Geoffroi de Charny (trans. Elspeth Kennedy), A Knight’s Own Book of Chivalry (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press), 2005.

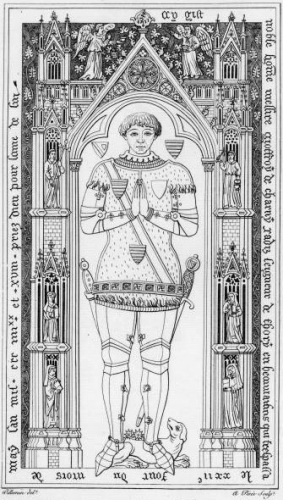

Geoffroi de Charny was a widely respected French lord of the fourteenth century. A bearer of the royal standard (the Oriflamme) and the first recorded owner of the Turin Shroud, he spent his life fighting in various wars before dying fighting the English and Gascons at the battle of Poitiers in 1356, in his late forties.

Geoffroi de Charny was a widely respected French lord of the fourteenth century. A bearer of the royal standard (the Oriflamme) and the first recorded owner of the Turin Shroud, he spent his life fighting in various wars before dying fighting the English and Gascons at the battle of Poitiers in 1356, in his late forties.

Charny was also a writer, producing a number of books, including the Livre de Chevalerie (The Book of Chivalry), one of the few non-fiction descriptions of the knightly ethos that we possess. This book is an exhortation to martial prowess, a spirited defense of the military way life, and a guide to how one should act as a knight.

Charny is unique in combining a downright Homeric competitiveness and spiritedness with a very Christian piety and humility before divine providence. He urges single-minded determination, if necessary unto death:

And no one should give up performing great exploits. For when the body can do no more, the heart and determination should take over; and there are many people who have been more fortunate in the end than they had hoped for at the beginning in relation to the nature of their enterprise. I therefore say: whoever does best is worth most. (10.5-10[1])

One never has an excuse to give up. As in many sections, Charny concludes saying: “qui plus fait, mieux vault” (he who does more is worth more). He says this again and again throughout the work, recurring like a mantra, a kind of final existential statement.

At the same time, Charny is thoroughly imbued with Christian piety. “Ah God!” he often says, thinking gratefully of the natural qualities and opportunity to be a knight granted to him by the Lord. Man has a duty to exploit the natural gifts granted to him by God. One must be humble, for uncertainty is the lot of humanity, our fates determined by an inscrutable divine providence. Hence, Charny urges us to not be arrogant in success, nor despairing in failure, but to be detached and reverent in the face of ever-uncertain events. A lifetime’s work and amassed wealth can be lost in an instant, only the honor of good deeds is eternal.[2] Greed, he says, is the enemy of honor and often leads to self-destruction.

Charny is empowered by his closeness to God:

Now he is indeed a poor wretch who leaves this sweet spring at which everyone can quench his thirst and satisfy all his good desires, for he can only find there a good beginning, a better middle, and a very good end. (44.27)

Interestingly, Charny is not particularly pro-clerical however, seemingly leaping over the priests in his martial piety.

We find again that Homeric wisdom which so often resurfaces in Western literature throughout the ages: that it is better to live well and gloriously, however briefly, than long in servility. The Christian Charny writes:

[A] man is happy to die when he finds life pleasing, for God is gracious toward those who find their life of such quality that death is honorable; for the said men of worth teach you that it is better to die than live basely. (22.50)

He urges the soldier, on a philosophical note, to “live with the constant thought of facing death at any hour on any day” (42.85).

In short, much like the Song of Roland in the eleventh century, Charny’s Book of Chivalry represents a fusion of Christian piety and selflessness with native European spiritedness and martial culture.

The French Hagakure

Charny’s Book of Chivalry can be interestingly compared with Jōchō Yamamoto’s samurai handbook, Hagakure (later studied by Yukio Mishima). The two works are very different in terms of form. Jōchō presents a disordered set of fragmentary memoirs, historical anecdotes, and life advice, collected by an acolyte. Charny by contrast apparently dictated his work in a great burst, as a steady and single-minded torrent of exhortation.

In terms of values, Jōchō and Charny perhaps differ mostly in emphasis. Both are warriors relentlessly convinced of the excellence of their profession, of the need to be the best one can be, and to be unshakably determined unto death. While Charny notes the importance of hierarchy, loyalty and speaking well, Jōchō absolutely stresses the need for selflessness and tact in the service of one’s lord.

The biggest difference is perhaps related to piety. Jōchō, apparently retired as a Zen monk, was basically impious: the samurai’s conscience should not be troubled by what gods or Buddha might want, noting as an afterthought that such selfless service could only be pleasing to deities. Charny by contrast has mind only for war and God.

The Glory of Prowess

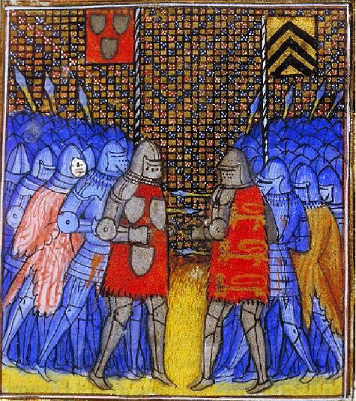

Charny is unwaveringly proud of his profession. For him, martial pursuits are inherently worthwhile, insofar as these entail expensive investments (weapons, armor, steed, travel), risk to oneself (fighting, travel), hardship, determination, and skill. Thus, simple tournaments as well as wars for honor, for one’s inheritance and land, for one’s rightful lord, for self-defense, for helpless orphans and damsels, and for true religion are all impressive and honorable, though not equally so.

Charny recognizes that arms can be misused: robbery, plunder, or stealing from churches bring only “dishonorable ill fame” (41.98). Whereas monastics like Saint Bernard tended to condemn knights in general, praising only the honorable exception of warrior-monks like the knights-templar, Charny inverses the pattern. For him, warriors in general are worthy of praise, whether rich or poor.

Charny’s treatment of wealth and aristocracy is somewhat nuanced. In a striking passage, he argues that, in ancient times, the nobility were chosen because of their powerful physique and capacity to endure, thus earning the right to rule for the benefit of others. Charny asks: “Were they chosen in order to take pleasure in listening to dissolute conversation or in watching worthless pastimes? Indeed no!” (24.108). He notes that the poor have to invest more of their little wealth to go on military adventures, but ultimately considers the rich more honorable, because they have no need to go on such expeditions, but do so purely for “personal honor” (17.80). He urges us however to recognize the merit of each individual whatever his class: “Be sure that you do not despise poor men or those lesser in rank than you, for there are many poor men who are of greater worth than the rich” (23.32).

Natural gifts and humility before God

Charny is among those writers sensitive to the reality of in-born human nature determining differing qualities among individuals. For him, an individual will be blessed by God with different “natural good qualities,” which will make him more or less suited to being a knight. One must build upon these qualities:

[The potentially perfect men-at-arms] is embodied in those who, from their own nature and instinct, as soon as they begin to reach the age of understanding, and with their understanding they like to hear and listen to men of prowess talk of military deeds, and to see men-at-arms with their weapons and armor and enjoy looking at fine mounts and chargers; and as they increase in years, so they increase in prowess and in skill in the art of arms in peace and in war; and as they reach adulthood, the desire in their hearts grows ever greater to ride horses and to bear arms . . . [In time] they double the good to be found them, their own instinct and the will for good which God has given them, they know what is right and spare neither themselves nor what they own in their effort” (16.4-25)

The greatest knight will be simple of heart, pious (and not just outwardly so), intelligent (but not malicious or over-subtle), brave (but not thoughtless), and a good leader or counsel as well as a strong fighter.

Charny presents a selection of ancient heroes, mostly Jewish, to embody his decidedly virile ideal. The ideal warrior will have Samson’s strength, Absalom’s beauty, Solomon’s wisdom, Saint Peter’s piety, and Caesar’s generalship. All of these figures are found wanting however, the only man having all these qualities together being Judas Maccabeus, leader of the Maccabean Revolt against the Hellenistic monarchy. We see here how Judeo-Christian figures became archetypes for a distinctly European martial ideal.

