Par Alastair Crooke

Source Strategic culture

Il y a deux semaines, nous écrivions sur la façon dont la politique étrangère du président Trump s’était en quelque sorte « transmutée » en un « néo-américanisme », et nous avions cité l’expert concernant les affaires étrangères états-uniennes, Russell-Mead, qui suggérait que la métamorphose du 8 mai de Trump (la sortie de l’accord iranien), représentait quelque chose de nouveau, un changement de direction (abandonnant son style d’âpre négociateur), pour adhérer à – selon les termes de Russell-Mead – « une ère néo-américaine dans la politique mondiale – plutôt qu’une ère post-américaine [de style d’Obama] ». « L’administration veut élargir le pouvoir américain, plutôt que s’adapter à son déclin (comme l’aurait fait Obama). Pour l’instant, le Moyen-Orient est la pièce maîtresse de cette nouvelle tendance ». Russell-Mead explique que cette nouvelle direction prise par Trump provient de « son instinct (celui de Trump) lui disant que la plupart des Américains sont tout sauf avides d’un monde ‘post-américain’. Les partisans de M. Trump ne veulent pas de longues guerres, mais ils ne sont pas prêts non plus à une acceptation stoïque du déclin national ».

Il y a là quelque chose de paradoxal : Trump et sa base déplorent le coût de l’engagement dans cet immense parapluie de défense américaine, disséminée dans le monde entier par les mondialistes (sentiments aggravés par l’ingratitude supposée de ses bénéficiaires) – mais le Président veut « élargir le pouvoir américain, plutôt que de s’adapter à son déclin ». C’est-à-dire qu’il veut plus de pouvoir, mais moins d’empire. Comment pourrait-il résoudre cette quadrature du cercle ?

Eh bien une indication est apparue presque un an plus tôt lorsque, le 29 juin 2017, le Président a utilisé un mot tout à fait inattendu lors d’un discours donné à une conférence du département de l’énergie intitulée : « Libérer l’énergie américaine ». Au lieu de parler de l’indépendance énergétique américaine, comme on pouvait s’y attendre, il a plutôt annoncé une nouvelle ère de « dominance » énergétique américaine.

Dans un discours « qui cherchait à souligner une rupture avec les politiques de Barack Obama », note le Financial Times, « M. Trump a lié l’énergie à son programme America First… », « La vérité est que nous avons maintenant des réserves d’énergie presque illimitées dans notre pays », a déclaré M. Trump. « Nous sommes vraiment aux commandes, et vous savez quoi : nous ne voulons pas que d’autres pays nous enlèvent notre souveraineté et nous disent quoi faire et comment le faire. Ça n’arrivera pas. Avec ces ressources incroyables, mon administration recherchera non seulement l’indépendance énergétique américaine que nous recherchons depuis si longtemps, mais aussi la dominance énergétique américaine. ».

Il semble, comme l’explique Chris Cook, que Gary Cohn, alors conseiller économique du Président, ait joué un rôle dans la genèse de cette ambition. Cohn (alors chez Goldman Sachs) a conçu en 2000, avec un collègue de chez Morgan Stanley, un plan pour prendre le contrôle du marché mondial du pétrole par le biais d’une plateforme de trading électronique, basée à New York. En bref, les grandes banques ont attiré d’énormes quantités d’argent (provenant de fonds spéculatifs, par exemple), vers ce marché, pour parier sur les prix futurs (sans qu’elles ne prennent jamais réellement livraison de pétrole brut : le commerce de « pétrole papier », plutôt que de pétrole physique). En même temps, ces banques travaillaient en collusion avec les principaux producteurs de pétrole (y compris, plus tard, l’Arabie saoudite) pour préacheter du pétrole physique de telle manière que, en retenant ou en libérant du brut physique sur le marché, les grandes banques de New York pouvaient « influencer » les prix (en créant une pénurie ou une surabondance).

Pour donner un ordre d’idée de la capacité de ces banquiers à « influencer » les prix, au milieu de 2008, on estimait que quelque 260 milliards de dollars d’investissements « gérés » (spéculatifs) étaient en jeu sur les marchés de l’énergie, éclipsant complètement la valeur du pétrole qui sort effectivement de la mer du Nord chaque mois, peut-être de 4 à 5 milliards de dollars, tout au plus. Ces jeux d’options pétrolières « papier » l’emporteraient donc souvent sur les « fondamentaux » de l’offre réelle et de la demande réelle par l’utilisateur final.

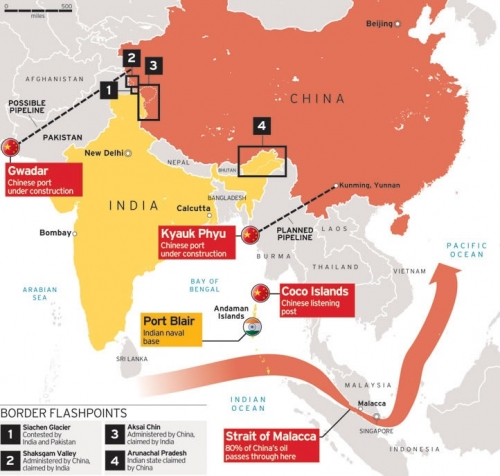

Pour Cohn, la première étape consistait donc, pour les États-Unis, à gérer ce marché commercial, à la fois en termes de prix et d’accès, les antagonistes américains tels que l’Iran ou la Russie pouvant accéder au marché à des conditions inférieures, voire pas du tout. La « deuxième étape » présumée a été de pousser la production américaine de schistes, de construire de nouveaux terminaux américains d’exportation de GNL et d’ouvrir l’Amérique à la poursuite de l’exploration pétrolière et gazière, tout en forçant tout le monde, de l’Allemagne à la Corée du Sud et à la Chine, à acheter des exportations américaines de GNL. Et troisièmement, avec les exportations de pétrole du Golfe déjà sous l’égide des États-Unis, restaient alors deux grands producteurs d’énergie du Moyen-Orient au-delà des frontières de l’« influence » du cartel (tombant davantage dans le « cœur » stratégique producteur d’énergie de la Russie rivale) : l’Iran – qui fait maintenant l’objet d’une tentative de changement de régime et d’un blocus économique sur ses exportations de pétrole, et l’Irak, qui fait l’objet d’intenses (mais douces) pressions politiques (comme la menace de sanctionner l’Irak en vertu de la loi dite Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act) pour forcer son adhésion à la sphère occidentale.

Que signifie donc cette notion « trumpienne » de dominance énergétique dans un langage simple ? Les États-Unis – si cette dominance énergétique réussissait − contrôleraient simplement le robinet du développement économique – ou son absence – pour des rivaux comme la Chine et le reste de l’Asie. Et les États-Unis pourraient diminuer les revenus de la Russie de cette façon aussi. En bref, les États-Unis pourraient mettre un frein aux plans de développement économique de la Chine et de la Russie. Est-ce la raison pour laquelle les accords avec l’Iran ont été révoqués par le Président Trump ?

Voici donc la quadrature du cercle (plus de puissance américaine, mais moins d’empire) : les objectifs américains de Trump pour la « dominance », non pas par le biais de l’infrastructure permanente des globalistes de la défense américaine, mais par l’effet de levier intelligent du dollar américain et du monopole de compensation financière, par la protection et le maintien de la supériorité technologique américaine, et par la domination du marché de l’énergie, qui à son tour représente le robinet marche/arrêt de la croissance économique pour les rivaux américains. De cette façon, Trump peut « ramener les troupes à la maison », tout en faisant que l’Amérique garde son hégémonie. Le conflit militaire ne servant plus qu’en dernier recours.

Le conseiller principal Peter Navarro déclarait cette semaine sur NPR que « nous pouvons les empêcher [les Chinois] de mettre nos entreprises de haute technologie hors service ‘et’ d’acheter nos joyaux technologiques …. Chaque fois que nous innovons, la Chine vient l’acheter ou le voler. »

Est-ce le plan de Trump : par la domination du marché et la guerre commerciale, prolonger la « supériorité » de l’Amérique en matière de technologie, de finance et d’énergie – et ne pas être obligée d’une manière ou d’une autre de s’adapter au déclin ? Et en agissant de la sorte, réduire – ou du moins retarder – l’émergence de rivaux ? Dans ce contexte, deux questions se posent immédiatement : cette formule est-elle l’adoption d’un néo-conservatisme, par l’administration américaine, que la propre base de Trump déteste tant ? Et, deuxièmement, cette approche peut-elle fonctionner ?

Il ne s’agit peut-être pas de néo-conservatisme, mais plutôt de retravailler un ancien thème. Les néo-conservateurs américains voulaient surtout utiliser un marteau contre les parties du monde qu’ils n’aimaient pas ; et le remplacer par quelque chose qu’ils voulaient. La méthode de Trump est plus machiavélique dans sa forme.

Les racines de ces deux courants de pensée résident cependant – en grande partie – dans l’influence de Carl Schmitt sur la pensée conservatrice américaine par l’intermédiaire de son ami Leo Strauss, à Chicago (que Trump ait lu ou pas l’un ou l’autre penseur, les idées circulent toujours dans l’éther américain). Schmitt soutenait que la politique (contrairement à la pensée libérale/humaniste) n’a rien à voir avec l’équité ou la justice dans le monde – c’est-à-dire le travail des moralistes et des théologiens – la politique, pour Schmitt, concerne le pouvoir et la survie politique, et rien de plus.

Les libéraux (et les globalistes), suggérait Schmitt, ont du mal à utiliser le pouvoir pour écraser les forces alternatives qui émergent : leur vision optimiste de la nature humaine les amène à croire en la possibilité de médiation et de compromis. L’optique schmittienne rejetait comme dérisoire l’opinion libérale et mettait l’accent sur le rôle du pouvoir, pur et simple – basé sur une compréhension plus sombre de la vraie nature des « autres » et des rivaux. Ce point semble être la racine de la pensée de Trump : Obama et les « libéraux »étaient prêts à échanger les « joyaux de la couronne » de « Notre culture »(expertise financière, technologique et énergétique) par le biais d’« actions positives » multilatérales qui aideraient les États moins développés (comme la Chine). C’est peut-être la raison pour laquelle Trump s’est retiré de l’Accord sur le climat : pourquoi aider des rivaux potentiels, tout en imposant des handicaps volontaires à sa propre culture ?

C’est sur ce dernier point commun, assez étroit (l’impératif de garder le pouvoir américain intact), que les néo-conservateurs et les trumpistes, s’unissent : et tous deux partagent aussi leur mépris pour les libéraux utopiques qui gaspilleraient les joyaux de la culture occidentale – pour de soi-disant idéaux humanitaires – et permettraient aux rivaux déterminés de l’Amérique de se dresser pour renverser l’Amérique et sa culture (selon leur point de vue).

Le terrain d’entente entre ces deux courants s’exprime avec une candeur remarquable à travers le commentaire de Berlusconi selon lequel « nous devons être conscients de la supériorité de notre civilisation [occidentale] ». Steve Bannon dit quelque chose de très similaire, bien qu’exprimée sous la forme de la préservation d’une culture judéo-chrétienne occidentale (menacée).

Ce sens de l’avantage culturel qui doit à tout prix être récupéré et préservé explique peut-être un peu (mais pas totalement) l’ardent soutien de Trump envers Israël : s’adressant à la Channel Two israélienne, Richard Spencer, un leader éminent de l’Alt-Right américain (et une composante de la base de Trump), soulignait le sentiment profond de dépossession des Blancs, dans leur propre pays [les États-Unis] :

« …. un citoyen israélien, quelqu’un qui comprend votre identité, qui a le sentiment d’être une nation et un peuple, ainsi que l’histoire et l’expérience du peuple juif, vous devriez respecter quelqu’un comme moi, qui a des sentiments analogues à l’égard des Blancs. Vous pourriez dire que je suis un sioniste blanc – dans le sens où je me soucie de mon peuple, je veux que nous ayons une patrie sûre pour nous tous et pour nous-mêmes. Tout comme vous voulez une patrie sûre en Israël. »

Ainsi, la tentative d’exploiter et d’utiliser comme une arme la culture élitiste américaine – par le dollar, l’hégémonie supposée dans le domaine de l’énergie et son emprise sur le transfert de technologie − peut-elle réussir à faire perdurer la « culture » américaine (selon la vision réductionniste de la base électorale de Trump) ? C’est la question à soixante-quatre mille dollars, comme on dit. Cela peut facilement provoquer une réaction tout aussi puissante ; et beaucoup de choses peuvent se produire au niveau national aux États-Unis, entre aujourd’hui et les élections de mi-mandat de novembre, qui pourraient soit confirmer le pouvoir du président – soit le défaire. Il est difficile de faire une analyse au-delà de cet horizon.

Mais un point plus important est que si Trump se passionne pour la culture américaine et l’hégémonie, les dirigeants non occidentaux d’aujourd’hui ressentent tout aussi fortement qu’il est temps pour « le siècle américain » de céder la place. Tout comme après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, les anciens États coloniaux voulaient l’indépendance, les dirigeants d’aujourd’hui veulent la fin du monopole du dollar, ils veulent la fin de l’ordre mondial dirigé par les États-Unis et de ses institutions dites « internationales » ; ils veulent « exister » selon leur culture propre et ils veulent retrouver leur souveraineté. Il ne s’agit pas seulement d’un nationalisme culturel et économique, mais d’un point d’inflexion significatif − loin de l’économie néolibérale, de l’individualisme et du mercantilisme brut – vers une expérience humaine plus complète.

La marée, dans le sillage de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, était certainement irréversible à l’époque. Je me souviens même que les anciens colonialistes européens ont ensuite déploré leur retrait forcé : « Ils vont [les anciennes colonies] le regretter », prédisaient-ils avec confiance. (Non, ce ne fut jamais le cas.) La marée d’aujourd’hui est tout aussi forte et s’est même étendue à l’Europe. Qui sait si les Européens auront la force de repousser les machinations financières et commerciales de Trump ? Ce sera un test important pour la suite.

Mais ce qui est différent aujourd’hui (par rapport à l’époque), c’est que l’hégémonie monétaire, les prouesses technologiques et la « dominance »énergétique ne sont plus du tout des possessions assurées de l’Occident. Elles ont commencé à changer de mains, il y a déjà quelque temps.

Alastair Crooke

Traduit par Wayan, relu par Cat pour le Saker Francophone.

http://lesakerfrancophone.fr/quest-ce-que-la-doctrine-de-...

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg