The Assassination of Pyotr Stolypin

From Solzhenitsyn's "200 Hundred Years Together"

What are we to do with this disaster? Let pious Jews pray intensely to God, that He set Russia’s fate in the hands of religious and also sensible and brave men, who would want and could dare to do good for both peoples2.

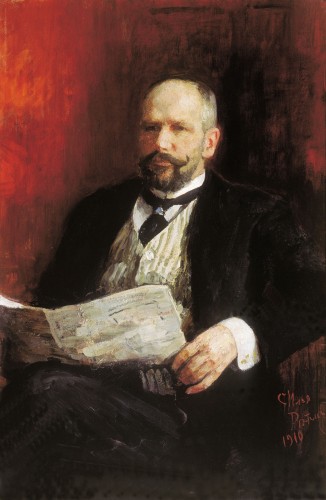

Such a man would be granted to Russia, if only for a time. As the Romanovs’ empire was swept into a ruinous war with Japan and the 1905 Revolution, Pyotr Arkadievich Stolypin would stand against the maelstrom. Stolypin was ruthlessly suppressing rebellion as governor of Saratov oblast when he was called by Nicholas II to national duty. Within months, the new prime minister would proceed to re-establish order in Russia and undertake challenging political, economic and agricultural reforms. Just as Soloviev had hoped but would never see, Stolypin also attempted to improve the acrimonious Russian-Jewish relationship at the level of nationalities policy. This premature effort, however, was unlikely to satisfy any interested party, much less radicals of any persuasion.

Stolypin would resign in March of 1911 from the fractious and chaotic Duma after the failure of his land-reform bill. His peace in this world would be short-lived, though; he was assassinated at the Kiev Opera House on September 14in the presence of the emperor. Upon being shot, Stolypin stood and declared his willingness to die for the Tsar, whom he then blessed before collapsing. In a eulogy for the fallen, the conservative monarchist Lev Tikhomirov would praise his nobility and strength of heart, all of which he devoted to the service of his fatherland:

The blood of his ancestors spoke in him, and his soul was deeply Russian and Christian. He believed in God as the Lord may grant belief to the servants before His altar…In such a way did he believe in Russia, and in this we can only admire him. And from this faith he drew vast power3.

Stolypin’s killer was 24-year-old Dmitry Bogrov (Mordechai Gershkovich), a leftist revolutionary who had also moonlighted as a provocateur for the Okhrana, Imperial Russia’s secret police. The otherwise unremarkable Bogrov harbored a burning animosity toward the autocracy, and as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn will show in the following passage, his sentiments were shared at the time by many other Russian Jews. With moral, political and financial support from the Diaspora (especially in America), the Jewish community was radicalizing to unprecedented degrees, and Russians were bristling back. There would be no reduction of inter-ethnic tensions. Bogrov acted “extravagantly,” as he put it, to prevent Stolypin from instigating pogroms, but in doing so he murdered perhaps the one man capable of implementing some measure of a just peace between Russians and Jews4.Too often in history the victim narrative is a convenient pretext for aggression. Chauvinism and hatred cut both ways, and the atrocities they inspire can wreak consequences far beyond what their initiators might have imagined.

Pytor Stolypin may well have been mistaken in the formulation of key policies. Tikhomirov had earlier criticized the prime minister for his adherence to a failed Western-style parliamentarianism, and urged him to first uphold the integrity of the Great Russian ethnos and its culture before tackling any other “national questions” within the empire. It would be better, said Tikhomirov, that subject peoples prove themselves worthy of the rights bestowed them by the Tsar.

Yet Stolypin was also an adept statesman with unmatched force of will. Had he eluded his assassin’s bullet, he quite possibly could have guided Russia intact past the next catastrophic round of war and revolution that awaited her. In his work 200 Years Together, Solzhenitsyn dedicates considerable space to Stolypin’s death and its implications. Step by terrible step, the drama unfolds as his murder at the Kiev opera will facilitate revolutionary tyranny over Russia. The curtain only descends upon our witness to the most “extravagant” effect of Bogrov’s exploit, the enslavement and near-extermination of both Jewry and the Slavic tribes.

***

Text taken from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s 200 Years Together, Chapter 10: In the Time of the Duma (pp.462-467).

Translated from Russian by Mark Hackard.

The first Russian premier who faithfully set and carried out the task of Jewish equal status, despite the will of the Tsar, died—was this History’s mockery?—at the hands of a Jew…

There had already been seven attempts to kill Stolypin by entire revolutionary groups of varied composition; none had succeeded. And then a loner would ingeniously manage it.

Still young and of immature mind, Bogrov himself could not grasp in full Stolypin’s public significance. But from childhood he had seen the everyday degrading sides of political inequality and was inflamed, for his family, colleagues and himself, to hatred of the Tsarist power. And clearly in Kiev’s ideologically progressive Jewish circles, there would be no softening toward Stolypin for his attempts to remove anti-Jewish restrictions. Among the well-off, the scales were tipped by memory of his energetic suppression of the 1905 Revolution and displeasure over his efforts toward the “nationalization of Russian credit,” i.e. open competition with private capital. Among groups of Kievan Jewry (and those of Petersburg, which the future killer also frequented), was active the ultra-radical Field, where the young Bogrov considered himself right and even obligated to kill Stolypin.

So strong was the Field that it permitted such an arrangement: the capitalist father Bogrov ascends and prospers under the monarchical system, while Bogrov the son commits to the destruction of that system. And the father, after the assassination, expresses pride in such a son. It turns out that Bogrov wasn’t so alone: he was quietly applauded by those in well-to-do quarters, those who had earlier remained unconditionally loyal to the regime.

And the gunshot that struck down Russia’s recovery could have been directed against the Tsar. But Bogrov thought killing the Tsar impossible, because (in his words) “this could have provoked persecution of the Jews” and “brought about constraints on their rights.” By murdering only the prime minister, he foresaw correctly that such a thing wouldn’t happen. Yet he thought—and was bitterly mistaken—that this act would favorably serve the fate of Russian Jewry…

And what happened in “Black Hundred Kiev,” populated by a great number of Jews? Among Kievan Jews in the very first hours after the murder, there arose a mass panic, and a movement to abandon the city began. “Terror seized the Jewish population not only of Kiev, but also of the most remote localities of the pale of settlement and inner Russia."5 A club of Russian nationalists sought to collect signatures to deport all Jews from Kiev. (It wanted to collect them, but didn’t.) There came to pass not the slightest attempt at a pogrom. The chairman of the youth organization “Double Eagle” Golubiev called for the storm of the Kiev Okhrana section that failed to stop the assassination and for beatings of Jews; he was reined in immediately.

The newly sworn-in prime minister Kokovtsov at once called Cossack regiments into the city (all these forces were on maneuvers and far away) and sent all governors an energetic telegram: prevent pogroms by all means, including force. Units were deployed to an extent not done against the revolution. (Slizoberg: If pogroms broke out in September 1911, “Kiev would have witnessed a slaughter not seen since the times of Khmelnitsky."6)

And not a pogrom took place in Russia, not one, not in the least. (Although we often read dense volumes how the Tsarist government dreamt only of arranging Jewish pogroms and was always seeking a way to do so.)

It stands to reason that the prevention of disorder is a direct duty of the state, and in successfully carrying out this task, awaiting praise would be inappropriate. But after such a shocking event and on such grounds—the murder of the prime minister!—the avoidance of expected pogroms could be noted, even if in passing. But no—no one heard that intonation, and no one mentions that.

And what’s even difficult to believe—Kiev’s Jewish community did not issue a denunciation or an indirect expression of sorrow over the murder. Just the opposite—after Bogrov’s execution many Jewish students, male and female, brazenly dressed in mourning.

Russians at the time noticed this. It has now been published that in December 1912 Vasily Rozanov wrote: “After [the murder of] Stolypin, I’ve somehow broken with them [the Jews]: as if a Russian would dare kill a Rothschild and more broadly one of their great men.”7

From the historical viewpoint there come two substantial thoughts on why it would be folly to write off Bogrov’s deed as the “action of internationalist forces.” The first and central of these: it wasn’t so. Not only Bogrov’s brother in his book, but also various neutral sources point out that he had reckoned to assist Jewry’s fortunes.8 The second thought: to take up what is inconvenient in history, to think it over and to regret is responsible, while to disavow a matter and wash one’s hands of it is shallow.

However, the disavowals and hand-wringing began almost immediately. In October of 1911, the Octobrist faction requested an inquiry on the murky circumstances of Stolypin’s murder. And at that moment parliamentary deputy Nisselovich protested: why did the Octobrists not conceal in their request that Bogrov was a Jew?! That, he said, was anti-Semitism!

I’ve also become familiar with this incomparable argument. After 70 years I received it from the American Jewish community in the form of a most severe accusation: why did I not conceal, why did I also say that Stolypin’s killer was a Jew? It does not matter that I described him as fully as I could. And it wasn’t important what his Jewish identity meant in his motives. No, non-concealment on my part—this was anti-Semitism!!

Deputy Guchkov with integrity would answer at the time:

“I think that a much greater act of anti-Semitism lies in Bogrov’s very action. I’d propose to State Duma member Nisselovich that he addresses his ardent words of admonition not to us, but to his co-religionists. Let him convince them with the power of his oratory to stay further away from two shameful professions: service as informants in the Okhrana and service as agents of terror. By this he would render a much greater service to his tribe.9"

But what is that worth to Jewish memory when Russian history has permitted this assassination to be wiped clear of its memory? It has remained some insignificant, collateral blemish. Only in the 1980s did I begin to raise it from oblivion, and for 70 years it was unacceptable to remember that murder.

As the decades recede, more events and their meanings become visible to us. I’ve often fallen to thinking over the capriciousness of History and the unforeseen consequences it visits upon us, the consequences of our actions.

-

Wilhelmine Germany loosed Lenin upon Russia to demoralize her; 28 years later Germany would be divided for a half-century.

-

Poland would facilitate the strengthening of the Bolsheviks in their most difficult 1919 for a quick defeat of the Whites—and received in return 1939, 1944, 1956 and 1980.

-

How zealously Finland would help the Russian revolutionaries, and how she could not abide her advantageous liberty as a component of Russia. She received from the Bolsheviks 40 years of political debasement (“Finlandization”).

-

England in 1914 thought to crush Germany as a global competitor, but tore itself from the ranks of the great powers as all of Europe was crushed.

-

The Cossacks in Petrograd were neutral in February and October [1917], and in a year in a half would reap their own genocide (and many were even those very Cossacks).

-

In the first days of June 1917, the Left Social Revolutionaries gravitated to the Bolsheviks and gave them the outward appearance of a “coalition” and a widened platform. A year later they were squashed in a way that no autocracy could have managed.

Foresight of these long-term consequences is never granted to us or anyone. And the only salvation from such blunders is to be guided by the compass of God’s morality. Or in simple folk-language: “Don’t lay traps for others—you’ll fall into them.”

So it was with the murder of Stolypin—Russia endured brutal suffering, but Bogrov didn’t help the Jews. However others may see it, it is here I sense the gigantic steps of History, the results striking in their unexpectedness. Safeguarding Kiev’s Jews from persecution, Bogrov killed Stolypin. Had he survived, Stolypin would soon have been dismissed by the Tsar, but without question would have been called again into the leaderless musical chairs of 1914-16. Under him, Russia would not have come to such a shameful end, neither in the war nor in the Revolution. (If we would have even entered that war under him.)

Step 1: A murdered Stolypin meant shot nerves in the war, and Russia fell under the jackboots of the Bolsheviks.

Step 2: The Bolsheviks, for all their savagery, turned out to be even more incompetent than the Tsarist government, and in a quarter-century would quickly give away half-Russia to the Germans, including Kiev.

Step 3: Hitler’s forces easily entered Kiev and then destroyed the city’s Jewry.

The same Kiev, also in September, and only 30 years after Bogrov’s gun blast.

_____________

Notes

1 -- Toward the end of his life, Soloviev would come to repudiate his hopes for a free theocratic state. His last work, A Short Tale of Antichrist, reflects his disillusionment with the possibility of a perfected temporal order. Soloviev models the Antichrist’s earthly kingdom upon his earlier ideal.

2 -- Mochulsky, Konstantin. Gogol, Soloviev, Dostoevsky. Respublika. Moscow, 1995.

3 -- Tikhomirov, Lev. “U Mogily Petra Stolypina”. Moskovskie Vedomosti. 1911. No. 207

4 -- During the Second World War, Orthodox theologian Father Sergei Bulgakov wrote on the world-historical struggle between Judaism and Christendom: “Israel’s form in this state is fateful and terrible. On the one hand, it is persecuted namely by Christian peoples, and this persecution takes from time to time cruel and ferocious forms- oppression and hate to the point of extermination; such are Jewish pogroms to this day. On the other hand, Israel itself remains the overt or hidden persecutor of Christ and Christendom to the point to its direct and dire oppression, as in Russia.” In accordance with Church tradition, the tragedy will only be resolved at the end of time with Christ’s Second Coming, when through a holy remnant “all Israel shall be saved” (Romans XI: 26).

5 -- G.B. Slizoberg, Volume III, p. 249

6 --G.B. Slizoberg, Volume III, p. 249

7 -- “Correspondence of V.V. Rozanov and M.O. Gershenzon”. Novyi Mir, No. 3, p. 232

8 -- Bogrov, Vladimir. Dmitry Bogrov and the Murder of Stolypin: Exposing Secrets True and False. Berlin, 1931.

9 -- A. Guchkov. Speech in the State Duma on 15th October 1911 [inquiry into the murder of Chairman of Council of Ministers P.A. Stolypin] // A. Guchkov in the Third State Duma (1907-1912): Collection of Speeches. St. Petersburg, 1912, p. 163

After a series of pogroms tore through Russia in 1886, the young philosopher Vladimir Soloviev would exercise his prophetic impulse. Neither a slave to social fashions nor a stranger to controversy, Soloviev was a friend to the Jews out of sincerity rather than any calculation. Two years prior, he had published an article asserting the intertwined destinies of Christendom and Jewry as part of his greater vision of a “free theocracy.”1And so in the pogroms’ aftermath, Soloviev wrote in a letter to his acquaintance, the Talmudic scholar Feivel Getz:

After a series of pogroms tore through Russia in 1886, the young philosopher Vladimir Soloviev would exercise his prophetic impulse. Neither a slave to social fashions nor a stranger to controversy, Soloviev was a friend to the Jews out of sincerity rather than any calculation. Two years prior, he had published an article asserting the intertwined destinies of Christendom and Jewry as part of his greater vision of a “free theocracy.”1And so in the pogroms’ aftermath, Soloviev wrote in a letter to his acquaintance, the Talmudic scholar Feivel Getz:

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.