samedi, 21 mars 2009

The Social Vision of Valentin Rasputin

| |

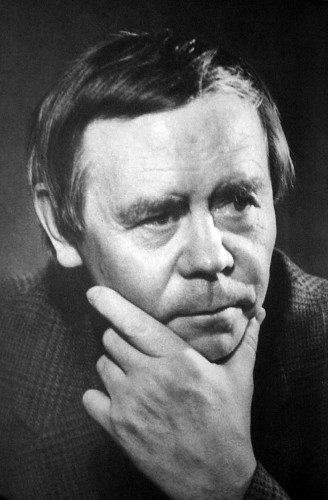

The Social Vision of Valentin Rasputin

by Matthew Raphael Johnson

In his own mind Rasputin may well be answering some such summons to be his own people’s medicine man for the purposes of understanding and cleansing that part of the world he calls home. –Harry Walsh

Soviet Marxism and Western Capitalism are nearly identical systems of rule. Where they differ is in the means of policy implementation. The USSR based its existence, clumsily, on a state apparatus. The west is far more sophisticated. It rules by a complex Regime: a matrix of private, state and semi-private capital, meshing together in advocating specific policies, appearing to be separate sources of power, but, in reality, offering a closed oligarchy of power, wealth and arrogance.

Nowhere is this identity of policy more obvious than in the realm of agriculture. Both capitalism and Soviet Marxism claim to be the bearers of Enlightenment values to mankind: modern Promethiuses, bringing the “transvaluation of all values” to a benighted herd. Both ideologies believe in progress and technology, which provides both with a distorted view of country and agrarian life. Both ideologies demand absolute conformity to its ideological dictates, even to the point of building global empires to impose such ideas. But insofar as the agrarian life is concerned, these ideologies are identical, considering this life “backward” and “inferior” to the technological paradise of urban living. Both ideologies demand, in short, either the eradication of country life (as in Lenin’s case), or its radical transformation (as in Khrushchev’s case). In Soviet Russia, modernization meant the state’s invasion of the agricultural sphere, demanding strict oversight and control of all agricultural programs, and encouraging migration to the cities. Urbanites were told to “enlighten” their “backward brethren” in rural areas into the socialist idea and the technological paradise that awaited them. Entire regions of arable land were annihilated through dam projects which flooded them, or nuclear fallout from tests, or environmental disasters responsible for the deaths of thousands.

In the west, as always, the policy is identical, the means very different. In 1999, the U.S. Department of Agriculture met with the two oligolopolists of the agrarian life–Archer Daniels Midland of Kansas City, and ConAgra of Omaha. Their purpose was the final destruction of the family farm and the parceling out of the abandoned arable to their corporate interests. In the meantime, major media was spewing the typical stereotype of rustics as hicks and morons, with pickup trucks and southern accents, “spittin’ tobacca’” and killing non-whites. It was and is an acceptable stereotype, according to the apostles of diversity, and one encouraged by everything from sitcoms to stand up comics. If one wants to sound stupid, merely speak in a southern accent. Media and corporate finance worked hand and hand to destroy agrarianism, small towns and the family farm.

The reality, of course, is that, from a political and moral point of view, the agrarian life is a threat. It is a threat to the Regime and its obsession with social control and Pavlovian manipulation. In Russia, it was not the Soviets who depopulated the countryside, by rather the “democratic reformers,” so beloved of Beltway lawyers. And it is within this context that the prose of Valentin Rasputin (b. 1937) needs to be understood, and cannot be understood without it.

The defenders of agrarianism are few and far between: Jefferson, Emerson, de Bonald and Rasputin largely exhaust the names. The Green movement in America, though occasionally assisting this cause, is funded almost exclusively by the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations, and contain, equally exclusively, Volvo-driving urbanites and suburbanites who might want to defend the “family farm” in theory, but despise actual rural people in reality. What the SUV-environmentalist crowd is actually doing in the name of “saving the family farm” is attacking rural hunters and ranchers (occasionally with state-sanctioned violence). The environmentalists have made their central policy ideas the attacks on hunting, ranching and logging, three major occupations of rural America. Whether the soccer moms see the absurdity is a matter of speculation, but the board of the Rockefeller Brother’s Fund fully is aware of it. The attack on rural life is both an ideological, as well as a class, battle. In the early 1990s, a common sight was turtle-neck clad suburbanites attacking poor, rural hunters in the name of “animal rights.” While only a few specialized outlets would touch stories like that, the clear class lines of the confrontations were obvious.

In the prose of Valentin Rasputin, many of these struggles make their appearance. Rasputin is largely loathed and ignored by the denizens of American literary criticism, and the published literature in English on his work numbers a whopping four articles. These range from the simplistic but informative “Conflicts in the Soviet Countryside in the Novellas of Valentin Rasputin” (by Julian Laychuk, published in the Rocky Mountain Review), to the very well done “‘Live and Love’: The Spiritual Path of Valentin Rasputin” (by Margaret Winchell, published in Slavic and East European Journal). The nature of Rasputin’s social vision is at the root of this obvious hostility.

For Rasputin, the dividing line of the 20th century is clear: it is between civilization and country; urban and rural; artificial and natural. Such a dividing line is common enough. His major works proceed in a basic and predictable style, more aimed at approaching an audience than explicating a genre. But this dividing line is always present, and it is what provides this writer with his strength and consistency.

The artificial world is that of civilization: regimented and fake. It is the world of ideology and power. The world of civilization is that of geometry, it is the Tower of Babel, where the worship of dead matter is the official religion. It recognizes only materiality, for materiality can be easily manipulated and controlled. It is elite by definition, for only an elite can even begin to understand the feats of engineering and mathematics that must be understood before the “marvels” civilization are manifest to the world. Reason is reserved to the elites, while the herd is controlled through their passions. The herd is accepting of technology because their “needs” are easily met by it, but at the price of their freedom and independence. But even more significantly, at the price of their identity.

But as the urban/civilizational life is based upon matter, the rural/rustic life is based on spirit. This is a rather complex notion in Rasputin, but is a notion that has a rather long history behind it. Spirit is not the opposite of matter, but is something hidden behind it, in the literal meaning of “metaphysics,” as something “behind” appearance. What science/urbanism can understand is solely what is can quantify , whether it be heat or velocity; votes or roubles. Matter is by its constitution quantifiable, and therefore controllable. Spirit is another matter, and is that aspect of material life that is non-quantifiable. Orthodox Christians can in no manner posit a radical opposition between spirit and matter, for it is precisely this confrontation that made up the “practical” backbone of the Synod of Chalcedon in 431. It is this distinction, that, at least at the time, made up the confrontation between Christian and Monophysite heresy. Matter and Spirit are two very different sides of the same thing. As vulgar Orthodox scholars like to reduce Chalcedon to a “quibble over language,” the reality is rather different, and goes to the heart of a Christian metaphysics.

In 18th century Ukraine, a now largely unread philosopher and metaphysician was active, Gregory Skovoroda. His mind was set to develop a Christian metaphysics, one that would do justice to the powerful insights of Chalcedon. Skovoroda is significant in understanding the nature of Spirit as manifest in the writings of Rasputin, and is able to distinguish Christian spirit from both the vulgar spiritualism of western “religion” and the materialism of the western economic world. One sentence might make sense of this: “This one is the outer frame, that one the body, this–the shadow, that–the tree, this–matter and that–the essence; that is the foundation sustaining the material mud just as the picture sustains its paint.” Though Skovoroda is distinct from Aristotle as he writes: “The universe consists of two essences: one visible, the other invisible. The invisible is called God. This invisible nature or God penetrates and sustains all creation and is and will be present everywhere and at all times.” While far from “materializing God,” such ideas (and they are difficult to being out in English) speaks of God as the Law of Law, or the Essence of Essence. Regularity and Law exist in the universe, and the ground of this regularity is God. Regularity and Law cannot exist without a Lawgiver by definition. While the Essence exists, the appearance, or the “material” side of this, is regularly changing. However, God is not purely imminent, but is so insofar as human beings can approach him. Objects the way out fallen and vulgar understanding picture them, are merely “shadows” cast by the Primal essence, or the Law of Law.

Objects partake of Law and Regularity, and that is the “divine” in them, object sub specie aeternis. Only the advanced ascetic can see objects in this manner. An object as it is, rather than as it appears. In the fallen world, objects/material are things for manipulation. They become objects, as Locke will argue, only to the extent that they are expropriated from their natural state. Humans too, can exist in either a natural or “expropriated” state. Objects exist to the extent to which man has rejected his empirical state of fallenness, and though the Orthodox life, through fasting and silence, can the Reality of being make an appearance. Objects do not them excite lusts, bur rather joy and contemplation.

Natural objects are “paths” to God, here. For they hide the reality of the Creator under their “accidents,” qualities that primarily strike the observer for only the fallen mind can appropriate these things. From this falseness, objects appear in a distorted way, as mere means for the domination of the gnostic elite over all nature through geometry. Ultimately, this is the genesis of empiricism and later capitalist democracy. Objects appear thus through the jaundiced lens of sin and fear of death. While Hegel argued that objects appear differently to different historical epochs, conditioned by specific ideas relative to such ears, Orthodoxy views the material world as changing through the specific “rung on the ladder” the ascetic finds himself on.

Skovoroda does not really require a “space” that is “beyond” the appearance of objects. Vulgar western religion has posited God “up, above” our material existence, existing in “heaven” that is “out,” somewhere “in space.” God then is a purely transcendent being, someone radically separate from his creation, and thus needs to be petitioned like a feudal lord. Of course, the patristic reality is different. God’s person is found as the eternal “idea” in creation, a part of it but far from identical with it. He is imminent in this sense, and is manifest to only the Orthodox ascetic through a life of self-denial, the slow emergence of the sprit struggle through the prison of false images cast by sin and fear. After the various western schisms, these religious bodies quickly lose this specifically imminent aspect of God. The papacy, then, in Protestantism, the individual will, was to take its place, until God became a mere philosopher’s phantom, without real being, without presence.

Once men begin the Christian struggle and receive “adopted sonship” through baptism, they become a living, empirical aspect of the Spirit’s activity on earth. Men do not pray in the sense they renew their driver’s licence (the Protestant view), but the Spirit communicates with Christ through their/our material agency. In other words, this metaphysics posits man/creation not radically separated from God, but simply unable to see His presence under the layers of filth caused by sin, the world and the Regime’s science. The Regime posits a globe of dead matter (including the cowans, i.e. non-initiated people, the herd) ripe for manipulation. Orthodoxy posits a material world that is bi-composite: one, comprising the qualities that Locke is convinced exhaust the matter of matter, and, two, the spirit, the Law of Law, or that aspect that permits matter to partake of Law and Regularity (without which there could be no science, good or bad). The life of asceticism permits the ascetic to begin to see and focus on the Law, rather than its quality, though Law through quality, rather than opposed to it.

Whether or not Rasputin regularly reads this great Ukrainian writer is another story, but in reading these novels, one can easily see the influence of the Chalcedonian metaphysic. For Rasputin, the urbanite cannot see the spirit underlying matter (so to speak). Everything in urban life, as all is conditioned by will, appears artificial, to be merely a bundle of qualities (i.e. substance-less). Men are no different, for to reduce them to a bundle of qualities is the only means of controlling them. Freedom, properly understood, derives solely through Orthodox asceticism; urbanism, therefore, must be based on indulgence, for indulgence, by building up the passions and their demands for satisfaction, permits for those who control access to such fulfillment full control over “human” or semi-human faculties. Urbanism destroys humanity; it destroy’s freedom by its very constitution and organization.

For Rasputin, particularly in his more recent labors, the purpose of life is to struggle to see, at least in outline, the basic spirit structures of the world. This can only be done in nature, outside of the distorted elite lense of urbanism. His characters experience mystical visions when in the outlands of Siberia, suggesting a knowledge that is beyond logic; a strange form of communication between Law and the psyche, one completely bypassed by modern geometry/logic. Such experience radically change these characters, bringing them to a knowledge of their identity and therefore, purpose. Rasputin’s epistemology is mystical, in that the mind is illumined through participation, a participation in Law, or a Reality that is only in a small way explicable through logic. The argument looks like this:

- P1: Modernity is based on quantification

- P2: Quantification is a quality adhering to extended matter

- P3: Extended matter, by definition, is not free, but is subject to manipulation

- C1: Therefore, Modernity is based on the manipulation of extended matter

- C2: Therefore, Modernity is based on unfreedom

- P4: Logic exists to assist in the manipulation of extended matter

- P5: Logic has no purpose other than being applied to matter and its behavior

- C3: Spiritual experience is therefore non-logical (super-logical).

- C4: Modern life can only see things that logic can manipulate

While this is incomplete, this argument makes a great deal of sense out of Rasputin’s writings, and the agrarian life specifically. Because of the nature of “participation,” (in the Platonic sense) Rasputin’s heroes/heroines, often are not specifically educated formally. They are people who have, so to speak, absorbed, through participation, the Reality of life. These are often older women, our babas or yayas, who, simply through experience outside of the logical/mathematical world of urban life, receive a great deal of wisdom, a wisdom outside of the experience of the urban life, a life that cannot absorb anything that is not based on the behavior of matter.

In modern life, the Slavic and Greek immigrant community that first built Orthodox life in North America is dying. Our babas/yayas are either dead or extremely elderly. In many parishes in America, the elderly are the only ones left, preserving some vague memory of the old country and a way of life radically alien to the American. They remain the last holdouts largely because of a specific form of cruelty and abuse, one specific to modernity, that is abandonment. But not a simple form of leaving home, but a sort of abandonment very different from that; it is a mental leaving of home.

My babas are still to be found among the Ukrainians of Lincoln, NE, holding down the parish of St. George with no more than 7 or 8 elderly members as of this writing (April 2007). These are the original Slavic immigrants to this part of the world. They came with nothing and built a small but extremely prosperous community. Needing no help from the Regime, the Ukrainian community in Lincoln and Omaha built a life based on the agrarian ideal of the small community, ethnic unity, religious devotion and limited wants. Media knew no role in their life. There were no TVs, and the music was either religious or folk. Coming to America not speaking English, being of an alien religion, and knowing nothing but persecution and suffering, these Ukrainins built prosperity and togetherness. In fact, to such an extent that they were able to finance several shipments of goods to Ukraine after the 1986 nuclear disaster, and were even involved with settling new immigrants and smuggling Christian literature into Ukraine. They burned their mortgage on that parish years early. They rarely contracted debts, and are now in retirement, enjoying a great deal of security.

Their children? A different story; a story of objective evil, failure and stupidity that can be summed up in two words: modernity and Americanization. These children have left the church and the community. They speak to their parents in the most smug of condescending tones, without a clue as to their virtues. The children have sought entry into corporate America, and, at best, have become groveling middle management bureaucrats, without identity, spirit or purpose. They watch the parish(es) that their parents built die of neglect, but have no difficulty in buying the SUV or spending $40 per tank of gas. They spout rehearsed slogans about democracy, as they vote for Clinton or McCain, while assisting in the destruction of real democracy, the autonomous ethnic community, financially and socially independent. They have abandoned the Ukrainian community and its church, while vegetating in front of the television, the chatroom or the ball game. These are survivors of both Soviet and Nazi Holocausts (some were married in the camps by secret clergy), but, oddly, no one cares; no one asks them how. No one asks about their experience, and they die in obscurity. Just down the street at my Alma Mater, the University of Nebraska, there are several scholars pretending to be Russia experts, and has one asked these survivors about their experience? Not one.

This is the vision of Rasputin. The elderly country woman as the ignored, spat upon bearer or wisdom. The spitter? The urbanite who abandoned the ancestral life for urbanism, the chance for power and money. The urbanite believes that formal education is the “magic elixir” that will transmogrify him or her from an ignorant bumpkin to a civilized member of the New Soviet Experiment, the 21st Century, or whatever. Returning to the village, smug and arrogant, the baba is simply considered an “old, pious fool,” but, as always, a fool who is far wiser than any urban bureaucrat, crammed into his minuscule apartment in the name of “success” and “progress.”

The baba is people centered; she is concerned with personality and simple yet profound moral lessons. The urbanite is institution centered. He is concerned with “progress” and “utility,” even “competitiveness.” Folklore is the center of the “people centered” baba, while ideology is the center of the “progress centered” urbanite. For the baba, decentralization is the key to freedom (though it is never articulated as such); while for the urbanite, it is centralization; oversight; control; coordination. These are the modern buzzwords. As always, the baba is the simple and unassuming (but strong) advocate of freedom and personality; the urbanite is the advocate of the machine and the institution; weak and dependent. Baba is strong and independent. Rasputin paints these colors in a strong but realistic contrast that is simply too much for the modern American literary critic to stomach. Many of us can see some of our own experience in Rasputin’s pages. My babas in Lincoln are powerhouses of knowledge, articulated in simple yet compelling forms. Their children have absorbed the latest fads from the major media, and thus appear as dependent, weak and childish (rather than child-like) shadows of their parents. For the babas, community and its values, codified in folklore, is the guide to life, for the urbanite, it is ultimately the ego, but an ego flattered by modern ideology and fashion.

Another writer has done an excellent job in getting to the heart of Rasputin’s work. In his article, “Shamanism and Animistic Personification in the Writings of Valentin Rasputin” (South Central Review, 1993), Harry Walsh brings out a few new insights into the agrarian vision through the prisim of ancient Shamanism. While Rasputin is Orthodox, his view of the ancient pagan “religion” of Russia is typical of my own: harmless customs that serve largely to humanize nature. These kinds of simple religion take natural reason and feeling as far as it can go in dealing with natural phenomenon without revelation. There are no “gods” in the Christian sense, but rather poetic fetishizations of either natural or social forces. It is precisely these customs and poetic “humanizations” that St. Innocent of Alaska strictly forbade his missionaries to interfere with as they were being evangelized into Orthodoxy. So long as these ideas did not interfere with the Christian faith, they were to be left alone.

Once of these sort of “personalizations” that comes out in Rasputin’s work is important to agrarianism and anti-modernism, and that is the “personification” of objects; that is, the personification of the land itself, and its common markers: rovers, mountains, leaves, colors and sounds. Here, as is commonly seen in Johann Herder, language is merged poetically with nature, with one’s surroundings. In herder’s case, thought is inconceivable without language (and thus historical experience), thought itself is merged within the natural world. The natural world is then a home. Contrary to the ravings of the gnostics and technophiles, nature is not an arbitrary creature, the creation of a semi-wicked demiurge that needs to be dethroned and “corrected,” but is a home, a life, it is not “other,” but an extension of one’s self. In Russian the noun “drug” means both “friend” and “other,” showing the slow merger of the two concepts. Of course, there is no “other” in friendship: the one is swallowed in the other. Friendship is precisely the swallowing of otherness, and a pleasant and voluntary absorption of otherness.

For the agrarian, the land is a person, in a sense. It is a loving mother that, all other things being equal, yield her bounty when she is treated with respect, no different than a loving wife. Is there a connection between modernity, abortion and the destruction of agrarian lifestyles? Of course. They are all really the same notion: the female, nature is desecrated and abused in the name of progress. As Francis Bacon wrote, “knowledge of nature” is “power.” Knowledge of nature is designed to keep her in submission, chained to the libidinous whims of the Lunar Society. Rape and industry have the same Baconian/Atlantean root. Therefore, agrarianism is seen as backward, as the male whoremonger is seen as macho and virile.

Nature in Rasputin is not merely to be preserved and loved as a mother/wife because she is pretty, or because she yields fruit. Both are important, but it goes deeper: nature is a mediator, of sorts, between man and God. The Orthodox vision of relics partakes in a limited way from this insight. Nature, to the sensitive, aesthetic and ascetic soul, contains the “fingerprints” of God in that it is regular, law governed, and sensitive to affection. It is not a difficult road from nature as law bearing, to nature as designed, to nature as the subject of a creator. The sensitive soul sees in nature tremendous beauty, order, proportion and the source of bodily life. How difficult is it to go from here to God as Beauty, Love and Provider? Even in the more disagreeable aspects of nature, such as snake’s venom, or cow dung, one can see the hand of the creator. Human beings, like it or not, eat that cow dong when we eat the products of the earth, that have been fertilized by it. Back in Nebraska, the farmers would tell the suburbanites holding their noses in the rural areas: “It smells like s**t to you; money and food to us.” They never quite had the heart to tell these benighted souls that they eat this fertilizer in every bite of a tomato or carrot.

For the agrarian, nature, the village, the trees and mountains are friends. They create a home. They are part of a larger community all bound together in love, a love at least partially manifested in the “law bearing” aspect of natural events. Science has never been able to understand that nature of regularity as such. Newton can understand it as a quality of matter, but as to its source, that’s another issue. Regularity is not something that adheres to objects, but itself must have a source. Regularity and law are the basis of science, and yet its source is purely in the realm of metaphysics and theology. Regularity and law are not the products of random events, but themselves are objects of scientific inquiry, and only a Law of Law, or the ground of law, can be responsible for order in a universe that tends to disorder and dissolution.

Yet, contrary to the myopia of modern positivism, poetry is the source of making a home out of natural objects. A home for the modern suburbanites is the McMansion thrown up in a few weeks by a builder making a quick buck, only soon itself to be sold in order to see a profit. Rasputin and the agrarian tradition see a home as a complex matrix, a matrix of sights and sounds, smells, people, colors and structures. Only a sensitive mind can “see” memories in an old barn, a careworn field, or an old tractor. The modern suburbanite cannot.

But taking this one step further, Dr. Walsh makes it clear that in Rasputin’s writings, these connections among objects, God, law, sense, memory (in the affective sense), loyalty, home, family, community, local institutions, etc., called by the ever misinterpreted Slavophiles “integral knowledge” automatically mean that man is a mediator, he is a mediator between the senses themselves (what philosophers sometimes call “intersubjectivity”); between logic and poetry; between sense and love; and most of all, between the living and the dead. Edmund Burke once famously called “tradition” the “democracy of the dead.” The traditions that hold rural communities together is not the creation of the present generation, but can only be the product of generations past, generations who suffered and struggled to make it possible for the present generation to be alive at all. The fact that the founders are now dead should have no bearing on their influence over the present. If one exists through the accident of birth, than why should the accident of death be a problem? Why should mere death be a barrier to influence? What is the moral ground for such an opinion? Should the dead vote? Yes, and it’s called tradition.

There are some modern philosophers who are slowly rejecting the concept of “I” in moral theory. Such a revolutionary opinion is almost inconceivable in modern post-revolutionary times. The “I” according to Oxford’s Derrick Parfit, should be reduced to “streams of experience” that do not admit of an ontological fundament. Such a notion is common enough for agrarianism and is found in Rasputin: the idea that the “I” is not a fundament, but is part of a larger reality. The ego is sunk into the integral basis of reality, but such a basis must be rather small (physically) and be based on a determinate community of people, region and language. The separation of the “I” from its surroundings is primarily an invention of the Roman empire and Stoicism, and is so well lampooned in Chekov’s Ward No. 6 The “I” is not a fundament, the community is, the integrity of one’s surroundings is. And it is on this basis that the personification of reality makes sense. Reality is absorbed by the community and transformed its social experience. And, further, it is this that makes capitalism and democracy so vile: for they see a forest as only so much wood, or as a potential field for development. The community, however, sees it as an ontological reservoir or feelings and memories; it is an aspect of personhood. The extreme emotions that sometimes are drawn out when old, rural settlements are bulldozed over for some trivial purpose is derived from precisely this ontological reality.

There is little doubt that Rasputin is a threat, and will remain so. As a fairly young man, he has several good years ahead of him. His work is accessible, and his message is clear. His characters are powerful and his personality uncompromising. Rasputin should have the role of the Solzhenitsyn of the 21st century, only it is not the Soviet GULAG that is the target, but the modern world and its sickness; the merger of corporate capital and Soviet repression.

| Home | Articles | Essays | Interviws | Poetry | Miscellany | Reviews | Books | Archives | Links |

00:20 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : lettres, littérature, littérature russe, lettres russes, russie, sociologie, politique, philosophie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les commentaires sont fermés.