Mitch Horowitz

Mitch Horowitz

The Miracle Club: How Thoughts Become Reality

Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions, 2018

“I don’t want to be a product of my environment. I want my environment to be a product of me. . . . When you decide to be something, you can be it. That’s what they don’t tell you in the church.”[1] [2]

The latest meme promulgated by the Dissident Right, which seems to be driving the Ctrl-Left and its media mouthpieces even more crazy than they were by Pepe the Frog, is the NPC [3] (Non-Player Character). And why shouldn’t it? It’s funny because it’s true. But it’s also more common than the 4Chan crowd might think.

As Mitch Horowitz says at the beginning of The Miracle Club, “the basic sense of human identity,” at least since Shakespeare expressed it in Macbeth, has been pretty much indistinguishable from the NPC:

Each of us “plays his part,” living, serving, struggling, until “mere oblivion.” We sometimes bring a ripple of change to our surroundings. . . . But overall, we remain bound to a familiar pattern.

Just one modern idea[2] [4] has “suggested that we are not ‘merely players,’ but also possess a creative agency”: thoughts are causative. As Neville Goddard, whom Horowitz considers the greatest figure of this alternative school of thought, says:

It is my belief that all men can change the course of their lives. By our imagination, by our affirmations, we can change our world, we can change our future. I have always preached that if we strive passionately to embody a new and higher concept of ourselves, then all things will be at our service. Most men are totally unaware of the creative power of imagination and invariably bow before the dictates of “facts” and accepts life on the basis of the world without. But when you discover this creative power within yourself, you will boldly assert the supremacy of imagination and put all things in subjection to it.[3] [5]

This is the uniquely American thought-phenomenon called “New Thought” (how American a name!), which should be regarded, as I’ve argued in a number of essays, [4] [6] as our homegrown Hermeticism, native Neoplatonism, and two-fisted Traditionalism.[5] [7]

Yet for almost a century now, New Thought has been the punchline and punching bag of everyone from learned scholars and hard-nosed scientists, to journalists looking for a feature full of cheap laughs.[6] [8] As religious scholar Jeffrey J. Kripal says in his blurb for Horowitz’s book:

The American lineage of mind metaphysics, or positive thinking, takes a beating from both the religious right and the intellectual left, who seem to share in little other than this fear and loathing of the possibility that we might actually be able to imagine ourselves into other realities, histories, and humanities.

Indeed, not only the “religious” Right; concurrent with the NPC meme, another frequently-encountered theme among the “Alt Right” of late is the disparagement of “magical thinking,” presented as something unique to the Left,[7] [9] despite the election of Donald J. Trump, a devotee of Normal Vincent Peale’s “Positive Thinking.”[8] [10] One is tempted to respond in the Trump persona: “I’m the billionaire president, and you’re not. You’re fired!”

At least one cause – or effect? – of this mockery has been that New Thought hasn’t been seriously studied since William James (who both studied and practiced what he called “the religion of healthy-edness”) died in 1910; and, as a consequence, New Thought itself hasn’t intellectually developed. [9] [11]

Comes now Mitch Horowitz[10] [12] to move the discussion of this very American stream of thought onto that very American methodological ground of proof by experience. In short, try it!

By this strategy, Horowitz first reaches back to evoke the original Miracle Club, a gathering of esoteric experimenters who banded together in New York City back in 1875, when their President received a mysterious letter reading, “Don’t give up thy club. TRY.” And in the end, he will propose that the reader join him in a new, informal miracle club.

But “club” also suggests, to me at least, Baron Julius Evola, who ran his own series of magical clubs, UR and KRUR, back in the 1920s.[11] [13] Moreover, after disbanding these groups, he founded a periodical titled La Torre (The Tower); in his autobiography, he notes that:

Backlash followed – and not because of the doctrinal or cultural content of the magazine (which, given its elevated standard, was largely ignored by Fascists), but on account of one rubric entitled ‘The Bow and the Club’ (‘L’arco e la clava’: where the bow strikes at a distance, the club does so only within range of one’s hands).[12] [14]

Without pressing the analogy too far, I would suggest that Horowitz has set himself a similar task: to deal with the far (skeptics and scientific materialists) and the near (the all-too-frequently naïve and even childish proponents of “The Secret” or “The Law of Attraction”)[13] [15] to arrive at a true, rectified picture of New Thought: “For all its shortcomings, and for all its being disparaged by critics as a dogma of wishful delusion, New Thought, in its essentials, is true – and can be tested in your experience.”

First, some terminological matters:

Some colleagues have cautioned me that terms like positive thinking seem old-fashioned and musty; the phrase puts off younger or more sophisticated readers. But the “power of positive thinking,” to use the title phrase of Peale’s 1952 book, has so fully entered the public mind that most people have an immediate association with it. It is plain. For that reason I have continued to use Peale’s phraseology, musty or not.

I am also wary of jettisoning old terms, such as ESP, New Age, and occult, simply because they have taken on critical baggage, and one hopes to arrive at something more “respectable.”

Here, too, the note is Evolian; the latter had no hesitation to use the term “magic,” despite its modern “show business” connotations; not even, like Crowley, adding a “k”.

As another, even more important preliminary, Horowitz is quick to emphasize that he writes as a participant-observer. While acknowledging the need for some level of objectivity, he rightly points out that we are quite used to, for instance, histories of Mormonism written by Mormons, or accounts of the Inquisition, say, written by Roman Catholics. And if we are to prove a method by experience – otherwise, in what sense are we being empirical? – then we must have these experiences. “The perspective of the critics requires leavening by experience. But experience will not touch the staunchest among them simply because they avoid participation in ideas.”

Even worse than professionally skeptical scientists are the half-baked journalists. Some, like Tom Wolfe, will express some sympathy with these ideas in private, but for public consumption fear it to be too infra dig to do their reputation any good. Others, like Lewis Lapham – who went all the way to India to hang out with the Beatles and the Maharishi, and even got a mantra, but couldn’t be bothered, then or in the ensuing fifty years, to actually try meditation – seem to exhibit what René Guénon considered to be a typical “Western mental distortion”: to prefer the theory of knowledge to knowledge itself.[14] [16]

As a participant-observer, Horowitz starts, appropriately enough, with himself. At some point those journalists, or TV producers, or academics, will ask him: “You don’t believe this stuff, do you?” Yes, he does:

I believe that thinking, in a directed, highly focused, and emotively charged manner, expands our capacity to perceive and concretize events, and relates us to a nontactile field of existence that surpasses ordinarily perceived boundaries of time and thought.

Or, even more concretely:

Your mind is a creative agency, and the thoughts with which you impress it contribute to the actualized events of your existence.

This is less a doctrine than a “line of experimentation” that he invites the reader to join in with. In any event, New Thought has been very good for Mitch Horowitz. In fact, despite being the son of a bankrupt Long Island attorney, he’s now a millionaire! Ordinarily, I wouldn’t bring up such personal matters, but he talks about it himself, quite openly and out of the gate. It’s actually a legitimate part of his participant/observer model.

And why not talk about money and success? One of the most basic, and laziest criticisms, of New Thought has been to deplore it as “materialistic.” Horowitz is having none of that. Although he believes in “labor unions, moderately redistributive tax policies, and personal thrift,” he also knows that we live in a material world, and we need money to obtain power, and thus to be able to actualize our basic desires.

Horowitz deplores the “recycle[d] ideas from the Vedic and Buddhist traditions,” such as “nonattachment” or “transcendence,” which have been “cherry-picked from religious structures that were . . . highly stratified and hierarchical” and which “would have regarded social mobility almost as unlikely as space travel.”[15] [17]

This ersatz “Easternism” . . . has not provided Westerners with a satisfying response to materialism because it often seeks to divert the individual from the very direction in which he may find meaning, which is toward the compass point of achievement.

My conviction is that the true nature of life is to be generative. I believe that in order to be happy, human beings must exercise their fullest range of abilities – including the exertions of outer achievement.

I believe that the simplest and most resounding truth on the question of the inner life and attainment appears in the dictum of Christ: “Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s and render unto God what is God’s.”

I do not view nonattachment as a workable goal for those of us raised in the West, and elsewhere, today. Rather, I believe that the ethical pursuit of achievement holds greater depth, and summons more from within our inner natures, than we may realize.

Although Horowitz seems to assume this is a function of the modern, globalized world (“the West and elsewhere, today”), I would suggest that this is actually true of something uniquely, essentially, and timelessly Western: what Spengler, and others after him, have called Faustian Man.[16] [18] And this is another point of contact with the work of Evola, who argued that both original Buddhism and Taoism were essentially Aryan paths to personal power.[17] [19]

Horowitz himself sees a connection with Nietzsche and . . . Ayn Rand.

New Thought at its best and most infectious celebrates the primacy of the individual. Seen in a certain light, the mystical teacher Neville Goddard, the New Thought figure whom I most admire, was a kind of spiritualized objectivist. Or perhaps I could say that Ayn Rand, the founder of philosophical Objectivism, and an ardent atheist, was a secularized Neville.

How can this be?

The motivated person must select among the possibilities and circumstances of reality.[18] [20] In their view, the individual is solely responsible, ultimately, for what he does with his choices. Rand saw this selection as the exercise of personal will and rational judgment; Neville saw it as vested in the creative instrumentalities of your imagination. But both espoused the same principle: the world that you occupy is your own obligation.[19] [21]

Speaking of obligation, having “promised you a philosophy of results,” Horowitz feels obligated to provide early on “two vital, inner steps to opening yourself to money.” The first – I’ll let you read the book to find the second – could have come from Howard Roark himself:

Speaking of obligation, having “promised you a philosophy of results,” Horowitz feels obligated to provide early on “two vital, inner steps to opening yourself to money.” The first – I’ll let you read the book to find the second – could have come from Howard Roark himself:

You must know exactly what you want to accomplish, and you must feel it passionately, even obsessively. You must be willing to turn aside everything and everyone who doesn’t contribute to your realization for that aim. . . . If that strikes you as ruthless or extreme, it is because you do not yet possess, or are not yet honest about, your definite aim. When you find it, it will be like finding breath itself.

As Neville insisted, your desires are clues given to you by God, to guide your actions in life, and should be followed without guilt, modesty, or shame. And they can be realized, precisely because they accord with the will of God, the greatest power in the universe, who is ultimately “your own wonderful human imagination.”[20] [22]

In a key chapter, “The Centrality of Neville Goddard,” Horowitz expands on his earlier precis of New Thought, presenting a three-step method, based on Neville’s many books and lectures:

First, clarify a sincere and deeply felt desire. Second, enter a state of relaxed immobility, bordering on sleep. Third, enact a mental scene that contains the assumption and feeling of your wish fulfilled. Run the little drama over and over in your mind until you experience a sense of fulfillment. Then resume your life. Evidence of your achievement will unfold at the right moment in your outer experience.

As I’ve noted before, this is exactly the method that Evola espoused in his magickal writings; first, create an image of the desired state, then:

In order for any image to act in the way I am talking about, it must be loved. It must be assumed in a great, inner calm and then warmed up, almost nourished, with sweetness, without bringing the will or any effort into play, and much less without expectations.[21] [23] The Hermeticists called this agent “sweet fire,” “fire that does not burn,” and even “fire of the lamp” since it really has an enlightening effect on the images.[22] [24]

Although in contexts such as this one here at Counter-Currents, I’ve been calling attention to how Traditional the method is, Horowitz is right to emphasize how profoundly American it is. Deriving in the first instance from Emerson, it is indeed, as Horowitz says, “applied Transcendentalism.”

In fact, it is clearly a manifestation of what Camille Paglia has called “The North American [Literary] Tradition.” Paglia argues that the confrontation of Romanticism with North American Protestantism “achieved a new fusion of ideas – a sensory pragmatism or engagement with concrete experience, rooted in the body, and at the same time a visionary celebration of artistic metaspace – that is, the fictive realm of art, fantasy and belief projected by great poetry and prefiguring our own cyberspace.”[23] [25]

This uniquely American “synthesis of the pragmatic and the visionary,” from Emerson to James, continues, I would say, in Neville’s method, which crucially combines both physical relaxation (the body) and visionary intensity (mind and will); [24] [26] conversely, Horowitz notes that most New Age practitioners of “the law of attraction,” “the Secret,” and so on fail because they seem to think they can rely on thought and wishing alone.

We saw how Horowitz disparages the “ersatz Hinduism” derived from socially stagnant societies, and Paglia notes that American democracy and capitalism “enhanced individualism and promoted social mobility.” So at first glance it may seem somewhat ironic that he devotes two chapters to Neville, born in Barbados, and James Allen (author of the New Thought classic As a Man Thinketh), an Englishman. Yet their stories are almost archetypically American.

Neville, like so many before him, emigrated from Barbados to New York to make his fortune.[25] [27] Though the Great Depression caused his Broadway career to flame out, his career as a “metaphysical lecturer” led to a certain amount of prosperity (to judge from his teaching stories, he and his small family seem to have lived one of those Nick and Nora Charles lifestyles, moving from one swanky hotel or apartment house to another), while his extended clan in Barbados used the same methods to expand a grocery store into the food services conglomerate Goddard Enterprises, still the largest multinational headquartered in the Caribbean. [26] [28]

It was James Allen’s father who emigrated to New York, but with less success, being murdered and robbed two days after arrival; as a result, young Allen had to leave school to support the family. He married, lived quietly, produced more than one book a year, and died from tuberculosis at the age of forty-seven.

Allen’s story is compelling not because he became rich – he didn’t, monetarily, at least – but for the way it brings together Horowitz’s other themes of power, self-effort, and testing by experience.

The noblest aspects of human nature emerge when the individual is striving toward something. When the thing striven for is attained, however, such as a comfortable and prosperous old age, the human mind often redirects its attention onto the smallest and most fleeting details of quotidian life.

James Allen, by contrast, was compelled to struggle most of his life. But that struggle never deformed him. The decisive factor in his life . . . was that he saw life’s upward hill not as a path toward comfort but toward refinement.

One is reminded of Colin Wilson’s frequent observation, that those born well-off tend to develop a lazy and pessimistic view of life, while those who need to constantly struggle acquire an optimistic attitude; positive thinking, indeed. Allen’s wife’s description of her husband also reminds us of Wilson’s concept of existential philosophizing;

One is reminded of Colin Wilson’s frequent observation, that those born well-off tend to develop a lazy and pessimistic view of life, while those who need to constantly struggle acquire an optimistic attitude; positive thinking, indeed. Allen’s wife’s description of her husband also reminds us of Wilson’s concept of existential philosophizing;

He never wrote theories, or for the sake of writing; but he wrote when he had a message, and it became a message only when he had lived it out in his own life, and knew that it was good. Thus he wrote facts, which he had proven by practice.

As I said above, Horowitz devotes much attention to critiquing the intellectually stagnant, naïve, and, sometimes, dishonest forms of New Thought today, as well as the unfair attacks of the sciencey folks; he also marshals fascinating evidence that mainstream, not even “cutting edge,” science provides ways to understand how and why New Thought – Neville’s method in particular – works.

Most quantum physicists wouldn’t be caught dead/alive as Schrodinger’s cat dealing with the theories of Neville. But there is an elegant intersection of possibility between his theology and the quantum theorizing of Schrodinger and Everett.

Everett’s concept of multiple worlds and outcomes could be the key to why thoughts are causative, or, put differently, why reality bends to the vantage point of the observer.

It’s not so much that our thinking and perspective make things happen, but that we choose from among things that already exist in potential – like the superposition of a particle in a wave state.

If thoughts register data, then a shift in the use of the sensory tool of thought – like a physicist deciding whether to take a measurement and the perspective from which it is taken – determines or alters what data is experienced. Based upon how your thoughts and feeling states are used, they expose you to different, and coexisting, phenomena.

Neville argued that everything you see and experience, including others, is the product of your own individual dream of reality. Through a combination of emotional conviction and mental images, he taught, you imagine your world into being – and all people and events are rooted in you, as you are ultimately rooted in God, or an Over-Mind. When you awaken to your true self, Neville argued, you will know yourself to be a slumbering branch of the Creator clothed in human form and at the helm of infinite possibilities. We all have this experience within our own dreams of reality.

As noted in my review [29] of one of Horowitz’s previous books,[27] [30] I find this sort of thing intriguing, but not necessarily entirely compelling – and Horowitz doesn’t insist he has all the right answers, anyway; as always, your mileage may vary.[28] [31]

New to me, and more intriguing, are examples he draws from biology and medicine: he concludes that “we are living through a period of new findings in placebo research, ranging from placebo surgeries to myriad studies liking positive expectancy to a strengthened immunological response, as well as widely accepted findings in the nascent field of neuroplasticity, in which redirected thoughts are seen to alter brain biology.”

Perhaps more important are his attempts to tease out some consistency and plausibility in the claims of New Thought practitioners and what passes for theorists among them.

One of his most important contributions is emphasizing one reason why it doesn’t always appear to work: most New Thinkers not only seem content to just vaguely hope for the best, they also seem to believe that thought is the only power at work.

If I posit a connection between the individual and some kind of higher capacity of the mind, that does not mean that only “one thing” – a law of mentation – is going on in your life. Lots of events, whether biological, mechanical, or metaphysical, can be simultaneously occurring. We live under many laws and forces, of which the impact of the mind is one.

The law of gravity is ever operative, but it is mitigated by other laws, such as mass. The experience of gravity radically differs on the moon, Earth, and Jupiter. So it is with the mind: surrounding events and realities matter.[29] [32]

I would suggest – and hope to develop in a future essay – that even if, as Neville insists, we are “all imagination,” and that imagination is God, that there are levels of power or accomplishment here as with other cosmic forces or natural talents;[30] [33] it may be possible to train one’s imagination, as an athlete or dancer (like Neville, remember) trains their body, to attain greater mastery, but there are limits. As Horowitz says:

Contrary to many purveyors of spiritual self-help, I reject the notion that we can become anything we dream of. Not all desires are realistic. . . . Your age, training, and education matter – as do geography, finances, and time. These are not to be seen as barriers – but they are serious considerations.

“There are surprises,” he adds – as he says elsewhere, there have been notably short basketball stars – but don’t bet on it.[31] [34]

Understanding the hand you’ve been dealt is all part of the preliminary step of finding one’s true aim; and this in itself may be the most valuable part of the practice of positive thought:

Positive-mind philosophy places a demand on us, one that we may think we’ve risen to but have never really tried. And that is: To come to an understanding of precisely what we want. When we organize our thoughts in a certain way – with a fearless maturity and honesty – we may be surprised to discover our true desires.

The need to recognize that we work within cosmic limits is complementary to Horowitz’s ethical meditations. All this talk of Rand and Nietzsche might make some readers (though not many on this site, perhaps) a little uneasy. And isn’t actually existing New Thought a part of the whole “Social Gospel” wing of Progressivism?

Is there a dichotomy between Neville’s radical individualism and the communal vision of [for example, early twentieth-century socialist and New Thought guru Wallace D.] Wattles? Not for me. . . . Not only do opposites attract, but paradoxes complete.

Neville’s vision of individual excellence, and Wattles’ ideal of community enrichment are inextricably bound because New Thought – unlike secular Objectivism and varying forms of ceremonial magick or Thelemic philosophy – functions along the lines of Scriptural ethics. New Thought . . . promulgates a radically karmic ethos, in which the thoughts and actions enacted toward others simultaneously play out toward the self; doing unto others is doing unto self – the part and the whole are inseparable.

Must a seeker choose between a nice car and “awareness”? Must I choose between Wallace D. Wattles and Neville? Both were bold, beautiful, and right in many ways; both had a vision of ultimate freedom – of the creative individual determining rather than bending to circumstance.

If Horowitz sees Neville as not that different from free-marketeer Rand or socialist Wattles, perhaps that’s because he hearkens back to an earlier kind of Progressive thought, also part of Paglia’s North American tradition rather than the Frankfurt School of pessimistic European thinkers she deplores. This kind of Leftism preached action (Reform! Progress!) rather than passive nursing of grievances and demands for special privileges and reparations; the Left that used to sing “Don’t mourn, organize [35]!” rather than “Born this way [36].”

This contrast is manifested here in a blistering, several-page critique of modern Progressive Barbara Ehernreich’s critique of positive thinking, which “stems from laziness of research . . . willful neglect of facts for the sake of scoring a witty point,” and a shallow, entirely secondhand approach to its intellectual history.[32] [37]

Her sloppiness stems from her elitism, which he contrasts with her former co-chair of the Democratic Socialists of American, Michael Harrington (who died in 1989):

You cannot love a country in any authentic sense when you offhandedly disparage – and make no effort to take full measure of – an outlook embraced by varied millions of Americans, of all backgrounds and classes.[33] [38]

In my review of Horowitz’s edition of Neville’s At Your Command, I noted that it appeared at a synchronous moment – Election Day – and provided a useful guide to understanding Trump’s meme mastery as the key to his victory.[34] [39] I’ve argued that Positive Thinking ultimately gave America Trump. If the Left actually want to avoid another Trump, they will need to engage in the kind of self-analysis Horowitz advises here – what do they, or rather the voters, really want? – and move back to Harrington’s kind of working-class solidarity. As Spencer J. Quinn has argued on this site [40]:

Carlson sees a civil war on the horizon and argues that the Left and Left-leaning members of the Right are the ones who are primarily responsible. They are also the reason why we got Donald Trump in 2016. If the Left wishes to not have populist nationalists like Trump in the White House, then they’d better clean up their acts and start catering to the needs of the majority.[35] [41]

Just as Horowitz’s edition of At Your Command arrived on Election Day, so Horowitz’s latest comes at a propitious time, just as the Dissident Right has created a new meme, the NPC. “Offhandedly disparage” does indeed suggest the literally mindless sloganeering of the Left’s minions.[36] [42] Horowitz’s discussion would lead us to think it is hardly confined to the Left, however; it is a result of eschewing the supposedly lazy and self-indulgent world of Positive Thinking for the “hard-headed” philosophy of materialism.

But as Horowitz shows, it is Positive Thinking – Blake’s “mental strife” – that requires work, while as Kathleen Raine said of Blake’s war against Locke and Newton:

The Big Brother of materialist philosophy must of necessity become a tyrant because he compels humanity (in Yeats’ words) to become passive before a mechanized nature.[37] [43]

Identity politics is pure passivity: their constituents want benefits. It is only “dreamers” like Neville or Horowitz who want to work.[38] [44]

With all this talk of integrity and right action, it’s no surprise that Horowitz eventually gets around to offering some life coaching, which, given the reversal of causality postulated by quantum mechanics,[39] [45] he presents as advice for the past you. It bears being quoted in extenso, since it’s pretty good in itself, and also seems like the sort of thing our own Jef Costello, or even Jack Donovan, but probably not Jordan Peterson, might offer as well:

Immediately disassociate from destructive people and forces, if not physically then ethically – and watch for the moment when you can do so physically.

Use every means to improve your mental acuity. Every sacrifice of empty leisure or escapism for study, industry, and growth is a fee paid to personal freedom.

Train the body. Grow physically strong. Reduce consumption. You will be strengthened throughout your being.

Seek no one’s approval through humor, servility, or theatrics. Be alone if necessary. But do not compromise with low company.

At the earliest possible point, learn meditation (i.e., Transcendental Meditation), yoga, and martial arts (select good teachers).

Go your own way – literally. Walk/bike and don’t ride the bus or in a car, except when necessary. Do so in all weather: rain, snow, etc. Be independent physically and you will be independent in other ways.

Learn-study-rehearse. Pursue excellence. Or else leave something alone. Go to the limit in something or do not approach it.

Starve yourself of the compulsion to derive your sense of wellbeing from your perception of what others think of you. Do this as an alcoholic avoids a drink or an addict a needle. It will be agonizing at first, since you may have no other perception of self; but this, finally, is the sole means of experiencing Self.

At the end, he issues a challenge to the presumably now buff and fully intellectually-prepped reader: a specific practice that will allow you to join your will to his and whoever else has the courage to take it up. As we’ve seen throughout, from the title on, there are echoes of Evola here; for the aim of UR and KRUR was also the creation of such “magical chains.”[40] [46]

There are some arguable points in Horowitz’s exploration of Positive Thinking, and even some missteps. As an example of the latter, several pages devoted to Senator Cory Booker as an exemplar of positive thought will likely produce a different impression after his buffoonish performance at the recent Kavanaugh hearings, as well as more recent allegations [47]; perhaps he exemplifies Horowitz’s sound advice about taking an honest inventory of your strengths and limits before formulating a goal.

On the other hand, Jef Costello will be pleased to find Jonathan Frid’s landing the role of Barnabas Collins on Dark Shadows adduced as an example of perseverance in pursuit of one’s true goal.

Horowitz also distances himself from many New Thought figures by demurring from the idea that the human imagination is God, tout court; he finds room for a personal God, and even insists on the efficacy of icons, medallions, and so forth. Horowitz even goes so far as to endorse William James’ notion of a deity created or supported by our prayers. One recalls how Jason Jorjani handles the same material – parapsychology and the gods – with the suggestion that these so-called “gods” are higher, but not necessarily “divine,” powers, or even extraterrestrials, ruthlessly exploiting us.[41] [48]

By contrast, Neville, for example, always insisted that “God is your own wonderful human imagination,” and heaped scorn on those who not only worship an external deity, but focus their attentions on “little medals and statues.”

Here again, Evola has preceded us; Evola, in fact, explains the differences between the “dry” and “wet” paths by considering their use of images. The pupil first constructs an image of his ideal Self, concentrating all his thoughts and will on it. In the wet path, the duality remains, the Self is worshipped from afar; while in the dry path, one attempts to gradually achieve unity, to become the Self.[42] [49]

Perhaps most importantly, one might also ask whether the example of quantum superposition (in layman’s terms, the observer determining the observed), adduced to explain the possibility of “changing the future,” as Neville would say, contradicts or makes questionable the value of Horowitz’s participant/observer model?

In the end, how are we to evaluate Horowitz’s project? Positive Thinking turns out to be not at all like the airy-fairy, feel-good notions peddled by Oprah and Co.[43] [50] It’s about the hard work of analyzing your own self to find out what it is you truly want, the honesty of admitting what that deepest desire is (power, money, success, fame, glamour), and the integrity and commitment to concentrate on it to the exclusion of anything else.

Going back to my reference to Colin Wilson’s notion of existential philosophy – that is, a philosophy developed and tested in one’s real life – we can add something Kathleen Raine said about Blake, Neville’s favorite writer (other than the author of the Bible):

He understood that ideas, like passions, cannot otherwise exist than in men; and for Blake the final test of any philosophy is the kind of human beings it produces.[44] [51]

So take the challenge, join the Miracle Club, and see what you can make of yourself – and thus, what you can make of your world. It might even be, as David Lynch suggests on the cover, “solid gold.”[45] [52]

Notes

[1] [53] Frank Costello, The Departed [54] (Martin Scorsese, 2006).

[2] [55] Mitch Horowitz, One Simple Idea: How Positive Thinking Reshaped Modern Life (New York: Crown, 2014).

[3] [56] What appears to be a linked series of quotations from the back cover of a collection of his lectures entitled Be What You Wish (Floyd, Va.: Sublime Books, 2015).

[4] [57] These essays, published variously in Aristokratia and on Counter-Currents, are now collected in Magick for Housewives: Essays on Alt-Gurus [58] (Melbourne, Victoria: Manticore, 2018).

[5] [59] Which is not to say that important contributions haven’t come from furriners, such as Emile Coué (remembered for his mantra, “Every day, in every way, I’m getting better and better”) and the Englishmen James Allen (to whom Horowitz devotes a chapter) and Arnold Bennett.

[6] [60] Even Adlai Stevenson got into the act. When running for president in 1956, Peale said that Stevenson was unfit because he was divorced; Stevenson famously quipped, “I find Saint Paul appealing and Saint Peale appalling.” In 1960, Peale called Kennedy unfit, as a Catholic, and Stevenson responded thus: “America was not built by wishful thinking. It was built by realists, and it will not be saved by guess work and self-deception. It will only be saved by hard work and facing the facts.” Says the guy who lost. Twice. See the section on “Peale and Stevenson” on Wikipedia [61].

[7] [62] For example, Ramzpaul, here [63].

[8] [64] Did positive thinking help elect Trump? See my Kindle single, Trump: The Art of the Meme [65] (Amazon, 2016).

[9] [66] One might compare the situation of institutions and disciplines dominated by the PC mentality – bereft of any need to actually defend their ideas, the academic Left has intellectually degenerated to a point where its ideas are preposterous, and its spokesmen incapable of mounting a defense, anyway.

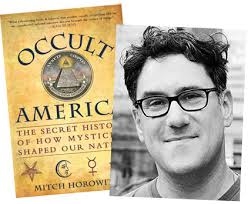

[10] [67] “Mitch Horowitz is a PEN Award-winning historian, longtime publishing executive, and a leading New Thought commentator with bylines in The New York Times, Time, Politico, Salon, and The Wall Street Journal and media appearances on Dateline NBC, CBS Sunday Morning, All Things Considered, and Coast to Coast AM. He is the author of several books, including Occult America and One Simple Idea. He lives in New York City.”—Publisher’s note.

[11] [68] Reprinted in three volumes several decades later; the first volume has been translated as Introduction to Magic: Rituals and Practical Techniques for the Magus (Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions, 2001), and the second volume is due out next year. Inner Traditions also happens to publish The Miracle Club.

[12] [69] The Path of Cinnabar: An Intellectual Autobiography; translated by Sergio Knipe (London: Artkos Media, 2009), p. 107.

[13] [70] “I want to strike at the blithe, sometimes childish tone that pervades much of its culture. . . . Services at many New Thought-oriented churches are a cross between pep rallies and preschool birthday parties, with attendant exhortations from the pulpit: ‘Isn’t this the most fun ever?’” Camille Paglia describes “New Age” as “all-accepting and undemanding, suspending guilt and judgement. It offers a psychology without conflict and a subjective ethics without challenge or moral responsibility.” See “The Mighty River of Classics: Tradition and Innovation in Modern Education,” reprinted in Provocations: Collected Essays (New York: Pantheon, 2018).

[14] [71] “It is truly strange that proof is demanded concerning the possibility of a kind of knowledge instead of searching for it and verifying it for one’s self by undertaking the work necessary for its acquisition. For those who possess this knowledge, what interest can there be in all this discussion? Substituting a ‘theory of knowledge’ for knowledge itself is perhaps the greatest admission of impotence in modern philosophy.” “Oriental Metaphysics [72],” from Tomorrow, Vol. 12, No. 1. (Winter 1964) (the journal later continued as Studies in Comparative Religion).

[15] [73] Unless, of course, the Ancient Astronaut theorists are right about vimanas [74].

[16] [75] See Collin Cleary, “What is Odinism?, Part III: The Odinic & the Faustian [76],” and Ricardo Duchesne, “Oswald Spengler & the Faustian Soul of the West [77].”

[17] [78] See Julius Evola, The Doctrine of Awakening: The Attainment of Self-Mastery According to the Earliest Buddhist Texts (London: Luzac & Co., 1951; Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions, 1995) and Julius Evola, The Yoga of Power: Tantra, Shakti, and the Secret Way, trans. Guido Stucco (Rochester, Vt. Inner Traditions, 1992); as well as his “Spiritual Virility in Buddhism [79]” and “What Tantrism Means to Modern Western Civilization [80],” included in Julius Evola, East and West [81] (San Francisco: Counter-Currents Publishing, 2018).

[18] [82] As we’ll see, this is not just an offhand remark; both Neville and quantum mechanics postulate a four-dimensional, serial universe in which the future is determined only by the choice of the observer in the present.

[19] [83] For example, Horowitz notes the importance of the New Thought principle, that you tend to become what you think about, dwell on, hate, or envy; we might compare this to the classic scene where Toohey asks Roark, “What do you think of me?” and Roark replies, “But I don’t think of you.”

[20] [84] “God’s a champ,” as Dr. Hannibal Lecter says, adding that, “It feels good because God has power. If one does what God does enough times, one will become as God is” (Red Dragon, aka Manhunter). Conversely, it doesn’t work for “manifesting” trivial desires, or parlor tricks to satisfy skeptics, like King Herod: “Prove to me that you’re no fool / Walk across my swimming pool” (Jesus Christ Superstar). As Alan Watts said, the Westerner thinks that if you say, I am God, then you should be able to “prove it” by doing random, meaningless things like make lightning strike. But if you are God, what you want to do is exactly what’s happening now all around yourself and within yourself; you’ve simply chosen to get out of your own way.

[21] [85] No expectations, because, as Neville would say, you assume that what you wish for already exists; he calls this “thinking from the end.”

[22] [86] “Commentary on the Opus Magicum,” in Evola, Introduction to Magic , op. cit., p. 57. Dr. Lechter’s protégé, The Tooth Fairy, a kind of perverted New Thinker, comes to mind: an investigator, Buffalo Bill, muses over one of his tell-tale moths, “Somebody grew this guy. Fed him honey and nightshade, kept him warm. Somebody loved him.” Silence of the Lambs (Jonathan Demme, 1990).

[23] [87] “The North American intellectual tradition [88]; Paglia: To hell with European philosophers: The breakthroughs of non-European thinkers are the 1960s’ greatest legacy,” Salon.com, March 4, 2000; reprinted in Provocations: Collected Essays.

[24] [89] Paglia cites the “exploration of the body [which] inspired the revolutionary choreography of Isadora Duncan and Martha Graham” [see “Isadora Duncan: Pagan Priestess of Dance [90]”] and “the Stanislavskian ‘Method’ of Lee Strasberg’s Actors Studio” as examples of “the primacy of the body in the North American intellectual tradition.” Neville was initially both a dancer and an actor on Broadway, and although Duncan would likely have hated his act, Horowitz and others believe his physical training suggested, and added, his ability to attain states of deep relaxation. Horowitz also explicitly mentions “method” acting as an analogy to Neville’s own “method.”

[25] [91] On the basis of the same itinerary, today’s SJWs claim Alexander Hamilton as an immigrant of color and the hero of the hip-hip hit Hamilton [92]; in realty, of course, he was not only white but an elitist. Neville’s “English background and elegant bearing” might lead one to think him another toff, but Horowitz notes that Neville, unlike the historic Hamilton, thought that “privilege did not belong to the rich but to the truly imaginative,” in the manner of Jefferson’s natural aristocracy (thought the latter certainly opposed unlimited immigration [92]). In one of his visions, Neville heard the words, “Down with the blue bloods!”

[26] [93] Drafted in late 1942, Neville used his methods to obtain an honorable discharge by early 1943, so as to perform “necessary war-related work” – metaphysical lectures in Greenwich Village – as well as automatic American citizenship. Horowitz has done considerable legwork to verify such stories.

[27] [94] “Lord Kek Commands: A Look at the Origins of Meme Magic [29],” now reprinted in Magick for Housewives, op. cit.; see also Trump: The Art of the Meme, op. cit.

[28] [95] For an equally recent book-length treatment, see Dean Radin’s Real Magic: Ancient Wisdom, Modern Science, and a Guide to the Secret Power of the Universe (New York: Harmony, 2018); Radin figures in a couple of Horowitz’s anecdotes.

[29] [96] “The bird attained whatever grace its shape possesses not as a result of the mere desire for flight, but because it had to fly in air, against gravitation.” T. E. Hulme, quoted by Colin Wilson in The Age of Defeat (1959; London: Aristea Press, 2018). Though no friend of what he calls “magical thinking,” the ZMan makes a similar point [97] when he attributes the fanaticism of the Left to the loss of the “leash” or “governor” of Christianity, which put limits on the zeal with which one could pursue heavenly perfection.

[30] [98] As Jesus says, in one of Neville’s favorite quotes, “I and the Father are one; yet the Father is greater than me.” Kathleen Raine says that for Blake (Neville’s favorite source outside the Bible), “All spaces and places are in reality created by the one universal imagination which in every individual being varies the ratio at will.” Kathleen Raine, Blake and the New Age (New York: Routledge, 2011), p. 172.

[31] [99] Despite the medical evidence of efficacy of what Horowitz calls “hopeful expectancy,” he calls this a “complement” to recognized medical treatment; if a belief deters you from seeking treatment, it is not a hope, but “a delusion.” He also firmly condemns New Thought theorists and practitioners who, when their methods fail, try to save their theories by “blaming the victim” for lack of faith.

[32] [100] “How can the leading critic of positive-mind mechanics evidently not have read . . . the very philosopher who made the movement possible to begin with? If a freshman quoted Emerson from secondary sources in a term paper I’d have questions for that student.”

[33] [101] Ehrenreich’s elitist disdain is of a piece with Obama’s “bitter clingers to God and guns,” Hillary’s disparagement of half the electorate as “a basket of deplorables,” the general media attitude to positive-thinking Trump, and indeed just about any media treatment of the Dissident Right. “Progressive politics is now [1995!] too often merely empty rhetoric, divorced from the everyday life of the people for whom liberals claim to speak.” Camille Paglia, “Language and the Left,” The Advocate, March 7, 1995; reprinted in Provocations, op. cit.

[34] [102] “Lord Kek Commands: A Look at the Origins of Meme Magic [29].”

[35] [103] Spencer J. Quinn, “Tucker Carlson’s Ship of Fools [40].”

[36] [104] In Herman Wouk’s The Caine Mutiny (New York: Dell, 1951), Lieutenant Keefer calls Captain Queeg “a Freudian playground,” mentioning his manner of conversing “in second phrases and slogans: ‘I kid you not’.”

[37] [105] Op. cit., pp. 157-158. Jason Jorjani gives a similar analysis of eighteenth-century materialism, arguing that De Sade can be understood as articulating the logical result of the “claustrophobia of the Cartesian ego” trapped in a mechanical universe; see his Prometheus and Atlas (London: Arktos Media, 2016), Introduction, loc. 189-196 (quote at loc. 2201).

[38] [106] “Who the hell is in charge? A bunch of accountants trying to make a dollar into a dollar ten? I want to work. I want to build something of my own. How do you not understand that? You did it yourself forty years ago.” Don Draper to Bert Cooper, Mad Men S03E13, “Shut the Door, Have a Seat.”

[39] [107] “This chap is called Feynman, Richard Feynman, Professor Feynman at Cal. Tech. He is considered one of the world’s greatest physicists. . . . He wrote a paper which came out in 1949. It was printed in what is known as The Science Newsletter and he was describing the behavior of a little particle which is produced by atomic disintegration. It is named today by our scientists as the positron. He wrote of the positron that ‘it starts from where it hasn’t been and speeds to where it was but an instant ago; arriving there it is bounced so hard its time sense is reversed, and it returns to where it hasn’t been.’” Neville, “On the Law [108],” February 19, 1965.

[40] [109] “[There] is an interesting and enigmatic account in the last chapter of the third volume [of Magic, still untranslated] entitled ‘”La Grande Orma”: la scena e le quinte’ (The ‘Great Trail’: The Stage and the Wings), signed by a mysterious ‘Ekatlos.’ In it the author strives to point out the traces of a long-perpetuated, ancient initiatic chain in the very bosom of the land around Rome, and its attempt, however futile, to exert a rectifying influence within the sphere of the Fascist movement during the first years in which it took power. In regard to this, Evola himself wrote that the aim of the ‘chain’ of the UR Group, aside from ‘awakening a higher force that might serve to help the singular work of every individual,’ was also to act ‘on the type of psychic body that begged for creation, and by evocation to connect it with a genuine influence from above,’ so that ‘one may perhaps have the possibility of working behind the scenes in order to ultimately exert an effect on the prevailing forces in the general environment.’ Although this attempt did not meet with its hoped-for success . . .” Introduction to Magic, op. cit., Preface by Retano Del Ponte. For a critique by The Archdruid, and my response, see “Battle of the Magicians: Baron Evola between the Dancer & the Druid [110],” reprinted in Magick for Housewives, op. cit.

[41] [111] Jorjani, op. cit.

[42] [112] “You must generate – first by imagining and then by realizing it – a superior principle confronting everything you usually are (e.g., an instinctive life, thoughts, feelings) [This is the bondage of experiences]. This principle must be able to control, contemplate, and measure what you are, in a clear knowledge, moment by moment. There will be two of you: yourself standing before ‘the other.’ All in all, the work consists of a ‘reversal’: you have to turn the ‘other’ into ‘me’ and the ‘me’ into ‘the other.’

“Then, in contrast to the mystical, or Christian, path, where the Other remains Other, and the Self remains in the feminine position of need and desire . . . In the magical, dry, or solar way, you will create a duality in your being not in an unconscious and passive manner (as the mystic does), but consciously and willingly; you will shift directly on the higher part and identify yourself with that superior and subsistent principle, whereas the mystic tends to identify with his lower part, in a relationship of need and of abandonment.

“Slowly but gradually, you will strengthen this ‘other’ (which is yourself) and create for it a supremacy, until it knows how to dominate all the powers of the natural part and master them totally. Then, the entire being, ready and compliant, reaffirms itself, digests and lets itself be digested, leaving nothing behind.” Julius Evola, Introduction to Magic, op. cit., pp. 88-91. The process of lovingly “cultivating” the Other as part of the process of initiation is referenced in The Silence of the Lambs, by the aforementioned Buffalo Bill. I consider this process of imaginal magic in the context of two Hollywood films in my essay “Of Costner, Corpses, and Conception: Mother’s Day Meditations on The Untouchables and The Big Chill,” here [113] and reprinted in my collection The Homo and the Negro [114] (San Francisco: Counter-Currents Publishing, 2012; 2nd, Embiggened Edition, 2017).

[43] [115] One “expert” interviewed for Rhonda Byrne’s Oprah-approved video The Secret [116] says that one day, checks just started arriving in the mail, golly gee!

[44] [117] Kathleen Raine, op. cit., p. 156.

[45] [118] Lynch also says: “Dear Twitter Friends, Please check out my interview with Mitch Horowitz on @RadioInterfaith [119].” Or take a look at the transcript here [120]. We learn that “every morning since 1973, he has gotten up. . . closed his eyes . . . slowed down his breathing . . . and ‘gone fishing’ in the ocean he calls the ‘unified field,’ using Transcendental Meditation.”

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg