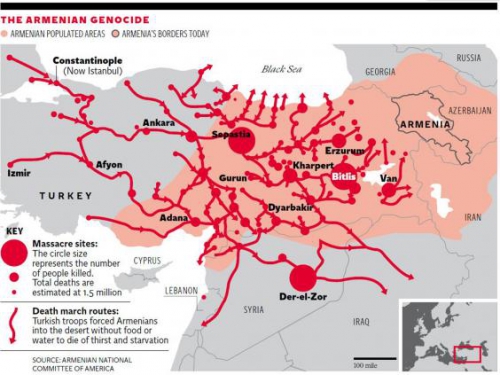

When the Young Turk government dragged the Ottoman Empire into the First World War on the side of the Central Powers, their aim was to create a pan-Turkic empire incorporating Turkic lands that were part of the Russian Empire. A major impediment to these plans were the Christian minorities of Eastern Anatolia: the Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians, who naturally looked to Russia as a potential ally and protector. Thus the Young Turks hatched a plan to exterminate these groups.

The Promise, helmed by Irish director Terry George, is a story from the Armenian genocide, which began with the arrest of the leaders of the Armenian community in Constantinople on April 24, 1915. Most of them were later murdered. Young Armenian men were inducted into the Turkish military, where they were put to work as slave laborers building roads and railroads, then massacred. Older and infirm men, as well as women and children, were marched out of their towns and villages, ostensibly to be relocated to Syria, then massacred. All told, 1.5 million Armenians were killed, as well as 450,000 to 750,000 Greeks and 150,000 to 300,000 Assyrians. Most survivors fled abroad, essentially ridding the heartland of the Empire, which is now modern-day Turkey, of Christians.

The Promise is an excellent movie: a visually sumptuous, old-fashioned period film — a story of love, family, and survival set against the backdrop of a decadent and crumbling empire, the First World War, and the 20th century’s first genocide. In terms of visual grandeur and emotional power, The Promise brought to mind David Lean’s Doctor Zhivago. Although some have criticized The Promise for making the Armenian genocide the backdrop of a love triangle, what did they expect? A documentary? Besides, The Promise is no mere chick flick. It is a genuinely moving film, with a host of excellent performances, not just a predictable, cardboard melodrama — as fun as those can be. And although the comparison actually cheapens this film, if you like historical soaps like Masterpiece Theatre, Downtown Abbey, and Merchant-Ivory films — or high-order chick flicks like Anthony Minghella’s The English Patient — you will love The Promise.

Another delightful, old-fashioned feature of The Promise is its original orchestral score by Lebanese composer Gabriel Yared, who incorporates Armenian music. There is also gorgeous music in a church scene in which the great Armenian composer and musicologist Father Komitas [2] is portrayed singing on the eve of his arrest along with the other leading Armenians of Constantinople. (He survived but was driven mad by his ordeal and never composed again.)

The Promise focuses on Mikael Boghosian (Oscar Isaac), a young Armenian from a small village in southern Turkey who takes the dowry from his betrothal (the promise of the title) to Marak (Angela Sarafyan) to enroll in the Imperial Medical Academy in Constantinople. There he meets and falls in love with Ana Khesarian (Charlotte Le Bon), the French-educated daughter of a famous Armenian violinist, who is the lover of American journalist Chris Myers (Christian Bale). When the genocide begins, Mikael’s wealthy uncle is arrested, Mikael is conscripted as a slave laborer, and Ana and Chris work to document the atrocities and save lives. Eventually Mikael makes his way back to his village, finds his family, and marries his betrothed. He then encounters Ana and Chris and joins forces with them to try to save his family, his village, and other Armenians.

All the leading characters in The Promise are convincingly three-dimensional and well-performed. Oscar Isaac is excellent as Mikael, as is Charlotte Le Bon in the role of Ana. Every Christian Bale fan, of course, will want to see this film. Although this is not his most compelling character, it is an enjoyable performance nonetheless. My favorite minor character was Mikael’s mother Marta, played by the charismatic, husky-voiced Persian actress Shohreh Aghdashloo.

I recommend that all my readers see The Promise. It is worth seeing simply as a film, but it is also worth seeing to send a message. For powerful forces are working together to make sure that you do not see this film. A movie about the Armenian genocide is viewed as a threat by the Turkish government and the organized Jewish community, both of which oppose designating the Armenian tragedy a genocide. The Turks wish to evade responsibility, and the Jews fear any encroachment on their profitable status as the world’s biggest victims. Before the film’s release, Turkish internet trolls spammed IMDb [3]with bogus one-star reviews. Since the film’s release, the Jewish-dominated media has given the film tepid to negative reviews. Given the film’s obvious quality, I suspect an organized campaign to stifle this film. Don’t let the bastards win.

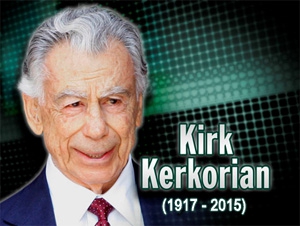

For many years, I illustrated the Jewish will-to-power compared to other market-dominant minorities with the story of Kirk Kerkorian’s purchase of MGM Studios. Kirk Kerkorian was a self-made Armenian-American billionaire. At his peak, he was worth $16 billion and was the richest man in California. In 1969, Kerkorian bought MGM, and instead of seeing it as an opportunity to influence the culture by making movies and television shows, he sold off a lot of its properties and basically turned it into a hotel company. Before he died at the age of 98, however, Kerkorian realized the cultural value of movies and bankrolled The Promise with $100 million.

Over his lifetime, Kerkorian gave away more than $1 billion, spending most of it on helping the Republic of Armenia. If only white American billionaires had a shred of this sort of ethnic consciousness, White Nationalism would be flourishing. Until such figures emerge and start taking media power seriously, the Western mind will be nothing more than a battleground over which highly-organized Levantines fight for control. From a White Nationalist point of view, of course, this is an intolerable situation. But anything that challenges Jewish media hegemony is in the long-term interests of whites. White Nationalism, moreover, has many Armenian allies and well-wishers. So I regard The Promise not just as an excellent film, but as a positive cultural and political development. Thus we should wish it every success.

I can hardly wait for a movie about Operation Nemesis [4].

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg