Matthew Carr

Matthew Carr

Blood and Faith: The Purging of Muslim Spain

New York: New Press, 2009

There is something about the Spain of centuries past that is so dreadfully modern. One situation was the presence of large numbers of Muslim Moors after the conquest of Granada in 1492. The Moorish community arrived in Spain during the Islamic conquest of Iberia which started in 711 AD.

The Islamic conquest of Spain is unique in that a less advanced civilization conquered a more advanced one. It is also unique in that the conquerors came from the south of the conquered. The Romans were situated south of many of their conquests, but they were a very advanced civilization indeed and Rome itself is pretty far north — 41 degrees Latitude.

The Moorish conquest occurred prior to the revolution in military affairs caused by gunpowder. In that situation, “barbarians,” be it Mongols, Vikings, or Arabs armed with swords and spears could use what the US Army calls “the characteristics of the offense.” Simply put: surprise, concentration, audacity, and tempo to take over. In other words, you get a bunch of healthy and armed young men and attack some place just before dawn.

While there is much talk of an “Islamic Golden Age” as well as the appearance of “science” going on in Moorish Cordoba, it is clear from the historical record of the Reconquista that the Spanish recovered their balance and started to become economically and militarily dominant over the Moors rather quickly because they were a superior civilization in all respects. The “Islamic Golden Age” is probably a fiction invented by historians with no experience with Muslims or Islamic society while having an anti-Catholic or anti-Spanish bias. By the late Middle Ages, there is a sense that a final Spanish victory in Iberia was only a matter of time.

The last Moorish stronghold at Granada fell in 1492. The final battle was not a straight-up, blood-soaked military conquest; the last Moorish chieftain Boabdil turned over the keys to the city to Ferdinand and Isabella when it became clear that further Islamic resistance was futile. While Ferdinand and Isabella had advisors that wished to immediately extirpate Islam from Spain, Royal policy became one of toleration — at least in the short term.

Granada and its surrounding area was an extension of North Africa. The streets in the towns were narrow and mosques abounded. The villages in the hinterland of Granada were also populated by Moors. A large Moorish population also lived around Valencia, on the east coast of Spain. After the fall of Granada, the Moors remaining in Iberia became known as Moriscos, i.e. “little Moors.” Castilian settlers slowly moved into Granada and its surrounding region.

The Morisco Wars

Carr catalogs the sharp problems between the Moriscos and the native Iberian Spanish. Indeed, the Moriscos and Iberians lived in parallel societies. The Moriscos revolted in Granada in 1500. Although there were some setbacks, the Spanish military crushed the revolt and the Muslims in Granada were officially converted in 1501.

Meanwhile, in Valencia, there was a large population of Moriscos who worked on the estates of the landed Spanish gentry. Moriscos were protected by the Spanish wealthy, who felt that they couldn’t manage without cheap Morisco labor. The parallels of this situation to non-white, illegal immigration today with regards to the wealthy are obvious. The region was also plagued with crime. In 1521, native Iberian Spaniards revolted. Estates were burned and the Morisco population was converted or put to the sword. The Spanish establishment regained control by 1522, but the situation had changed. Valencia’s Moriscos were “Christians,” but suspicion and racial tensions remained.

The ugliest war started in the village of Cadiar on Christmas Eve in 1568. Moriscos from the village murdered Spanish soldiers garrisoned in the town in their beds. The revolt spread to Granada and the rest of the Alpujarras Mountain Range. The Christians managed to hold Granada and the Spanish military eventually suppressed the rebellion. The fighting was vicious, not unlike the ugly, no-holds-barred fighting in Bosnia in the early 1990s.

The parallels of this situation were also like that of the non-white problems in the United States starting with the “civil rights” disorders from the 1960s. Like America, being at the height of its power and dealing with an existential threat from the Soviet Union in LBJ’s time, Spain was at the height of its power and dealing with an existential threat in the Mediterranean from the Ottoman Empire. In the same way many in the US viewed black rioting as part of a greater Communist conspiracy, so too did many Spaniards view Moriscos as a potentially subversive force. There is considerable evidence to show that “civil rights” was supported to a degree by Communists in the 1960s, and even more evidence between the lines in Blood and Faith that show Moriscos were helping out North African corsairs and other Muslims in various ways; although not all the time by all the Moriscos.

Civic Nationalism & Limpieza de Sangre

Spanish policy towards its non-native Iberian Moorish and Jewish populations was dual-natured. On the one hand, the Spanish government used the Roman Catholic Church as a vector for civic nationalism. As long as a Jew or Morisco converted, these populations could be considered loyal Spanish citizens. However, the magic of civic nationalism never really took. The Jewish situation is well known, but the Morisco situation needs further explanation. Pastoral care for Moriscos was something of a boondoggle. If a priest showed up at all, they often took the money and did little for the community. Moriscos also never fully converted. After the fall of Granada, Islamic scholars urged Moriscos to practice taqiyya, a form of deception allowed under Islamic law if a Muslim community was under threat. The Spanish were never able to really trust the converted Moriscos.

Again, the parallels to non-whites in modern America and modern Europe abound. Like black football players kneeling during the national anthem, Moriscos with blank faces at mass represented a rejection of the rituals of civic nationalism. Identity issues also bubbled up regarding Morisco clothing. Morisco women wearing a veil and Morisco men wearing a turban were perceived to be carrying out a hostile act. (Much like the perception of hijab wearers in Yorkshire or Paris today by modern Europeans.) Even funeral practices caused controversy. If the dead were washed and buried in a Muslim way, community tensions and suspicions arose. Moriscos spoke Spanish with a different accent from the native Iberians, but not in all places or at all times.

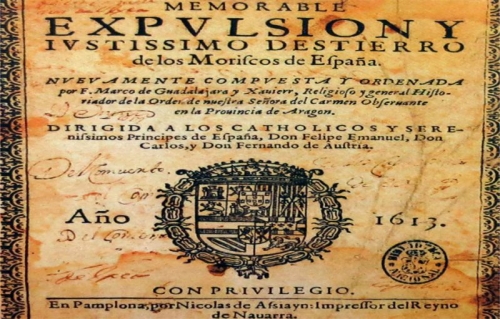

Eventually, it became clear to the Spanish intellectual and political elite that a policy of Limpieza de Sangre (purity of blood) was the only way to deal with the Morisco problem. That is to say, citizenship became based on racial relatedness rather than belief in an ideology. Proposals for expelling the Moriscos first came up in 1492, but it took until 1609 for any action to be taken. There were all sorts of sticking points: the wealthy wanted pliable Third World workers, and many in the Catholic hierarchy genuinely cared about the immortal souls of the Moriscos. Some felt that the Moriscos would empower the Islamic World if they were sent to North Africa. Eventually, the problems with the Ottoman Turks, the Islamic corsairs, fear of demographic eclipse, and years of metapolitical activism by patriotic native Iberian Spanish monks, friars, and intellectuals combined to bring about expulsion.

The affair started in Valencia and then other regions of Spain carried out their own expulsions. Some Moriscos were able to sell their property and make new lives in their ancestral North Africa. Some Moriscos were impoverished by the expulsion. It is certain that a few Moriscos were robbed and murdered by unscrupulous sailors or soldiers charged with evacuating them. This was not Spanish policy, though; those caught doing such deeds were arrested and often hanged. A few Moriscos returned to a different region of Spain from where they were expelled and blended in as though they were native Iberians.

Several items stick out:

- Civic nationalism through Roman Catholicism failed to work in part because the Moriscos deliberately rejected the idea and antagonized the Spanish when they clearly failed to perform civic nationalist rituals.

- The Spanish paid an economic price when expelling the Moors. In particular, the economy of Valencia experienced a setback. One pays to sustain the burden of vibrant diversity and one pays even more to remove vibrant diversity.

- Regardless, the real economic shock to the Spanish Empire was the Spanish inability to engage in complex commercial activities. The Spanish wars with the Dutch and English contributed to Spanish Imperial decline, not the removal of the Moriscos. This book implies that the removal of the Moriscos was a major factor — I disagree.

- In light of Rotherham grooming gangs, Salafi Jihadist terrorism, ISIS, and street crime observed today, one can easily infer that Moriscos were less than stellar citizens. There really were Barbary corsairs colluding with Moriscos to capture Christian slaves. Had the Moriscos remained in Spain, there would have been another Morisco War sometime in the mid-1600s.

On a final note, albeit from an outsider’s perspective, it is unfortunate that the tension in Spain between the civic nationalism of the Roman Catholic Church and the Inquisition versus the concept of Limpieza de Sangre was never reconciled by separating the two concepts. For many Spaniards, their nationality became defined by their Roman Catholicism. Spain became a proposition nation based around an ideology when it didn’t need to be. As a result, Spanish society had a far more difficult time absorbing ideas that clashed with Catholicism than other European groups such as the English or French. This helped contribute to cultural stagnation and the rise of an anti-clerical faction in Spanish culture that was a toxic mixture of Jacobin leftism and solid logical reasoning. This problem contributed to Spain’s appalling and tragic civil war of the 1930s.

Matthew Carr, Blood and Faith’s author, is hostile to Spain’s expulsion of the Moriscos as well as Europe’s increasing anti-Islam stances today. However, this book is very interesting. Indeed, Mr. Carr should have the final word:

If some contemporary “Islamic threat” narratives echo medieval anti-Islamic polemics in their depictions of Islam as an inherently aggressive “religion of the sword,” the construction of the contemporary Muslim enemy often fuses culture, religion, and politics in ways that would not be entirely unfamiliar to a visitor from Hapsburg Spain. Just as sixteenth-century Spanish officials regarded the Moriscos as “domestic enemies” with links to the Barbary corsairs and the Ottomans, so journalists and “terrorism experts” increasingly depict Europe’s Muslims as an “enemy within” with links to terrorism and enemies beyond Europe’s borders. Just as inquisitors regarded Morisco communities as inscrutable bastions of covert Mohammedanism and sedition, so some of these commenters depict a continent pockmarked with hostile Muslim enclaves, “Londonistans,” and no-go areas that lie entirely outside the vigilance and control of the state, in which the sight of a beard, a shalwar kameez (unisex pajamalike outfit), or a niqab (veil) is evidence of cultural incompatibility or refusal to integrate.”

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.