at the same time as it has become hard to obtain in the original French).

Structure

Archeofuturism suffers from coming from the pen of a man more at home before a gathering than a keyboard. It is unbalanced and paradoxically, given the content, in some respects extremely provincial and theoretical in its approach and design. At the same time, it owes nothing to the respectability and detachment from reality which can make cowards of many writers.

This is not to say that the book lacks structure. It has a very definite if unorthodox structure. It consists of three theses as Faye calls them: (1) the end of civilization as we know it owing to what Faye calls a “convergence of catastrophes”; (2) the necessity for revolution, notably in the European mindset, (3) propositions for the post-catastrophic world (and the title of his book expresses the essence of Faye’s solution).

The last chapter is a piece of science fiction, a story of a world in which the conflict of technics and tradition has been resolved by reconciling the two, and this is the underlying thread of Faye’s entire argumentation, that we must learn to reach back to our furthest yesterday and to the longest future.

Positions

One issue is the conflict between tradition and progress. On the one hand, technology is necessary as a tool of our will to power, something which Faye believes essential to the survival of the European. On the other hand, scientific and technical progress may prove and often does prove, destructive of tradition. Are religions just fables? It is hard to die for a fable. How is such belief possible in a world of scientific rationalism and progress?

Faye believes strongly that the world is hurtling towards multi-faceted disaster, less a clash of civilizations, although he seems to write at times in a similar vein to Huntington, with his view of Islam especially as a challenge in itself to the hegemony of European civilization, than what he terms a “convergence of catastrophes.” Like Huntington, Faye regards Islam as a single cultural, religious, political bloc with a an expansionist will.

On homosexuality :

. . . it is not a matter of advocating any repression of homosexuality, of banning homosexual couples or socially penalizing gay people; simply, the prospect of legalizing of a form of marriage for homosexuals would have a highly destructive symbolic value. Marriage and legal heterosexual unions enjoy forms of protection and public benefits that are accorded to couples capable of having children and hence of renewing the generations and thus of being of objective service to society. Legalising homosexual unions and awarding them financial privileges means protecting sterile unions. (pp. 106–107)

On demographics:

It is necessary to reflect on the issue of immigration, which represents a form of demographic colonization of Europe at the hands of mostly Afro-Asiatic peoples. . . . Three generations later, the colonization of Europe represents a form of revenge against European colonization . . . are we to accept or reject a substantial alteration oif the ethno-cultural substrate of Europe? The basis of intellectual honesty and the key to ideological success lie in the ability and courage to address the real problems, instead of attempting to avoid them. (p. 49)

On distraction:

The system only makes use of brutal censorship in very limited areas: it generally resorts to intellectual diversion, i.e. distraction, by constantly focusing people’s attention on side issues. What we are dealing with here is not simply the usual brutalization of the population via the increasingly specific mass-media apparatus of the society of spectacle — a veritable audiovisual Prozac-but rather a concealment of essential political problems (immigration, pollution, transportation policies, the aging of the population, the financial crisis of the social budgets expected to occur by 2010 etc. (p. 92)

Archeofuturism

It is a sad paradox, and one about which Faye is acutely aware in his book, that the European New Right in general has failed to make an impact at the very time that the march of events might have been expected to play into its hands: the end of the cold war, the decline of political Manicheanism (East versus West) , the decline of nationalism as a relevant political alternative to liberalism. Faye offers a number of explications for this failure. They can be summarized as a lack of media “savvy”, romantic isolationism, minimization of catastrophe, cultural relativism and a lack of understanding of and worse, interest in, economics (Faye alone among spokesmen of GRECE had written a treatise on economics).

Faye’s response is to deviate from the consensus among the new right and to insist on European exceptionalism. He returns to what might be called a traditional belief of the radical right when he claims, as he does here, that European civilization is superior to others and that as a superior civilization it has a duty to resist the challenge of immigration in general and Islam in particular. Cultural and racial superiority was the premise (sometimes asserted, sometimes unspoken) of all movements of the twentieth and nineteenth centuries which sought to preserve or halt a decline in the domination of the white man over the political destiny of the globe.

European radical right movements after the Second World War focused their propaganda very much on the restoration of national prestige and glory and a rejection of immigrants and outsiders. GRECE stressed from the beginning the importance of what it called “the right to be different” arguing less in terms of European superiority than in terms of European uniqueness, Europe’s right to the nurture of its own identity and destiny. The great enemy was seen not so much as military or political threats as such, as the forces which sought to attenuate, reduce, trivialize and ultimately abolish differences. The great enemy in this respect was neither Islam nor communism but “the American way of Life,” the manifest destiny to reduce all peoples to consumers, whose sole struggles were ones of economic competition.

This developed in the course of time within GRECE into a position of ethnopluralism, which Faye and others subsequently denounced as cultural relativism. Simply put, it is the argument that all cultures are worthy of respect within their own terms and no culture is inherently superior to another. The obvious critique of such a position is that it ultimately disarms all willingness to disallow, challenge or oppose other cultures. Opposition even in its politest non-military form, can only be conducted on the premise that in some way one is superior or equipped with superior arguments or in the area of culture and religion, possesses a truer, superior culture and religion and one thereby and therewith seeks an opponent’s defeat.

There is another aspect — that of economic survival. A major criticism which Faye has of GRECE is that it ignores or glosses over demographic and economic warfare against the European. Faye argues that at a time of emergency, when Europe is threatened with being overwhelmed by non-Europeans whose demographics are reducing the significance of the European by the hour, it is a form of suicide to indulge in culturally relativist reflections and debate.

Faye spends no time in fleshing out his arguments about superiority and in what respects the European is “superior.” This is a pity because it would provide the book with a stabilizing effect. As it is, Faye assures us that he believes the European is superior and rushes on the next point. What Faye implies although I did not find it in this book explicitly stated, is that when we talk about the right of a people not only to an identity but to a destiny, there is likely to be a conflict between the destiny of a people compelled to expand and conquer and the right of another (conquered) people to an identity.

The notion of a “right” be it to identity or destiny is problematic: where does our “right” come from? A Nietzschean, as Faye claims to be, can answer this question. It could be baldly stated as the right to survival — the impulse of nature which all beings have the “right” to practice. Rights to be different are likely to conflict with the rights of others to be different. The right to conflict is therefore the right to survival of identity and it is Faye’s point that such a right can only be preserved by those who actively engage in the politics (as all politics in Faye’s view must be) of conflict. A defense of the identity of the European necessitates entering into a state of conflict with the prevailing hegemony.

Faye candidly states that he made the same mistake as other GRECE members in the expression of cultural relativism and an accompanying primary and fundamental anti-Americanism which took precedence over the ethnic question and the challenge of non-white immigration to Europe, (and presumably, the decline in relative numbers and influence of the Caucasian in North America). The “ethnopluralist” approach is exemplified by Alain de Benoist’s Europe-Tiers Monde: Même Combat where de Benoist argues that Europe and the Third World (even the term seems a little outdated today) are natural allies against the American and Soviet ways of life. Faye stresses that GRECE (and he willingly includes himself here) ignored the reality of the Islamic threat and that ethnopluralism paved the way for an inactive, “head in the sand” response to the long term significance of massive Mohammedan immigration into Europe.

Faye’s stress on the superiority of Europe in place of the right of Europeans to be different indeed avoids the danger of degenerating into an ineffective and compromising inactive pluralism. On the other hand, it shifts the focus of intent significantly towards a provocative, inevitably conflict laden project which is dear to Faye: the Eurasian Imperium. Faye is for better or for worse an imperialist. His vision of the future as outlined in this book is one of a vast Eurasian bloc, stretching from Lisbon to Vladivostok.

The implied direction, never explicitly stated of the archeofuturist project, is combat and conquest in a world divided into major power blocs jockeying for position. “Like in the Middle Ages or Antiquity, the future requires us to envisage the Earth as structured in vast, quasi-imperial unity in mutual conflict or cooperation.” (p. 77). Seen in this light, Faye’s admiration for atomic power implied in this work (and more explicitly indicated elsewhere, dramatically in his comic book Notre avant guerre, where he gleefully depicts a degenerate Europe being destroyed in mushroom clouds ) and futuristic technology in general is the ghost in the machine of Faye’s project.

However, unlike most modernizers, Faye does not duck the dilemma of reconciling a world of modern technology with a world of tradition, be it racial, political or other. How does one reconcile advanced technology and its implications with the preservation of continuity with the past? Faye faces this problem head on and if his solution is seems questionable and Utopian, he deserves the credit of highlighting the dilemma. Practically all radical rightists of whatever hue, fail to address the issue at all. Faye’s solution is what he calls “archeofuturism” the title of his book and the project to which he believes European revolutionaries (and Faye believes we must be revolutionaries to save European civilization and not conservatives) the assimilation of the future with the past, building a future not as modern or post modern but archeo-modern, a modernism acutely aware of and with its roots in a deep and profound past.

There will be a small elite of rulers with access to the highest forms of modern technology while the majority of less gifted will make do with crude forms of technical accomplishment-a completely two tier society in fact. This may sound familiar and not perhaps pleasantly so. It is this reviewer’s belief, one shared by many, that the ultimate aim of the ruling elite is the same: the division of mankind into two groups-the elite and the great majority of outsiders who no longer have a say in how public affairs are administered. This seems difficult to reconcile with Faye’s expressed support for populist initiatives. Be that as it may, this writer’s strength is his ability to fire the right questions rather than provide well prepared answers.

The “post catastrophic” world will be one, Faye believes, divided between the futuristic achievements of an elite and the archaic conditions and status of the majority, it will be archeofuturistic. Before we examine this idea more closely, it is worth taking a moment to consider the notions of growth and progress which Faye dismisses as overhauled. His chapter revealingly entitled “For a Two-Tier World Economy” opens with the bald assertion: “Progress” is clearly a dying idea, even if economic growth may be continuing”.

Anti-Growth

Faye’s rejection of what he calls “the paradigm of economic development” is simple:

An intellectual revolution is taking place: people are starting to perceive, without daring to openly state it, that the old paradigm according to which the life of humanity on both an individual and collective level is getting better and better every day thanks to science, the spread of democracy and egalitarian emancipation is quite simply false. . . . Today, the perverse effects of mass technology are starting to make themselves felt: new resistant viruses, the contamination of industrially produced food, shortage of land and a downturn in world agricultural production, rapid and widespread environmental degradation, the development of weapons of mass destruction in addition to the atomic bomb-not to mention that technology is entering its Baroque age. (pp. 162–63).

The last comment excepted (which is pure Spengler), this writing must strike the impartial reader as familiar. It is a fairly good example of the pessimism of environmentalist writers in general and it has been said many times before. Faye knows or should know, that there are very many people who are deeply aware of the heavy price which we are paying for making Progress our Baal. Faye is entirely right in my opinion, as thousands of others before him have been right, to question the cost but anyone expecting Faye to so much as nod with respect in the direction of the many organizations, groups, campaigns and initiatives to reverse this trend, will be disappointed.

On the contrary, Faye contemptuously dismisses the French Green movement in these words, “the political platform of the Green movement contain no real environmentalist suggestions, such as the transport of lorries by train instead of on highways, the creation of non-polluting cars (electric cars, LPG, etc.) or the fight against urban sprawl into natural habitats, liquid manure leaks, ground water contamination, the depletion of European fish stocks, chemical food additives, the overuse of insecticides and pesticides, etc. Each time I have tried to bring these specific and concrete issues up with a representative of the Greens, I got the impression that he was not really interested in them or that he had not really studied them” (p. 145). It is not clear (possibly a fault of the translator’s) whether Faye is referring to one or several spokesmen. Be that as it may, it is not my experience at all that environmentalists are not interested in these issues.

Futurism

Faye gives the impression throughout the book less of someone proposing ideas in a book for a wide readership as enjoying a discussion with someone who was with him in the days of GRECE over a “ballon de rouge” in a Paris café. Despite his provincialism, Faye has a sound instinct for homing in on some of the genuinely important issues of our time and viewing them in a global perspective, even when (and this is often the case here) his global perspective is obscured by the incidental historical luggage which weighs his book down. The reader should not be deterred by the book’s incidental references from letting Faye lead to key issues of our time and demanding our response to core questions.

The greatest quality of this book is that it gives a voice to the growing sense of frustration that is felt among persons form all walks of life that we are living in a transitory period, that the “end of history” is an utter illusion and that old structures are insufficient to contain the force of history. Faye cites the unlikely figure of Peter Mandelson as an “archeofuturist without knowing it” as someone who has recognized that democracy as we know it from the Mother of Parliaments is tired and no longer able to cope with the challenges which European man and indeed humankind is facing.

Faye’s examination of the real issues behind the palaver of most contemporary politicians is refreshing. Here is a taste:

The new societies of the future will finally abolish the aberrant egalitarian mechanism we have now, whereby everyone aspires to become an officer or a cadre or a diplomat, even though all evidence suggests that most people do not have the skills to fulfill those roles. This model engenders widespread frustration, failure and resentment. The societies that will be vivified by increasingly sophisticated technologies, in contrast, will ask for a return to the archaic and inegalitarian and hierarchical norms, whereby a competent and meritocratic minority is rigorously selected to take on leading assignments.

Those who perform subordinate functions in these inegalitarian societies will not feel frustrated: their dignity will not be called into question, for they will accept their own condition as something useful within the organic community-finally freed from the individualistic hubris of modernity, which implicitly and deceptively states that each person can become a scientist or a price.

“Individualistic hubris” indeed sums up for this reviewer one of the great malaises of our time: the exaggerated importance which mediocre individuals attach to their own boring lives. Faye at his best is very good indeed.

For all its failings this book is a valuable contribution to the growing awareness of persons of European descent of their time of crisis. It provides a highly readable and often acute observations about what Faye stresses are the real issues of our time but the question nags steadily: to what extent has Faye provided a strategy for Europeans in the face of those issues? The answer is that there is no strategy, unless by “strategy” we mean a positioning (for example in favor of European federalism vis-à-vis reactionary nationalism or friendly competitiveness with the United States rather than blanket hostility to the American way of life).

Perhaps someone much younger than either Faye or this reviewer will read this book and know that they are able to provide that response. In that case, this book will have shown itself to be of the past and the future, in a word archeofuturistic.

Source: http://www.amerika.org/texts/archeofuturism-by-guillaume-...

Un blog avec les articles de Guillaume Faye en espagnol:

Un blog avec les articles de Guillaume Faye en espagnol: