samedi, 15 décembre 2018

Myth, Satire, and Lucian’s “True History”

Myth, Satire, and Lucian’s “True History”

Ex: http://www.theimaginativeconservative.org

For the ancient myth-maker, there is something at the heart of all of human events that is worth preserving, something marvelous and worthy of renown, even if the account is not entirely true to life…

The second-century satirist, Lucian of Samosata, makes the following inflammatory statement in his True History:

[Historical accounts] are intended to have an attraction independent of any originality of subject, any happiness of general design, any verisimilitude in the piling up of fictions.…I fall back on falsehood — but falsehood of a more consistent variety; for I now make the only true statement you are to expect — that I am a liar. This confession is, I consider, a full defence against all imputations. My subject is, then, what I have neither seen, experienced, nor been told, what neither exists nor could conceivably do so.

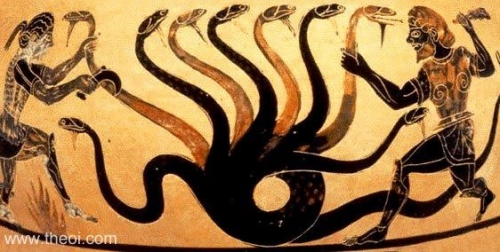

For Lucian, the end of his own peculiar history is to “loosen the mind so that it is in better form for hard study.” While he mentions several “lying” authors by name, and spends a majority of his time in A True History lampooning their accounts; his main argument against these ancient poets, historians, and philosophers is that they “have written many monstrous myths,”[1] following in the tradition of Odysseus, and meant to deceive and overawe the uneducated. Meanwhile, he presents his own narrative as a “new subject, in pleasing style,” with clever references to these same ancient poets, philosophers and historians, “in order that I would not alone lack in the of share myth-making”[2].

Lucian, in response to the poet’s fancy, intends to compose an account in which there is no pretense at truth, and which will surpass the work of the poets because he, at least, has openly declared himself a liar. His goal is to provide a pleasant literary spectacle for the entertainment of his highly educated audience, not unlike the various gladiatorial matches that took place in his own day. But, by describing “myth-making” (mythologeo) in this way, he has misunderstood and therefore, unjustly butchered the goal of the poet, the historian, and the philosopher. For the goal of the ancient myth-maker is not to create an entertaining story or a perfectly accurate description, but to explore and explain aspects of the human experience.

Lucian, in response to the poet’s fancy, intends to compose an account in which there is no pretense at truth, and which will surpass the work of the poets because he, at least, has openly declared himself a liar. His goal is to provide a pleasant literary spectacle for the entertainment of his highly educated audience, not unlike the various gladiatorial matches that took place in his own day. But, by describing “myth-making” (mythologeo) in this way, he has misunderstood and therefore, unjustly butchered the goal of the poet, the historian, and the philosopher. For the goal of the ancient myth-maker is not to create an entertaining story or a perfectly accurate description, but to explore and explain aspects of the human experience.

Myth in the Ancient World

However, before we condemn Lucian too harshly, let us try to understand what he means by “myth.” The troublesome word mythos within its various classical contexts includes definitions ranging from simply “word” (close to the meaning of logos), to the more modern connotation of myth as purely false. Monica Gale, in her work on Myth and Poetry in Lucretius, describes this progression throughout Greek literature: “[Mythos] is frequently employed as a blanket term for anything about which the author is skeptical. Thus Herodotus criticizes the [muthoi] of Homer and the poets only to be reprimanded by Thucydides and Aristotle for his acceptance of [to mythodes] (‘that which resembles mythos’).” Lucian himself follows in this critical tradition, equating the historians’ mythical accounts with those of the ancient rhetoricians, who are concerned with the persuasive power of their accounts, rather than their veracity (puxagogiai). This distinct dilemma, as presented by Lucian and other critics regarding the complete truth or falsity of an account is, according to Gale, misleading at best.

While the term “myth” itself falls into the category of mere falsehood (pseudees) in Lucian’s case, a classical understanding of mythos as its own distinct genre remains. There are two main criticisms that follow the genre as such: that myth is either impious or irrational. These are the basis of Plato’s objection to myth his Republic, saying that it causes confusion within the soul because of its misrepresentation of reality and that it ought not to be recited to any “listeners who do not possess, as an antidote, a knowledge of its real nature,” (Plato X.605c, 595b). However, while Plato and Lucian condemn the myths of Homer, these same myths nevertheless continued to function as the basic source of truth in the education of the Greek world, and even serve to inspire Socrates himself in his allegorical creation of the City in his Republic dialogue.

The Philosopher’s Art of Myth-making

If the purpose of myth-making lies outside of its accuracy, then it must serve some other purpose. We have already seen how Plato condemns the poets in his Republic; however, in excluding the poets from the ideal City, he “put[s] himself to shame and condemn[s] himself when he condemns by word, those who are indeed his fellow-workers and models,” as Carleton L. Brownson argues. Indeed, Strabo, a Roman historian who wrote concerning the study of geography about one hundred years before Lucian, describes the poets themselves as “creative philosopher[s]” (philosophian teen poieetikeen). Strabo goes on to make the distinction between the “fable-making old wife” who invents “whatever she deems suitable for the purposes of entertainment,” and the poet who “’invests’ the hearer with special knowledge.” To illustrate this, he describes Odysseus as a man whose wiliness came not from his skillful rhetoric but from the substance of past experience. In Strabo’s mind, the substance of a poet is not his rhetorical abilities, but the combination of both wisdom and rhetoric; to quote Homer, “’But when he uttered his great voice from his chest, and words like unto snowflakes in winter, then could no mortal man contend with Odysseus.’” Odysseus is so persuasive because he understands a deeper truth that exists in reality and cannot be adequately expressed except in fables.

On the other hand, Lucian views Odysseus as a charlatan,[3] who merely uses his rhetoric to enchant the Phaeacians and gain their favor. His argument is that Odysseus could not have had any experience that would support or add substance to his story and that he was intentionally trying to deceive his audience. Lucian takes this more secular view of myth throughout his works, often referring to it as a pleasing kind of rhetoric, rather than a mode of conveying abstract or abstruse realities. In Lucian’s Lover of Lies, he says that the common people “prefer a lie to the truth simply for its own merits… now what good can they get out of it?” Lucian, again, berates the historians and poets as he did in his introduction to his True History, blaming them for not only deceiving their listeners but using the power of rhetoric to perpetuate ignorance in the people. He offers some defense of the poets, saying that these myths capture the attention of the audience and add luster to the mundane; however, this is the only defense that he gives, and he does not admit any additional substance outside of this rhetorical appeal.

Historians Following in the Poetic Tradition

Herodotus, the historian that Lucian mocks the most in his narrative, begins his own accounts by stating two basic goals: first, “that neither the deeds of men may be forgotten by lapse of time”; and second, that “the works great and marvelous, which have been produced some by Hellenes and some by Barbarians, may [not] lose their renown.” As Lucian and other later historians are so eager to point out, if Herodotus, as a historian, meant to preserve the accuracy of the stories, then he has sadly failed in this respect, because his accounts are either completely fantastic or sadly misinformed. However, that is not what he has told us in the proem. Marc Bloch, in his book on the historical method, describes the element of humanity that is necessary in any historical narrative: “There must be a permanent foundation in human nature and in human society or the very names of man or society become meaningless.” While a perfectly scientific account of any historical event is often considered impossible—even Herodotus admits this in his investigations, quoting the accounts of a variety of sources—he, Herodotus, seems to believe that there is something at the heart of all these human events that is worth preserving, something marvelous and worthy of renown, even if the account is not entirely true to life. Herodotus’ idea of the central meaning of the human existence or the human essence is something that cannot be explained through facts; it is explained in the “great deeds of men.” David Grene elaborates on this point in his introduction to his translation of The Histories: “Herodotus certainly believed in the universal characteristics of the human imagination… He is interested in the eccentricities of men’s beliefs and practices, [for] he is sure of a common core where men think and feel alike.” As Marc Bloch says: “The historian’s job is to make sense of the nearly infinite expanse of historical evidence, just as the poet’s is to make sense of the equally infinite expanse of human experience.”

In that sense, Herodotus, follows the same literary tradition as Homer and Hesiod. The chief difference lies in who controls the actions of history: While Homer and Hesiod focus on the actions of gods, and invoke their aid as they begin their works, Herodotus seeks to understand mankind and his deeds, as we saw in his proem. He, therefore, does not invoke the gods for inspiration but rather calls on his sources for aid in narrating his account, jumping straight from his proem to the varied accounts given by the Persians as to the cause of the Persian war with the Assyrians. Truesdell S. Brown, in his work on The Greek Historians, describes Herodotus’ approach, to history in much the same terms: “Herodotus’ methods cannot be easily reduced to a stylistic formula…[and] he lived well ahead of the formulation of specific rules for prose composition.” The reason why his style is so notoriously hard to track, as many classical critics of Herodotus have observed, is that he is not concerned with the accuracy of his account; indeed, he often casts doubts on his own narrative. His goal is to meditate on and make sense of the “works great and marvelous, which have been produced some by Hellenes and some by Barbarians, [so that they] may [not] lose their renown.” He never makes the pretense at a truly aleethee account, rather, he intends to “publish his findings.”

Modern Defenses of Myth

Within any iteration of truth, the limitations of language, time, and space act as rigorous editors. However, to merely convey accurate factual information is not the same as understanding what it means. The responsibility of the poet, the philosopher, or the historian is to understand and convey a meaning that draws from and explains the significance of the facts. Lucian’s True History serves neither of these ends, for he neither presents anything constructive “[having] nothing true to tell,” nor does he have any experience, “not having any adventures of significance.” In his narrative, he is only critiquing that which is already obvious to his readers, and fostering a kind intellectual pride and chronological snobbery by rejecting the accounts of the ancients. Alexander Pope, a Neo-Classical poet, describes this type of critic in his Essay on Literary Criticism:

The bookful blockhead, ignorantly read,

With loads of learnéd lumber in his head,

With his own tongue still edifies his ears,

and always list’ning to himself appears.

In Pope’s mind, the critic must possess “a knowledge both of books and human kind,” as well as “a soul exempt from pride.” This is in keeping with the classical understanding of education as “encompass[ing] upbringing and cultural training in the widest sense,” with poetry and the poets at the center. The poets in the ancient world not only served as a style guide for other authors but as the foundation for the entire culture, providing an understanding of how to find the answers from the variety of human experience.

C.S. Lewis, another illustrious student in the classical vein, offers a defense of myth along much the same line in his essay “On Stories.” Here Lewis describes the goal of “story” as similar to that of art, by which “we are trying to catch in our net of successive moments something that is not successive…. I think it is sometimes done—or very nearly done—in stories.” Additionally, J.R.R. Tolkien offers his own defense of myth in his essay, “The Monsters and the Critics”: “The significance of a myth is not easily to be pinned on paper by analytical reasoning. It is at its best when it is presented by a poet who feels rather than makes explicit what his theme portends; who presents it incarnate in the world of history and geography, as our poet as done.” This idea is in no way limited to the religious sphere, for both Friedrich Nietzsche in his Birth of Tragedy and Albert Camus in his essay “On Sisyphus” have attested to the inimitable power of myth to express that which is inexplicable about the nature of the universe: “Whatever is profound loves masks,” Nietzsche writes. “Every profound spirit needs a mask.”

Conclusion

By reducing these storytellers to this false dichotomy of pure truth and pure falsehood, Lucian has eviscerated philosophy and history, and left mankind with a meaningless string of facts, dates, abstractions, and reflections. In daring to suppose himself above the gods, he has, intentionally or unintentionally, pitched himself from the height of learning into the void of meaningless abstraction. He does not foster an attitude of learning, but rather a callous existentialism that will cauterize the natural affections of the human heart, rotting the core from the center of a society, and leave the human race, in the end, utterly blind, deaf, and dumb.

Lucian has a full understanding of what he was doing when he uses the terms muthos and mythologeomai to describe the efforts of philosophers, poets, and historians. His concern is for those who have taken the mythos for aleethees (accurate truth), and is speaking up on their behalf. However, this does not justify his dismissal of myth as a genre, nor does his satire constructively contribute to the discussion of meaning in poetry, philosophy, or history. Not only that, but Lucian’s criticism is a sign of a deeper and more troubling problem: that is, the great divorce of the intellectuals from a simple understanding of the world and human nature. Lucian thinks that he has seen through the poets to something greater when, in reality, he has destroyed any hope of finding meaning in the culture that surrounds him.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Notes:

[1 ] “πολλὰ τεράστια καὶ μυθώδη συγγεγραφότωv” (“putting these many lies and myths to paper”)

[2] “ἵνα μὴ μόνος ἄμοιρος ὦ τῆς ἐν τῷ μυθολογεῖν ἐλευθερίας” (“in order that I myself am not left out of this

myth-making”)

[3] “διδάσκαλος τῆς τοιαύτης βωμολοχίας” (“the teacher of these mendicants”)

Works Cited:

Bloch, Marc. The Historian’s Craft. Vintage Book, 1953.

Brown, Truesdell S. Greek Historians. D.C. Heath and Co, 1973.

Gale, Monica. Myth and Poetry in Lucretius. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Grene, David. “Introduction,” History of Herodotus. University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Herodotus. The History of Herodotus, trans. G. C. Macaulay. 1890 edition.

Lewis, C.S. On Stories and other Essays on Literature. ed. Walter Hooper. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, 1983.

Lucian. A True History. Trans. A.M. Harmon. Loeb Classical Library: Harvard University Press, 1913.

Lucian. “A True History”. The Complete Works of Lucian. Vol III. trans. H.W. Fowler and F.G. Fowler. Oxford University Press, 1949.

Lucian. “The Liar (ΦΙΛΟΨΕΥΔΗΣ Η ΑΠΙΣΤΩΝ)”. The Complete Works of Lucian. Vol III. trans. H.W. Fowler and F.G. Fowler. Oxford University Press, 1949.

The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Eds. Hornblower, Simon, and Antony Spawforth.

Nietzsche, Fredrich. Beyond Good and Evil. trans. Walter Kaufmann. Vintage Books. 1989.

Plato. Republic. Plato, Complete Works. ed. Cooper. Hackett, 1997.

Strabo. The Geography of Strabo. trans. Horace Leonard Jones. Loeb Classical Library: Havard University Press, 1913.

Tolkien, J.R.R. “Beowulf: On the Monsters and The Critics.” On The Monsters and The Critics and Other Essays. ed. Christopher Tolkien. Harper Collins, 2007. pp 103-120.

Twain, Mark. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Penguin Classics, 2005.

Renehan, Robert, and Henry George Liddell. Greek Lexicographical Notes: A Critical Supplement to the Greek-English Lexicon of Liddell-Scott-Jones. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht. 1975.

Editor’s Note: The featured image is “Sapho embrassant sa lyre” by Jules Elie Delaunay (1828-1891), courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The image of Lucian is a speculative portrayal taken from a seventeenth-century engraving by William Faithorneis, courtesy of Wikipedia.

00:46 Publié dans Philosophie, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, tradition, mythes, mythologie, antiquité, antiquité classique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les commentaires sont fermés.