Charny presents a selection of ancient heroes, mostly Jewish, to embody his decidedly virile ideal. The ideal warrior will have Samson’s strength, Absalom’s beauty, Solomon’s wisdom, Saint Peter’s piety, and Caesar’s generalship. All of these figures are found wanting however, the only man having all these qualities together being Judas Maccabeus, leader of the Maccabean Revolt against the Hellenistic monarchy. We see here how Judeo-Christian figures became archetypes for a distinctly European martial ideal.

Charny is certain that the souls of the noble fallen will ascend to Heaven, much as the Vikings believed their fallen would feast forever in Valhalla. The warrior who fights to defend his kinsmen, a maiden’s inheritance, orphans, one’s land or inheritance, or in holy war for true religion can die with “purity of conscience,” unfazed.

Charny’s attitude to priests is somewhat ambiguous, although generally dismissive. He concedes that priests form “the worthiest order of all” (39.1), before adding that knights are “the most rigorous order of all” (40.2). Knighthood “makes greater physical and spiritual demands those those required of any men ordained” (42.60) and there is a greater need for them to be good Christians. Priests should tend to their rituals and mind their own business. Knights however should put on their armor as would priests their robes, armor “which can and should be called the armor of Our Lord” (42.43).

Women should inspire men

In ancient Greece and samurai Japan, a hypermasculine martial culture featured a marked homoerotic strain. By contrast, women have an important place in Charny’s chivalry. Women inspire men to achieve great feats of prowess, are won by such feats, and achieve their own honor through such feats. Charny praises:

the noble ladies who have inspired [men] and through whom they have made their name. And one should indeed honor, serve, and truly love these noble ladies and others whom I hold to be ladies who inspire men to great achievement, and it is thanks to such ladies that men become good knights and men-at-arms” (12.14-17).

A realistic appraisal of sexual competition is then a significant aspect of Charny’s ethos. His concern is not to condemn, but to cultivate romance in such a way that both men and women find their glory.

Importantly, the lovely lady supports a knight because of the social standing she will receive by his successful risk taking, basking in his reflected glory. Charny writes:

Which one of two ladies should have the greater joy in her lover when they are both at a feast in a great company and they are aware of each other’s situation? Is it the one who loves the good knight, and she sees her lover come into the hall where all are at table and she sees him honored, saluted, and celebrated by all manner of people and brought to favorable attention before ladies and damsels, knights and squires, and she observes the great renown and the glory attributed to him by everyone? All of this makes the noble lady rejoice greatly within herself at the fact the she has set her mind and heart on loving and helping to make such a good knight or good man-at-arms. And when she also sees and understands that, in addition to true love for another which they share, he is in addition loved, esteemed and honored by all, this makes her so glad and happy for the great worth to be found in the man who loves her, that she considers her time to have been well spent. (20.1-15)

Women also had a important role in promoting male heroism in ancient Sparta. A cowardly Spartan, if found fleeing a battle, would be shamed or outright killed by his womenfolk. By contrast, women will generally be highly reluctant to support unpopular ‘heretics’ in their risky pursuits, let alone demanding such behavior.

Charny seems to endorse courtly love, that somewhat curious, poetic, and almost anti-social ideal of secret affairs. He urges to “keep secret the love itself and all the benefit and the honorable rewards you derive from it” (19.200) and assures that “the most secret love is the most lasting and the truest” (19.215).[3]

Charny has a fairly practical approach to marriage. Marriage for love in youth is desirable in providing heirs and protecting from sin. Marriage for money is wrong. Marriage in old age, which cannot provide heirs but protects from sin, is acceptable. Charny is disgusted by the latest men’s fashion and excessive wearing of jewelry. He thinks fashion-consciousness is acceptable for women however, as this helps them find a mate and they don’t have other means of showing off, as men do.

The Joy of Struggle

For all his advice, Charny says of the young: “too much good sense is not right for young men at the beginning of their career in arms” (33.5). Young men naturally must take great risks for great rewards and the opportunity to secure their position in society.

Whatever one’s age or station in society, Charny thinks that everyone can contribute through their efforts. The opportunity for glory could present itself at any moment.

[O]ne should not fail in any way to put great efforts into anything which might improve one’s chance of winning an honorable reputation at any moment of the day or night; for the most precious thing there is to lose is time which passes, and cannot be won back nor can it return; and it can happen that such honor is won in an hour which one might fail to find in a year or indeed ever. (19.129-34)

.[Y]ou should know for certain that there is no one who can or should excuse himself from performing well according to his station, some in relation to arms, others in relation to the clerical vocation, others in relation to the affairs of the world. (19.140-5)

.[M]en of standing tell us truly that those who have the will to achieve great worth are already on the way to great achievement . . . they do not care what sufferings they have to endure, but turn everything into great enjoyment. . . . [G]reat good comes from performing these deeds, for the more one does, the less one is proud of oneself, and it always seems there is so much left to do. (19.150-7)

Charny’s Book of Chivalry is a very male and very European celebration of prowess and achievement. This basic competitive and ambitious streak has, no doubt, been responsible for many of Western civilization’s greatest achievements, from the conquests of Antiquity and the explorations of the New World, to the philosophical questioning of the Greeks and the scientific prowess of the Moderns. Qui plus fait, mieux vault!

What follows is Charny’s very practical advice for men-at-arms, much of which will still be relevant for young men today (I have introduced paragraphs).

* * *

There is a supreme rule of conduct required in these good men-at arms as the above-mentioned men of worth inform us: they should be humble among their friends, proud and bold against their foes, tender and merciful toward those who need assistance, cruel avengers against their enemies, pleasant and amiable with all others, for the men of worth tell you that you should not converse at any length nor hold speech with your enemies, for you should bear in mind that they do not speak to you for your own good but to draw out of you what they can use to do you the greatest harm. You should be generous in giving where the gift will be best used and as careful as you can that you let your enemies have nothing that is yours. Love and serve your friends, hate and harm your enemies,[4] relax with your friends, exert yourself with all your strength against your foes.

You should plan your enterprises cautiously and you should carry them out boldly. Therefore the said men of worth tell you that no one should fall into despair from cowardice nor be too confident from great daring, for falling into too great despair can make a man lose his position and his honor, and trusting too much in his daring can make a man lose his life foolishly; but when one is engaged on an armed enterprise, one should dread vile cowardice more than death.

Take care not to be so greedy as to take what belongs to others without good cause. And be sure that, as you value your self, you do not let anything of yours be taken from you. Speak of the achievements of others but not of your own, and do not be envious of others. Above all, avoid quarrels, for a quarrel with one’s equal is dangerous, a quarrel with some one higher in rank is madness, and a quarrel with some one lower in rank is a vile thing, but a quarrel with a fool or a drunk is an even viler thing.

The aforesaid men of worth also tell you to refrain from saying unpleasant things and to make sure that what you say is of some profit rather than merely courteous. And make sure that you do not praise your own conduct nor criticize too much that of others. Do not desire to take away another’s honor, but, above all else, safeguard your own. Be sure that you do not despise poor men or those lesser in rank than you, for there are many poor men who are of greater worth than the rich. Take care not to talk too much, for in talking too much you are sure to say something foolish; for example, the foolish cannot hold their peace, and the wise know how to hold their peace until it is time to speak.

And be careful not to be too guileless, for the man who knows nothing, neither of good nor of evil, is blind and unseeing in his heart, nor can he give himself or others good counsel, for when one blind man tries to lead another, he himself will fall first into the ditch and drag the other in after him. Refrain from remonstrating with fools, for you will be wasting your time, and they will hate you for it; but remonstrate with the wise, who will like you the better for it. Do not put too much faith in people who have risen rapidly above others by good fortune, not merit, for this will not last: they can fall as quickly as they rise. And the aforementioned men of worth tell you that fortune tests your friends, for when it abandons you, it leaves you those who are your friends and takes away those who are not.

I repeat that you should never regret any generosity you may show and any gifts well bestowed, for the above-mentioned men of worth tell you that a man of worth should not remember what he has given except when the recipient brings the gift back to mind for the good return he makes for it. You must avoid acquiring a bad reputation for miserliness in your old age, for the more you have given, the more you should give, for the longer you have lived, the less time you will have yet to live. And above all refrain from enriching yourself at others’ expense, especially from the limited resources of the poor, for unsullied poverty is worth more than corrupt wealth.

The aforementioned men of worth also tell you that you should treat your friends in such a way that you have no need to fear lest they become your enemies, for you should consider that as long as you keep your secret to yourself, it is always within your control, but as soon as you have revealed it, you are at its mercy. And if you have to reveal it, only disclose it to your loyal friend, and disclose your illness only to a loyal doctor.

The aforementioned men of worth also tell you that when moving against your enemies to meet them in battle, never admit the idea that you might be defeated nor think how you might be captured or how you might flee, but be strong in heart, firm, and confident, always expecting victory, not defeat, whether or not you are on top, for whatever the situation, you will always do well because of the good hopes that you have. Indeed, many retreat when, if they had stayed and done what they could, their enemies might have been defeated; and some who have been easily taken prisoner, if they had resisted as well as they could, their enemies would have suffered great losses. You should, therefore, always and in all circumstances be determined to do your best, and above all have the true and certain hope that comes from God that He will help you, not relying just on your strength nor your intelligence nor your power but on God alone, for one often sees that the best men are defeated by lesser men, and a greater number of people may be defeated by a smaller, and the strongest in body may be overcome by the weakest, and the wisest and best ordered in battle by the most foolish and worst ordered.

You can see clearly and understand that you on your own can achieve nothing except what God grants you. And does not God confer great honor when He allows you of His mercy to defeat your enemies without harm to yourself? And if you are defeated, does not God show you great mercy if you are taken prisoner honorably, praised by friends and enemies? And if you are in a state of grace and you die honorably, does not God show you great mercy when He grants you such a glorious end to your life in this world and bears your soul away with Him into eternal bliss? And you can see that no one should be too afraid or too overjoyed or too disturbed at such happenings when they occur, but should give thanks and commit everything into the hands of Him who gives graciously more than one can ask for.

And the aforesaid men of worth teach you that if you want to be strong and of good courage, be sure that you care less about death than about shame. And those who put their lives in danger with the deliberate intention of avoiding shame are strong in all things. The aforesaid men of worth also tell you that you should reflect in your hearts on the things which may happen to you, both the good and the bad, so that you can suffer the bad patiently and treat the good with restraint. And in all adversity be always steadfast and wise.

And you also need to consider how you can and must maintain any benefit or honor which God may bestow on you, so that you do not lose them through negligence such as by removing yourself and distancing yourself from trouble when it comes upon you; and you should first thank and praise Him who gives you these things and preserve them without arrogance, for you must understand that where there is arrogance, there reigns anger and all kinds of folly; and where humility is to be found, there reigns good sense and happiness.

And as the aforesaid men of worth teach you and tell you truly, if arrogance were to be so high that it towered up into the clouds and its highest point reached the heavens, it would have to fall and would crumble and be reduced to nothing. And you should know that from arrogance grow many branches from which many evils come, so many as may cause the loss of soul and body, honor and wealth. You should preserve what you know and the honor you have without arrogance. And what you do not know, you should ask with due humility to be taught it.

The aforesaid men of worth also tell you not to put too much trust in the gifts of fortune, for they are things which are destined to come to an end, whether through loss or illness or force or death, for death spares no one, neither the high nor the low, but levels all. And no one therefore should delay, because such gifts do not last for long, but can vanish at any moment, without waiting for the hour. And the man who perfectly understands this will never be overcome by arrogance. (23.1-117)

Notes

[1] Numbering here refers to section and line in the book.

[2] A striking parallel here with the famous stanza from the Hávamál.

[3] This ideal is very different from Jōchō’s notion of “secret love,” which is also love for men. The idea that the highest love is rendered through helping others, not telling others, and is carried with oneself to the grave.

[4] The Christian Charny has a decidedly pre-Socratic morality here.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.