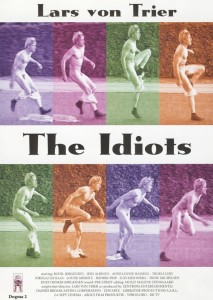

The Idiots (Idioterne) is not an accessible film, and neither is it is easy to digest. The sexual content is so extreme that The Idiots is rated the same as any pornographic film in the United Kingdom, Spain, Australia, Norway, and several others. The depiction of mentally disabled individuals, both real and those merely acting as such, is alarming and controversial. During the screening at the Cannes Film Festival in 1998, film critic Mark Kermode was removed from the venue for exclaiming, ‘Il est merde!’ He was responding less to the actual quality of the film, and more to its remarkably provocative and unsettling subject matter.

Lars von Trier, of course, thrives on such reactions. His aim is to disturb and unnerve, to stir the viewer out of his seat and out of his comfort zone. This is done not simply for the ‘shock value’ in itself, as there is no legitimate artistic worth in managing to provoke or enrage the audience; instead this is done in order to communicate something through the shocking material. By knocking the viewer out of his ordinary perspective, where everything is comfortably perceived and organized according to a familiar worldview, Lars von Trier can assault him with a new perspective, a new challenge that might threaten his old way of viewing reality.

Lars von Trier, of course, thrives on such reactions. His aim is to disturb and unnerve, to stir the viewer out of his seat and out of his comfort zone. This is done not simply for the ‘shock value’ in itself, as there is no legitimate artistic worth in managing to provoke or enrage the audience; instead this is done in order to communicate something through the shocking material. By knocking the viewer out of his ordinary perspective, where everything is comfortably perceived and organized according to a familiar worldview, Lars von Trier can assault him with a new perspective, a new challenge that might threaten his old way of viewing reality.

This is truer of The Idiots than any other LvT film, and that includes the psychological horror of Antichrist and the raw sexual trauma of Nymphomaniac. This is due to the highly abrasive nature of the film’s narrative, which tells the story of a group of people who act like they are mentally retarded as a form of rebellion against what they understand to be a constrictive, conformist, and sterilizing society. Their antics, which they call ‘spazzing,’ include going into town to sell Christmas ornaments that they have made, going to the pool to create mischief with the other swimmers, and eating at restaurants only to spazz and leave without paying.

It is during the last antic that the group comes into contact with Karen, a seemingly ordinary person who becomes drawn and intimately attached to the spazz community over the next two weeks. Karen initially provides the neutral perspective of the group, the backdrop of normality to their witting insanity; she is very curious, though, and constantly questions the reasoning behind their activities, allowing the viewer to get a keener understanding of what they do. She firstly represents the ignorant audience who nevertheless desire to know more, but later, as we will see, she represents the fulfilment of the ‘spazz way of life.’

The group is led by a man named Stoffer, who is clearly the one who takes their mission the most seriously, ostensibly giving it an ideological basis and a higher cause than merely acting like idiots. Karen asks Stoffer why they do what they do, and Stoffer replies, ‘In the stone age all the idiots died. It doesn’t have to be like that nowadays. Being an idiot is a luxury, but it is also a step forward. Idiots are the people of the future. If one can find the one idiot that happens to be one’s own idiot . . .’ Stoffer finds in idiocy an outlet for what bourgeois society has repressed or camouflaged, namely a kind of personal creativity that does not accord with social normalcy. It is a new freedom, one which was obviously unavailable in a more brutal time, but which is presently imperative in an era that prizes comfort, material luxury, and ostracizes everything that is not conducive to ‘making one’s way in the world,’ i.e., becoming rich and popular. Stoffer asks meaningfully, ‘What’s the idea of a society that gets richer and richer when it doesn’t make anyone happier?’ Stoffer’s idea is instead to make one happier regardless of riches.

The means of achieving this are chiefly to ‘find the one idiot that happens to be one’s own idiot,’ a demonstrably individualistic and interiorized path that cannot help but hearken back to the Dionysian nature of the Breaking the Waves heroine, Bess. The idea is to determine the other side of oneself, the side that society has dispelled and rejected from its embrace. It is in this sense that we are reminded of C. G. Jung’s conception of the ‘shadow,’ or the secret personality that is imbued with our darker elements, with everything that has been evicted from and cannot fit into conscious life. Stoffer’s aim is essentially to reconcile modern man with his shadow self in a radical way; he aims to reintegrate man with his inner darkness to create something that is once again whole, independent of outer definitions and social parameters. When one character wakes him up, telling him that another spazzer is breaking things on the property, Stoffer responds, ‘Sheds are bourgeois crap. Smashing windows is obviously part of Axel’s inner idiot.’ The smashing of windows is an act that is socially reprehensible, but, since it allegedly exists as part of Axel’s ‘inner idiot,’ his ‘shadow self,’ it is perfectly acceptable in spazzer society.

This opposition between consciousness and the shadow is present not only in the individual sense, where the characters play out this drama in themselves, but in the collective sense as well. What this means is that the bourgeoisie, which is invariably treated as a great evil and as something to be rebelled against, represents the conscious side, and the spazzer society represents the shadow side; they are the ‘reservoir of darkness’ that has spilled out from respectable society, and has come to life after society has failed to suppress it. They even use society’s own tools against it, inverting the logic of social machinations to serve immoral ends. In one scene, for example, Stoffer has one of the spazzers pretend to have tripped over a loose cobblestone near a well-to-do homeowner’s property, then pesters the man to pay them off in order to avoid a lawsuit. When the wealthy man asks whether the spazzer didn’t simply trip on his own rather than a loose stone, Stoffer answers, ‘Are you saying they drag their feet? that they are clumsy?,’ which forces the man to retreat, unwilling to be responsible for anything that might be considered ‘politically incorrect.’ Stoffer considers this to be a victory over the ‘fascist’ system that he hates, contemptuously gazing into its soul and mocking it.

There are other scenes, too, that reveal other ‘victorious’ moments against other, more typical members of society. The house where they are staying, for example, is that of Stoffer’s uncle, who has entrusted Stoffer to sell it. When he visits the house, he remarks that he take better care of it, saying that, ‘These floors have been waxed every day for fifty years,’ which of course exemplifies the hated bourgeois attitude. Later on, coming into possession of caviar, Stoffer shows his group how to ‘eat it the way they eat caviar in Soelleroed [their town],’ stuffing it into his mouth as though he were a child eating chocolate. Allured by the antics of her new friends, Karen also learns to spazz, and though she meaningfully does not participate to the same extent as the others, she says that, ‘We’re so happy here. I’ve no right to be so happy.’

II (Major Spoilers)

The ‘paradise’ of Soelleroed is largely an illusion, however, as the final third of the film reveals. It is in these segments that the real darkness of the shadow comes out, which altogether reflects the failure of Stoffer’s mission to reconcile it with their conscious lives. This is as manifest in Stoffer himself as in any of the others. In one scene, for instance, a city official arrives at the house to offer them a government grant and a new location where they might stay, somewhere that is further away from normal society and which therefore makes it harder for them to intrude upon normal people. Stoffer of course reacts violently to this, ripping off his clothes and chasing the official all the way back to town naked, screaming ‘Fascist! fascist!’ the whole time. The others drag him back to the house, but they have to physically restrain him, strapping him to a bed overnight as he has reverted to a purely irrational state, succumbing to an episode that was formerly merely an act.

Another character, too, after the girl he fell in love with is stolen away from the house by her father, chases after him, running into his car, gesturing wildly and speaking nonsense. Affected so deeply by his feeling for her, he is no longer able to bridge the gap between his conscious self and the primitive he used to play at but has now become reality. This is not a successful integration between consciousness and the shadow; this is the conquest of the former by the latter, resulting in the personality regressing to something animalistic and instinctual. Stoffer’s experimentation in human happiness has failed, because there is no longer anything human in his subjects.

There are more obvious instances of this darkness, too. After the night which Stoffer spends in straps, they have a party, and at the end of the party he requests a gangbang. Most of his fellows willingly participate, but some do not; this leads Stoffer and another to chase one of the unwilling women down, essentially raping her in a violently disturbing scene of spazz sex. It is significant that Karen retreats from this scene altogether, abstaining from the evil that has infiltrated the rest of the ‘shadow group.’ It is even more significant that she is not raped, for she has maintained her own sense of self in contradistinction to the others; her personality is still intact while those of the others have been overwhelmed and utterly ransacked of their humanity.

Nearing the end of the film, Stoffer comes to doubt the sincerity of his fellow idiots, suspecting that this is all just some sort of game to them. He orders them to play ‘spin the bottle,’ with whomever the bottle points at having to demonstrate his commitment to the cause by spazzing in ‘real life’ places such as at work or at home with the wife and kids. The first fails completely, refusing to spazz in front of his family; he elects a normal life instead of the idiot life and the mistress he kept among them. The second opts to spazz in front of an art class he will be teaching, but he fails as well, causing Stoffer to storm out of the class, saying, ‘You love this middle class crap. These old dames use more make-up than the national theatre.’ The teacher, Henrik, says, ‘I had no pride in my inner idiot.’ The shadow self was just an illusion for them, something to play at in an insubstantial expression of inward identity.

Stoffer himself comes no closer to the reconciliation between the shadow and the ego. Instead of being the romantic and anarchic hero revolting against the oppressive bourgeois system that he likes to consider himself, he is infact a representation of it in its inverted sense; he is the ‘other side of the same coin,’ reflecting the absence of a genuine morality that extends to both the ‘middle class’ and the bohemian individualism. His ethos is fundamentally the same as that of his bourgeois uncle: ‘In reality, the acceptance of the shadow-side of human nature verges on the impossible. Consider for a moment what it means to grant the right of existence to what is unreasonable, senseless, and evil! Yet it is just this that the modern man insists upon. He wants to live with every side of himself — to know what he is. That is why he casts history aside. He wants to break with tradition so that he can experiment with his life and determine what value and meaning things have in themselves, apart from traditional presuppositions’ (C. G. Jung, ‘Psychotherapists or the Clergy’).

Stoffer is the epitome of the ‘modern man’ in that he wants to throw off all social inhibitions, not merely those of the 20th Century middle class, but the entire framework of human society. His revolt is the same as the student and hippy revolts of the sixties, revolts which were ultimately codified into the same bourgeois vassals that they originally reacted against. This is what makes Stoffer the superficial counterpart to the bourgeoisie; this is what makes him its useful idiot.

Karen is the only one who volunteers to spazz in her own life. Taking along her friend Suzanne for company, Karen returns to her home, somewhere she has not been for two weeks. We soon learn that her son had died, and that her son’s funeral was the day after she joined the group. Her husband comes home, and they sit down to eat – and Karen drools and dribbles at her food, which causes her family to stare, and her husband to hit her. Suzanne takes her hand, and they leave together, smiling naively, innocently.

Earlier in the film, Karen says to Stoffer, ‘I just want to be able to understand why I’m here,’ to which he replies, ‘Perhaps because there is a little idiot in there that wants to come out and have some company.’ While that is true in a certain, limited sense, it is truer to say that Karen’s ‘little idiot’ needed to come out to save her conscious self. Besieged by an impossible grief and a mother’s mourning, Karen’s ego longed for an escape route from the world’s immense difficulty. That she alone found it amongst all the idiots testifies both to the extent of her trauma and her extraordinary capability of dealing with it; she alone could make real sense of what the idiots were only playing at. Their reactions (aside from Stoffer, who was overcome by his own shadow) were conditioned by their belonging to the bourgeois order, something from which they recoiled in theory, but which they nevertheless could not do without; Karen’s reaction, on the other hand, was conditioned by a more profound disorder, which demanded an extreme process in order to be able to cope with it. Her struggle was far more real than that of the others, which is why she was the only one to find the solution to it.

The Idiots reveals both the positive and the negative scenarios that are the consequence of a Dionysiac revolt against the Apollonian dream-world. In order to ‘revolt successfully,’ to truly indulge in Dionysian fruit, the individual’s actions must be founded on something universally real that transcends particular circumstances; he must determine himself based on who he really is rather than merely a perception or a projection of who he is. This is where most of the idiots failed: ‘The shadow is a moral problem that challenges the whole ego-personality, for no one can become conscious of the shadow without considerable moral effort. To become conscious of it involves recognizing the dark aspects of the personality as present and real. This act is the essential condition for any kind of self-knowledge’ (C. G. Jung, Aion). The idiots never really became conscious of their shadow; they acted it out either as a meaningless game that allowed them an illusion of rebellion against their bourgeois lives, or, in the case of Stoffer, as a license to perform whatever irrational and pernicious acts that occurred to him, as long as they did not agree with the prevailing social order. They never addressed the shadow as a ‘moral problem,’ as something that directly influences the person; they addressed it as a ‘social problem,’ and thus remained chained to the illusions of Apollo’s dream-world.

Karen alone represents Dionysus as the purveyor of dynamic, uninhibited truth. She refused the moral violations of the other idiots, she refused their pretensions of abandoning society, and she refused their needless and unlawful interdictions with the rest of the town; in a word, Karen rejected rejection, and she did so because her rebellion was founded on an affirmation of self rather than on its negation. Unlike Stoffer, who loses control when he is confronted with that which he hates and fears most (the bourgeois city official), Karen maintains perfect control as she releases her inner idiot in front of her family, again exemplifying a personal command that eluded the others.

Speaking of her return home, where she demonstrates her restored personal strength, she says to the idiots, ‘We’ll see if I can show you if it has all been worthwhile.’ This follows a farewell in which Karen expresses an open, authentic love for many of the idiots, and repeats her avowal of happiness to have been amongst them. Karen’s family, cold, unfeeling, and uncomprehending of what it must be for a mother to lose her son, failed to ease her grief; it was only in her introspection, the confrontation with her ‘inner idiot’ as a lifeboat that carries her from the drowning ego, that actually saves the ego. By acknowledging her despair in this radical context, she could dilute and eventually sublimate it into something far more positive, to the extent that, all things considered, she does not even know why or how she can be so happy. In this sense, the freedom of Dionysus is attained not as a rejection of Apollo, but as a victorious affirmation of the reconciliation between the unconscious and the conscious; while the rest of the idiots founded their shadow-search on a rejection of Apollo, Karen had to be rejected by him instead. This is what led to her final freedom; this is what made it all worthwhile.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

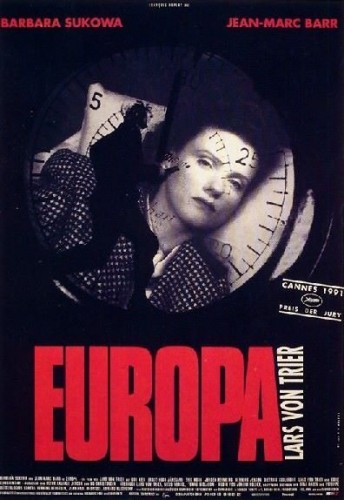

Europa is about a young American man born of German immigrants, Leopold Kessler, who travels to occupied Germany in late 1945, just a few months after the end of the war – an idealist and pacifist who, having deserted the American military during the conflict, now sees it as his mission to “show a little kindness to Germany” in order to “make the world a better place.”

Europa is about a young American man born of German immigrants, Leopold Kessler, who travels to occupied Germany in late 1945, just a few months after the end of the war – an idealist and pacifist who, having deserted the American military during the conflict, now sees it as his mission to “show a little kindness to Germany” in order to “make the world a better place.”