D. H. Lawrence on Men & Women

Derek HAWTHORNE

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

1. Love and Strife

In a 1913 letter D. H. Lawrence writes that “it is the problem of to-day, the establishment of a new relation, or the readjustment of the old one, between men and women.” Lawrence’s views about relations between the sexes, and about sex differences are perhaps his most controversial – and they have frequently been misrepresented. But before we delve into those views, let us ask why it should be the case that establishing a new relation between men and women is “the problem of to-day.” The reason is fairly obvious. The species divides itself into male and female, reproduces itself thereby, and the overwhelming majority of human beings seek their fulfillment in a relationship to the opposite sex. If relations between the sexes have somehow been crippled—as Lawrence believes they have been—then this is a catastrophe. It is hard to imagine a greater, more pressing problem.

In a 1913 letter D. H. Lawrence writes that “it is the problem of to-day, the establishment of a new relation, or the readjustment of the old one, between men and women.” Lawrence’s views about relations between the sexes, and about sex differences are perhaps his most controversial – and they have frequently been misrepresented. But before we delve into those views, let us ask why it should be the case that establishing a new relation between men and women is “the problem of to-day.” The reason is fairly obvious. The species divides itself into male and female, reproduces itself thereby, and the overwhelming majority of human beings seek their fulfillment in a relationship to the opposite sex. If relations between the sexes have somehow been crippled—as Lawrence believes they have been—then this is a catastrophe. It is hard to imagine a greater, more pressing problem.

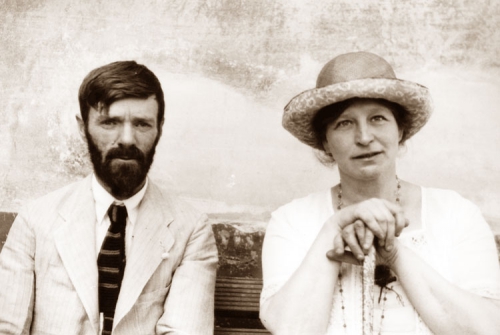

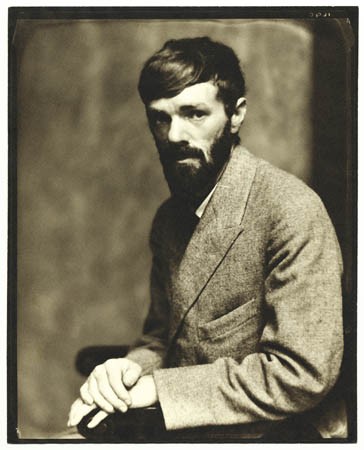

Lawrence came to relations with women bearing serious doubts about his own manhood, and with the conviction that his nature was fundamentally androgynous. Throughout his life, but especially as a boy, it was easier for him to relate to women and to form close bonds with them. Thus, when Lawrence discusses the nature of woman he draws not only upon his experiences with women, but also upon his understanding of his own nature. One of the questions we must examine is whether, in doing so, Lawrence was led astray. After all, Lawrence eventually came to repudiate the idea of any sort of fundamental androgyny and to claim that men and women are radically different. In Fantasia of the Unconscious he writes, “We are all wrong when we say there is no vital difference between the sexes.” Lawrence wrote this in 1921 intending it to be provocative, but it is surely much more controversial in today’s world, where it has become a dogma in some circles to insist that sex differences (now called “gender differences”) are “socially constructed.” Lawrence continues: “There is every difference. Every bit, every cell in a boy is male, every cell is female in a woman, and must remain so. Women can never feel or know as men do. And in the reverse, men can never feel and know, dynamically, as women do.”

Lawrence saw relations between the sexes as essentially a war. He tells us in his essay “Love” that all love between men and women is “dual, a love which is the motion of melting, fusing together into oneness, and a love which is the intense, frictional, and sensual gratification of being burnt down, burnt into separate clarity of being, unthinkable otherness and separateness.” The love between men and women is a fusing—or a will to fusing—but one that never fully takes place because the relation is also fundamentally frictional. Again and again Lawrence emphasizes the idea that men and women are metaphysically different. In other words, they have different, and even opposed ways of being in the world. They are not just anatomically different; they have different ways of thinking and feeling, and achieve satisfaction and fulfillment in life through different means.

Lawrence’s view of the difference between the sexes can be fruitfully compared to the Chinese theory of yin and yang. These concepts are of great antiquity, but the way in which they are generally understood today is the product of an ambitious intellectual synthesis that took place under the early Han dynasty (207 B.C.–9 A.D.). According to this philosophy, the universe is shot through with an ultimate principle or power known as the Tao. However, the Tao divides itself into two opposing principles, yin and yang. These oppose yet complement each other. Yang manifests itself in maleness, hardness, harshness, dominance, heat, light, and the sun, amongst other things. Yin manifests itself in femaleness, softness, gentleness, yielding, cold, darkness, the moon, etc.

Contrary to the impression these lists might give, however, yang is not regarded as “superior” to yin; hardness is not superior to softness, nor is dominance superior to yielding. Each requires the other and cannot exist without the other. In certain situations a yang approach or condition is to be preferred, in others a yin approach. On occasion, yang may predominate to the point where it becomes harmful, and it must be counterbalanced by yin, or vice versa. (These principles are of central importance, for example, in traditional Chinese medicine.) The Tao Te Ching, a work written by a man chiefly for men extols the virtues of yin, and continually advises one to choose yin ways over yang. Lao-Tzu tells us over and over that it is “best to be like water,” that “those who control, fail. Those who grasp, lose,” and that “soft and weak overcome stiff and strong.”

Like the Taoists, Lawrence regards maleness and femaleness as opposed, yet complementary. It is not the case that the male, or the male way of being, is superior to the female, or vice versa. In a sense the sexes are equal, yet equality does not mean sameness. The error of male chauvinism is in thinking that one way, the male way, is superior; that dominance and hardness are just “obviously” superior to their opposites.

Yet the same error is committed by some who call themselves feminists. Tacitly, they assume that the male or yang characteristics are superior, and enjoin women to seek fulfillment in life through cultivating those traits in themselves. To those who might wonder whether such a program is possible, to say nothing of desirable, the theory of the “social construction of gender” is today being offered as support. According to this view, the only inherent differences between men and women are anatomical, and all of the intellectual, emotional, and behavioral characteristics attributed to the sexes throughout history have actually been the product of culture and environment. (And so “yin and yang,” according to this view, is really a rather naïve philosophy which confuses nurture with nature.) Clearly, Lawrence would reject this theory. In doing so, he is on very solid ground.

It would, of course, be foolish not to recognize that some “masculine” and “feminine” traits are culturally conditioned. An obvious example would be the prevailing view in American culture that a truly “masculine” man is unable, without the help of women or gay men, to color-coordinate his wardrobe. However, when one sees certain traits in men and women displaying themselves consistently in all cultures and throughout all of human history it makes sense to speak of masculine and feminine natures. It is plausible to argue that a trait is culturally conditioned only if it shows up in some cultures but not in others. Unfortunately, the “social construction of gender” thesis has achieved the status of a dogma in academic circles. And, in truth, ultimately it has to be asserted as dogma since believing in it requires that we ignore the evidence of human history, profound philosophies such as Taoism, and most of the scientific research into sex differences that has taken place over the last one hundred years.

I said earlier that Lawrence believes men and women to be “metaphysically different,” and in his essay “A Study of Thomas Hardy” he does indeed write as if he believes they actually see the world with a different metaphysics in mind:

It were a male conception to see God with a manifold Being, even though He be One God. For man is ever keenly aware of the multiplicity of things, and their diversity. But woman, issuing from the other end of infinity, coming forth as the flesh, manifest in sensation, is obsessed by the oneness of things, the One Being, undifferentiated. Man, on the other hand, coming forth as the desire to single out one thing from another, to reduce each thing to its intrinsic self by process of elimination, cannot but be possessed by the infinite diversity and contrariety in life, by a passionate sense of isolation, and a poignant yearning to be at one.

So, men seek or are preoccupied with multiplicity, and women with unity. What are we to make of such a bizarre claim? First of all, it seems to run counter to the Greek tradition, especially that of the Pythagoreans, which tended to identify the One with the masculine, and the Many with the feminine. However, if one looks to Empedocles, a pre-Socratic philosopher Lawrence was particularly keen on, one finds a different story. Empedocles posits two fundamental forces which are responsible for all change in the universe: Love and Strife. Love, at the purely physical level, is a force of attraction. It draws things together, and without the intervention of Strife it would result in a monistic universe in which only one being existed. Strife breaks up and divides. It is a force of repulsion and separation. Now, Empedocles seems to identify Love with Aphrodite, and we may infer, though he does not say so, that Strife is Ares. In other words, he identifies his two forces with the archetypal female and male. This can offer us a clue as to what Lawrence is up to.

In Lawrence’s view, it is the female who wants to draw things, especially people, together. It is the female who yearns to heal divisions, to break down barriers. “Coming forth as the flesh, manifest in sensation” she seeks to overcome separateness through feeling, primarily through love. In the family situation, it is the female who tries to unite and overcome discord through love, whereas it is the male, typically, who frustrates this through the insistence on rules and distinctions. The ideal of universal love and an end to strife and division is fundamentally feminine—one which men, throughout history, have continually frustrated. It is characteristic of men to make war, and characteristic of women, no matter what cause or principle is involved, to object and to call for peace and unity.

Now the male, as Lawrence puts it, suffers from a sense of isolation, and a “yearning to be one.” He yearns for oneness, in fact, as the male yearns for the female. Yet his entire being disposes him to see the world in terms of its distinctness, and, indeed, to make a world rife with distinctions. Lawrence implies that polytheism is a “male” religion, and monotheism a “female” one. It is easy to see the logic involved in this. Polytheism sees the divine being that permeates the world as many because the world is itself many. Further, societies with polytheistic religions have always been keenly aware of ethnic and social differences, differences within the society (as in the Indian caste system), and between societies. Monotheism, on the other hand, tends toward universalism. Christianity especially, however it has actually been practiced, declares all men equal in the sight of God and calls for peace and unity in the world. (Lawrence, as we shall see later on, does indeed regard Christianity as a “feminine” religion, and blames it, in part, for feminizing Western men.)

This fundamental, metaphysical difference has the consequence that men and women do, in a real sense, live in different worlds. But perhaps such a formulation reflects a male bias towards differentiation. It is equally correct to say, in a more “feminine” formulation, that it is the same world seen in two, complementary ways. Indeed, it may be the case that it is difficult to see, from a male perspective, how the two sexes and their different ways of thinking and perceiving can achieve a rapprochement. Lawrence believes, of course, that they can live together, and that their opposite tendencies can be harmonized. In this way he is like Heraclitus, Lawrence’s favorite pre-Socratic, when he says “what is opposed brings together; the finest harmony is composed of things at variance, and everything comes to be in accordance with strife.” Heraclitus also tells us that “They do not understand how, though at variance with itself, it [the Logos] agrees with itself. It is a backwards-turning attunement like that of the bow and lyre.” In order to make a lyre or a bow, the two opposite ends of a piece of wood must be bent towards each other, never meeting, but held in tension. Their tension and opposition makes possible beautiful music, in the case of the lyre, and the propulsion of an arrow, in the case of the bow. Both involve a harmony through opposition.

In a 1923 newspaper interview Lawrence is quoted as saying “If men were left to themselves, they would rush off . . . into destruction. But women keep life back at its own center. They pull the men back. Women have enormous passive strength, the strength of inertia.” Here Lawrence uses an image he was very fond of: women are at the center, the hub. This is because they are closer to “the source” than men are.

In Fantasia of the Unconscious, Lawrence tells us “The blood-consciousness and the blood-passion is the very source and origin of us. Not that we can stay at the source. Nor even make a goal of the source, as Freud does. The business of living is to travel away from the source. But you must start every single day fresh from the source. You must rise every day afresh out of the dark sea of the blood.” Lawrence believes that men yearn for purposive, creative activity, which involves moving away from the source. However, the energy and inspiration for purposive activity is drawn from the source, and so there is a complementary movement back towards it.

In Fantasia of the Unconscious, Lawrence tells us “The blood-consciousness and the blood-passion is the very source and origin of us. Not that we can stay at the source. Nor even make a goal of the source, as Freud does. The business of living is to travel away from the source. But you must start every single day fresh from the source. You must rise every day afresh out of the dark sea of the blood.” Lawrence believes that men yearn for purposive, creative activity, which involves moving away from the source. However, the energy and inspiration for purposive activity is drawn from the source, and so there is a complementary movement back towards it.

In The Rainbow, Lawrence describes how Tom Brangwen, besotted with his wife, seems to lose himself in a sensual obsession with her, and with knowing her sexually. But gradually,

Brangwen began to find himself free to attend to the outside life as well. His intimate life was so violently active, that it set another man in him free. And this new man turned with interest to public life, to see what part he could take in it. This would give him scope for new activity, activity of a kind for which he was now created and released. He wanted to be unanimous with the whole of purposive mankind.

Sex is one means of contacting the source. Men contact the source through women. This does not mean, of course, that blood-consciousness is in women but not in men. Rather, it means that in most men the blood-consciousness in them is “activated” primarily through their relationship to women. Second, in women blood-consciousness is more dominant than it is in men. Women are more intuitive than men; they operate more on the basis of feeling than intellect. It should not be necessary to point out that whereas such an observation might, in another author, be taken as a denigration of women, in Lawrence it is actually high praise. Women are also much more in tune with their bodies and bodily cycles than men are. Men tend to see their bodies as adversaries that must be whipped into shape.

When Lawrence continually tells us that we must find a way to reawaken the blood-consciousness in us, he is writing primarily for men. Women are already there—or, at least, they can get there with less effort. There is an old adage: “Women are, but men must become.” To be feminine is a constant state that a woman has as her birthright. Masculinity, on the other hand, is something men must achieve and prove. Rousseau in Emile states “The male is male only at certain moments, the female is female all of her life, or at least all her youth.” We exhort boys to “be a man,” but never does one hear girls told to “be a woman.” One can compliment a man simply by saying “he’s a man,” whereas “she’s a woman” seems mere statement of fact. The psychological difference between masculinity and femininity mirrors the biological fact that all fetuses begin as female; something must happen to them in order to make them male. It also articulates what is behind the strange conviction many men have had, including many great poets and artists, that woman is somehow the keeper of life’s mysteries; the one closest to the well-spring of nature.

In “A Study of Thomas Hardy,” Lawrence states that “in a man’s life, the female is the swivel and centre on which he turns closely, producing his movement.” Goethe tells us “Das ewig Weiblich zieht uns hinan” (“The Eternal Feminine draws us onwards”). The female, the male’s source of the source, stands at the center of his life. The woman as personification of the life mystery entices him to come together with her, and through their coupling the life mystery perpetuates itself. But he is not, ultimately, satisfied by this coupling. He goes forth into the world, his body renewed by his contact with the woman, but full of desire to know this mystery more adequately, and to be its vehicle through creative expression.

Without a woman, a man feels unmoored and ungrounded, for without a woman he has no center in his life. A man—a heterosexual man—can never feel fulfilled and can never reach his full potential without a woman to whom he can turn. As to homosexual men, it is a well-known fact that many cultivate in themselves characteristics that have been traditionally usually associated with woman: refined taste in clothing and decoration, cooking, gardening, etc. What these characteristics have in common is connectedness to the pleasures of the moment, and to the rhythms and necessities of life. Men are normally purpose-driven and future-oriented. They tend to overlook those aspects of life that please, but lack any greater purpose other than pleasing. They tend, therefore, to be somewhat insensitive to their surroundings, to color, to texture, to odor, to taste. They tend, in short, to be so focused upon doing, that they miss out on being. Heterosexual men look to women to ground them, and to provide these ingredients to life—ingredients which, in truth, make life livable. Homosexual men must make a woman within themselves, in order to be grounded. (This does not mean, however, that they must become effeminate – see my review essay of Jack Donovan’s Androphilia for more details.)

Homosexual men are, of course, the exception not the rule. Lawrence writes, of the typical man, “Let a man walk alone on the face of the earth, and he feels himself like a loose speck blown at random. Let him have a woman to whom he belongs, and he will feel as though he had a wall to back up against; even though the woman be mentally a fool.” And what of the woman? What does she desire? Lawrence tells us that “the vital desire of every woman is that she shall be clasped as axle to the hub of the man, that his motion shall portray her motionlessness, convey her static being into movement, complete and radiating out into infinity, starting from her stable eternality, and reaching eternity again, after having covered the whole of time.” Man is the “doer,” the actor, whereas woman need do nothing. Just by being woman she becomes the center of a man’s universe.

The dark side of this, in Lawrence’s view, is a tendency in women towards possessiveness, and towards wanting to make themselves not just the center of a man’s life but his sole concern. In Women in Love, Lawrence’s describes at length Rupert Birkin’s process of wrestling with this aspect of femininity:

But it seemed to him, woman was always so horrible and clutching, she had such a lust for possession, a greed of self-importance in love. She wanted to have, to own, to control, to be dominant. Everything must be referred back to her, to Woman, the Great Mother of everything, out of whom proceeded everything and to whom everything must finally be rendered up.

Birkin sees these qualities in Ursula, with whom he is in love. “She too was the awful, arrogant queen of life, as if she were a queen bee on whom all the rest depended.” He feels she wants, in a way, to worship him, but “to worship him as a woman worships her own infant, with a worship of perfect possession.”

Woman’s possessiveness is understandable given that the man is necessary to her well-being: she is only happy if she is center to the orbit and activity of some man. Again, for Lawrence, such a claim does not denigrate women, for he has already as much as said that a man is nothing without a woman. Nevertheless, some will see in this view of men and woman a sexism that places the man above the woman. From Lawrence’s perspective, this is illusory. It is true that the man is “doer,” but his perpetual need to act and to do stands in stark contrast to the woman, who need do nothing in order be who she is. It is true, further, that men’s ambition has given them power in the world, but it is a power that is nothing compared to that of the woman, who exercises her power without having to do anything. She reigns, without ruling. The man does what he does, but must return to the woman, and is “like a loose speck blown at random without her” – and he knows this. Much of misogyny may have to do with this. From the man’s perspective, the woman is all-powerful, and the source of her power a mystery.

Many modern feminists, however, conceive of power in an entirely male way, as the active power of doing. Lawrence recognized that in trying to cultivate this male power within themselves, women do not rise in the estimation of most men. Instead they are diminished, for men’s respect for and fascination with women springs entirely from the fact that unlike themselves women do not have to chase after an ideal of who they ought to be; they do not have to get caught up in the rat race in order to respect themselves. They can simply be; they can live, and take joy just in living.

One can make a rough distinction between two types of feminism. The most familiar type is what one might call the “woman on the street feminism,” which one encounters from average, working women, and which they imbibe from television, films, and magazines. This feminism essentially has as its aim claiming for women all that which formerly had been the province of men—including not only traditionally male jobs, but even male ways of speaking, moving, dressing, bonding, exercising, and displaying sexual interest. Ironically, this form of feminism is at root a form of masculinism, which makes traditionally masculine traits the hallmarks of the “liberated” or self-actualized human being.

The other type of feminism is usually to be found only in academia, though not all academic feminists subscribe to it. It insists that women have their own ways of thinking, feeling, and relating to others. Feminist philosophers have written of woman’s “ways of knowing” as distinct from men’s, and have even put forward the idea that women approach ethical decision-making in a markedly different way. It is this form of feminism to which Lawrence is closest. Lawrence’s writings are concerned with liberating both men and women from the tyranny of a modern civilization which cuts them off from their true natures. Liberation for modern women cannot mean becoming like modern men, for modern men are living in a condition of spiritual (as well as wage) slavery. In an essay on feminism, Wendell Berry writes

It is easy enough to see why women came to object to the role of [the comic strip character] Blondie, a mostly decorative custodian of a degraded, consumptive modern household, preoccupied with clothes, shopping, gossip, and outwitting her husband. But are we to assume that one may fittingly cease to be Blondie by becoming Dagwood? Is the life of a corporate underling—even acknowledging that corporate underlings are well paid—an acceptable end to our quest for human dignity and worth? . . . How, I am asking, can women improve themselves by submitting to the same specialization, degradation, trivialization, and tyrannization of work that men have submitted to? [Wendell Berry, “Feminism, the Body, and the Machine,” in The Art of the Commonplace: The Agrarian Essays of Wendell Berry, ed. Norman Wirzba (Washington, D.C.: Counterpoint, 2002), 69–70.]

I will return to this issue later.

Having now characterized, in broad strokes, Lawrence’s views on the differences between men and woman, I now turn to a more detailed discussion of each.

2. The Nature of Man

As we have seen, Lawrence believes that men (most men) need to have a woman in their lives. Their relationship to a woman serves to ground their lives, and to provide the man not only with a respite from the woes of the world, but with energy and inspiration. However, this is not the same thing as saying that the man makes the woman, or his relationship to her, the purpose of his life. In Fantasia of the Unconscious Lawrence writes, “When he makes the sexual consummation the supreme consummation, even in his secret soul, he falls into the beginnings of despair. When he makes woman, or the woman and child, the great centre of life and of life-significance, he falls into the beginnings of despair.” This is because Lawrence believes that true satisfaction for men can come only from some form of creative, purposive activity outside the family.

Having a woman is therefore a necessary but not a sufficient condition for male happiness. In addition to a woman, he must have a purpose. Women, on the other hand, do not require a purpose beyond the home and the family in order to be happy. This is another of those claims that will rankle some, so let us consider two important points about what Lawrence has said. First, he is speaking of what he believes the typical woman is like, just as he is speaking of the typical man. There are at least a few exceptions to just about every generalization. Second, we must ask an absolutely crucial question of those who regard such claims as demeaning women: why is being occupied with home and family lesser than having a purpose (e.g., a career) outside the home? The argument could be made—and I think Lawrence would be sympathetic to this—that the traditional female role of making a home and raising children is just as important and possibly more important than the male activities pursued outside the home. Again, much of contemporary feminism sees things from a typically male point of view, and denigrates women who choose motherhood rather than one of the many meaningless, ulcer-producing careers that have long been the province of men.

Having a woman is therefore a necessary but not a sufficient condition for male happiness. In addition to a woman, he must have a purpose. Women, on the other hand, do not require a purpose beyond the home and the family in order to be happy. This is another of those claims that will rankle some, so let us consider two important points about what Lawrence has said. First, he is speaking of what he believes the typical woman is like, just as he is speaking of the typical man. There are at least a few exceptions to just about every generalization. Second, we must ask an absolutely crucial question of those who regard such claims as demeaning women: why is being occupied with home and family lesser than having a purpose (e.g., a career) outside the home? The argument could be made—and I think Lawrence would be sympathetic to this—that the traditional female role of making a home and raising children is just as important and possibly more important than the male activities pursued outside the home. Again, much of contemporary feminism sees things from a typically male point of view, and denigrates women who choose motherhood rather than one of the many meaningless, ulcer-producing careers that have long been the province of men.

Lawrence writes, “Primarily and supremely man is always the pioneer of life, adventuring onward into the unknown, alone with his own temerarious, dauntless soul. Woman for him exists only in the twilight, by the camp fire, when day has departed. Evening and the night are hers.” Lawrence’s male bias creeps in here a bit, as he romanticizes the “dauntless” male soul. Men and women always believe, in their heart of hearts, that their ways are superior. Nevertheless, Lawrence is not here relegating women to an inferior position. Half of life is spent in the evening and night. Day belongs to the man, night to the woman. It is a division of labor. Lawrence is drawing here, as he frequently does, on traditional mythological themes: the man is solar, the woman lunar.

Lawrence characterizes the man’s pioneering activity as follows: “It is the desire of the human male to build a world: not ‘to build a world for you, dear’; but to build up out of his own self and his own belief and his own effort something wonderful. Not merely something useful. Something wonderful.” In other words, the man’s primary purpose is not having or doing any of the “practical” things that a wife and a family require. And when he acts on a larger scale—Lawrence gives building the Panama Canal as an example—it is not with the end in mind of making a world in which wives and babes can be more comfortable and secure (“a world for you, dear”). He seeks to make his mark on the world; to bring something glorious into existence. And so men create culture: games, religions, rituals, dances, artworks, poetry, music, and philosophy. Wars are fought, ultimately, for the same reason. It is probably true, as is often asserted, that every war has some kind of economic motivation. However, it is probably also true to assert that in the case of just about every actual war there was another, more cost-effective alternative. Men make war for the same reason they climb mountains, jump out of airplanes, race cars, and run with the bulls: for the challenge, and the fame and glory and exhilaration that goes with meeting the challenge. It is an aspect of male psychology that most women find baffling, and even contemptible.

Now, curiously, Lawrence refers to this “impractical,” purposive motive of the male as an “essentially religious or creative motive.” What can he mean by this? Specifically, why does he characterize it as a religious motive?

It is religious because it involves the pursuit of something that is beyond the ordinary and the familiar. It is a leap into the unknown. The man has to follow what Lawrence frequently calls the “Holy Ghost” within himself and to try to make something within the world. He yearns always for the yet-to-be, the yet-to-be-realized, and always has his eye on the future, on what is in process of coming to be. Yet there seems to be, at least on the surface, a strange inconsistency in Lawrence’s characterization of the man’s motive as religious. After all, for Lawrence the life mystery, the source of being is religious object—and women are closer to this source. Man is entranced by woman, and with her he helps to propagate this power in the world through sex, but his sense of “purpose” causes him to move away from the source. So why isn’t it the woman whose “motives” are religious, and the man who is, in effect, irreligious?

The answer is that religion is not being at the source: it is directedness toward the source. Religion is possible only because of a lack or an absence in the human soul. Religion is ultimately a desire to put oneself at-one with the source. But this is possible only if one is not, originally or most of the time, at one with it. In a way, the woman is not fundamentally religious because she is the goddess, the source herself. The sexual longing of the man for the woman, and his utter inability ever to fully satisfy his desire and to resolve the mystery that is woman, are a kind of small-scale allegory for man’s large-scale, religious relationship to the source of being itself. He is, as I have said, renewed by his relations with women and, for a time, satisfied. But then he goes forth into the world with a desire for something, something. He creates, and when he does he is acting to exalt the life mystery (religion and art), to understand it (philosophy and science), or to further it (invention and production).

Lawrence speaks of how a man must put his wife “under the spell of his fulfilled decision.” Woman, who rules over the night, draws man to her and they become one through sex. Man, who rules the day, draws woman into his purpose, his aim in life, and through this they become one in another fashion. The man’s purpose does not become the woman’s purpose. He pursues this alone. But if the woman simply believes in him and what he aims to do, she becomes a tremendous source of support for the man, and she gives herself a reason for being. The man needs the woman as center, as hub of his life, and the woman needs to play this role for some man. Without a mate, though a man may set all sorts of purposes before him, ultimately they seem meaningless. He feels a sense of hollow emptiness, and drifts into despair. He lets his appearance go, and lives in squalor. He may become an alcoholic and a misogynist. He dies much sooner than his married friends, often by his own hand. As to the woman, without a man who has set himself some purpose that she can believe in, she assumes the male role and tries to find fulfillment through some kind of busy activity in the world. But as she pursues this, she feels increasingly bitter and hard, and a terrific rage begins to seethe beneath her placid surface. She becomes a troublemaker and a prude. Increasingly angry at men, she makes a virtue of necessity and declares herself emancipated from them. She collects pets.

In Studies in Classic American Literature Lawrence writes:

As a matter of fact, unless a woman is held, by man, safe within the bounds of belief, she becomes inevitably a destructive force. She can’t help herself. A woman is almost always vulnerable to pity. She can’t bear to see anything physically hurt. But let a woman loose from the bounds and restraints of man’s fierce belief, in his gods and in himself, and she becomes a gentle devil.

If a woman is to be the hub in the life a man, and derive satisfaction from that, everything depends on the spirit of the man. A few lines later in the same text Lawrence states, “Unless a man believes in himself and his gods, genuinely: unless he fiercely obeys his own Holy Ghost; his woman will destroy him. Woman is the nemesis of doubting man.” In order for the woman to believe in a man, the man must believe in himself and his purpose. If he is filled with self-doubt, the woman will doubt him. If he lacks the strength to command himself, he cannot command her respect and devotion. And the trouble with modern men is that they are filled with self-doubt and lack the courage of their convictions.

Lawrence, following Nietzsche, in part blames Christianity for weakening modern, Western men. Men are potent—sexually and otherwise—to the extent they are in tune with the life force. But Christianity has “spiritualized” men. It has filled their heads with hatred of the body, and of strength, instinct, and vitality. It has infected them with what Lawrence calls the “love ideal,” which demands, counter to every natural impulse, that men love everyone and regard everyone as their equal.

Frequently in his fiction Lawrence depicts relationships in which the woman has turned against the man because he is, in effect, spiritually emasculated. The most dramatic and symbolically obvious example of this is the relationship of Clifford and Connie in Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Clifford returns from the First World War paralyzed from the waist down. But like the malady of the Grail King in Wolfram’s Parzival, this is only (literarily speaking) an outward, physical expression of an inward, psychic emasculation. Clifford is far too sensible a man to allow himself to be overcome by any great passion, so the loss of his sexual powers is not so dear. He has a keen, cynical wit and believes that he has seen through passion and found it not as great a thing as poets say that it is. It is his spiritual condition that drives Connie away from him, not so much his physical one. And so she wanders into the game preserve on their estate (representing the small space of “wildness” that still can rise up within civilization) and into the arms of Mellors, the gamekeeper. Their subsequent relationship becomes a hot, corporeal refutation of Clifford’s philosophy.

In Women in Love, Gerald Crich, the industrial magnate, is destroyed by Gudrun essentially because he does not believe in himself. Outwardly, he is “the God of the machine.” But his mastery of the material world is meaningless busywork, and he knows it. Gudrun is drawn to him because of this outward appearance of power, but when she finds that it is an illusion she hates him, and ultimately drives him to his death. For Lawrence, this is an allegory of the modern relationship between the sexes. Men today are masters of the material universe as they have never been before, but inside they are anxious and empty. The reason is that these “materialists” are profoundly afraid of and hostile to matter and nature, especially their own. Their intellect and “will to power” has cut them off from the life force and they are, in their deepest selves, impotent. The women know this, and scorn them.

In The Rainbow, Winifred Inger is Ursula’s teacher (with whom she has a brief affair), and an early feminist. She tells Ursula at one point,

The men will do no more,–they have lost the capacity for doing. . . . They fuss and talk, but they are really inane. They make everything fit into an old, inert idea. Love is a dead idea to them. They don’t come to one and love one, they come to an idea, and they say “You are my idea,” so they embrace themselves. As if I were any man’s idea! As if I exist because a man has an idea of me! As if I will be betrayed by him, lend him my body as an instrument for his idea, to be a mere apparatus of his dead theory. But they are too fussy to be able to act; they are all impotent, they can’t take a woman. They come to their own idea every time, and take that. They are like serpents trying to swallow themselves because they are hungry.”

In Fantasia of the Unconscious Lawrence writes, “If man will never accept his own ultimate being, his final aloneness, and his last responsibility for life, then he must expect woman to dash from disaster to disaster, rootless and uncontrolled.”

It is important to understand here that the issue is not one of power. Lawrence’s point not that men must dominate or control their wives. In fact, in a late essay entitled “Matriarchy” (originally published as “If Women Were Supreme”) Lawrence actually advocates rule by women, at least in the home, because he believes it would liberate men. He assumes the truth of the claim—now in disrepute—that early man had lived in matriarchal societies and writes, “the men seem to have been lively sorts, hunting and dancing and fighting, while the woman did the drudgery and minded the brats. . . . A woman deserves to possess her own children and have them called by her name. As to the household furniture and the bit of money in the bank, it seems naturally hers.” The man, in such a situation, is not the slave of the woman because the man is “first and foremost an active, religious member of the tribe.” The man’s real life is not in the household, but in creative activity, and religious activity:

The real life of the man is not spent in his own little home, daddy in the bosom of the family, wheeling the perambulator on Sundays. His life is passed mainly in the khiva, the great underground religious meeting-house where only the males assemble, where the sacred practices of the tribe are carried on; then also he is away hunting, or performing the sacred rites on the mountains, or he works in the fields.

Men, Lawrence tells us, have social and religious needs which can only be satisfied apart from women. The disaster of modern marriage is that men not only think they have to rule the roost, but they accept the woman’s insistence that he have no needs or desires that cannot be satisfied through his relationship to her. He becomes master of his household, and slave to it at the same time:

Now [man’s] activity is all of the domestic order and all his thought goes to proving that nothing matters except that birth shall continue and woman shall rock in the nest of this globe like a bird who covers her eggs in some tall tree. Man is the fetcher, the carrier, the sacrifice, and the reborn of woman. . . . Instead of being assertive and rather insentient, he becomes wavering and sensitive. He begins to have as many feelings—nay, more than a woman. His heroism is all in altruistic endurance. He worships pity and tenderness and weakness, even in himself. In short, he takes on very largely the original role of woman.

Ironically, in accepting such a situation without a fight, he only earns the woman’s contempt: “Almost invariably a [modern] married woman, as she passes the age of thirty, conceives a dislike, or a contempt, of her husband, or a pity which is near to contempt. Particularly if he is a good husband, a true modern.”

3. The Nature of Woman

In Fantasia of the Unconscious Lawrence writes, “Women will never understand the depth of the spirit of purpose in man, his deeper spirit. And man will never understand the sacredness of feeling to woman. Each will play at the other’s game, but they will remain apart.” But what is meant by “feeling” here? Lawrence is referring again to his belief that women live, to a greater extent than men, from the primal self. In the case of most men today, “mind-consciousness” and reason are dominant—to the point where they are frequently detached from “blood-consciousness” and feeling.

In describing the nature of woman Lawrence once again draws on perennial symbols: “Woman is really polarized downwards, towards the centre of the earth. Her deep positivity is in the downward flow, the moon-pull.” The sun represents man, and the moon woman. Day belongs to him, and night to her. However, another set of mythic images associates the earth with woman and the sky with man. The “pull” in women is towards the earth, and this means several things. First, the earth is the source of chthonic powers, and so, as poetic metaphor, it represents the primal, pre-mental, animal aspect in human beings. In a literal sense, however, Lawrence believes that women are more in tune than men with chthonic powers: with the rhythms of nature and the cycle of seasons. Further, the “downward flow” refers to Lawrence’s belief that the lower “centres” of the body are, in a sense, more primitive, more instinctual than the upper, and that women tend to live and act from these centers more than men do. Lawrence writes, “Her deepest consciousness is in the loins and belly. . . . The great flow of female consciousness is downwards, down to the weight of the loins and round the circuit of the feet.”

Finally, to be “polarized downwards, towards the centre of the earth” means to have one’s life, one’s vital being fixed in reference to a central point. If Lawrence intends us to assume that man is polarized upwards then we may ask, toward what? If woman is oriented towards the center of the earth, then–following the logic of the mythic categories–is man oriented toward the center of the sky? But the sky has no center. Man is less fixed than woman; he is a wanderer. He is a hunter, a seeker, a pioneer, an adventurer. Woman, on the other hand, lives from the axis of the world. Mircea Eliade writes that “the religious man sought to live as near as possible to the Center of the World.” Woman is at the center. Man begins there, then goes off. He returns again and again, the phallic power in him rising in response to the chthonic power of the woman. And his religious response is an ongoing effort to bring his daytime self into line with the life force he experiences when in the arms of the woman.

Woman, Lawrence tells us, “is a flow, a river of life,” and this flow is fundamentally different from the man’s river. However, “The woman is like an idol, or a marionette, always forced to play one role or another: sweetheart, mistress, wife, mother.” The mind of the male is built to analyze and categorize. But the nature of woman, like the nature of nature itself, defies categorization. Even before Bacon, man’s response to nature was to force it to yield up its secrets, to bend it to the human will, or to see it only within the narrow parameters of whatever theory was fashionable at the moment. The male mind attempts to do this to woman as well–and the woman, to a great extent, cooperates. She fits herself into the roles expected of her by authority figures, whether it is dutiful daughter-sister-wife-mother, or dutiful feminist and career-woman.

Lawrence writes, “The real trouble about women is that they must always go on trying to adapt themselves to men’s theories of women, as they always have done.” Two opposing wills exist in women, Lawrence believes: a will to conform or to submit, and a will to reject all boundaries and be free. In Women in Love, Birkin compares women to horses:

“And of course,” he said to Gerald, “horses haven’t got a complete will, like human beings. A horse has no one will. Every horse, strictly, has two wills. With one will, it wants to put itself in the human power completely—and with the other, it wants to be free, wild. The two wills sometimes lock—you know that, if ever you’ve felt a horse bolt, while you’ve been driving it. . . . And woman is the same as horses: two wills act in opposition inside her. With one will, she wants to subject herself utterly. With the other she wants to bolt, and pitch her rider to perdition.”

Ursula, who is present at this exchange, laughs and responds “Then I’m a bolter.” The trouble is that she is not.

Lawrence’s fiction is filled with vivid portrayals of women (arguably much more vivid and well-drawn than his portrayals of men). The central characters in several of his novels are women (The Rainbow, The Lost Girl, The Plumed Serpent, and Lady Chatterley’s Lover). All of Lawrence’s major female characters exhibit these two wills, but frequently he presents pairs of women each of whom represents one of the wills. This is the case in Women in Love. Ultimately, in Ursula’s character the will to surrender emerges as dominant. In her sister Gudrun the will to be free and wild dominates, with tragic results. In Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Connie Chatterley exhibits the will to surrender, and her sister Hilda the will to be free. The two lesbians in Lawrence’s novella The Fox are cut from the same cloth. Similar pairs of women also crop up in Lawrence’s short stories. In each case, one woman learns the joys of submitting, not to a man but to the earth, to nature, to the life mystery within her. The man is a means to this, however. The best example of this in Lawrence’s fiction is probably Connie Chatterley’s journey to awakening. In John Thomas and Lady Jane, an earlier version of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Lawrence has Connie speak of the significance of her lover and of his penis: “I know it was the penis which really put the evening stars into my inside self. I used to look at the evening star, and think how lovely and wonderful it was. But now it’s in me as well as outside me, and I need hardly look at it. I am it. I don’t care what you say, it was penis gave it me.” As to the other woman in Lawrence’s fiction, she tends to be horrified by the primal self in her, and its call to surrender. She lives from the ego. She rages against anything in her nature that is unchosen, and against anything else that would hem her in, especially any man. She views herself as “realistic” and hardheaded, but the general impression she gives is of being hardhearted and sterile.

In his portrayals of the latter type of woman, Lawrence is partly depicting what he believes to be a perennial aspect of the female character, and partly depicting what he regards as the quintessential “modern” woman. It is in the nature of woman to counterbalance the will to submit with an opposing will that “bolts,” and kicks against all that which limits her, including her own nature. Lawrence believes that modern womanhood and all the problems of women today arise from the over-development of that will to freedom.

A “will to freedom” sounds like a good thing, so it is important to realize that essentially what Lawrence means by this is a negative will which tries either to control, or to destroy all that which it cannot control. Lawrence’s critique of modernity is a major topic in itself, but suffice it say that he believes that in the modern period a disavowal of the primal self takes place on a mass, cultural scale. The seeds of this disavowal were sown by Christianity, and reaped by modern scientism, which becomes the avowed enemy of the religion that helped foster it. Individuals live their lives from the standpoint of ego and mental-consciousness, and distrust the blood-consciousness. The negative will in women seizes upon reason and ego-dominance as a means to free herself from the influence of her dark, chthonic self, and from the influence of the men that this dark, chthonic self draws her to. The will to negate, using the mind as its tool, thus becomes the path to “liberation.”

Lawrence writes in Apocalypse:

Today, the best part of womanhood is wrapped tight and tense in the folds of the Logos, she is bodiless, abstract, and driven by a self-determination terrible to behold. A strange ‘spiritual’ creature is woman today, driven on and on by the evil demon of the old Logos, never for a moment allowed to escape and be herself.

And in an essay he writes, “Woman is truly less free today than ever she has been since time began, in the womanly sense of freedom.” This is, of course, exactly the opposite of what is asserted by most pundits today, when they speak of the progress made by woman in the modern era. Why does Lawrence believe that woman is now so unfree? The answer is implied in the quotation from Apocalypse: she is not allowed to be herself.

In Studies in Classic American Literature Lawrence tells us

Men are not free when they are doing just what they like. The moment you can do just what you like, there is nothing you care about doing. Men are only free when they are doing what the deepest self likes.

And there is getting down to the deepest self! It takes some diving.

Because the deepest self is way down, and the conscious self is an obstinate monkey. But of one thing we may be sure. If one wants to be free, one has to give up the illusion of doing what one likes, and seek what IT wishes done.

What Lawrence says here is applicable to both men and women. “To be oneself” in the true sense means to answer to the call of the deepest self. We can only achieve our “fullness of being” if we do so. The mind invents all manner of goals and projects and ideals to be pursued, but ultimately all that we do produces only frustration and emptiness if we act in a way that does not fundamentally satisfy the needs of our deepest, pre-mental, bodily nature.

What Lawrence says here is applicable to both men and women. “To be oneself” in the true sense means to answer to the call of the deepest self. We can only achieve our “fullness of being” if we do so. The mind invents all manner of goals and projects and ideals to be pursued, but ultimately all that we do produces only frustration and emptiness if we act in a way that does not fundamentally satisfy the needs of our deepest, pre-mental, bodily nature.

Lawrence writes further in Apocalypse: “The evil Logos says she must be ‘significant,’ she must ‘make something worth while’ of her life. So on and on she goes, making something worth while, piling up the evil forms of our civilization higher and higher, and never for a second escaping to be wrapped in the brilliant fluid folds of the new green dragon.” Earlier in the same text, Lawrence tells us that “The long green dragon with which we are so familiar on Chinese things is the dragon in his good aspect of life-bringer, life-giver, life-maker, vivifier.” In short, the “green dragon” represents the life force, the source of all, the Pan power. Lawrence is saying that modern woman, in search of something “significant” to do with her life, falls in with all the corrupt (largely, money-driven) pursuits that have brought men nothing but ulcers, emptiness, and early death. “All our present life-forms are evil,” he writes. “But with a persistence that would be angelic if it were not devilish woman insists on the best in life, by which she means the best of our evil life-forms, unable to realize that the best of evil life-forms are the most evil.” Like men, she loses touch with the natural both within herself and in the world surrounding her. Lawrence’s dragon symbolizes both of these: primal nature as such, and the primal nature within me. It is this dragon which Lawrence seeks to awake in himself, and in his readers. The tragedy of modern woman is that she has renounced the dragon, whereas she would be better off being devoured by it.

In John Thomas and Lady Jane Lawrence also links the ideal of fulfilled womanhood to the dragon. Following Connie Chatterley’s musings on the meaning of the phallus (which I quoted earlier), Lawrence writes:

The only thing which had taken her quite away from fear, if only for a night, was the strange gallant phallus looking round in its odd bright godhead, and now the arm of flesh around her, the socket of the hand against her breast, the slow, sleeping thud of the man’s heart against her body. It was all one thing—the mysterious phallic godhead. Now she knew that the worst had happened. This dragon had enfolded her, and its folds were pure gentleness and safety.

For Lawrence capitalism destroyed the soul and the mystery of life, as did democracy and equality. He devoted most of his life to finding a new-yet-old religion that will return the mystery to life and reconnect humanity to the cosmos.

For Lawrence capitalism destroyed the soul and the mystery of life, as did democracy and equality. He devoted most of his life to finding a new-yet-old religion that will return the mystery to life and reconnect humanity to the cosmos. I have contributed several essays to Counter-Currents dealing with

I have contributed several essays to Counter-Currents dealing with  It is Lawrence’s

It is Lawrence’s

The Futurists were contemptuous of all tradition, of all that is past:

The Futurists were contemptuous of all tradition, of all that is past:

1. The Genealogy of Modernity

1. The Genealogy of Modernity Lawrence encountered the effects of modernity—especially the Industrial Revolution—directly in his native Midlands. He saw how if affected people, generally for the worse. Again and again he sets his stories against the backdrop of the collieries. He saw the miners become increasingly dehumanized. Working in the earth, they become cut off from it and from themselves. They lived, but they did not flourish. Lawrence’s remarks about the Industrial Revolution, capitalism, and the condition of the miners put him quite close to the thought of Marx and other socialist writers. In fact, it would not be at all unreasonable to claim Lawrence as a kind of socialist. However, as we shall see, few socialists would wish to do so!

Lawrence encountered the effects of modernity—especially the Industrial Revolution—directly in his native Midlands. He saw how if affected people, generally for the worse. Again and again he sets his stories against the backdrop of the collieries. He saw the miners become increasingly dehumanized. Working in the earth, they become cut off from it and from themselves. They lived, but they did not flourish. Lawrence’s remarks about the Industrial Revolution, capitalism, and the condition of the miners put him quite close to the thought of Marx and other socialist writers. In fact, it would not be at all unreasonable to claim Lawrence as a kind of socialist. However, as we shall see, few socialists would wish to do so! In a 1913 letter D. H. Lawrence writes that “it is the problem of to-day, the establishment of a new relation, or the readjustment of the old one, between men and women.” Lawrence’s views about relations between the sexes, and about sex differences are perhaps his most controversial – and they have frequently been misrepresented. But before we delve into those views, let us ask why it should be the case that establishing a new relation between men and women is “the problem of to-day.” The reason is fairly obvious. The species divides itself into male and female, reproduces itself thereby, and the overwhelming majority of human beings seek their fulfillment in a relationship to the opposite sex. If relations between the sexes have somehow been crippled—as Lawrence believes they have been—then this is a catastrophe. It is hard to imagine a greater, more pressing problem.

In a 1913 letter D. H. Lawrence writes that “it is the problem of to-day, the establishment of a new relation, or the readjustment of the old one, between men and women.” Lawrence’s views about relations between the sexes, and about sex differences are perhaps his most controversial – and they have frequently been misrepresented. But before we delve into those views, let us ask why it should be the case that establishing a new relation between men and women is “the problem of to-day.” The reason is fairly obvious. The species divides itself into male and female, reproduces itself thereby, and the overwhelming majority of human beings seek their fulfillment in a relationship to the opposite sex. If relations between the sexes have somehow been crippled—as Lawrence believes they have been—then this is a catastrophe. It is hard to imagine a greater, more pressing problem. In Fantasia of the Unconscious, Lawrence tells us “The blood-consciousness and the blood-passion is the very source and origin of us. Not that we can stay at the source. Nor even make a goal of the source, as Freud does. The business of living is to travel away from the source. But you must start every single day fresh from the source. You must rise every day afresh out of the dark sea of the blood.” Lawrence believes that men yearn for purposive, creative activity, which involves moving away from the source. However, the energy and inspiration for purposive activity is drawn from the source, and so there is a complementary movement back towards it.

In Fantasia of the Unconscious, Lawrence tells us “The blood-consciousness and the blood-passion is the very source and origin of us. Not that we can stay at the source. Nor even make a goal of the source, as Freud does. The business of living is to travel away from the source. But you must start every single day fresh from the source. You must rise every day afresh out of the dark sea of the blood.” Lawrence believes that men yearn for purposive, creative activity, which involves moving away from the source. However, the energy and inspiration for purposive activity is drawn from the source, and so there is a complementary movement back towards it. Having a woman is therefore a necessary but not a sufficient condition for male happiness. In addition to a woman, he must have a purpose. Women, on the other hand, do not require a purpose beyond the home and the family in order to be happy. This is another of those claims that will rankle some, so let us consider two important points about what Lawrence has said. First, he is speaking of what he believes the typical woman is like, just as he is speaking of the typical man. There are at least a few exceptions to just about every generalization. Second, we must ask an absolutely crucial question of those who regard such claims as demeaning women: why is being occupied with home and family lesser than having a purpose (e.g., a career) outside the home? The argument could be made—and I think Lawrence would be sympathetic to this—that the traditional female role of making a home and raising children is just as important and possibly more important than the male activities pursued outside the home. Again, much of contemporary feminism sees things from a typically male point of view, and denigrates women who choose motherhood rather than one of the many meaningless, ulcer-producing careers that have long been the province of men.

Having a woman is therefore a necessary but not a sufficient condition for male happiness. In addition to a woman, he must have a purpose. Women, on the other hand, do not require a purpose beyond the home and the family in order to be happy. This is another of those claims that will rankle some, so let us consider two important points about what Lawrence has said. First, he is speaking of what he believes the typical woman is like, just as he is speaking of the typical man. There are at least a few exceptions to just about every generalization. Second, we must ask an absolutely crucial question of those who regard such claims as demeaning women: why is being occupied with home and family lesser than having a purpose (e.g., a career) outside the home? The argument could be made—and I think Lawrence would be sympathetic to this—that the traditional female role of making a home and raising children is just as important and possibly more important than the male activities pursued outside the home. Again, much of contemporary feminism sees things from a typically male point of view, and denigrates women who choose motherhood rather than one of the many meaningless, ulcer-producing careers that have long been the province of men. What Lawrence says here is applicable to both men and women. “To be oneself” in the true sense means to answer to the call of the deepest self. We can only achieve our “fullness of being” if we do so. The mind invents all manner of goals and projects and ideals to be pursued, but ultimately all that we do produces only frustration and emptiness if we act in a way that does not fundamentally satisfy the needs of our deepest, pre-mental, bodily nature.

What Lawrence says here is applicable to both men and women. “To be oneself” in the true sense means to answer to the call of the deepest self. We can only achieve our “fullness of being” if we do so. The mind invents all manner of goals and projects and ideals to be pursued, but ultimately all that we do produces only frustration and emptiness if we act in a way that does not fundamentally satisfy the needs of our deepest, pre-mental, bodily nature.