“We will strike out against Bulgakovism!”[i]

And Bulgakov returned fire.

I would have preferred a title more along the lines of “Bulgakov Against Little-mindedness.” “Narrow-mindedness” maybe? But it seems to me, and I believe it seemed to him, that atheism is sufficiently synonymous with either.

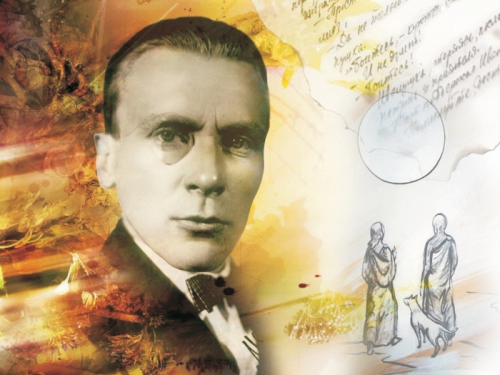

Mikhail Bulgakov is my favourite writer. My teacher—Headmaster of the school that I attend. I am assuming the reader will have read something by him. I won’t be providing a little biography of him of my own either. For that kind of a basic introduction, I confidently refer anyone interested to a good little article originally published in Russian Life entitled “Mikhail Bulgakov: A Wolf’s Life.”

Throughout the whole of his literary career Bulgakov thoughtfully engaged what was wrong in the society, and its thinking, in which he himself lived.

Where it went wrong in its thinking was official State irreligiousness, wishfully called “scientific atheism.”

Everything wrong in Soviet society stemmed out from there.

In his novels this is perfectly apparent. We’ll save the best known, Master and Margarita, for last. This will preserve an order both logical and chronological, as it was his final work and master-piece as well as his fullest attack on atheism and its allied ills.

In The White Guard the opinions of the Turbins over the table, with vodka and wine as encouragement, are very clear. The Revolution is destructive, idiotic and unwanted. The response in Kiev has been disgraceful, opportunistic and left it until too late. For free Ukraine “from Kiev to Berlin” there is only one option: “Orthodoxy and monarchy!”

Setting to one side Bulgakov’s feuilletons—written for bread, not to say something—we will look a little at the three major short-stories he wrote when in Moscow: Diaboliad, The Fatal Eggs and Dog’s Heart.

The Short Fiction

Diaboliad is best for its unique prose. It’s practice almost for the writer, the first flight, a getting used and accustomed to a new self-awareness and the exercise of a power not known prior. Margarita on her broomstick. Bulgakov before Diaboliad wanted to be a writer. When he wrote Diaboliad—he was.

Its protagonist loses his job, at the Main Central Base for Matchstick Materials (MACBAMM), in unbelievable circumstances and ends diving off of a building—an open question whether it was insanity, supernatural or just Soviet.

The atmosphere established is eerie. Bulgakov has already here located the absurd fact that Soviet society actually embodied what it denied. It may have consciously rejected the existence of the demonic, but the existence of such a society was itself proof of it.

The atmosphere established is eerie. Bulgakov has already here located the absurd fact that Soviet society actually embodied what it denied. It may have consciously rejected the existence of the demonic, but the existence of such a society was itself proof of it.

That is the major theme, tucked neatly under criticism of the housing situation and failures in economic policy. He is already creatively careful not to aim too openly at the target he really wants to hit. He will eventually have to summon up history, demonology, feign blasphemy and employ luxuriant symbolism to say everything he needs to.

Next came The Fatal Eggs. [Quick aside: it was originally published together with Diaboliad in May 1925]

A professor single-mindedly dedicated to his work has made a remarkable discovery. A ray that fantastically increases the rate of reproduction and the size of their off-spring in amphibians. A local journalist, with stereotypical sensationalism, publishes an article that misrepresents the discovery in a way most likely to hold the interest of his readers.

At just that time a disease decimates the poultry population of the USSR. An idiot has a bright idea—use the ray to produce excess, giant chickens to make up for the losses. The ray is taken from the professor and relocated to a rural area for the purpose.

A postal worker does his proverbial poor job and confuses two different loads of eggs. One has harmless chicken eggs and is intended for the ray. The other has a variety of unhatched serpents and is meant to arrive at the Institute where the professor works. It instead arrives at the farm.

The ray is then used to unintentionally produce an invasion of giant snakes that devastate the countryside. The civil authority and military are incapable of stopping them as they slither toward the capital. Humanly-speaking, all hope is lost.

But during the Dormition of Mother of God on the Orthodox Calendar (which Bulgakov continued to use even after the Soviet authorities had changed to the Gregorian), an unheard of frost, with no comparison available in even the oldest people’s memories, happens to kill them off. What a curious coincidence it was. And the reader’s attention is drawn to the dome of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour at just that moment in the narrative when Moscow is saved.

Here again we see the development, the birth and beginning of ideas which will find fuller expression later on in his work.

Isn’t this man imagining he can control his own life without reference to any higher order outside of himself? But Bulgakov has Providence provide a miracle that saves Moscow. Later on his mood has changed. Berlioz beheaded by a tram will serve to make the same point.

The main concern here is the belief, commonly held by people not Communists today, that science can essentially solve all problems. This simplistic idea tends to dangerous results when taken too far. We are slowly realising this. Bulgakov saw it in 1924. What disasters are in store if we don’t learn the lesson, God only knows.

And now we move onto the final major short-story —Dog’s Heart. Here the writer is too open, too incisive, his aim too obvious. It was never published for as long as he lived. And when at last it was, it was published abroad (in 1968).

It begins from the dog’s perspective, the stray Sharik. After lamenting his cruel fate, moments before having been scalded by a cook for stealing, an inordinate improvement in his luck follows. Professor Filipp Filoppovich takes him, takes care of him and treats him kindly. But there is a motive other than humane behind it all.

As an experiment Sharik’s scrotum and hypophysis are removed and replaced by human equivalents. He survives the operation and a most unusual result unfolds—he slowly becomes human.

As an experiment Sharik’s scrotum and hypophysis are removed and replaced by human equivalents. He survives the operation and a most unusual result unfolds—he slowly becomes human.

He begins to speak, becomes bipedal and eventually his personality merges with that of the deceased man whose testicles and pituitary gland he possesses.

Sharik changes his name to Polygraph Polygraphovich Sharikov and gets a job in the Moscow Department of Communal Welfare (for the extermination of cats and other foul rodents). Eventually entertaining a proletarian dislike for professor Filipp Filippovich, he avails himself of the easy-going informing policy of the Soviet government (not unlike present-day Kiev) to try and get him arrested. The professor’s hand forced, he manages to reverse the operation.

Here again we have science taken too far without sufficient thought given to the consequences liable to follow. But unlike professor Persikov of The Fatal Eggs—Filipp Filoppovich is a type as well as a character.

He is everything Bulgakov wished he could have been. A practising doctor with private customers and a large flat—safe through influential patients from any sudden moods of the government.

Characterised by class and taste, the professor is the exact opposite of the new Soviet man embodied in comrade Sharikov.

Bulgakov’s point is double-edged. It cuts twice with one stroke. That a dog made into a man could succeed in Soviet society and that ultimately the stray dog was better than the man it became.

There is furthermore an important insight into the cultural impact of an atheistic mind-set. In a society where the greatest goods are not religion or art or the humanities but rather manual labour and material possessions and creature comforts—the consequence is crassness.

The spoken-language deteriorates. So too what interests and amuses people. The public attention span dwindles. Everyone looks out for themselves and selfishness reigns. We have a dense, insensitive society where even such basic things as that seniority dictates who gets the first glass of vodka are lost.

And isn’t this timely now? Is it not perfectly applicable to the modern and Western situation?

We live in a time where people cannot work out how to use the past tense correctly or navigate the “th” sound. “Wif” and “dis” and so on.

Anything short of practically pornography or violence won’t stand a chance of selling or being aired.

A fast-food quality of intelligence now exists. You look at your phone, supposedly know in a snap-shot everything about something long enough to insist on your opinion about it and then promptly forget what you might have learned, comfortable in the knowledge that you can just Google it again if need be.

Do I need to provide any examples of selfishness reigning? I’ll dare not to.

Master and Margarita

Finally we come to the masterpiece.

Mikhail Bulgakov was a priest’s son, a professor at Kiev Theological Academy—Afanasy Ivanovich.

His death when the future writer was only 15 years old shook the boy’s faith in that God is Benevolent and All-knowing. But for Bulgakov conscious disbelief in the God of the Orthodox Church did not entail an a priori atheism, least of all of the simplistic and materialist kind sponsored by the Soviet State.

His death when the future writer was only 15 years old shook the boy’s faith in that God is Benevolent and All-knowing. But for Bulgakov conscious disbelief in the God of the Orthodox Church did not entail an a priori atheism, least of all of the simplistic and materialist kind sponsored by the Soviet State.

Why should there be no soul or spiritual world even if God as traditionally defined (admittedly altogether imperfectly) didn’t exist? That, for Bulgakov, did not follow.

In the years after he renounced his baptism up until he regained his faith in the God of his father he pursued different definitions and looked in the opposite direction to materialism, into spiritism. He was convinced that there was more to the universe than bare sensory phenomena.

And what could possibly justify the opposite claim? Could constitute positive proof that all that is, is necessarily material? And what of the numerous immediately obvious instances where it fails?

Concepts are not material, but they do exist. Materialism itself being one of them.

Individuals as persons are not material. Were I to lose a limb I would not be less Martin Kalyniuk than I was before.

Time exists I think. It isn’t material.

And it is not only this metaphysical cage that materialist atheists lock themselves in and throw away the key to. A moral narrowness follows on the mental one.

I repeat—in the master-piece the Master’s mood has changed. The devil is coming to Moscow. Not a swarm of snakes but the Serpent himself. The ancient one that began by exposing the infidelity of humanity’s parents to the God that made them. And he is back to expose and punish modern materialist man, with his closed mechanist universe and narrow pursuit of personal gratification.

It’s instructive that he begins with Berlioz. Berlioz’s crime is atheism. His denial that Christ existed in history, that God exists since eternity and his insistence that even Satan himself, who Berlioz is speaking with (!), does not exist either. We have to laugh with the devil.

Well, now, this is really getting interesting,” he cried shaking with laughter, “What is it with you? Whatever comes up you say doesn’t exist!

His punishment begins in time by the separation of his head from his body by a tram. It culminates in eternity when the devil gives him his wish.

Speaking to his severed, conscious head,

You were always an avid proponent of the theory that after his head is cut off, a man’s life comes to an end, he turns to dust, and departs into non-being. I have the pleasure of informing you in the presence of my guests—although they actually serve as proof of a different theory altogether—that your theory is both incisive and sound. However, one theory is as good as another. There is even a theory that says that to each man it will be given according to his beliefs. May it be so! You are departing into non-being, and, from the goblet into which you are being transformed, I will have the pleasure of drinking a toast to being!

Berlioz didn’t believe in life after death. Berlioz believed man is essentially a very complex material object. His final retribution is to be made into one, though a very simple one, a goblet, out of which a toast is made to the immortality he denied so vehemently.

Berlioz didn’t believe in life after death. Berlioz believed man is essentially a very complex material object. His final retribution is to be made into one, though a very simple one, a goblet, out of which a toast is made to the immortality he denied so vehemently.

And everyone is punished.

Laziness and fakery—Likhodeyev. Fraud—Nikanor Ivanovich. Generally being an annoyance—Bengalsky. Vanity—basically the whole female population of Moscow. Greed—everyone to a man. Spousal infidelity—Arkady Apollonovich. Blasphemy and cursing—Prokhor Petrovich. Covetousness—Maximilian Andreyevich. Informing and betrayal—Baron Maigel. And, the worst sin of all according to Bulgakov, cowardice—the cruel fifth procurator of Judea, the knight Pontius Pilate.

And what is most interesting above all, is that we feel nothing for them. Bulgakov has not invested any of them with pathos. They are not human beings. Not at all. Bulgakov has made them into what they wish to be—puppets. Mere material objects bumping into each other, with a pre-set selection of pursuits, wishes and desires as in a puppet-show.

They lack life. They have no depth. This is why Berlioz’s or Bengalsky’s head comes off and we don’t feel horror or revulsion. We may rather laugh. But we most certainly don’t bat an eyelid, leave aside shed a tear, between that occurrence and the sentence to follow.

And this narrowness of ideas and aims, shallowness of character and conduct, littleness of mind and heart are all the direct consequence and conclusion of the conviction that we are just finite, material toys trapped in time and space. Without purpose, without ultimate accountability and with no future beyond the short, uncertain span of our life on earth.

The ideas from the short-stories have been refined and sharpened. All the threads are drawn together, tight to breaking point—and Woland, Begemot, Koroviev, Gella and Azazello are here to cut them.

Man the material object meets spirit, even if evil. The atheist’s mechanical closed universe is invaded by beings that existed before it and who know of far more than it (the fifth dimension for example). And so far from being based on the empirical and experiential, so dogmatic is “scientific atheism” that Berlioz can try and convince the devil himself that he doesn’t exist.

This dogmatism of materialist atheism is the last point I should like underscore before closing this essay.

Fiction has the marvellous quality to it that you can’t argue with it. Like maths or a thought-experiment, you agree to play by rules. The cardinal rule is that what the narrator says is so. This gives the writer the power to make you think about things that you otherwise not for a single moment’s time would have entertained on your own.

Everything that has happened in Bulgakov’s Moscow—has happened. In the context of the novel, that’s a fact. “And” as the devil says to Berlioz’s head “a fact is the most stubborn thing in the world.” What do puppets do when confronted with them? Exactly what they do in actual life.

As always when something is reported that would seem to compel us to broaden our understanding of the way the world works—psychology is called in.

One person saw something exceeding a narrow understanding of the laws of the universe? He’s schizophrenic. Several people? Mass hallucination. And who’s responsible for the seeming events that didn’t occur? For everyone saw them, even if not a violation of the laws of nature.

“It was the work of a gang of hypnotists and ventriloquists magnificently skilled in their art.” ?!

Bulgakov’s final stab is his hardest. The way he wraps up the novel by providing naturalistic explanations that explain nothing but satisfy everyone and parade about behind the banners of scientific terms. There can be nothing more idiotic than these explanations. But how many people, during Bulgakov’s time, and, I stress, in the West today would readily venture or accept them if (or when) confronted with the same thing?

Could you believe that the devil exists? If one hot spring evening, just as the sun was going down, he sat next to you too?

[i] Ударим по булгаковщине!

(Title of an article published in a Soviet magazine during the writer’s lifetime and found among 297 other such collected articles in his private papers)

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.