dimanche, 29 mai 2011

Remembering Isadora Duncan, Pagan Priestess of Dance

Remembering Isadora Duncan:

Pagan Priestess of Dance

By Amanda BRADLEY

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

“In those far-off days which we are pleased to call Pagan, every emotion had its corresponding movement. Soul, body, mind worked together in perfect harmony.”—Isadora Duncan

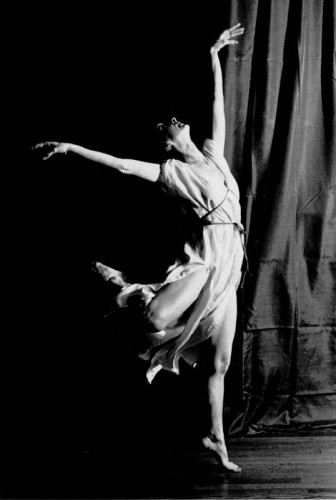

The life of Isadora Duncan was marked by opposition to every aspect of bourgeois modernity. Born on May 27, 1878, she was devoted to creating a form of dance, religious in nature, worthy of interpreting Greek tragedies and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (1). Today she often is celebrated as the creator of “modern dance”; such a description is a misnomer, at best, as her entire life was a conscious revolt against the modern world. Sometimes she turned to the world of Tradition; other times, her revolt was in the wrong direction—toward Communism, for example—but these ideological jaunts are understandable in light of her naivety and idealism.

A ‘Renaissance of Religion’ Through Dance

Isadora danced not solely as an art; she aspired to create a “dance which might be the divine expression of the human spirit through the medium of the body’s movement.” Ballet teaches that the central spring of movement is the base of the spine, from which all limbs move. But Isadora thought this produced “artificial mechanical movement not worthy of the soul,” much like an “articulated puppet” (2). After hours standing in meditation, she discovered the true central spring of movement in the solar plexus:

Isadora danced not solely as an art; she aspired to create a “dance which might be the divine expression of the human spirit through the medium of the body’s movement.” Ballet teaches that the central spring of movement is the base of the spine, from which all limbs move. But Isadora thought this produced “artificial mechanical movement not worthy of the soul,” much like an “articulated puppet” (2). After hours standing in meditation, she discovered the true central spring of movement in the solar plexus:

I . . . sought the source of the spiritual expression to flow into the channels of the body filling it with vibrating light—the centrifugal force reflecting the spirit’s vision. After many months, when I had learned to concentrate all my force to this one Centre I found that thereafter when I listened to music the rays and vibrations of the music streamed to this one fount of light within me—there they reflected themselves in Spiritual Vision not the brain’s mirror, but the soul’s, and from this vision I could express them in Dance. (3)

Isadora had trouble explaining this to adults, even artists, but even the youngest child could understand how to listen to music with the soul. She taught her students to let the inner self awaken within them, and from then on, “even in walking and in all their movements, they possess a spiritual power and grace which do not exist in any movement born from the physical frame, or created from the brain” (4). Her dance was as focused on inward movement as outward. Such children were able to captivate audiences that even great artists could not.

Raised in America, Isadora moved to Europe as a young adult “to bring about a great renaissance of religion through the Dance” (5). Though inspired by the Greeks’ religiosity, she called her style the “Dance of the Future.” Art that is not religious is not art, she said, but mere merchandise.

Isadora’s interest in paganism coalesced when she, her siblings, and mother moved to Greece in 1903. They started wearing Greek tunics and sandals, a tradition Isadora continued for the rest of her life. She briefly had dresses made by Paul Poiret, but later described it as a fall from a sacred to a profane art. She said that a flower in the hands of a woman was more beautiful than if she held all the world’s diamonds and pearls.

The family bought a piece of land with a view of the Acropolis and started to build a temple based on the Palace of Agamemnon. They planned to rise at dawn and greet the sun with song and dance; spend the mornings teaching the local villagers song and dance and converting them to Greek paganism; meditate in the afternoons; hold pagan celebrations in the evenings; and be vegetarians. They soon realized the impossibility of building such a grand house and of finding water on their land. Instead, they held competitions for the most authentic Greek songs and formed a chorus of boys to create an original Greek chorus (6). They determined to make a pilgrimage after reading the Eleusinian Mysteries and, to propitiate the gods, danced rather than walked the 13-and-a-half-mile trip to Eleusina.

But the same thing happened in Greece that Isadora experienced her entire life: She ran out of money and abandoned her vision. Fiscal responsibility was unknown to this family of artists; large sums were made from successful tours or generous donors, but quickly spent in extravagance, and the subsequent poverty derailed many plans. Isadora’s success also was interwoven with harsh critiques of her work. The Berlin Morgen Post, for example, ran a Q&A with dance masters titled “Can Miss Duncan Dance?” Isadora’s letter in reply posed the question of whether a dancing maenad whose sculpture was in the Berlin Museum could dance, never having danced en pointe (7).

Isadora’s life was marked by a variety of ventures, which often ended if she had to compromise her art. One started when Cosima Wagner called on Isadora to discuss her late husband’s distaste for ballet and his “dream for the Bacchanal and the Flower Maidens.” And so Isadora went enthusiastically to Bayreuth to create a dance for the Bacchanal in Tannhäuser in 1904. Isadora insisted on dancing in a transparent tunic, despite Cosima’s pleadings. She maintained that women’s bodies were beautiful, and that even in her risqué tunics, her costumes were less vulgar than those of chorus girls. She said she would rather dance nude than walk down the streets in “half-clothed suggestiveness” like American women. One day she couldn’t resist sharing her revelation that “Musik-Drama kann nie sein,” and her tenure at Bayreuth ended when she said the Wagner’s errors were as great as his genius.

Isadora’s first school of dance was started in Grunewald, Germany, and held up the young girls of ancient Sparta as “the future ideal.” She maintained her spiritual vision when founding her second school, in Paris, housed in a temple of dance called the Dionysion. Her vision for the school was inspired by the “Seminary of Dancing Priests of Rome” (the Salii), who “danced before the people for the purification of those who beheld them. . . . with such happy ardour and purity, that their dance influenced and elevated their audience as medicine for sick souls” (8). She planned to build a theatre in which her students would dance the chorus to Greek tragedies:

I pictured a day when the children would wend their way down the hill like Pan Athene, would embark on the river and, landing at the Invalides, continue their sacred Procession to the Panthéon and there celebrate the memory of some great statesman or hero. (9)

Her school was intended to be the start of a global crusade: Her young adepts would inspire others and eventually change the world. She said once that when rich, she would rebuild the Temple of Paestum and found a college of priestesses of the dance.

Isadora had two children, a girl by theatre designer Gordon Craig and a boy by Paris Singer, heir to the sewing machine fortune. Like all women, Isadora was more a mother at heart than an artist, and anything else she could do in life paled next to the joy of her children. In describing her daughter’s birth, she said, “Oh, women, what is the good of us learning to become lawyers, painters or sculptors, when this miracle exists? Now I know this tremendous love, surpassing the love of man . . . What did I care for Art! I felt I was a God, superior to any artist” (10). Though her art was often at odds with her romantic relationships and society, her children became her best students. Both were killed in an automobile accident, drowning in the Seine in 1913. Her longing for another child was so immense that she begged a stranger, the sculptor Romano Romanelli, to impregnate her. She gave birth with the drums of World War I pounding outside. The baby died shortly after childbirth and her school was turned into a hospital.

During the war, Isadora moved her school to New York, at the peak of the jazz age. There she found that men and women of the best society spent their time “dancing the fox trot to the barbarous yaps and cries of the Negro orchestra” (11). She became completely disillusioned with the spirit of her home country, stating that the jazz rhythm expresses “the primitive savage” and referring to the “tottering, ape-like convulsions of the Charleston [5].” She wanted a dance for America, one springing from Walt Whitman and that had “nothing in it of the inane coquetry of the ballet, or the sensual convulsion of the Negro.” She did not like Henry Ford’s suggestion that the young people dance the waltz or minuet, as the minuet was servile and the waltz an expression of “sickly sentimentality” (12).

Although she has been called a racist and xenophobe, and the book Hitler’s Dancers refers to her national feminism as excluding all people of color and who don’t match the eugenic claims of the nation, Isadora’s racial tendencies were not at the heart of her philosophy of dance. She said she believed that all people were her brothers and sisters, and in the great love for humanity shared by Christ and the Buddha.

Her sister Elizabeth, however, took a different path when she took over the school founded in Germany. Elizabeth’s husband was a “fanatical” Nazi who spoke out against Jewish influence in modern dance productions, and “racial hygiene” was part of the curriculum. Isadora’s Greek paganism was combined with Germanic myth and Nordic rites to turn the female dance into “creative prayer” (13). The prologue to Leni Riefenstahl’s Fest der Völker (Festival of Nations) has been called a fulfillment of Isadora’s “vision of a dance of Beauty and Strength” (14). (Riefenstahl was herself a dancer in a style similar to that of Isadora prior to a knee injury.)

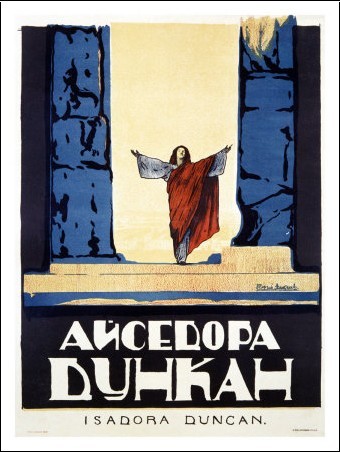

After her disillusionment with America, Isadora became equally disgusted with bourgeois Europe and believed that through communism, Plato’s ideal state might be created on earth. She went to Moscow after the Russian Revolution when invited by the government to found a school there in 1921. She said the American rich were not remnants of any true aristocracy (of which she spoke positively); they had no appreciation for true art but only “money, money, money.” Russia held promise that all children would be able to experience the dance and opera.

When she returned to America for a tour, Isadora was labeled a “Bolshevik hussy” and deprived of her American citizenship. Shortly before she left the country for the final time, she published an article in Hearst’s American Weekly that criticized the U.S. for its Puritanism, commercialism, and marriage laws. She had her own brand of feminist eugenics: When the communist State provided for children, mothers would be free to experiment with the best fathers for fit children in the same way botanists experiment with the best fertilizers for fit seed (15).

After several years in Moscow, she found the regime did not allow for full expression of her art and most of the money for her school was withdrawn. The remainder of her life was spent with tours, a short marriage to the poet Sergei Yesenin that was marked by widely publicized domestic rows, romantic relationships, and financial difficulties. She died on September 14, 1927, at the age of 50, when her long scarf got tangled in a rear wheel and axel of an Amilcar, either strangling her or throwing her from the vehicle.

After several years in Moscow, she found the regime did not allow for full expression of her art and most of the money for her school was withdrawn. The remainder of her life was spent with tours, a short marriage to the poet Sergei Yesenin that was marked by widely publicized domestic rows, romantic relationships, and financial difficulties. She died on September 14, 1927, at the age of 50, when her long scarf got tangled in a rear wheel and axel of an Amilcar, either strangling her or throwing her from the vehicle.

The Far Right is filled with converts from the Far Left. Had Isadora lived longer, it’s easy to imagine her finding a philosophical home with her sister Elizabeth and her husband, in the pagan strains of National Socialism, especially in its glorification of the peasant classes and motherhood (though her dance may have been labeled degenerate). Had she lived but a year longer, she may have been inspired by the anti-Christian, pagan revolution described in Julius Evola’s Pagan Imperialism. Or, despite her friend Eleanora Duse’s dramatic break-up with Gabriele d’Annunzio, she may have taken her Dance of the Future to Fascist Italy.

Upbringing, Education, and Feminism for Future Mothers

Isadora was successful in teaching her style of dance to young children, enabling them to connect with their inner selves and develop a natural grace. When they grew older, however, “the counteracting influences of our materialistic civilization took this force from them—and they lost their inspiration” (16). Isadora felt that she was able to withstand the materialistic forces of the modern world because of her unusual upbringing.

Isadora was the youngest and most willful of four artistic children. Her mother was an accomplished pianist and devout Catholic, who divorced when Isadora was young and promptly became an atheist. Her father made and lost several fortunes over his lifetime and was largely absent from their life.

The Duncan children had a highly unconventional upbringing in San Francisco. They were free to wonder about town, had no strict bedtimes, and were never disciplined. They moved frequently since they often were unable to pay rent, but their poverty made their life an experiment in asceticism. “My mother cared nothing for material things and she taught us a fine scorn and contempt for all such possessions as houses, furniture, belongings of all kinds,” wrote Isadora. “It was owing to her that I never wore a jewel in my life. She taught us that such things were trammels” (17). Isadora bargained for free food and extended credit at the butcher’s and baker’s, and peddled her mother’s knitting door-to-door. She was always grateful for their poverty and credited her hardships with a Nietzschean master-creating power:

When I hear fathers of families saying they are working to leave a lot of money for their children, I wonder if they realize that by so doing they are taking all the spirit of adventure from the lives of those children. For every dollar they leave them makes them so much the weaker. The finest inheritance you can give to a child is to allow it to makes its own way, completely on its own feet. . . . I did not envy these rich children; on the contrary, I pitied them. I was amazed at the smallness and stupidity of their lives. (18)

Isadora’s young life alternated between joy and terror. Her mother often was red-eyed from tears, only knowing how to suffer and weep as a Christian, an attitude that her daughter found appalling. Before ever reading him, Isadora said she instinctively embraced Nietzschean philosophy.

Isadora started her first school of dance at age six. Her classes became so large, and she was making much-needed money, that she dropped out of school at age 10. Already she was developing her own system of dance, often inspired by poetry. It was at this young age, after being sent to a famous ballet teacher for lessons, that she developed the view that the dance formed in the Italian Renaissance was “ugly and against nature.”

Her education did not stop with her exit from school. She and her siblings had enchanted evenings, when their mother played Beethoven, Schumann, Schubert, Mozart, and Chopin and read them Shakespeare, Shelley, Keats, Browning, and Burns. At one point the children opened a theater and took their troupe on a small tour on the California coast. Isadora started a newspaper and embarked on a program of self-study at the public library in Oakland.

Her education did not stop with her exit from school. She and her siblings had enchanted evenings, when their mother played Beethoven, Schumann, Schubert, Mozart, and Chopin and read them Shakespeare, Shelley, Keats, Browning, and Burns. At one point the children opened a theater and took their troupe on a small tour on the California coast. Isadora started a newspaper and embarked on a program of self-study at the public library in Oakland.

Isadora’s opposition to marriage sprung from her parents’ divorce and was cemented after reading George Eliot’s Adam Bede, about an unmarried pregnant girl who exposes her baby rather than endure humiliation and ostracism in her village. “I decided, then and there, that I would live to fight against marriage and for the emancipation of women and for the right for every woman to have a child or children as it pleased her, and to uphold her right and her virtue,” she recalled (19). Her opposition to marriage was always due to two factors: an opposition to divorce (especially when a woman’s children could be taken from her), and a desire for women to have more freedom to bear children. When women told her that marriage was needed to secure the father’s support of children, Isadora responded that she did not think men so lowly.

Isadora’s romantic encounters also led her to discount the viability of marriage for artists. Time after time she fell in love, only to have the man ask her to renounce her art in order to support his. When her first lover, a Shakespearean actor, took her to look at apartments she felt “a strange chill and heaviness” and asked what their married life would be like. “Why, you will have box each night to see me act, and then you will learn to give me all my répliques and help me in my studies” (20). This first heartbreak led to her being placed briefly in a clinic and her subsequent notions that only one spiritual path was possible:

I believe that in each life there is a spiritual line, an upward curve, and all that adheres to and strengthens this line is our real life—the rest is but as chaff falling from us as our souls progress. Such a spiritual line is my Art. My life has know but two motives—Love and Art—and often Love destroyed Art, and often the imperious call of Art put a tragic end to Love. For these two have no accord, but only constant battle. (21)

Isadora is considered modern for her bisexuality; she had one confirmed relationship with a woman. She considered Plato’s Phaedrus the most exquisite love song ever written, and, like the ancient Greeks, believed “the highest love is a purely spiritual flame which is not necessarily dependent on sex” (22). No doubt she would have appreciated J. J. Bachofen’s elucidation on the differences between the Thracian’s sensual homosexuality versus the Lesbian women, who chose Orphism over Amazonism: “The sole purpose was to transcend the lower sensuality, to make physical beauty into a purified psychic beauty” (23).

Isadora continued her education as an adult, spending hours at the library of the Paris Opera to study the history of dance. In her early adulthood, she said the only dance masters she could have were Jean-Jacques Rousseau (for Emile), Whitman, and Nietzsche. Later she said the three great precursors of her Dance of the Future were Beethoven, Nietzsche, and Wagner: Beethoven created the Dance in mighty rhythm, Wagner in sculptural form, Nietzsche in Spirit (24).

Isadora Duncan was a soul from another age. In ancient Greece she might have been at home with Sappho, or as a priestess or hetaera. Although she always claimed to need “more freedom,” it was in part the freedoms of modernity that made her path difficult. In her tragic, yet joyful, life, she maintained a link to a religiosity that almost has vanished. Isadora was not merely a woman or artist; like her beloved Zarathustra, she lived up to the title of “dancing philosopher.”

Notes

1. Isadora’s birthday is believed to be May 27, 1878. Her baptismal certificate, discovered in 1976, records the date as May 26, 1877.

2. Isadora Duncan, My Life (New York: Liveright Publishing, 1955), p. 75.

3. My Life.

4. My Life, p. 76.

5. My Life, p. 85.

6. My Life, p. 129.

7. Isadora Speaks: Writings & Speeches of Isadora Duncan, ed. Franklin Rosemont (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr, 1994), p. 34.

8. My Life, p. 302.

9. My Life, p. 303.

10. My Life, p. 196.

11. My Life, p. 318.

12. My Life, pp. 341–42.

13. Lilian Karina and Marion Kant, Hitler’s Dancers: German Modern Dance and the Third Reich, trans. Jonathan Steinber (New York: Berghahn Books, 2004), pp. 33–34.

14. Terri J. Gordon, “Fascism and the Female Form: Performance Art in the Third Reich,” in Sexuality and German Fascism, ed. Dagmar Herzog (New York: Berghahn Books, 2004), p. 14.

15. Isadora Speaks, p. 131.

16. My Life, p. 76.

17. My Life, p. 22.

18. My Life, p. 21.

19. My Life, p. 17.

20. My Life, p. 107.

21. My Life, p. 239.

22. My Life, p. 285.

23. J. J. Bachofen, Myth, Religion, and Mother Right, trans. Ralph Manheim (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967), p. 204.

24. My Life, p. 341.

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2011/05/remembering-isadora-duncan-pagan-priestess-of-dance/

00:05 Publié dans art | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : isadora dunca, danse, art, avant-gardes, chorégraphie, chorégraphes, années 20, années 30, paganisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les commentaires sont fermés.