lundi, 01 juillet 2013

Keith Lowe - Savage Continent

Keith Lowe - Savage Continent

00:05 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : keith lowe, années 40, deuxième guerre mondiale, seconde guerre mondiale, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 31 mars 2013

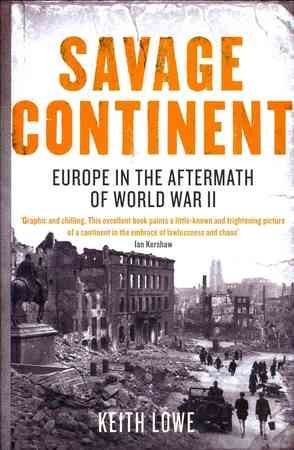

Savage Continent

Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War Two, By Keith Lowe

As the author points out, the Second World War did not end in 1945. In large parts of the continent, the contest lasted a lot longer as Polish, Ukrainian, Baltic and Greek partisans battled on in the mountains and forests of Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean. Some of these stories, such as the post-war travails of the Greeks, are well known to Western audiences, but the activities of the Lithuanian, Latvian and Estonian anti-Soviet "Forest Brothers" are not. Perhaps the most arresting fact in this compelling book is that the last Estonian guerrilla fighter, August Sabbe, was killed as late as 1978, trying to escape capture.

As the author points out, the Second World War did not end in 1945. In large parts of the continent, the contest lasted a lot longer as Polish, Ukrainian, Baltic and Greek partisans battled on in the mountains and forests of Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean. Some of these stories, such as the post-war travails of the Greeks, are well known to Western audiences, but the activities of the Lithuanian, Latvian and Estonian anti-Soviet "Forest Brothers" are not. Perhaps the most arresting fact in this compelling book is that the last Estonian guerrilla fighter, August Sabbe, was killed as late as 1978, trying to escape capture.

Even where there was no fighting, Lowe demonstrates, Europe was in flux. A contemporary observer described Germany, the crossroads of the continent, as "one huge ants' nest", in which everyone was on the move. There were refugees everywhere, some trying to escape the victors, others returning to their homes. Millions of German prisoners of war were crammed into insanitary Anglo-American camps in the West; and they were the lucky ones, unlike those captured by the Russians and taken to camps in Siberia, or murdered en route. Almost everywhere, the Nazi collapse was followed by a bloody settling of scores against real or alleged collaborators. Lowe shows that the numbers affected in places like France to have been much exaggerated by subsequent myth-makers; in Yugoslavia, on the other hand, the reckoning was truly horrific, the more so as British troops were actively involved in sending men and women back to face certain death at Tito's hands.

All this was accompanied by the greatest population shifts in Europe since the Dark Ages. These had, of course, begun during the war. Lowe notes the huge void left by the Nazi murder of the Jews, but he points out that it was not so much the Holocaust itself as the persistence of anti-Semitism in places like Poland and Hungary which persuaded so many survivors to make for Israel or the US. In eastern Poland and western Ukraine, new borders led to a massive exchange of populations attended by great hardship and brutality.

The principal post-war victims, however, were the Germans, systematically expelled by the Czechs and Poles from lands which they had settled for hundreds of years. Lowe describes these events too with admirable sensitivity, placing them squarely in the context of prior Nazi policies, without in any way justifying them.

Europe was also in political flux. The war had destroyed the standing of the old elites, and brought the Red Army into the heart of the continent. It was Soviet power, rather than the failure of the ancien regime as such, which underpinned the wave of Communist takeovers in Eastern Europe. Lowe describes the Romanian case in fascinating detail. Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland and Bulgaria all met broadly similar fates: red terror, arrests, expropriation of land and property, and executions. In Greece, the boot was on the other foot, as the right-wing government parlayed first British then American help into brutal victory over the communists. Lowe notes the "unpleasant symmetry" caused by Cold War imperatives without in any way denying that "the capitalist model of politics was self-evidently more inclusive, more democratic and ultimately more successful than Stalinist communism".

Europe was also in political flux. The war had destroyed the standing of the old elites, and brought the Red Army into the heart of the continent. It was Soviet power, rather than the failure of the ancien regime as such, which underpinned the wave of Communist takeovers in Eastern Europe. Lowe describes the Romanian case in fascinating detail. Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland and Bulgaria all met broadly similar fates: red terror, arrests, expropriation of land and property, and executions. In Greece, the boot was on the other foot, as the right-wing government parlayed first British then American help into brutal victory over the communists. Lowe notes the "unpleasant symmetry" caused by Cold War imperatives without in any way denying that "the capitalist model of politics was self-evidently more inclusive, more democratic and ultimately more successful than Stalinist communism".

Savage Continent is thus a fitting title for this book, and surely also an allusion to Dark Continent, Mark Mazower's brilliant history of the 20th century. Lowe's vivid descriptions of Europeans scrambling for scraps of food, rampant theft and "destruction of morals" are a timely reminder that a certain humility is in order when we look at less fortunate continents today. The author is also right to remind us, with respect to current travails in Iraq and Afghanistan, just how long it took to rebuild Europe and for democracy to take root – or to return.

That said, Lowe could perhaps have said more about the Europeans who emerged from the war with a new and uplifting vision: that the only way for the continent to prevent this from happening again, and to realise its full potential, was to chart a course towards greater unity. It was in the midst of the ruins described by this book that men such as Robert Schuman, Jean Monnet, Alcide de Gasperi and Altero Spinelli were taking the first steps towards what was to become the European Union. In this sense, Europe is a continent which contains not only the seeds of its self-destruction but also of its renewal.

Brendan Simms is a professor of history at Cambridge University; his 'Old Europe: a history of the continent since 1500' is published this summer by Allen Lane

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : keith lowe, livre, histoire, europe, affaires européennes, seconde guerre mondiale, deuxième guerre mondiale, barbarie, massacres |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook