par Nicolas Bonnal

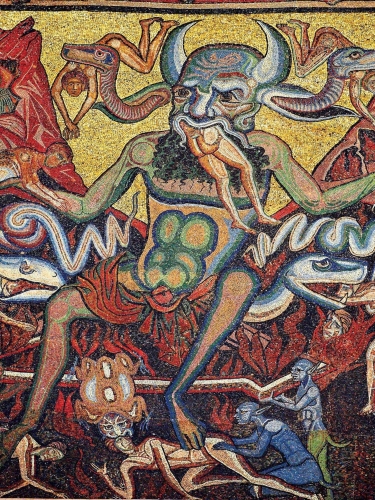

On a vu avec Castaneda l’importance des prédateurs qui se sont emparés de la terre et nous sucent comme des bonbons. Ils se nourrissent de notre énergie psychique (disons pour satisfaire les imbéciles que tout cela est une métaphore littéraire, OK ?). Le vaccin planétaire, le Reset et autres abominations technologiques, écologiques et territoriales nous ont fait basculer dans une ultra-réalité cauchemardesque basée sur la terreur, la pénurie, la connexion neuronale et l’hypnose. Hannibal Genséric a consacré un texte passionnant sur les liens de la grippe et de l’électricité, de la guerre de 14 et de la grippe soi-disant espagnole. J’ai expliqué dans un texte souvent repris que la crétinisation est venue avec la technologie, le premier à l’avoir senti et décrit fut Villiers de l’Ile-Adam (Contes cruels).

Lovecraft admirait beaucoup Maupassant. Nous aussi : Maupassant dans le Horla décrit cette intrusion extraterrestre avec un bateau marchand (ah, la mondialisation, ah, les exportations, ah, les belles usines…) qui remonte la Seine. Mais il décrit aussi TOUJOURS DANS LE HORLA la crétinisation du peuple parisien par le patriotisme (Céline fera pareil). Et cela donne ces lignes sans pareilles et jamais lues comme toujours (ah, l’école…) :

14 juillet. – Fête de la République. Je me suis promené par les rues. Les pétards et les drapeaux m’amusaient comme un enfant. C’est pourtant fort bête d’être joyeux, à date fixe, par décret du gouvernement. Le peuple est un troupeau imbécile, tantôt stupidement patient et tantôt férocement révolté. On lui dit : « Amuse-toi. » Il s’amuse. On lui dit : « Va te battre avec le voisin. » Il va se battre. On lui dit : « Vote pour l’Empereur. » Il vote pour l’Empereur. Puis, on lui dit : « Vote pour la République. » Et il vote pour la République. »

Le peuple technophile et moderne est bête-manipulé mais ses élites sont fanatiques-dangereuses. Maupassant :

« Ceux qui le dirigent sont aussi sots ; mais au lieu d’obéir à des hommes, ils obéissent à des principes, lesquels ne peuvent être que niais, stériles et faux, par cela même qu’ils sont des principes, c’est-à-dire des idées réputées certaines et immuables, en ce monde où l’on n’est sûr de rien, puisque la lumière est une illusion, puisque le bruit est une illusion. »

Dans Les dimanches d’un bourgeois de Paris Maupassant tape aussi sur la république et les élections. Et cela donne :

« Reste le suffrage universel. Vous admettez bien avec moi que les hommes de génie sont rares, n’est-ce pas ? Pour être large, convenons qu’il y en ait cinq en France, en ce moment. Ajoutons, toujours pour être large, deux cents hommes de grand talent, mille autres possédant des talents divers, et dix mille hommes supérieurs d’une façon quelconque. Voilà un état-major de onze mille deux cent cinq esprits. Après quoi vous avez l’armée des médiocres, qui suit la multitude des imbéciles. Comme les médiocres et les imbéciles forment toujours l’immense majorité, il est inadmissible qu’ils puissent élire un gouvernement intelligent. »

Et d’ajouter sur les députés :

« Autrefois, quand on ne pouvait exercer aucune profession, on se faisait photographe ; aujourd’hui on se fait député. Un pouvoir ainsi composé sera toujours lamentablement incapable ; mais incapable de faire du mal autant qu’incapable de faire du bien. Un tyran, au contraire, s’il est bête, peut faire beaucoup de mal et, s’il se rencontre intelligent (ce qui est infiniment rare), beaucoup de bien. »

Maupassant est libertarien en fait :

« Entre ces formes de gouvernement, je ne me prononce pas ; et je me déclare anarchiste, c’est-à-dire partisan du pouvoir le plus effacé, le plus insensible, le plus libéral au grand sens du mot, et révolutionnaire en même temps, c’est-à-dire l’ennemi éternel de ce même pouvoir, qui ne peut être, de toute façon, qu’absolument défectueux. Voilà. »

Dans Bel-ami l’auteur français le plus lu dans le monde durant un siècle écrivait :

« Il espérait bien réussir en effet à décrocher le portefeuille des Affaires étrangères qu’il visait depuis longtemps. C’était un de ces hommes politiques à plusieurs faces, sans conviction, sans grands moyens, sans audace et sans connaissances sérieuses, avocat de province, joli homme de chef-lieu, gardant un équilibre de finaud entre tous les partis extrêmes, sorte de jésuite républicain et de champignon libéral de nature douteuse, comme il en pousse par centaines sur le fumier populaire du suffrage universel. Son machiavélisme de village le faisait passer pour fort parmi ses collègues, parmi tous les déclassés et les avortés dont on fait des députés. Il était assez soigné, assez correct, assez familier, assez aimable pour réussir. Il avait des succès dans le monde, dans la société mêlée, trouble et peu fine des hauts fonctionnaires du moment. »

Depuis que nous sommes sous l’emprise de ses prédateurs dépourvus d’imagination (Castaneda) ou de cette modernité techno-sulfureuse, le Temps est, comme je ne cesse de le dire immobile. Même la mode disait Debord n’a plus bougé et ne bougera plus : costard-cravate. Et nous vivons dans un cercle d’informations abrutissantes et répétées. Debord :

« La construction d’un présent où la mode elle-même, de l’habillement aux chanteurs, s’est immobilisée, qui veut oublier le passé et qui ne donne plus l’impression de croire à un avenir, est obtenue par l’incessant passage circulaire de l’information, revenant à tout instant sur une liste très succincte des mêmes vétilles, annoncées passionnément comme d’importantes nouvelles ; alors que ne passent que rarement, et par brèves saccades, les nouvelles véritablement importantes, sur ce qui change effectivement. Elles concernent toujours la condamnation que ce monde semble avoir prononcée contre son existence, les étapes de son autodestruction programmée. »

Mais revenons au Horla et aux prédateurs. On a l’impression que Castaneda a lu et plagié Maupassant. Car le dernier maître de notre littérature (très grand inspirateur des deux plus grands génies du cinéma américain, Raoul Walsh et John Ford – la diligence…) écrit:

« Ah ! le vautour a mangé la colombe ; le loup a mangé le mouton ; le lion a dévoré le buffle aux cornes aiguës ; l’homme a tué le lion avec la flèche, avec le glaive, avec la poudre; mais le Horla va faire de l’homme ce que nous avons fait du cheval et du bœuf : sa chose, son serviteur et sa nourriture, par la seule puissance de sa volonté. Malheur à nous ! »

Ensuite on entre carrément dans la SF. Je vous laisse retrouver des titres de films (mon préféré est le classique de Don Siegel sur les body snatchers) et je cite :

« Mais celui qui me gouverne, quel est-il, cet invisible ? cet inconnaissable, ce rôdeur d’une race surnaturelle ?

Donc les Invisibles existent ! Alors, comment depuis l’origine du monde ne se sont-ils pas encore manifestés d’une façon précise comme ils le font pour moi ? Je n’ai jamais rien lu qui ressemble à ce qui s’est passé dans ma demeure. Oh ! si je pouvais la quitter, si je pouvais m’en aller, fuir et ne pas revenir. Je serais sauvé, mais je ne peux pas. »

Hitler a parlé dans Hitler m’a dit de Rauschning (je sais, c’est un faux, etc.) de ses visions du dur surhomme qui l’effrayaient. Maupassant :

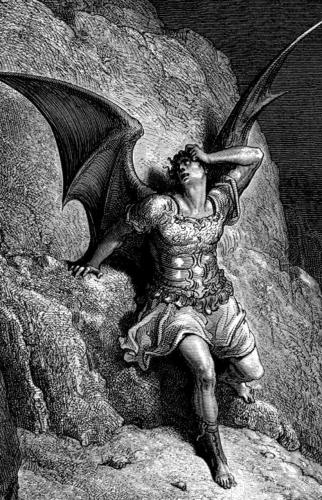

« On dirait que l’homme, depuis qu’il pense, a pressenti et redouté un être nouveau, plus fort que lui, son successeur en ce monde, et que, le sentant proche et ne pouvant prévoir la nature de ce maître, il a créé, dans sa terreur, tout le peuple fantastique des êtres occultes, fantôme vagues nés de la peur… »

Après le narrateur fait allusion au grand espace :

« Pas de lune. Les étoiles avaient au fond du ciel noir des scintillements frémissants. Qui habite ces mondes ? Quelles formes, quels vivants, quels animaux, quelles plantes sont là-bas ? Ceux qui pensent dans ces univers lointains, que savent-ils plus que nous ? Que peuvent-ils plus que nous ? Que voient-ils que nous ne connaissons point ? Un d’eux, un jour ou l’autre, traversant l’espace, n’apparaîtra-t-il pas sur notre terre pour la conquérir, comme les Normands jadis traversaient la mer pour asservir des peuples plus faibles ? »

Et il cite la presse ce narrateur (le conditionnement par la presse est la clé de l’involution spirituelle puis psychique depuis cinq siècles – relisez Macluhan) :

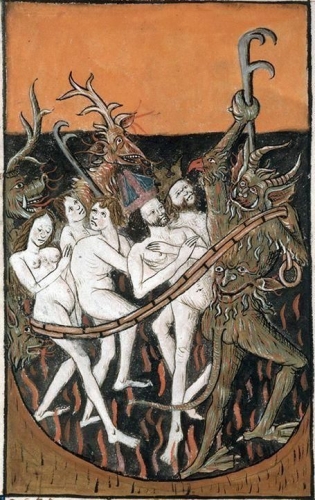

« Une nouvelle assez curieuse nous arrive de Rio de Janeiro. Une folie, une épidémie de folie, comparable aux démences contagieuses qui atteignirent les peuples d’Europe au moyen âge, sévit en ce moment dans la province de San-Paulo.

Les habitants éperdus quittent leurs maisons, désertent leurs villages, abandonnent leurs cultures, se disant poursuivis, possédés, gouvernés comme un bétail humain par des êtres invisibles bien que tangibles, des sortes de vampires qui se nourrissent de leur vie, pendant leur sommeil, et qui boivent en outre de l’eau et du lait sans paraître toucher à aucun autre aliment. »

Ici on est très proche du film Prédateur ; car la petite paysanne indienne explique qu’un diable venu de l’espace venait dans sa jeunesse manger les hommes. Le savant ufologue Jean-Pierre Petit a fait état d’observations en ce sens dans plusieurs de ses livres :

« Il est venu, Celui que redoutaient les premières terreurs des peuples naïfs, Celui qu’exorcisaient les prêtres inquiets, que les sorciers évoquaient par les nuits sombres, sans le voir apparaître encore, à qui Les pressentiments des maîtres passagers du monde prêtèrent toutes les formes monstrueuses ou gracieuses des gnomes, des esprits, des génies, des fées, des farfadets. »

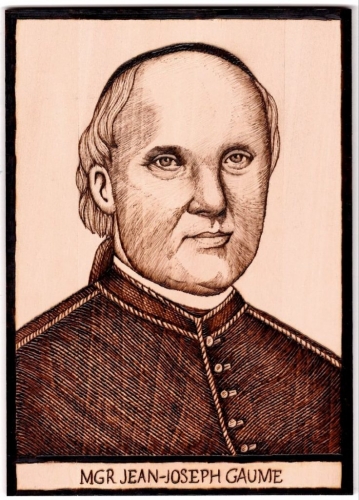

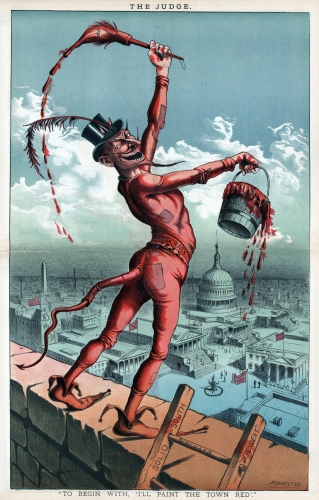

Ce qui m’intéresse en conclusion c’est de souligner que le fantastique – comme la crétinisation industrielle et typographique-médiatique – s’est développé avec la révolution industrielle, technologique et médiatique, comme si nous avions en notre époque troublée lâché et absorbé des forces méphitiques, comme ce qui était annoncé du reste dans l’Apocalypse. J’ai cité Monseigneur Gaume qui a très bellement parlé pour nous éclairer de « boucherie des âmes » pour expliquer ce qui se passe en nous depuis le temps des Lumières…

Et je vous recommande pour terminer de pratiquer la discipline de Castaneda ainsi que la relecture de mon livre sur Littérature et conspiration…

Sources :

http://achard.info/debord/CommentairesSurLaSocieteDuSpect...

http://maupassant.free.fr/pdf/horla.pdf

https://www.dedefensa.org/article/le-pokemon-et-la-cretin...

https://numidia-liberum.blogspot.com/2020/05/covid-arnaqu...

Enfin la crapulerie des élites et leur hostilité fait qu’on se désintéresse de la politique :

Enfin la crapulerie des élites et leur hostilité fait qu’on se désintéresse de la politique :

J’ai décidé depuis de rependre le même admirable livre de René Guénon, Orient et Occident (1924) pour tenter de voir avec ce grand traditionaliste ce qui ne va pas depuis si longtemps, et ce qu’il faudrait faire.

J’ai décidé depuis de rependre le même admirable livre de René Guénon, Orient et Occident (1924) pour tenter de voir avec ce grand traditionaliste ce qui ne va pas depuis si longtemps, et ce qu’il faudrait faire. Chez Guénon intellectuel désigne en fait le spirituel théologique, la capacité de parler sérieusement de Dieu et du monde spirituel. A l’époque cela décline déjà (mais en relisant Huizinga, on découvrirait que le quatorzième siècle n’était déjà pas très brillant). Guénon rajoute :

Chez Guénon intellectuel désigne en fait le spirituel théologique, la capacité de parler sérieusement de Dieu et du monde spirituel. A l’époque cela décline déjà (mais en relisant Huizinga, on découvrirait que le quatorzième siècle n’était déjà pas très brillant). Guénon rajoute : Nous découvrons (c’est la fameuse théorie de la conspiration conspuée partout et menacée par le néo-totalitarisme ambiant) que l’on nous a menti sur nous (croisades, lune, guerres, épidémies, etc.) ; or Guénon le dit déjà très bien :

Nous découvrons (c’est la fameuse théorie de la conspiration conspuée partout et menacée par le néo-totalitarisme ambiant) que l’on nous a menti sur nous (croisades, lune, guerres, épidémies, etc.) ; or Guénon le dit déjà très bien :  Cela ressemble bien à la guerre occulte décrite par Julius Evola dans les Hommes au milieu des ruines. Nietzsche a très bien écrit à ce sujet dans sa deuxième considération actuelle sur l’Histoire : l’historien est un journaliste qui adapte au goût trivial du jour les temps anciens que l’on ne comprend pas ou plus.

Cela ressemble bien à la guerre occulte décrite par Julius Evola dans les Hommes au milieu des ruines. Nietzsche a très bien écrit à ce sujet dans sa deuxième considération actuelle sur l’Histoire : l’historien est un journaliste qui adapte au goût trivial du jour les temps anciens que l’on ne comprend pas ou plus.  Puis il souligne le caractère moraliste aberrant (Nietzsche parle d’hystérie féminine chez l’Occidentale moderne dans Par-delà le bien et le mal : voyez la septième partie intitulée Nos vertus) qui progresse avec le culte du fric et du profit :

Puis il souligne le caractère moraliste aberrant (Nietzsche parle d’hystérie féminine chez l’Occidentale moderne dans Par-delà le bien et le mal : voyez la septième partie intitulée Nos vertus) qui progresse avec le culte du fric et du profit : Puis Guénon devient presque trivial (Guénon, trivial ?!) : ce que l’Orient voudrait c’est qu’on lui foute la paix !

Puis Guénon devient presque trivial (Guénon, trivial ?!) : ce que l’Orient voudrait c’est qu’on lui foute la paix !

J’adore ce passage sur le père impossible en Amérique (on n’y est pas un son of a bitch pour rien) :

J’adore ce passage sur le père impossible en Amérique (on n’y est pas un son of a bitch pour rien) :  La liquidation du père est générale : Lipovetsky avait décrit le déclin du père musulman en France dès les années 80 en France (relisez l’imposante Ere du vide) ; elle a été facilitée par les modes, la création/manipulation de la sous-culture et la musique destinée à la jeunesse - et aujourd’hui par la technologie qui crée des barrières infranchissables entre technophiles et « petits vieux » de quarante ans. Smart-siphonnés et Tik toqués sont dans leur monde.

La liquidation du père est générale : Lipovetsky avait décrit le déclin du père musulman en France dès les années 80 en France (relisez l’imposante Ere du vide) ; elle a été facilitée par les modes, la création/manipulation de la sous-culture et la musique destinée à la jeunesse - et aujourd’hui par la technologie qui crée des barrières infranchissables entre technophiles et « petits vieux » de quarante ans. Smart-siphonnés et Tik toqués sont dans leur monde.  « Personne ne prescrit au citoyen ce qu’il doit penser, croire ou éprouver. Mais, soit les Américains ont vendu cette liberté pour le plat de lentilles de la conformité, si bienfaisante, soit ils n’en ont jamais fait usage. Dans un cas comme dans l’autre, le résultat est le même : le moindre quotidien de province de l’Europe à l’ouest du rideau de fer vous donne plus d’informations sur la situation mondiale qu’il n’est possible d’en obtenir aux États-Unis. »

« Personne ne prescrit au citoyen ce qu’il doit penser, croire ou éprouver. Mais, soit les Américains ont vendu cette liberté pour le plat de lentilles de la conformité, si bienfaisante, soit ils n’en ont jamais fait usage. Dans un cas comme dans l’autre, le résultat est le même : le moindre quotidien de province de l’Europe à l’ouest du rideau de fer vous donne plus d’informations sur la situation mondiale qu’il n’est possible d’en obtenir aux États-Unis. » Comme le froncé de Macron (cf. mon texte sur le « peuple nouveau »), l’américain de Watzlawick ne veut que se fondre dans la masse, vivre et penser comme tout le monde (Tocqueville ou Francis Parker Yockey ont écrit des lignes flamboyantes à ce sujet, comme Georges Duhamel) :

Comme le froncé de Macron (cf. mon texte sur le « peuple nouveau »), l’américain de Watzlawick ne veut que se fondre dans la masse, vivre et penser comme tout le monde (Tocqueville ou Francis Parker Yockey ont écrit des lignes flamboyantes à ce sujet, comme Georges Duhamel) : On a l’impression d’une comédie screwball ou les mariés/fiancés/partenaires ne sont que deux acteurs qui parlent vite en se/nous cassant les oreilles : on reverra les classiques casse-têtes de Howard Hawks à ce sujet qui célèbrent des couples d’acteurs-amants-bateleurs sans enfants.

On a l’impression d’une comédie screwball ou les mariés/fiancés/partenaires ne sont que deux acteurs qui parlent vite en se/nous cassant les oreilles : on reverra les classiques casse-têtes de Howard Hawks à ce sujet qui célèbrent des couples d’acteurs-amants-bateleurs sans enfants.