dimanche, 23 janvier 2011

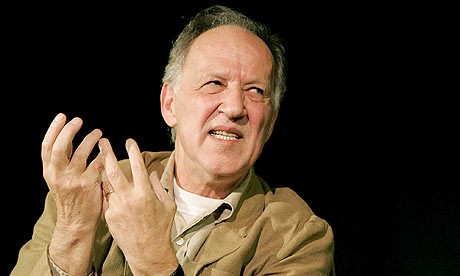

Werner Herzog - Finding ecstatic truth

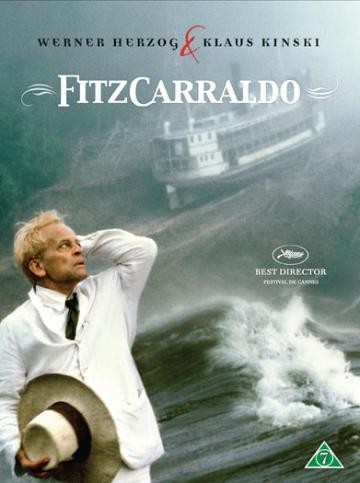

Werner Herzog, Conquest of the Useless: Reflections from the Making of Fitzcarraldo, Trans. By Krishna Winston (Ecco, 2009)

by Lawrence Levi

“One of the most revered filmmakers of our time, Werner Herzog wrote this diary during the making of Fitzcarraldo, the lavish 1982 film that tells the story of a would-be rubber baron who pulls a steamship over a hill in order to access a rich rubber territory. Later, Herzog spoke of his difficulties when making the film, including casting problems, reshoots, language barriers, epic clashes with the star, and the logistics of moving a 320-ton steamship over a hill without the use of special effects.”

“Originally published in the noted director’s native Germany in 2004, Herzog’s diary, more prose poetry than journal entries, will appeal even to those unfamiliar with the extravagant 1982 film. From June 1979 to November 1981, Herzog recounted not only the particulars of shooting the difficult film about a fictional rubber baron—which included the famous sequence of a steamer ship being maneuvered over a hill from one river to another—but also the dreamlike quality of life in the Amazon. Famous faces swim in and out of focus, notably Mick Jagger, in a part that ended up on the cutting room floor, and the eccentric actor Klaus Kinski, who constantly berated the director after stepping into the title role that Jason Robards had quit. Fascinated by the wildlife that surrounded him in the isolated Peruvian jungle, Herzog details everything from the omnipresent insect life to piranhas that could bite off a man’s toe. Those who haven’t encountered Herzog on screen will undoubtedly be drawn in by the director’s lyricism, while cinephiles will relish the opportunity to retrace the steps of one of the medium’s masters.” — Publishers Weekly

“As the book makes abundantly clear, this isn’t the jungle promoted by organizers of eco-tours: It’s a place of absurdity, cruelty and squalor; of incompetence and grotesquery; of poisonous snakes and insects from a fever dream; of Indians armed with poisoned arrows and Indians who craftily use the media. Hazards abound: greedy officials, deranged actors and drunken helpers… What transpires in the jungle, combined with his native astringency, moves [Herzog] to a curdled poetry, to ecstasies of loathing and disgust… Much of Herzog’s focus here is intensely physical, but he is also an imaginative cultural observer.” — San Francisco Chronicle

“…the befogged internal swirl of Herzog’s mind becomes an improbably apt vantage point from which to view the history of Fitzcarraldo. For all his maddening opacity…Herzog renders a vivid portrait of himself as an artist hypnotized by his own determined imagination.” — Mark Harris

“The journal entries that make up this disarmingly poetic memoir were penned over the course of the two and a half years it took Herzog to make his film Fitzcarraldo, for which he won the best director award at Cannes in 1982. Herzog’s earthy and atmospheric descriptions of the Amazon jungle and the Natives who live there among wild and domesticated animals in heavy, humid weather conjure a civilization indifferent to the rhythms of modernity. The impossible odds that conspired to stop production of the film and the sheer obstinacy it took to attempt it in the rain forest instead of a studio parallel the plot of the film itself: with the help of local Natives, Fitzcarraldo pulls a steamship over a steep hill to access rubber so he can earn enough money to build an opera house in the jungle. Herzog has made over 50 films during his prolific career.” — Donna L. Davey

“The journal entries that make up this disarmingly poetic memoir were penned over the course of the two and a half years it took Herzog to make his film Fitzcarraldo, for which he won the best director award at Cannes in 1982. Herzog’s earthy and atmospheric descriptions of the Amazon jungle and the Natives who live there among wild and domesticated animals in heavy, humid weather conjure a civilization indifferent to the rhythms of modernity. The impossible odds that conspired to stop production of the film and the sheer obstinacy it took to attempt it in the rain forest instead of a studio parallel the plot of the film itself: with the help of local Natives, Fitzcarraldo pulls a steamship over a steep hill to access rubber so he can earn enough money to build an opera house in the jungle. Herzog has made over 50 films during his prolific career.” — Donna L. Davey

“The acclaimed director’s diary of his time making Fitzcarraldo (1982). From the beginning, the film faced more challenges and uncertainties than most of Herzog’s other movies, and he composed a lengthy list that ended with the grim forecast that it could “be added to indefinitely.” Filming had to start anew after Jason Robards, the original lead and an actor Herzog came to scorn, abandoned the project halfway through due to illness, and Mick Jagger, set to play the lead character’s assistant, had to drop out to go on tour. When filming restarted, it was with German actor Klaus Kinski, a raving, unhinged presence in these journals-his volatility so alarmed the locals that they quietly asked the director if he wanted Kinski killed. Then there were the nightmarish logistics of the famous scene where a steamship is dragged over a small hill in the jungle, from one river to another. Herzog insisted that, as the central metaphor of the film, the event must be recorded without any compromise. (Much of the behind-the-scenes drama is recorded in Les Blank’s documentary Burden of Dreams.) Herzog’s journals effectively map the director’s dislocation and loneliness, but they also highlight his unique imagination and the profound effect the remote Peruvian location had on him. The writing is haunted by what Herzog came to see as the misery of the jungle, a place where “all the proportions are off.” He slept fitfully, when at all, and there is a hallucinatory quality to the journals-the line between what is real and what is imagined becomes nearly invisible. Recorded daily, with occasional gaps and fragments, Herzog’s reflections are disquieting but also urgent and compelling-as he notes, “it’s onlythrough writing that I come to my senses.“A valuable historical record and a strangely stylish, hypnotic literary work.” — Kirkus Reviews

“The filming of Werner Herzog’s 1982 epic, Fitzcarraldo, in the Amazonian depths of Peru seemed mythically doomed from its inception, something chronicled that same year in the documentary Burden of Dreams. The titular character, fueled by the volcanic ego of Klaus Kinski, wants to build an opera house in the wilds of Iquitos but first must get a 300-ton steamboat over a mountain. The German director’s personal journal from the marathon two-year shoot offers another angle, and it’s no surprise his entries are exquisitely detailed. Most of his films toe the same fine line – obsession and insanity – so naturally, he carried Fitzcarraldo’s burden.

It’s not explicit if, years later when he decided to translate and publish this, Herzog took a revisionist’s scalpel to his time in Peru. In the preface, he states it wasn’t a day-to-day diary of filming but rather “inner landscapes, born of the delirium of the jungle.” Throughout Conquest, Herzog is repeatedly disgusted by the jungle’s perversity and silent, seething “malice,” yet strangely amused by its dirty jokes.

Those highs and lows coil as one. For his dry reflections (“When you shoot an elephant, it stays on its feet for 10 days before it falls over”) and pangs of jungle hatred, there are equally beautiful scenes, as when Herzog thinks he feels an earthquake: “For a moment the countryside quivered and shook, and my hammock began to sway gently.” Herzog and Kinski’s tumultuous friendship is touched on, but not as deeply as in the great 1999 documentary My Best Fiend. Herzog mostly ignores the actor’s projectile insolence on set, though he does move him to a hotel when perturbed natives offer to kill him.

Elsewhere, a man chops off his own foot after a snakebite; a Peruvian general snaps and declares war on Ecuador; Herzog slaps an albino turkey; birds “scream” rather than sing, and insects look prehistoric; planes crash and limbs are split open. He sounds amazingly calm within these fevered inner landscapes – perhaps writing was therapy – but knows preserving history is important to myth. The crew, victorious, finally gets the boat over the mountain, and Herzog gets in one last joke. “All that is to be reported is this: I took part.” — Audra Schroeder

“A crazed epic about a rubber baron who drags a steamship across an Amazonian mountain range, Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (1981) set the bar absurdly high for cinematic realism. (There would be no special effects used.) Perhaps even more hair-raising were the stories that emerged from that shoot, including Peruvian border disputes, manic rages from actor Klaus Kinski and an unfortunate cinematographer forgotten overnight on a roaring rapids. Les Blank’s documentary of the making of the film, Burden of Dreams, is arguably superior to Fitzcarraldo itself.

Now comes a third narrative, director Herzog’s private journals, first published in Germany in 2004 and finally arriving stateside. Conquest of the Useless (from a line of dialogue in the film) adds significant details to the bigger picture, but also stands alone as a compellingly gonzo piece of reportage. Shrewdly omitting the better-known misadventures, Herzog focuses on his own determination and loneliness. And why not? It’s a diary. We start in the cush surroundings of Francis Coppola’s San Francisco mansion, circa the release of Apocalypse Now. Herzog toils on his script in the guest room while Sofia plays in the pool. A month later, he’s in Iquitos, Peru, observing animals as they eat each other.

As a read, Conquest flies along—but not because it’s especially plotty. Rather, it gathers its kick from the spectacle of a celebrity director escaping the late-’70s famescape into his own obsessions. Meetings with Mick Jagger are far less wild than Herzog’s mordant curiosity at the steamy rain forest and his vivid descent into what he calls the “great abyss of night.” When a local Peruvian fears the camera’s theft of his soul, Herzog tells him there’s no need to worry, but privately admits he’s lying.” — Joshua Rothkopf

“I am fascinated by Werner Herzog’s philosophical approach to life, and what he refers to as ecstatic truth. His early filmmaking roughly corresponds to the New German Cinema, a movement which sought to activate new ways to represent and discuss culture and reality. Ecstatic truth, as an idea, remains true to this bold and progressive ambition, hoping to capture a sense of reality that goes beyond straightforward empirical facts, or the contemporary conventions of European cinema.

Instead, ecstatic truth is a kind of spiritual affirmation that exists between the lines, or behind the superficial gloss of the on-screen images; and yet it is not spiritual in any theological sense, nor does it adhere to any cultural set of beliefs. To borrow a phrase from the title of Alan Yentob’s BBC documentary on Herzog, it is a truth ‘beyond reason’: highly subjective and deeply personal.

For me, what is most interesting about Herzog’s work is that he seeks to find a sense of ecstatic truth in the most extreme circumstances. Perhaps this is the only place it can be found, if it is to exist at all. His films are often structured around characters who are in some way at odds with the world, strangers in a universe divested of meaning and surrounded by ‘chaos, hostility and murder’. It sounds like a very fatalistic, Germanic philosophical approach, but I think that to dismiss it as negative or nihilistic is to miss Herzog’s point.

The concept of ecstatic truth ties into a loose cultural idea of spiritual enlightenment and individual empowerment, but it is without sentiment or naive idealism. It is a way of looking at the world as both brutal and chaotic, but embracing those qualities in nature for what they are. It accepts that humankind cannot dominate or control nature as such, but is enthusiastic about the engagement. On the set of Fitzcarraldo, deep in the jungle, Herzog speaks of the ‘obscenity of the jungle’, stating that even ‘the stars look like a mess’, and yet, in spite of this, he continues to love and admire the nature that surrounds him — perhaps ‘against [his] better judgment’.

Ecstatic truth does not imply security or stability, there are no great discoveries and no guarantees of empirical knowledge: in this sense it is a necessary conquest of the useless, a journey with no signposts or destinations. It is a continual task, undertaken not for the benefit of mankind but for the benefit of oneself. And I think that there is something perversely romantic and aspirational about Herzog’s approach; in many ways it feels reminiscent of Nietzsche roaming the wild mountains and finding peace in the wilderness.

To seek one’s individual sense of truth among the elements is surely as noble a project as any, and many of Werner Herzog’s films seem to be pursuing exactly that kind of philosophical aim: it is an attempt to create one’s place in the universe, or, as Herzog puts it, to continually search for ‘a deeper stratum of truth’ about oneself and the wider world.” — Rhys Tranter

“The 64-year-old German filmmaker Werner Herzog has long been as famous for his statements about film and culture as he has been for his actual movies. In speech and in writing, he inclines to aphorism rather than argument, issuing dicta with a hermetic self-containment bordering on the inscrutable. The 300-page Herzog on Herzog (2002) reads this way, as does his 12-point “Minnesota Declaration”, an impromptu manifesto delivered at the Walker Arts Center in Minneapolis in 1999. Herzog’s aphorisms teeter between the visionary and the bizarre, as these two points of the “Declaration” attest:

‘5. There are deeper strata of truth in cinema, and there is such a thing as poetic, ecstatic truth. It is mysterious and elusive, and can be reached only through fabrication and imagination and stylization.

10. The moon is dull. Mother Nature doesn’t call, doesn’t speak to you, although a glacier eventually farts. And don’t you listen to the Song of Life.‘

Herzog has become an object of cinematic fascination in his own right. Director Les Blank has made two documentaries starring his colleague: Burden of Dreams (1982) follows the making of Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, and Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe (1980) features Herzog cooking and devouring a leather boot while delivering pronouncements on the near-extinction of imagination, the need for artistic daring, and the difference between fact and truth. The collective word count of Herzog’s pronouncements about art and culture probably exceeds the words spoken by his characters onscreen (despite a prolific 55-film career). A master of elegant strangeness, Herzog has profited by this canny ability to expound and practice an artistic philosophy.

Once again, Herzog has managed to have his shoe and eat it, too. In Conquest of the Useless: Reflections from the Making of Fitzcarraldo, Herzog publishes the diary he kept from 1979 to 1981 while shooting (or, more often, waiting to shoot) his acclaimed film about a bombastic anti-hero in the Brazilian jungle. Thanks to Les Blank’s Burden of Dreams, the plagued history of Fitzcarraldo already holds a notorious place in filmmaking mythology: assistants died; actors became injured and ill; some of the local extras plotted to kill hot-blooded star Klaus Kinski. Typically, Herzog took these incidents as cosmic portents, telling Blank: “The trees here are in misery. The birds here are in misery – I don’t think they sing; they just screech in pain.” The essence of the jungle is “fornication and asphyxiation and choking and fighting for survival and growing and just rotting away”.

A darling of cineasts and prize committees, Werner Herzog is savvier than the humorless neurotic he sometimes plays on-screen and in his journals. He is fully aware of the cartoonishness of his morose Weltanschauung, but seems to relish situating himself at the juncture of comedy, melodrama, and nihilism. Of Conquest of the Useless’s 320 pages, this sort of vague cosmological pessimism probably accounts for some 50. The book finally shifts from being very funny (though we are never sure whether Herzog is an accomplice or an object of our laughter) to slightly dull.

That said, Conquest of the Useless is a singular book, so strong at many points that it could be read and appreciated by someone who had never seen a single Herzog film. In Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe, Herzog says: “Our civilization doesn’t have adequate images… That’s what I’m working on: a new grammar of images.” Without them, he says, we are doomed to “die out like dinosaurs.”

In contrast with this “new grammar of images”, Herzog sets the false images offered by television and advertisements. These “kill us” and “kill our language” because they lull instead of provoke, working within a familiar spectrum of wonder, desire, and repulsion. Herzog’s films can be interpreted as antidotes to this deadening complacency, and the countless strange moments in Conquest of the Useless as yet another curative, this time through the medium of language.

The book’s images of grotesque surrealism arrive abruptly amidst more mundane descriptions of weather or squabbling actors. In a sudden, peculiar flash they suggest whole worlds abutting Herzog’s, yet with utterly different codes of behavior, stores of knowledge, and interpretations of reality. In “Iquitos” a tiny boy named Modus Vivendi earns a living playing the violin at funerals. Children steal a bit of sound tape from Herzog’s crew and tie it between two trees, so tight that the wind makes it “hum and sing.” At festivals men shoot each other with bows and arrows, the recipient catching the shaft midair before it hits its mark. A large moth sits on Herzog’s dirty laundry and “feasts on the salt from [his] sweat.” In the crew’s shipment of provisions they order kilos of arrow-tip poison, which serves as local currency. “For a spoonful of this black sticky mass, you can get yourself a woman to marry, I was told in a respectful whisper by a boatman as he cleaned his toes with a screwdriver.” Such surprises exemplify the newness to Herzog’s “grammar of images”, a newness that is not simply indicative of their shock value but illustrative of a voracious curiosity about how other beings survive, and sometimes enjoy, their passage through the world.

In Conquest of the Useless, Herzog may have stumbled across the genre to which his writing is best suited. The journal form provides an inherent structure, in which seasons change, personalities clash and reconcile and clash again, and budgets dwindle. All Herzog has to do from time to time is log the current conditions of all these factors, and the drama writes itself. This single linear structure is steady and comprehensible enough to accommodate a great deal of eccentricity and divagation, and the reader never feels mired in the wash of surreal imagery and quasi-philosophic musing. With entries averaging three or four paragraphs, few feel overstuffed with detail.

When Herzog simply shows what’s there, the result is breathtaking, and even a reader unacquainted with Herzog’s work could imagine why Francois Truffaut called him “the greatest film director alive”. What spoils some of these images, however, is Herzog’s occasional habit of glossing or interpreting them for us. This can result in cringe-worthy purple prose: “In its all-encompassing, massive misery, of which it has no knowledge and no hint of a notion, the mighty jungle stood completely still for another night, which, however, true to its innermost nature, it didn’t allow to go unused for incredible destruction, incredible butchery.”

Fitting this “grammar of images” into an argument or philosophy is often misguided. Herzog’s attempts at articulating a convincing credo fail, but his rendering of the world’s strange particulars achieves the “ecstatic truth” which for him is both the aim and the content of art. Herzog scholars will perhaps read Conquest of the Useless with the goal of supplementing their understanding of his astonishing films. Doing so risks overlooking the value of Conquest as a work of art itself. The pleasures of the word are different from the pleasures of the camera. Herzog’s strange and original voice, by mediating a place and mood through language rather than footage, provides yet another new grammar by which imagination speaks.” — Laura Kolbe

“This is what “a beautiful, fresh, sunny morning” was like for Werner Herzog during the Sisyphean miseries that plagued the shooting of his Amazonian epic “Fitzcarraldo” (1982): one of two newly hatched chicks drowned in a saucer containing only a few millimeters of water. The other lost a leg and a piece of its stomach to a murderous rabbit. And Mr. Herzog realized, for the umpteenth time, that “a sense of desolation was tearing me up inside, like termites in a fallen tree trunk.”

These and other good times have been immortalized in “Conquest of the Useless,” Mr. Herzog’s journal about his best-known filmmaking nightmare. Already published in German as the evocatively titled “Eroberung des Nutzlosen” in 2004, this book, translated by Krishna Winston, seemingly recapitulates some of Les Blank’s film “Burden of Dreams,” the 1982 documentary that captured the “Fitzcarraldo” shoot in all of its magnificent, doomy glory. When he spoke to Mr. Blank, Mr. Herzog used the phrase “challenge of the impossible” to describe his heroic, arguably unhinged struggle to complete his film.

But “Burden of Dreams” never penetrated Mr. Herzog’s rogue thoughts, at least not in the way his own mesmerizingly bizarre account does. That’s understandable: Mr. Blank could concentrate on such external diversions as hauling a steamship over a hill in the Amazon rain forest, which was the pièce de résistance of Mr. Herzog’s “Fitzcarraldo” scenario.

The observations to be found in “Conquest of the Useless” are much more private and pitiless, as Mr. Herzog finds evidence of an indifferent universe wherever he turns. With the same bleak eloquence that he brings to narrating his nonfiction films (and what voice can match Mr. Herzog’s for mournfully contemplative beauty?) this book describes the exotica of the jungle. Obsessed with the bird, animal and insect worlds as a way of avoiding the human one, Mr. Herzog keeps a steady record of the perverse spectacles he encounters.

It’s always personal: fire ants rain down upon him spitefully. Hens treat him diffidently. A cobra stares him down. Amazingly Mr. Herzog becomes so emotionally involved with a “vain” albino turkey that in a moment of pique he slaps the bird “left-right with the casual elegance of the arrogant cavaliers I had seen in French Musketeer films.” Perhaps that offers some measure of just how intensely and anthropomorphically Mr. Herzog can interact with his surroundings.

Even inanimate objects (“has anyone heard rocks sigh?”) become part of the drama recollected in these pages. So a broom “is lying on the ground as if felled by an assassin.” A book leaves Mr. Herzog feeling so lonely that he buries it. No event from daybreak (“the birds were pleading for the continued existence of the Creation”) to nightfall (“the universe’s light simply burns out, and then it is gone”) is anything but fraught. In this context one man’s plan to haul a steamship overland between two rivers becomes as reasonable as anything else.

As “Conquest of the Useless” reveals, Mr. Herzog is as canny about the film world as he is about the natural one. And he knows that he needs both to sustain him. Still, he sounds happiest while living in self-imposed exile from those who control his film’s financial destiny. And he is scathing about any collaborators who do not share his love of risk-taking.

Jason Robards, originally cast in the title role, becomes an object of scorching derision because he seems fearful of the jungle. To Mr. Herzog, cowardice is a particularly despicable sin.

The book speaks bitterly about the “appalling inner emptiness” of Mr. Robards in ways that make it no surprise that Mr. Herzog soon replaces him. And “Fitzcarraldo” also loses Mick Jagger, for whom Mr. Herzog has far higher regard, once it becomes clear that making this film will take years. In a diary that spans two and a half years and details assorted calamities, Mr. Herzog eventually becomes more comfortable when his old nemesis, the tantrum-throwing madman Klaus Kinski (who starred in Mr. Herzog’s “Aguirre, the Wrath of God”) steps in.

Although “Conquest of the Useless” provides a hypnotic chronicle of the film crew’s daily progress, it inevitably heats up when Mr. Kinski arrives. No malevolent tarantula in the rain forest can match this volcanically hot-tempered actor for entertainment value. And the Kinski presence brings out the best in Mr. Herzog’s invective. Complaining constantly about his star’s divalike behavior — Mr. Herzog predicts there will be trouble when the steamship becomes more important to the film than its leading man is, and of course he’s right — Mr. Herzog is nonetheless invigorated by collaborative conflict.

Still, he perfectly understands a discreet question asked by some of the local Indians: Does Mr. Herzog want this raving, screaming, fit-pitching actor taken off his hands? In other words, should the Indians kill him? By this point in “Conquest of the Useless” that inquiry seems plausible: Mr. Herzog has described the constant deadly peril of jungle life, at one point citing the deaths of two Indians within three pages. And the loss of one shrieking blond European might not be such an aberration.

But Mr. Herzog would, as ever, prefer a surprising observation to an obvious one. He decides that the Indians must find the Herzog tenacity much scarier than the Kinski operatics.

Any book by Mr. Herzog (like “Of Walking in Ice,” his slender volume about a 1974 walk from Munich to Paris) turns his devotees into cryptographers. It is ever tempting to try to fathom his restless spirit and his determination to challenge fate. Among the oddly revealing details in “Conquest of the Useless” is Mr. Herzog’s description of the gift from him that most delighted his mother: sand, which she liked to use for scrubbing. As he suffers through the travails described in this book, he is very much his mother’s son.” — Janet Maslin

“Werner Herzog is famous for his cinematic depictions of obsessives and outsiders, from the El Dorado-seeking Spaniard played by Klaus Kinski in his 1972 international breakthrough, “Aguirre: The Wrath of God,” to Timothy Treadwell, the doomed bear-worshiper of his 2005 documentary, “Grizzly Man.” Herzog’s own reputation as an obsessive, not to mention daredevil and doomsayer, was solidified by “Burden of Dreams,” a documentary chronicling Herzog’s trials while filming “Fitzcarraldo” in the Peruvian jungle in 1981.

“Conquest of the Useless: Reflections From the Making of ‘Fitzcarraldo’ ” comprises Herzog’s diaries from the three arduous years he worked on that movie, which earned him a best director award at Cannes in 1982 yet nearly derailed his career. It reveals him to be witty, compassionate, microscopically observant and — your call — either maniacally determined or admirably persevering.

“A vision had seized hold of me…”, he writes in the book’s prologue. “It was the vision of a large steamship scaling a hill under its own steam, working its way up a steep slope in the jungle, while above this natural landscape, which shatters the weak and the strong with equal ferocity, soars the voice of Caruso.“

Around this vision Herzog fashioned a script about an aspiring rubber baron who yearns to bring opera to the Amazon, a dream requiring him to haul a steamship over a mountain from one river to another to gain access to the rubber. When Herzog meets with 20th Century Fox executives to discuss his plan, he says they envision that “a plastic model ship will be pulled over a ridge in a studio, or possibly in a botanical garden.“

“I told them the unquestioned assumption had to be a real steamship being hauled over a real mountain, though not for the sake of realism but for the stylization characteristic of grand opera,” he writes, adding, “The pleasantries we exchanged from then on wore a thin coating of frost.“

As “Burden of Dreams” made clear, “Fitzcarraldo” turned into a metaphor for itself: Herzog and his protagonist shared the same impossible goal. The jungle shoot became famous for its calamities, including Herzog’s arrest by local authorities; the departure of the original star, Jason Robards, after he fell ill with dysentery; a border war between Peru and Ecuador; plane crashes; injuries; problematic weather; and an increasingly dejected crew.

“Conquest of the Useless” fills in the gaps of that account and shows what makes Herzog so compelling as an artist, particularly in his nonfiction films: his acute fascination with people and nature.

In the city of Iquitos, he writes: “Every evening, at exactly the same minute, several hundred thousand golondrinas, a kind of swallow, come to roost for the night in the trees on the Plaza de Armas. They form black lines on the cornices of buildings. The entire square is filled with their excited fluttering and twittering. Arriving from all different directions, the swarms of birds meet in the air above the square, circling like tornados in dizzying spirals. Then, as if a whirlwind were sweeping through, they suddenly descend onto the square, darkening the sky. The young ladies put up umbrellas to shield themselves from droppings.“

The book is also filled with terrifically funny and precise renderings of the creatures that inhabit the film crew’s two jungle camps — ants, bats, tarantulas, mosquitoes, snakes, alligators, monkeys, rats, vultures, an albino turkey and an underwear-shredding ocelot. “For days a dead roach has been lying in our little shower stall, which is supplied with water from a gasoline drum on the roof,” Herzog writes in an entry dated “11 July 1979.” “The roach is so enormous in its monstrosity that it is like something that stepped out of a horror movie. It lies there all spongy, belly-up, and is so disgusting that none of us has had the nerve to get rid of it.“

He can spend a full page describing a daylong rainstorm and its aftermath, providing simple, telling details: “The tropical humidity is so intense that if you leave envelopes lying around they seal themselves.” He offers memories from his unusual early life (he grew up in a remote Bavarian mountain village) and engrossing recaps of weird stories people tell him. The effect is spellbinding.

He can be scathing — the “people in Satipo were like vomit — ugly, mean-spirited, unkempt, as if a town in the highlands had expelled its most degenerate elements and pushed them off into the jungle” — and sensitive, as when cinematographer Thomas Mauch tears open his hand and undergoes surgery without anesthesia: “I held his head and pressed it against me, and a silent wall of faces surrounded us. Mauch said he could not take any more, he was going to faint, and I told him to go ahead.” (What Herzog does next to soothe Mauch is both hilarious and moving.)

Herzog replaced Robards with Kinski, his lead from three previous films, who presented a new set of problems. As Herzog showed in his extraordinary 1999 film about Kinski, “My Best Fiend,” the guy was intolerable. Herzog is stoic in the face of Kinski’s hours of “uninterrupted ranting and raving,” calling him an “absolute pest” in an “Yves St. Laurent bush outfit.” Representatives of the Indians who serve as extras matter-of-factly offer to kill him.

Herzog, of course, isn’t exactly easygoing. He comes across as impatient and wants to do everything himself, right now. And his admiration for nature is overshadowed by his nonstop declarations about its malevolence — the sun is “murderous,” mists are “angry,” the jungle has “silent killing in its depths.” (In “Grizzly Man,” he says that “the common character of the universe is not harmony but hostility, chaos and murder,” so we know his sentiments haven’t changed.)

As the months in the jungle pass, delirium sets in. “There are widely divergent views as to what day of the month it is,” Herzog writes. The engineer hired to help guide the ship over the ridge quits. But Herzog carries on, and the tone of the diaries shifts from dreamy to nightmarish: “No one’s on my side anymore, not one person, not one single person. In the midst of hundreds of Indian extras, dozens of woodsmen, boatmen, kitchen personnel, the technical team, and the actors, solitude flailed at me like a huge enraged animal.“

For decades Herzog has declared his resistance to introspection; he claims not to know the color of his eyes, since he detests looking into mirrors, and is outspoken about his contempt for psychoanalysis. So his vulnerability here is noteworthy. “At night I’m even lonelier than during the day,” he writes. “I listened intently to the silence, pierced by tormented insects and tormented animals. Even the motors of our boats have something tormented about them.“

It’s hard to know how to read such hyperbolic sentiments, especially given his dry wit. When, after months of trying, he finally gets the ship over the ridge, bringing “Fitzcarraldo” near completion, how does he feel? The book’s sardonic title says it all.”

00:20 Publié dans Cinéma | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : cinéma, werner herzog, klaus kinski, allemagne, film, 7ème art |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les commentaires sont fermés.