mardi, 17 avril 2012

Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing, RIP

PAUL GOTTFRIED is the Raffensperger Professor of Humanities at Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania.

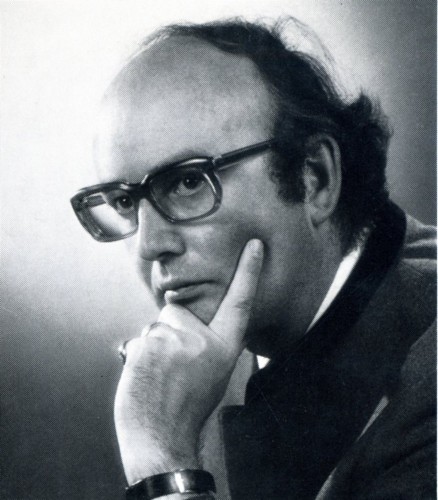

The death of Caspar von Schrenck- Notzing on January 25, 2009, brought an end to the career of one of the most insightful German political thinkers of his generation. Although perhaps not as well known as other figures associated with the postwar intellectual Right, Schrenck- Notzing displayed a critical honesty, combined with an elegant prose style, which made him stand out among his contemporaries. A descendant of Bavarian Protestant nobility who had been knights of the Holy Roman Empire, Freiherr von Schrenck- Notzing was preceded by an illustrious grandfather, Albert von Schrenck-Notzing, who had been a close friend of the author Thomas Mann. While that grandfather became famous as an exponent of parapsychology, and the other grandfather, Ludwig Ganghofer, as a novelist, Caspar turned his inherited flair for language toward political analysis.

Perhaps he will best be remembered as the editor of the journal Criticón, which he founded in 1970, and which was destined to become the most widely read and respected theoretical organ of the German Right in the 1970s and 1980s. In the pages of Criticón an entire generation of non-leftist German intellectuals found an outlet for their ideas; and such academic figures as Robert Spämann, Günter Rohrmöser, and Odo Marquard became public voices beyond the closed world of philosophical theory. In his signature editorials, Criticón's editor raked over the coals the center-conservative coalition of the Christian Democratic (CDU) and the Christian Social (CSU) parties, which for long periods formed the postwar governments of West Germany.

Despite the CDU/CSU promise of a "turn toward the traditional Right," the hoped-for "Wende nach rechts" never seemed to occur, and Helmut Kohl's ascent to power in the 1980s convinced Schrenck- Notzing that not much good could come from the party governments of the Federal Republic for those with his own political leanings. In 1998 the aging theorist gave up the editorship of Criticón, and he handed over the helm of the publication to advocates of a market economy. Although Schrenck-Notzing did not entirely oppose this new direction, as a German traditionalist he was certainly less hostile to the state as an institution than were Criticón's new editors.

But clearly, during the last ten years of his life, Schrenck-Notzing had lost a sense of urgency about the need for a magazine stressing current events. He decided to devote his remaining energy to a more theoretical task—that of understanding the defective nature of postwar German conservatism. The title of an anthology to which he contributed his own study and also edited, Die kupierte Alternative (The Truncated Alternative), indicated where Schrenck-Notzing saw the deficiencies of the postwar German Right. As a younger German conservative historian, Karl- Heinz Weissmann, echoing Schrenck- Notzing, has observed, one cannot create a sustainable and authentic Right on the basis of "democratic values." One needs a living past to do so. An encyclopedia of conservatism edited by Schrenck-Notzing that appeared in 1996 provides portraits of German statesmen and thinkers whom the editor clearly admired. Needless to say, not even one of those subjects was alive at the time of the encyclopedia's publication.

What allows a significant force against the Left to become effective, according to Schrenck-Notzing, is the continuity of nations and inherited social authorities. In the German case, devotion to a Basic Law promulgated in 1947 and really imposed on a defeated and demoralized country by its conquerors could not replace historical structures and national cohesion. Although Schrenck-Notzing published opinions in his journal that were more enthusiastic than his own about the reconstructed Germany of the postwar years, he never shared such "constitutional patriotism." He never deviated from his understanding of why the post-war German Right had become an increasingly empty opposition to the German Left: it had arisen in a confused and humiliated society, and it drew its strength from the values that its occupiers had given it and from its prolonged submission to American political interests. Schrenck-Notzing continually called attention to the need for respect for one's own nation as the necessary basis for a viable traditionalism. Long before it was evident to most, he predicted that the worship of the postwar German Basic Law and its "democratic" values would not only fail to produce a "conservative" philosophy in Germany; he also fully grasped that this orientation would be a mere transition to an anti-national, leftist political culture. What happened to Germany after 1968 was for him already implicit in the "constitutional patriotism" that treated German history as an unrelieved horror up until the moment of the Allied occupation.

For many years Schrenck-Notzing had published books highlighting the special problems of post-war German society and its inability to configure a Right that could contain these problems. In 2000 he added to his already daunting publishing tasks the creation and maintenance of an institute, the Förderstiftung Konservative Bildung und Forschung, which was established to examine theoretical conservative themes. With his able assistant Dr. Harald Bergbauer and the promotional work of the chairman of the institute's board, Dieter Stein, who also edits the German weekly, Junge Freiheit, Schrenck-Notzing applied himself to studies that neither here nor in Germany have elicited much support. As Schrenck-Notzing pointed out, the study of the opposite of whatever the Left mutates into is never particularly profitable, because those whom he called "the future-makers" are invariably in seats of power. And nowhere was this truer than in Germany, whose postwar government was imposed precisely to dismantle the traditional Right, understood as the "source" of Nazism and "Prussianism." The Allies not only demonized the Third Reich, according to Schrenck-Notzing, but went out of their way, until the onset of the Cold War, to marginalize anything in German history and culture that was not associated with the Left, if not with outright communism.

This was the theme of Schrenck-Notzing's most famous book, Charakterwäsche: Die Politik der amerikanischen Umerziehung in Deutschland, a study of the intent and effects of American re-education policies during the occupation of Germany. This provocative book appeared in three separate editions. While the first edition, in 1965, was widely reviewed and critically acclaimed, by the time the third edition was released by Leopold Stocker Verlag in 2004, its author seemed to be tilting at windmills. Everything he castigated in his book had come to pass in the current German society—and in such a repressive, anti-German form that it is doubtful that the author thirty years earlier would have been able to conceive of his worst nightmares coming to life to such a degree. In his book, Schrenck-Notzing documents the mixture of spiteful vengeance and leftist utopianism that had shaped the Allies' forced re-education of the Germans, and he makes it clear that the only things that slowed down this experiment were the victories of the anticommunist Republicans in U.S. elections and the necessities of the Cold War. Neither development had been foreseen when the plan was put into operation immediately after the war.

Charakterwäsche documents the degree to which social psychologists and "antifascist" social engineers were given a free hand in reconstructing postwar German "political culture." Although the first edition was published before the anti-national and anti-anticommunist German Left had taken full power, the book shows the likelihood that such elements would soon rise to political power, seeing that they had already ensconced themselves in the media and the university. For anyone but a hardened German-hater, it is hard to finish this book without snorting in disgust at any attempt to portray Germany's re-education as a "necessary precondition" for a free society.

What might have happened without such a drastic, punitive intervention? It is highly doubtful that the postwar Germans would have placed rabid Nazis back in power. The country had had a parliamentary tradition and a large, prosperous bourgeoisie since the early nineteenth century, and the leaders of the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats, who took over after the occupation, all had ties to the pre-Nazi German state. To the extent that postwar Germany did not look like its present leftist version, it was only because it took about a generation before the work of the re-educators could bear its full fruit. In due course, their efforts did accomplish what Schrenck-Notzing claimed they would—turning the Germans into a masochistic, self-hating people who would lose any capacity for collective self-respect. Germany's present pampering of Muslim terrorists, its utter lack of what we in the U.S. until recently would have recognized as academic freedom, the compulsion felt by German leaders to denigrate all of German history before 1945, and the freedom with which "antifascist" mobs close down insufficiently leftist or anti-national lectures and discussions are all directly related to the process of German re-education under Allied control.

Exposure to Schrenck-Notzing's magnum opus was, for me, a defining moment in understanding the present age. By the time I wrote The Strange Death of Marxism in 2005, his image of postwar Germany had become my image of the post-Marxist Left. The brain-snatchers we had set loose on a hated former enemy had come back to subdue the entire Western world. The battle waged by American re-educators against "the surreptitious traces" of fascist ideology among the German Christian bourgeoisie had become the opening shots in the crusade for political correctness. Except for the detention camps and the beating of prisoners that were part of the occupation scene, the attempt to create a "prejudice-free" society by laundering brains has continued down to the present. Schrenck-Notzing revealed the model that therapeutic liberators would apply at home, once they had fi nished with Central Europeans. Significantly, their achievement in Germany was so great that it continues to gain momentum in Western Europe (and not only in Germany) with each passing generation.

The publication Unsere Agenda, which Schrenck-Notzing's institute published (on a shoestring) between 2004 and 2008, devoted considerable space to the American Old Right and especially to the paleoconservatives. One drew the sense from reading it that Schrenck-Notzing and his colleague Bergbauer felt an affinity for American critics of late modernity, an admiration that vastly exceeded the political and media significance of the groups they examined. At our meetings he spoke favorably about the young thinkers from ISI whom he had met in Europe and at a particular gathering of the Philadelphia Society. These were the Americans with whom he resonated and with whom he was hoping to establish a long-term relationship. It is therefore fitting that his accomplishments be noted in the pages of Modern Age. Unfortunately, it is by no means clear that the critical analysis he provided will have any effect in today's German society. The reasons are the ones that Schrenck-Notzing gave in his monumental work on German re-education. The postwar re-educators did their work too well to allow the Germans to become a normal nation again.

00:05 Publié dans Hommages, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : conservatisme, allemagne, caspar von schrenck notzing, hommage, criticon, révolution conservatrice, droite |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les commentaires sont fermés.