jeudi, 09 octobre 2014

Corneliu Zelea Codreanu and the Legion of the Archangel Michael

Corneliu Zelea Codreanu and the Legion of the Archangel Michael

by Christophe Dolbeau

The legionary will rather judge man by his soul…

C. Z. Codreanu

A few decades ago, Paris most influential daily, Le Monde, gave some reverberation to a statement from the local antiracist league (LICA) which protested against the coming meeting of « former Romanian fascists » around Archbishop Valerian Trifa who was one of their (alleged) leaders in America. Later on, in 1984, the same Valerian Trifa was back on the front pages as the media gave notice of his deportation from the US to Portugal (he was to die in Estoril in 1987). An American citizen since 1957, the prelate had chosen to forfeit his nationality in 1982 after the notorious Office of Special Investigation had taken proceedings against him, with much encouragement from the pro-communist orthodox patriarchate of Bucharest. In Horizons Rouges (1), general Ion Pacepa, the former head of Romanian intelligence, has since related in detail how the case was made up with fake photographs and manufactured evidence… In 1988, the famous historian and philosopher Mircea Eliade (1907-1986) became in turn an object for sorrowful remarks when his posthumous memoirs made it clear that he had also had « reprehensible sympathies » in his youth… (2).

From these anecdotes, it results that both the clergyman’s and the scholar’s indelible mistake was simply that several decades ago they belonged to the Iron Guard. A great popular movement that overthrew the political scene in Romania, the Iron Guard constituted a peculiar and most controversial phenomenon which keeps a place apart in the history of fascism and still attracts the attention.

« Romanian awake ! » (3)

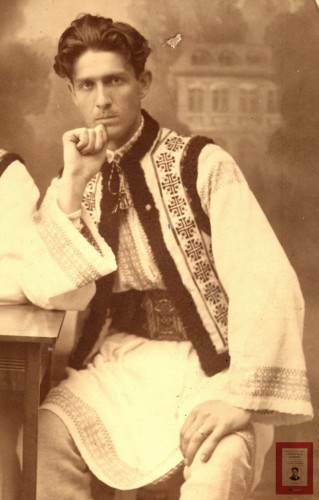

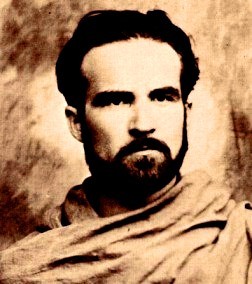

The story began 87 years ago, on Friday June 24, 1927, when together with four friends (Ion Moţa, Ilia Gârneaţă, Corneliu Georgescu and Radu Mironovici), Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, a young doctor of law from Moldavia, laid the foundation of the Legion of the Archangel Michael (Legiunea Arhanghelului Mihail). At that time, Codreanu, aged 28, was already a popular public figure in his country : according to Odette Arnaud (4), « physically he has all the features and traits of the local peasants : he is slim and muscular, sparing of words and gestures, and his bearing is stately. There is no doubt : he commands respect and attention ». Very similar is the description drawn by Jérôme and Jean Tharaud (5) : « In front of me », they write, « a man who is still young ; he is dressed in a rough homespun, his hair are wavy, he has got a high forehead, a blue and cold eyesight, classic features and his gestures are quiet and measured ». To this portrait, Bertrand de Jouvenel (6) adds a few details : « Never did I meet a character », he says, « who introduces himself with so little ostentation and makes such a strong impression. Imagine a very tall and lean man whose face would be a pattern of classical beauty if it were not for deep sockets where a pair of piercing eyes glint ».

Born September 13, 1899, Corneliu Zelea Codreanu attended the Manastirea Dealului military school where he acquired his first patriotic convictions. Galvanized by his father’s red hot patriotism and even though he hadn’t finished school, he did not dither and volunteered to the front during the war (1916). Soon after registering as a law student at Jassy University, he joined the Guard of the National Conscience (1919) ; in May 1922, he founded the Christian Students Association and in March 1923, he joined a fiercely anti-Jewish party called the Christian National Defence League (Liga Aparirii Nationale Crestine)-(7). Eventually, in May 1925, he was prosecuted for the murder of a police commissioner (Constantin Manciu) and triumphantly acquitted (8). His action seemed so justifiable (self-defence)-(9) that 19.300 attorneys had volunteered to plead his cause and the day after he was acquitted, thousands of Romanians cheered at the train which brought the young man back to Jassy. A former French lecturer in this town, Emmanuel Beau de Loménie, throws an interesting light on the case : « Those who speak about the death of the commissioner neglect to say that the man in question was ruling by a system of oriental terror. Whenever he arrested some young anti-Jewish demonstrators, one of his favourite games consisted in hanging them head downwards and whipping their feet with a bullwhip until they fainted » (10).

At that time and for most of his followers, Codreanu was already « a rock among the waves, a road opener, a sword drawn between two worlds » ; he was also the embodiment of new virtues : « thought, fortitude, action, bravery and life » (11).

A religious inspiration

Based on the belief in God, the faith in a mission, mutual love and a fraternal sharing of emotion through choir-singing, the Legion of the Archangel was very different from a political party as we usually conceive it nowadays. « It is not a political movement », says V. P. Garcineanu, « but a spiritual revolution » (12). In Défense de l’Occident (13), Paul Guiraud shares a common sentiment : « This movement », he writes, « has got something unique : it aims at the spiritual and moral recovery of man, at the creation of a new man. This man won’t have anything in common with his democratic predecessor who was both individualistic and weak-minded ». This spiritual reference catches also the attention of Robert Brasillach (14) in Notre Avant-Guerre where he mentions the Legion : « To his legionaries », the young columnist writes, « Corneliu Codreanu directed a rough and variegated poetry ; he appealed to sacrifice, honour, discipline and called for that sort of collective impulse which people usually experience through religion and which he called national ecumenicity » (15). For C. Papanace and W. Hagen (W. Höttl), it was these high moral standards that distinguished the Legion from all other nationalist movements in Europe. According to C. Papanace, « fascism cares about the attire (i.e. the state organization), national-socialism about the body (i.e. racial eugenics) while the Legion attends to the soul (which means its strengthening through the practice of Christian virtues and its preparation with a view to its final salvation) » (16). For W. Hagen, the Legion « had nothing in common with the various copies of fascism and national-socialism that existed in other countries. The difference laid in its Christian religiosity and its mysticism » (17). An intense nationalism combined to a passionate faith made of the Legion an unusual phenomenon which some legionaries saw as the early beginnings of a vast spiritual awakening of the world : « With legionarism », Garcineanu says, « Romanians have created a unique phenomenon in Europe : a movement which possesses a religious structure associated to an ideological corpus that proceeds from Christian theology (…) This is a central fact because in the collective quest for God, it means that all other nations will have to follow us » (18).

Based on the belief in God, the faith in a mission, mutual love and a fraternal sharing of emotion through choir-singing, the Legion of the Archangel was very different from a political party as we usually conceive it nowadays. « It is not a political movement », says V. P. Garcineanu, « but a spiritual revolution » (12). In Défense de l’Occident (13), Paul Guiraud shares a common sentiment : « This movement », he writes, « has got something unique : it aims at the spiritual and moral recovery of man, at the creation of a new man. This man won’t have anything in common with his democratic predecessor who was both individualistic and weak-minded ». This spiritual reference catches also the attention of Robert Brasillach (14) in Notre Avant-Guerre where he mentions the Legion : « To his legionaries », the young columnist writes, « Corneliu Codreanu directed a rough and variegated poetry ; he appealed to sacrifice, honour, discipline and called for that sort of collective impulse which people usually experience through religion and which he called national ecumenicity » (15). For C. Papanace and W. Hagen (W. Höttl), it was these high moral standards that distinguished the Legion from all other nationalist movements in Europe. According to C. Papanace, « fascism cares about the attire (i.e. the state organization), national-socialism about the body (i.e. racial eugenics) while the Legion attends to the soul (which means its strengthening through the practice of Christian virtues and its preparation with a view to its final salvation) » (16). For W. Hagen, the Legion « had nothing in common with the various copies of fascism and national-socialism that existed in other countries. The difference laid in its Christian religiosity and its mysticism » (17). An intense nationalism combined to a passionate faith made of the Legion an unusual phenomenon which some legionaries saw as the early beginnings of a vast spiritual awakening of the world : « With legionarism », Garcineanu says, « Romanians have created a unique phenomenon in Europe : a movement which possesses a religious structure associated to an ideological corpus that proceeds from Christian theology (…) This is a central fact because in the collective quest for God, it means that all other nations will have to follow us » (18).

Anti-Semitism

For the leader of the Legion, Romania’s troubles were primarily due to the Jews. Almost a century later and in view of the wave of anti-Semitic crimes which occured during WWII, this extreme judeophobia seems altogether inadmissible. One should of course replace it in the context of the thirties and remember some enlightening statistics : according to a census of that time, which we borrow from F. Duprat (19), Jews were 10,8% in Bucovina, 7,2% in Bessarabia (and almost 60% of Chisinau’s inhabitants), 6,5% in Moldavia (with a total population of 102.000, Jassy was housing 65.000 Jews) and no less than 140.000 of them lived in the capital-city (which had a total population of 700.000). According to professor Ernst Nolte (20), « between the boyards and the serves, the Jews had formed an intermediate stratum. In some universities and several academic professions and although they did not make up more than 5% of the total population, they outnumbered Romanians. Seventy percent of the journalists and eighty percent of the textile engineers were of Jewish stock. In 1934, almost 50% of the students were non-Romanians (…) Unlike their coreligionists from Austria-Hungary, local Jews did not feel disposed to being assimilated, especially as the prorogation of their former community-status allowed them to secure considerable business advantages ».

In Romania as everywhere else in Europe, Jews aroused the hostility of nationalist circles. It was not exactly a novelty : already in 1866 a bloody riot had broken out in Bucharest when French MP Adolphe Crémieux (21) had offered Romania a loan of 25 million francs in return for the emancipation of Jews. In a stormy atmosphere, members of Parliament had hence been forced to turn down the offer. Considering this past record, the anti-Semitism of the Legion was not so exceptional : after all Iorga’s and Cuza’s National Democratic Party, Marshal Averescu’s People’s Party and Octavian Goga’s National Christian Party (22) had taken the same stand… Besides one should notice that contrary to widely spread clichés, Codreanu never refered to any biological or religious anti-Semitism to justify his anti-Jewish trend. As in the days when Romania was fighting against Turks, Phanariots or Russians, the Legion only confined to an exclusive conception of Romanian national identity. There again one must look back on the crisis of 1866 and remember the words of geographer Ernest Desjardins who wrote : « I can affirm that no religious prejudice ever plaid any part in the government’s decisions nor in the hostility which natives display towards the Jews » (23). Former legionary Faust Bradesco says approximately the same : « Just as it was in the 19th century », he writes, « Legion’s anti-Semitism is nothing but national self-defence (…) Never did the Legion cause any physical harm to the Jews ; it took no notice of race and never damaged any synagogue » (24). Incidentally it appears that Codreanu’s official aims were rather peaceful : wasn’t his major ambition to free Romanians from their inferiority complex and compete with the Jews on their own ground ? An intention he quickly materialized by creating a « legionary trading battalion », cooperative stores, communal canteens, sewing shops, a « legionary market » and a « legionary workers’ corps ».

A noble ideal

To bring national decline to an end and restore the ancient Dacian, the Legion was supposed to be « a school and an army more than a political party » (25). This essential interest for man, as opposed to the corruptible and cosmopolitan politico, was the cornerstone of the movement : « …A new man will rise », Codreanu foretold, « with the qualities of a hero. The Legion will be the cradle of the very best offspring our race can beget : our legionary school will nurture the proudest, noblest, frankest, wisest, purest, bravest and most industrious sons Romania ever had, the noblest souls she ever dreamt up » (26). In this slow process of national revival, woman – mother, daughter, sister or partner – was not forgotten : « In this fight for the better and for the renewal of the Romanian soul », Ion Banea writes (27), « a strong, beautiful and great role is allotted to women (…) We are today in a period of change and struggle. From this battle of honour the woman of our time cannot be absent. We want the woman of our age to be a fighter ; we want her to be a comrade. The times demand it ».

Both in his writings and public speeches, Codreanu harked back again and again to these themes, tirelessly claiming for the restoration of moral requirements which were so stern and austere that F. Bradesco called them « anti-machiavellian » : « All talents », said Codreanu, « brains, education and breeding, are useless to a man who is committed to infamy. Teach your children not to use it either against a friend or even against their worst ennemy (…) In their fight against traitors of all sorts, tell them not to resort to the same disgraceful means. Should they eventually win, they would just exchange roles with their foes. Infamy would stay unchallenged (…) Basically il would carry on ruling the world. Only the light, which flashes out from the hero’s noble and loyal soul, will dispel the shades with which infamy darkened the world » (28).

Stringent ethics

To ponder and practice these principles, legionaries were incorporated into a rather elaborate structure. In addition to the headquarters (the Green House or Casa Verde) it included the « brotherhoods of the Cross » (for children and teenagers), the « citadels » (for women and girls) and above all the « nests » where men could find « a moral milieu propitious to the birth and development of the hero ». In this frame, legionaries could complete their moulding by facing three kinds of ordeals : at first came small personal sacrifices (of time, money and energies), then missions that required heart (to cope with injustice, legal pettifogging and police brutality) and finally situations that necessitated an absolute faith so as to master misgiving, impatience and disillusion. « Only means to contend with human cowardice, hyper-materialism and an unquenchable craving for domination », Faust Bradesco says, « these ordeals allow man to fulfill himself as a person and to grow better as a member of the society » (29). All along that spiritual path, the legionary could be awarded congratulations, mentions, diplomas, ranks (e.g. instructor, vice-commander or commander) and medals (the White Cross for bravery and the Green Cross for deeds of valour). The movement possessed a few special units but globally it was based on a pyramidal organization (with a corresponding hierarchy) : above the « nest », there were the garrison, the district, the department (county) and the region. At the top and next to the Captain, the movement was headed by the Legion Senate (an assembly of wise men, older than 50) and the Council of Commanders (30).

As an echo to the « collective state of mind » and the « national ecumenicity » which Codreanu often refered to and also as a symbol of unity, the Legion wore a uniform (a green shirt). Concurrently the Captain had set forth a series of eight points – moral purity, unselfishness, enthusiasm, faith, the stimulation of the moral forces of the Nation, justice, vitality and New Romania as a final goal – to which every new member personally adhered by taking an oath and solemnly receiving a small bag of Romanian earth. So as to ensure an harmonious development to the movement, this creed was of course associated to the consentaneous principles of order and discipline (31) without which no political action could ever suceed.

Soon the Capitanul (a traditional title of Captain given to great defenders of the Nation) started to lead imposing rides through the country, with hundreds of horsemen wearing white tunics stamped with a Cross. He also opened large working-sites (« The work-camp », Garcineanu writes, « possesses the same beneficial influences upon the Romanian soul as the nest. Only it realizes them in larger proportions. The spiritual effort is deeper, the accomplished results greater, the legionaries in larger numbers. The work-camp, by its scope, is the place and the only modality of anticipating the great legionary life of tmorrow »). Everywhere in Romania, the ascendancy of the Captain grew bigger and bigger (32) : « I have been able to verify », says Odette Arnaud, « that in both Bucharest and Jassy, 80% of the students learn the Cărticica (the breviary of the Legion) by heart (…) I witnessed a pilgrimage of highlanders. They came to kiss the Captain’s hands after walking nearly a hundred leagues, barefoot, with a stick in one hand » (33). Apparently insensible to this new popularity, the leader of the Legion kept cool and collected : according to Beau de Loménie, « he kept perfectly unaffected, good-tempered and genuinely unassuming » (34).

In June 1930, the Legion of the Archangel St Michael became the Iron Guard (Garda de Fier), a name which it was to keep in spite of several bans (June 11, 1931 ; March 1932 ; December 10, 1933). As an emblem it took a square of iron bars (or gard in Romanian language).

The Iron Guard

The Iron Guard

Faithful to the mission assigned to the Legion, Codreanu provided the Iron Guard with a consistent political doctrine which he set out in his book Pentru Legionari (For the Legionaries). He first advocated a ruthless fight against communism which had been successfully implanted by Jewish immigrants from Poland and Russia (between 1914 and 1938, the Jewish population of Romania had grown from 300.000 to 790.000). As a matter of fact, the Captain did not beat around the bush : « When I speak of anti-communist action », he wrote, « I do not mean anti-worker action : when I speak of communists I mean the Jews » (35).

Although King Carol and his suite never ceased making trouble for him, he then stated that he remained a faithful monarchist and rejected any form of republican government. Quite as clearly he condemned democracy as a system which jeopardizes national unity, changes thousands of foreigners into Romanian citizens and proves together erratic, timorous and invariably compliant to great capitalism (36).

Thoroughly scrutinizing the life of the Nation, the chief of the Iron Guard singled out « natural principles of death » and « natural laws of life ». Persuaded that the masses never had any spontaneous intuition of the latter, he suggested that in the future the people should be guided by an elite, that’s to say by « a type of native individuals who possess some special skills ». How will this elite be recruited ? Neither by the ballot-box nor by heredity but by the natural laws of « social selection ». As to the qualities required, the Captain mentioned pureness, working capacity, valour, a strong will to overcome, an ascetic life, faith in God and love. « One should remember », Codreanu said (November 11, 1937), « that the idea of an elite is intrinsically linked to the ideas of sacrifice, poverty and severe life. Whenever the idea of sacrifice is given up, the elite vanishes ».

From a legionary point of view (as expressed by Codreanu himself), the individual is « subordinated to the national community over which the Nation predominates » (37). The Nation includes « all living Romanians as well as the souls of our dead, the graves of our ancestors and all those who will be born Romanian » (38). The Nation owns a physical and a biological patrimony, a material heritage and – as it is also for the Spaniard José Antonio Primo de Rivera (39) – a spiritual legacy which embraces « the way the Nation conceives God, life and the world, as well as the honour and the civilization of the Nation » (40). For the Captain, « the spiritual legacy is the most important » (41). As for the final goal of the Nation, it is the Resurrection (according to the Apocalypse which legionaries often refered to) : « The Nation is a community that will live in the hereafter. Nations are spiritual realities : they not only live here below but also in the reign of God » (42).

The Guard into action

Concurrently to the great strides it organized inside Romania, the Iron Guard began looking forward to an international recognition : in December 1934, Ion Moţa (Codreanu’s brother in law) attended the international fascist meeting of Montreux (Switzlerland), showing thence that the Guard felt more attracted to Rome than Berlin. A couple of years later, when the Spanish War broke out, Codreanu stood up for the nationalists and sent them a symbolic deputation of seven volunteers (Ion Moţa, Father Ion Dumitrescu-Borşa, Prince Alecu Cantacuzeno, Bănică Dobre, Gheorghe Clime, Nicolae Totu and Vasile Marin) led by former general Gheorghe Cantacuzino-Grănicerul. These men left Bucharest on November 26, 1936, they met Francisco Franco and general Moscardo, and joined the Tercio (43). All of them being reserve officers, they were quickly posted (as simple rank and file) to the VIth Bandera and immediately took part in the battle at Las Rozas, Pozuelo and Majadahonda where Ion Mota and Vasile Marin got prematurely killed by an ennemy shell on January 13, 1937 (44).

Within Romania, the conflict with the oligarchy became all the more relentless as the Guard grew more and more representative (from 5 MPs in July 1932, the movement, momentarily renamed Totul Pentru Ţară or Everything for the Country, won up to 60 seats at the elections of December 1937). Persecuted by a regime which went so far as to resort to gangs of thugs and set up a state of emergency in some areas, the Guard will suffer 5.000 deaths between 1927 and 1941. Yet it did not plunge the country into a civil war as it could have done it… It seems therefore particularly undue to picture the Guard as an essentially terrorist organization (which implies that it systematically resorted to violence as a legitimate mean to assume power). Actually when it was involved in violence, it nearly always took the form of limited and targetted actions, conceived as « punishments », whose perpetrators spontaneously surrendered to Justice.

Three of these actions aroused a world wide interest : the execution of Prime Minister Ion Gheorghe Duca by the Nicadorii (at Sinaïa on December 29, 1933), that of Mihai Stelescu by the Decemvirii (on July 16, 1936) and that of Prime Minister Armand Călinescu by the Rasbunatorii (at Cotroceni on September 21, 1939). In the first case, the aim was to punish the man who had quashed the electoral campaign of the Guard and who was responsible for 11.000 arrests, 300 wounded and 6 dead… In the second case, the legionaries wanted to punish a former commander, one of the most brilliant, who had conspired against the Captain’s life, betrayed his oath and become the darling of the Jewish press. Happening at the right moment, this betrayal had had an appalling impact. According to F. Bradesco, « an uneasy feeling was growing among legionaries and a sense of shame was hanging over the Commanders’ Corps » (45). It was therefore decided to strike a spectacular blow (especially cruel, this action proved durably prejudicial. As a matter of fact, Stelescu was killed inside Brancobenesc Hospital where he had just been operated. According to the Tharaud brothers, the murderers shot 38 bullets at him and finished him off with an axe ; writer Virgil Gheorghiu says that they fired 200 bullets and then chopped the body with hatchets !). In the third case, the aim was to avenge the Captain by striking the main promoter of what legionaries usually called Prigoana cea mare or « the Great Persecution ».

As far as terrorism is concerned, one should pay special attention to the case of that Călinescu who prided himself with being the fiercest ennemy of the Iron Guard. Totally subservient to King Carol and the business circles of Bucharest (especially to the king’s mistress Magda Wolf-Lupescu)-(46), he had been displaying a constant hate for the Guard since 1932. Appointed to the governement in December 1937, under foreign pressure and on the eve of new elections, he engaged at once in muzzling the Guard with the most radical means : people were arrested, the police closed some country-roads, meetings were banned, activists placed under forced residence, some of them assaulted, and several areas quarantined. Unfair as they might be, these measures did not prevent the Guard to come third at the poll with 16,09% of the votes. Then, at king’s palace and among power-holders, some disreputable people imagined to get rid of the Guard and its leader for good. Owing to his ferocious zeal, Călinescu was chosen to be the main tool of the plot. At first and after making sure that Patriarch Miron Cristea agreed, the king set up a dictature (February 12, 1938), suspended the Constitution, put off the elections, banned all political parties and declared a state of emergency. Suspecting a snare, Codreanu did not do anything to resist the coup : on his own initiative he dissolved his organization, freed the legionaries from their obligations and advised everyone to keep quiet and patient. When a referendum was called (February 28, 1938) to approve the new Constitution, he deliberately did not ask to vote against it so as not to offer any excuse to further repression. The main result of these tactics was of course to infuriate Călinescu whose provocations redoubled : more legal proceedings poured in, thousands of legionary civil servants were dismissed and all premises and companies of the Iron Guard were arbitrarily closed down. To the minister’s great disappointment this strong pressure proved unavailing as it did not meet the slightest sign of rebellion…

In the end and as the Guard offered no resistance whatever, Călinescu was compelled to find a trivial pretext to engage in the second phase of his anti-legionary operation. On account of a private letter Codreanu had sent to professor Nicolae Iorga, king’s councellor, the latter was encouraged to lodge a complaint for outrage (March 30, 1938) and the Captain was immediately indicted. Arrested on April 17 together with several thousands legionaries (whose possible reaction made the government feel much anxious), Codreanu appeared before a military court (April 19) which sentenced him to a 6 month imprisonment (a maximal punishment for such an alleged offence) ! Incarcerated in Jilava, the leader of the Guard was henceforward at the mercy of his worst enemies. Isolated and seriously ill (from TB), his spirits were low : « Once again my mother is alone », he wrote, « Her son-in-law has died in Spain, leaving a widow and a couple of orphans. I am in jail. Four other children are already in prison or on the verge of being arrested. One of them has also got four children who stay without a crust of bread to eat. Before the holidays, my father went to Bucharest to draw his pension and he never returned. He was arrested, led to an unknown place and no one knows about his fate » (47).

At this stage, it seemed that the government had reached its objective : the Iron Guard was paralyzed, its most active supporters were disqualified and its leader in gaol. Still Călinescu wanted to complete his work. With this aim in view, he initiated new proceedings (May 8, 1938) against Codreanu in order to have him sentenced for treason and armed rebellion. Appearing before Bucharest military court (May 23) after a quick investigation and whereas his lawyers had only had three days to prepare the plea, the Captain miraculously escaped the death penalty (just established on May 24…) but he however got ten years of hard labour (May 27, 1938) !

The denial of justice was enormous, the masquerade patent, yet Călinescu’s employers were not satisfied. Neither the king nor his hidden abettors felt reassured as they perfectly knew that many legionary groups were still secretly at work (in 1937 there were 34.000 « nests »), that some commanders had escaped police raids and that their chief was still alive. Once more the Home Secretary set to work, more than ever determined to do in the Captain and his men. Throughout summer, the police went on arresting people so as to weaken the Guard a little more ; precautions were even taken in the army to prevent any outburst of temper from sympathizers. Eventually, in November, everything was ready and Călinescu gave the green light. In the night from November 29 to November 30, 1938, Codreanu and 13 other legionaries (the Nicadorii and the Decemvirii) were taken out from Râmnicu-Sarat jail and handed over to major Dinulescu and a company of gendarmes. The police vans took the road to Bucharest, they stopped on the edge of Tâncăbeşti Forest and there, the 14 prisoners were coldly strangled by their custodians who also riddled them with bullets to simulate an escape bid. Afterwards, the corpses were brought to Jilava, sprayed with sulfuric acid and burried in several tons of concrete (48) ; then, general Ioan Bengliu gave each killer a bonus of 20.000 lei.

Călinescu had but a short while to jubilize. As expected he was not long to pay for his crime with his life (49) : on September 21, 1939, a group of avengers shot him dead in Cotroceni. As for the tragic death of Codreanu, at the age of 39, it highlights the message which the Captain used to address to his young supporters : « Fight but never be vile. Leave to others the ways of infamy. Better fall with honour than win uncreditably » (50).

War, Resistance and Exile

The punishment inflicted to Călinescu (51) led to a stinging counterstroke : the executioners were immediately shot on the spot without any trial. Whereupon general Argeşanu gave the order to kill all legionary officers who happened to be incarcerated at the moment as well as five ordinary legionaries in each county (that is to say between 300 to 400 dead in 24 hours !)-(52). In spite of these repeated blows, the Iron Guard survived ; under the leadership of a new chief, Horia Sima (1907-1993), it even entered the governement in September 1940 (Horia Sima, Prince Sturdza, prof. Brăileanu, legionaries Nicolau and Iasinschi were appointed ministers). Thenceforth the settling of accounts began : on November 27, 1940, former minister Victor Iamandi, generals Gheorghe Argeşanu, Ioan Bengliu and Gabriel Marinescu were summarily executed in Jilava together with senior police officers Moruzov and Stefanescu (53) ; on the same day Nicolae Iorga, the man who had told the king to get rid of Codreanu, was assassinated in Strejnicu (54). On the other hand and contrary to the usual stereotypes, the legionary movement did not start any pogrom. According to the Black Book (Cartea Neagra) which Matatias Carp published in 1946 with a foreword by Chief Rabbi Alexandru Safran, « during the legionary government (from September 6, 1940, to January 24, 1941) casualties were as follows : 4 Jews killed in Bucharest in November ; 11 Jews killed in Ploeşti in the night of November 27 ; 1 Jew killed in Hârşova (Constanta) on January 17, 1941, and 120 Jews killed between January 21 and January 24, 1941, during the rebellion » (volume 1, p. 25). No doubt this balance of 136 victims is terrible (55) but as a comparison one should remember that up to 265.000 Jews died under Marshal Antonescu’s anti-legionary regime… [Is it necessary to add that the Legion took absolutely no part in the alleged pogroms of Jassy (June 27, 1941), Edinets (July 6, 1941), Cernăuţi (July 9, 1941), Chisinau (August 1, 1941) and Odessa (October 1941-January 1942) ? As explained below, the movement was dissolved and prohibited in January 1941. The pogroms if they ever happened were the sole responsability of Antonescu and his acolytes].

The Iron Guard did not stay at the head of the state for long. On January 21, 1941 and by means of a large police operation backed by German Wehrmacht (general E. O. Hansen), Marshal Ion Antonescu tried to extirpate the legionaries for good (at least 800 of them were killed and 8000 arrested). Under German protection, the surviving commanders had no alternative but to flee to Germany where Himmler had them confined in Buchenwald, Dachau, Berkenbruck and Sachsenhausen (56). According to Walter Hagen (57), « the crushing of the legionary movement deprived the regime of any popular support. It became a “dead system“, very similar to the dictatorial government of Carol II. When danger came, nobody lifted a finger to defend it ». Arrested (August 23, 1944) and handed over to the Soviets by order of King Michael and Iuliu Maniu, the Conducător (Antonescu) ended his life facing a communist firing squad.

Released on August 24, 1944, the day after Romania’s volte-face, the legionaries from Germany set up (December 10, 1944) a « Romanian National Government » (with Horia Sima, Prince Sturdza, general Chirnoagă) which settled in Vienna and later in Bad Gastein and Altaussee. They also formed a small anti-communist army which went to fight along river Oder. This Romanian unit was made of two Waffen-SS regiments (5.000 men) whose commanding officer was general Platon Chirnoagă (1894-1974). « In the circumstances », Horia Sima says (58), « the Iron Guard had no choice but to carry on the fight (…) Therefore I issued a proclamation to the country which was immediately broadcast. Then I began organizing the resistance with the scanty means we still had at our disposal ».

As in most East European countries, the resistance began with a very poor equipment, in a territory which the Red Army had just ravaged and where all sorts of communist gangs were wreaking havoc (from March 6, 1945, these thugs became the senior executives of the new political police)-(59). At that time no support was to be expected from either the king or his friends (540.000 Romanian soldiers were now fighting against Germany together with the Soviets). Though he had just been awarded the Order of the Victory, King Michael (born 1921) was no more than a mere hostage in the hands of Vichinsky, P. Groza, Gheorghiu-Dej, V. Luca, Ana Pauker or Emil Bodnăraş, and he had no choice but to drain the cup to its dregs. On December 30, 1947 he nevertheless resolved to abdicate and leave the country. In spite of draconian measures of repression (arrests, mass deportations, shootings), guerillas sprang up in Oltenia, Banat, Transylvania and along the Carpathian Mountains ; led by former legionaries, these groups went on fighting until 1955-1956 almost without any help from abroad (60). Beyond their own ideas, this hard-line attitude was a question of life and death for the former members of the Iron Guard. Actually under a new law passed in May 1948, they were irrevocably destined for the hardest punishments, which meant that they would end up in some infamous death camps (such as Black Sea Canal, Cavnic, Peninsula, Aiud) and suffer the « unmaskings » or brainwashings to which all intellectuals were submitted at Piteşti, Gherla and Jilava special prisons (61).

For the expatriates the fight went on as well (62) but in a less hostile environment. Well established in the Romanian emigration (in Germany, France, Spain, Brazil and the USA) they launched several publications, did their best to inform the Western public (63) and took an active part in various assemblies of captive nations. According to the declaration they issued in 1977 (50th aniversary of the Legion) their positions ensued from their former commitments. The Iron Guard in exile demanded that international communism should be eradicated, it rejected the UNO and the Helsinki Agreement, proposed to build a united Europe with a common spiritual denominator and to support East European resistance movements ; it also rejected any idea of « world government » and flatly repelled the concept of « spheres of influence ». Vis-à-vis the inner situation of Romania, it denied Ceauşescu any legitimacy, reaffirmed Romanian rights on Bucovina, Bessarabia and the Hertza region (annexed by the USSR), rejected collectivism and demanded religious freedom.

For the expatriates the fight went on as well (62) but in a less hostile environment. Well established in the Romanian emigration (in Germany, France, Spain, Brazil and the USA) they launched several publications, did their best to inform the Western public (63) and took an active part in various assemblies of captive nations. According to the declaration they issued in 1977 (50th aniversary of the Legion) their positions ensued from their former commitments. The Iron Guard in exile demanded that international communism should be eradicated, it rejected the UNO and the Helsinki Agreement, proposed to build a united Europe with a common spiritual denominator and to support East European resistance movements ; it also rejected any idea of « world government » and flatly repelled the concept of « spheres of influence ». Vis-à-vis the inner situation of Romania, it denied Ceauşescu any legitimacy, reaffirmed Romanian rights on Bucovina, Bessarabia and the Hertza region (annexed by the USSR), rejected collectivism and demanded religious freedom.

As Corneliu Zelea Codreanu had predicted : « Legionaries do not die. Standing upright, steadfast and immortal, they victoriously gaze at the seething of ineffectual hates » (64). In 1989, after 45 years of communist rule, the survivors of the Guard had not changed : they were still faithful to their oath and sticked to their creed (social fraternity, distributive justice, inner perfection and creative revolution). After the fall of Ceauşescu, those who lived in Romania (mostly octogenarians) kept cautious and contented themselves with supporting the traditional right-wing parties. For them, the country was not yet fully safe : the late dictator’s henchmen were still powerful and the new democracy unsteady. Wasn’t it amazing to see the Romanians, totally messed up, cheer up King Michael (in February 1997), the very man who had abandoned them to Stalin and given up a good third of the country ? Writing about the ethnic quarrels which broke out in Transylvania, some journalists suggested that a new Iron Guard stood behind the nationalist movement Vatra Românească and the Association for a United Romania (65). Probably meant for the omnipotent western antifascist lobby, the allegation was immediately taken up by Petre Roman (March 21, 1990) ; it came at the right moment for a most controversial regime whose repressive policy it greatly contributed to justify. Obviously this was grossly overstated and at any rate much premature. Today, Romania is very different from what it used to be in the thirties or the fourties (66) and the Iron Guard is not a simple political party which disappears and reappears according to circumstances. It has a metaphysical dimension which cannot be so easily restored in a country that has been submitted for nearly 50 years to atheism, materialism and utilitarianism. If the legionary movement is ever to revive, it will be under the spur of a new elite (as Codreanu meant it)-(67) and it will need years to develop !

Christophe Dolbeau

Notes

(1) Horizons Rouges, Paris, Presses de la Cité, 1988, pp. 217-221.

(2) For the same reason, criticisms were also directed at philosopher and poet Émile Cioran (1911-1995). In a letter dated March 4, 1975, the Romanian-French academician Eugène Ionesco (1909-1994) writes : « Towards the end of the inter-war years, most Romanians, especially young people and intellectuals, were members or sympathizers of the Romanian fascist party called the Iron Guard » – quoted by J. Miloe in La Riposte, Paris, Compagnie Française d’Impression, 1976, p. 309.

(3) Title of a famous poem by the Transylvanian Andreiu Muresianu (1816-1863).

(4) La Revue Hebdomadaire, March 2, 1935.

(5) L’Envoyé de l’Archange, Paris, Plon, 1939, p. 2. Both Jérôme (1874-1953) and Jean (1877-1952) Tharaud were novelists who belonged to the French Academy.

(6) The son of a Jewish mother, Bertrand de Jouvenel (1903-1987) was a famous fascist journalist who later became a much respected economist.

(7) The banner of the League was black and there was a white circle with a swastika in the middle. The League was presided over by professor Alexandru C. Cuza (1857-1947).

(8) According to Codreanu, « All the gentlemen of the jury wore a tricolour cockade with a swastika » – in La Garde de Fer, Grenoble, Omul Nou, 1972, p. 231. See https://archive.org/details/ForMyLegionariesTheIronGuard

(9) On October 25, 1924 C. Z. Codreanu was defending a young student at the tribunal of Jassy. All of a sudden and during the hearing, commissioner Manciu and a dozen policemen burst into the court room and rushed to Codreanu who seized his gun and fired to protect himself – See La Garde de Fer, p. 210.

(10) La Revue Hebdomadaire, December 17, 1938, vol. XII, p. 346.

(11) Ion Banea, Lines for our Generation, Madrid, Libertatea, 1987, p. 13-14.

(12) V. Puiu Gârcineanu, From the Legionary World, Madrid, Libertatea, 1987, p. 1.

(13) N° 81 (April-May 1969), p. 9-10.

(14) Born in 1909 in the South of France, Robert Brasillach was a promising poet but also a bestselling novelist and a brilliant journalist ; sentenced to death in January 1945 for « collaboration with the nazis », he was executed on February 6, 1945.

(15) Notre Avant-Guerre, Paris, Plon, 1973, p. 304.

(16) Introduction to the Livret du Chef de Nid (Handbook of the Nest Leader), Pământul Strămoşesc, 1978, s.l., p. VI.

(17) Le Front Secret, Paris, Les Iles d’Or, 1952, p. 234.

(18) V. Puiu Gârcineanu, op. cit., p. 14. The Christian inspiration of the movement attracted a great number of clergymen ; approximately 3.000 priests (out of 10.000) belonged to the Legion. In 1945, out of 12 bishops in the Synod, 7 were former legionaries.

(19) Revue d’Histoire du Fascisme, N° 2 (September-October 1972), p. 132.

(20) Les Mouvements Fascistes, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1991, p. 237.

(21) Adolphe Crémieux (1796-1880) was a Jew and a freemason ; from 1863 to 1880, he was the president of the Alliance Israélite Universelle (World Jewish Alliance).

(22) The symbol of the National Christian Party was the swastika.

(23) See Les Juifs de Moldavie, Paris, Dentu, 1867.

(24) Les Trois Épreuves Légionnaires, Prométhée, 1973, s. l., p. 69. This opinion is shared by Prince Mihail Sturdza who states that Codreanu « would have immediately expelled from the Movement any fool who had so much as broken a window in a Jewish-owned shop » (The Suicide of Europe, p. 233) and by Father Vasile Boldeanu who assures that « there was no room for anti-Semitism in the legionary programme » (quoted in La Riposte, p. 194).These opinions are perhaps a bit too « optimistic » and in any case they seem to be contradicted by the long series of outrages which the Jewish community suffered at that time (taking into consideration that all the attacks were not always due to legionaries and that they often occured as retaliatons to previous assaults by Jewish thugs as in Oradea, December 1927).

(25) La Garde de Fer, p. 283.

(26) Ibid, p. 283.

(27) Ion Banea, op. cit., p. 10-11.

(28) La Garde de Fer, p. 277.

(29) Les Trois Épreuves Légionnaires, p. 158.

(30) See F. Bradesco, Le Nid – Unité de Base du Mouvement Légionnaire, Madrid, Carpatii, 1973.

(31) See C. Z. Codreanu, Le Livret du Chef de Nid, Pamântul Stramosesc, 1978, and F. Bradesco, Le Nid, pp. 111-135.

(32) The Legion-Iron Guard had grown from an obscure little group into a large movement whose membership included generals (Gheorghe Cantacuzeno, Ion Macridescu, Ion Tarnoschi), scholars (Traian Brăileanu, Ion Găvănescul, Eugen Chirnoagă, Corneliu Şumuleanu, Dragoş Protopopescu), distinguished philosophers (Nichifor Crainic, Nae Ionescu) and brilliant poets (Radu Gyr, Virgil Carianopol). The masses were also enthusiastic : when Codreanu got married (June 13, 1925), a crowd of 80.000 to 100.000 flooded to Focşani and at the funerals of Moţa and Marin (February 13, 1937), the cortège (with a hundred priests) stretched out over 6 miles. In 1937 and according to S. G. Payne, the Iron Guard had a membership of 272.000 (i.e. 1,5% of the Romanian population).

(33) La Revue Hebdomadaire, March 2, 1935.

(34) La Revue Hebdomadaire, December 17, 1938, p. 348.

(35) La Garde de Fer, p. 353. Before WWII there were approximately 300.000 factory workers in Romania and the local Communist Party had no more than 1000 members. Indubitably most communist leaders – Dr Litman Ghelerter, Ilie Moscovici, Marcel and Ana Pauker (Hannah Rabinsohn), Avram Bunaciu (Abraham Gutman), Walter Roman (Ernö Neuländer), Teohari Georgescu (Burah Techkovich), Gheorghe Apostol (Aaron Gerschwin), Miron Constantinescu (Mehr Kohn), Leonte Răutu (Lev Oigenstein), Remus Kofler, Simion Bughici (David), Iosif Chişinevschi (Iacob Roitman), Gheorghe Stoica (Moscu Cohn), Stefan Voicu (Aurel Rotenberg), etc – were Jews.

See : http://en.metapedia.org/wiki/List_of_communist_Jews_in_Romania

(36) Ibid, pp. 386-388.

(37) Ibid, p. 396.

(38) Ibid, p. 398.

(39) See Horia Sima, Dos Movimientos Nacionales, José antonio Primo de Rivera y Corneliu Codreanu, Madrid, Ediciones Europa, 1960.

(40) La Garde de Fer, p. 398.

(41) Ibid, p. 398.

(42) Ibid, p. 399.

(43) The Tercio is the Spanish Foreign Legion.

(44) José Luis de Mesa, Los otros internacionales, Madrid, Barbarroja, 1998, pp. 165-172, and Los legionarios rumanos Motza y marin caidos por Dios y España, Barcelona, Bausp, 1978. The mortal remnants of the two legionaries were repatriated by train and the funerals took place in Bucharest on February 13, 1937. Legionaries Clime, Cantacuzeno, Dobre and Totu came back safe and sound but they were assassinated by the Romanian secret police in September 1939 ; Father Dumitrescu (1899-1981) received a 16-year sentence in 1948.

(45) F. Bradesco, La Garde de Fer et le Terrorisme, Madrid, Carpatii, 1979, p. 97.

(46) Born in a Jewish family from Jassy, Helen Wolf (1895-1977) became the king’s mistress in 1925 ; she later married Carol II (the marriage took place in 1947 in Rio de Janeiro) and from then onwards she was called Helen of Hohenzollern…

(47) C. Z. Codreanu, Journal de Prison (Prison Diary), Puiseaux, Pardès, 1986, p. 18-19.

(48) On December 6, 1940, they were transfered to the Green House in the presence of 120.000 legionaries.

(49) Unanimously decided by the Legionary High Command in Berlin, the operation was carried out by a group of nine volunteers led by young attorney Miti Dumitrescu.

(50) C. Z. Codreanu, Le Livret du Chef de Nid, p. 7 (Basic rule N° 6 of the « nest »).

(51) In a circular-letter (N° 145) dated February 11, 1928, C. Z. Codreanu had explicitly asked his friends to avenge him in case of a murder – See F. Bradesco, La Garde de Fer et le Terrorisme, p. 190.

(52) The sinister balance of these reprisals is far from acurate : according to V. Gheorghiu, 242 legionaries were killed whereas Father Boldeanu speaks of 1300 victims. Be it as it may, in absence of legal proceedings this massacre was mere state-terrorism.

(53) In a letter dated April 5, 1936, C. Z. Codreanu gave his legionaries the following advice : « Don’t confuse justice and Christian forgiveness with the right and the duty of a people to punish those who betrayed and those who dared opposing the Nation’s destiny. Don’t forget that you have girded on the sword of the Nation. You carry it in the name of the Nation. And in the name of the Nation you shall punish, mercilessly and without any pardon » – La Garde de Fer, p. 443.

(54) The authors of this merciless retribution were executed in their turn on December 4, 1940 and July 28, 1941.

(55) Once more the balance is uncertain : regarding the events of January 1941, F. Bertin speaks of 400 victims, F. Duprat of 680 and Father Boldeanu goes up to 1352 (122 Jews, 430 legionaries and 800 undetermined). For their part, some representatives of the Jewish community (different from M. Carp and Rabbi Safran) put forward a total of 5.000 to 6.000.

(56) Treated as Ehrenhäftlinge or honorary prisoners, many legionaries were apparently not interned with the other inmates but granted better conditions. At Buchenwald for instance several of them stayed in Fichtenheim barracks which housed the camp garrison.

(57) W. Hagen, op. cit. , p. 244.

(58) Interview by G. Gondinet in Totalité N° 18-19 (summer 1984), p. 20.

(59) See Reuben H. Markham, La Roumanie sous le joug soviétique (Rumania under the Soviet yoke), Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1949.

(60) However a few parachute landings were organized by political emigrants and foreign secret services : for instance 13 young paratroopers of the Resistance (Ion Buda, Aurel Corlan, Ion Cosma, Gheorghe Dincă, Ion Golea, Ion Iuhasz, Gavrilă Pop, Mircea Popovici, Ion Samoilă, Alexandru Tănase, Erich Tartler, Ion Tolan and Mihai Vasile Vlad) were sentenced to death and executed in October 1953. All former legionaries did not choose to resist and a minority prefered to adapt and collaborate : such was the case of Father Constantin Burducea who became minister of religious affairs (from March 6, 1945 to April 1946) and Nicolae Petrescu (the last general-secretary of the Iron Guard) who reappeared on the political scene between 1945 and 1948.

(61) See D. Bacu, The Anti-Humans, Englewood, Soldiers of the Cross, 1971 and G. Dumitresco, L’Holocauste des Âmes, Paris, Librairie Roumaine Antitotalitaire, 1998.

(62) In 1947, the Instructing Commission of the International Tribunal of Nuremberg exculpated the Legion, the Romanian National Government and the Romanian National Army ; yet the Iron Guard decided to dissolve in 1948.

(63) Sometimes more spectacular actions were organized as in Bern where, between February 14 and February 16, 1955, the Romanian embassy was raided by political emigrants Stan Codrescu, Dumitru Ochiu, Ion Chirilă and Puiu Beldeanu who killed colonel Aurel Setu, head of the Romanian secret service in Switzlerland.

(64) La Garde de Fer, p. 4.

(65) See for instance the scholar magazine Hérodote, N° 58-59, p. 300.

(66) Today Romania belongs to the EEC, it is a much secular country where communism is only a bad memory and where the Jewish community is reduced to barely 20.000 persons (for a global population of 21,5 million).

(67) In 1996 a small group of neo-legionaries from Timisoara began to publish a magazine called Gazeta de Vest. On January 15, 2000 the French daily Le Monde reported that on November 8, 1999 a religious service had been celebrated in Jassy, in memory of the Moldavian dead legionaries ; according to the Paris newspaper this service marked the official rebirth of the Legion. In 2014, the Noua Dreaptă (New Right) claims that it carries on the legacy of the Legion ; it is not a political party but a philosophical movement which does not stand for elections (see http://nouadreapta.org).

Bibliography

– BACU D., The Anti-Humans, Englewood, Soldiers of the Cross, 1971.

– BANEA I., Lines for our Generation, Madrid, Libertatea, 1987.

– BERTIN F., L’Europe de Hitler, volume 3, Paris, Librairie Française, 1977.

– BRADESCO F., Antimachiavélisme Légionnaire, Rio de Janeiro, Dacia, 1963 ; Le Nid, unité de base du Mouvement Légionnaire, Madrid, Carpatii, 1973 ; Les Trois Épreuves Légionnaires, Paris, Prométhée, 1973 ; La Garde de Fer et le Terrorisme, Madrid, Carpatii, 1979.

– CABALLERO C. and LANDWEHR R., El Ejército Nacional Rumano. Romanian Volunteers of the Waffen SS 1944-45, Granada, García Hispán, 1997.

– CODREANU C. Z., Le Livret du Chef de Nid, Pamântul Stramosesc, 1978, s. l. ; La Garde de Fer, Grenoble, Omul Nou, 1972 ; Journal de Prison, Puiseaux, Pardès, 1986.

– DE MESA J. L., Los otros internacionales, Madrid, Barbarroja, 1998.

– DESJARDINS E., Les Juifs de Moldavie, Paris, Dentu, 1867.

– DUMITRESCO G., L’Holocauste des Âmes, Paris, Librairie Roumaine Antitotalitaire, 1998.

– GARCINEANU V. P., From the Legionary World, Madrid, Libertatea, 1987.

– GOLEA T., Romania beyond the limits of endurance, Miami Beach, Romanian Historical Studies, 1988.

– GUERIN A., Les Commandos de la Guerre Froide, Paris, Julliard, 1969.

– HAGEN W., Le Front Secret, Paris, Les Iles d’Or, 1952.

– MARCKHAM R. H., La Roumanie sous le joug soviétique, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1949.

– MILOE J., La Riposte, Paris, Compagnie Française d’Impression, 1976.

– NOLTE E., Les Mouvements Fascistes, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1991.

– PACEPA I., Horizons Rouges, Paris, Presses de la Cité, 1988.

– SBURLATI C., Codreanu e la Guardia di Ferro, Roma, Volpe, 1977.

– SIMA H., Destinées du Nationalisme, Paris, Prométhée, 1951 ; Dos Movimientos Nacionales, José Antonio Primo de Rivera y Corneliu Codreanu, Madrid, Ediciones Europa, 1960 ; Histoire du Mouvement Légionnaire, Rio de Janeiro, Dacia, 1972.

– SIMA H. (D. CRETU and F. BRADESCO), Le Semi-Centenaire du Mouvement Légionnaire, Madrid, 1977.

– STURDZA M., The Suicide of Europe, Boston-Los Angeles, Western Islands Publishers, 1968.

– THARAUD J. and J., L’Envoyé de l’Archange, Paris, Plon, 1939.

– XXX, Los legionarios rumanos Motza y Marin caídos por Dios y por España, Barcelona, Bausp, 1978.

– La Revue Hebdomadaire, March 2, 1935 and December 17, 1938.

– Nuova Antologia, February 1, 1938 (« Codreanu e il Legionarismo Romeno »)

– Défense de l’Occident, N° 81 (April-May 1969)

– Revue d’Histoire du Fascisme, N° 2 (September-October 1972).

– Totalité, N° 18-19 (Summer 1984).

– Le Choc du Mois, N° 28 (March 1990).

– Hérodote, N° 58-59 (1990).

– Quaderni di Testi Evoliani, N° 29.

French speaking readers will find a very complete set of texts about the ideology of the Iron Guard at http://vouloir.hautetfort.com/archive/2010/05/19/codreanu.html

00:05 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, codreanu, roumanie, années 30, mouvement légionnaire, légion archange michel, archange michel |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 15 mars 2013

Codreanu sur Méridien Zéro

EMISSION N° 136

"CORNELIU ZELEA CODREANU ET LA GARDE DE FER"

18:25 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : méridien zéro, codreanu, roumanie, histoire, europe danubienne, garde de fer, légion archange michel |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 11 septembre 2011

Mircea Eliade: Liberty

Liberty

By Mircea Eliade

"Iconar", March 5, 1937 There is an aspect of the Legionary Movement that has not been sufficiently explored: the individual’s liberty. Being primarily a spiritual movement concerned with the creation of a New Man and the salvation of our people – the Legion can’t grow and couldn’t have matured without treasuring the individual’s liberty; the liberty that so many books were written about with which so many libraries were stacked full, in defense of which many

There is an aspect of the Legionary Movement that has not been sufficiently explored: the individual’s liberty. Being primarily a spiritual movement concerned with the creation of a New Man and the salvation of our people – the Legion can’t grow and couldn’t have matured without treasuring the individual’s liberty; the liberty that so many books were written about with which so many libraries were stacked full, in defense of which many

democratic speeches have been held, without it being truly lived and treasured.

The people that speak of liberty and declare themselves willing to die for it are those who believe in materialist dogmas, in fatalities: social classes, class war, the primacy of the economy, etc. It is strange, to say the least, to hear a person who doesn’t believe in God stand up for “liberty,” who doesn’t believe in the primacy of the spirit or the afterlife.

Such a person, when they speak in good faith, mix “liberty” up with libertarianism and anarchy. Liberty can only be spoken of in spiritual life. Those who deny the spirit its primacy automatically fall to mechanical determinism (Marxism) and irresponsibility.

There are, however, spiritual movements wherein people are tied by liberty. People are free to join this spiritual family. No exterior determination forces them to become brothers. Back in the day when it was expanding and converting, Christianity was a spiritual movement that people joined out of the common desire to spiritualize their lives and overcome death. No one forced a pagan to become a Christian. On the contrary, the state on the one hand, and its instincts of conservation on the other, restlessly raised obstacles to Christian conversion.

But even faced with such obstacles, the thirst of being free, of forging your own destiny, of defeating biological and economic determinations was much too strong. People joined Christianity, knowing that they would become poor overnight, that they would leave their still pagan families behind, that they could be imprisoned for life, or even face the cruelest death—the death of a martyr.

Being a profoundly Christian movement, justifying its doctrine on the spiritual level above all – legionarism encourages and is built upon liberty. You adhere to legionarism because you are free, because you decided to overcome the iron circles of biological determinism (fear of death, suffering, etc.) and economic determinism (fear of becoming homeless). The first gesture a legionnaire will display is one born out of total liberty: he dares to free himself of spiritual, biological and economic enslavement. No exterior determinism can influence him. The moment he decides to be free is the moment all fears and inferiority complexes instantaneously disappear. He who enters the Legion forever dons the shirt of death. That means that the legionnaire feels so free that death itself no longer frightens him. If the Legionnaire nurtures the spirit of sacrifice with such passion, and if he has proven to be capable of making sacrifices – culminating in the deaths of Mota and Marin – these bear witness to the unlimited liberty a legionnaire has gained.

http://www.archive.org/details/Liberty_7

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : roumanie, légion archange michel, codreanu, mircea eliade, histoire, années 30 |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook