Action, in the guise of movement, compelled by the impulse to perpetually overcome, forms the constituent basis of the underlying metaphysical superstructure of Europe. Action, in more exacting terms, is any act of will that elicits transformation, and the mutability of Europe is the key to its “Faustian” nature. One of the foundational pillars of Western civilization is its unique ability to modify itself and evolve, in essence to transform, via the espousal of a metaphysic of action as fluidic movement. European man, and the postmodern world to which he has given life in the crucible of Western civilization, arose in large part as a result of the active dynamism that radiates throughout the entirety of his being. The dynamism of “Faustian” Europe is based upon the principal of action, of explicit force, and of the striving for the realization of will made manifest for the purpose of transformation, of both our individual selves and the world in its totality.

Julius Evola, when speaking of action as expressed through the heroic, quite eloquently surmised both the nature of action and its ultimate telos of transfiguration as “being a sort of ritual evocation involving conquest of the intangible.”1 Thus it is the principal of action guided towards a perpetual striving for the intangible which, via the transfiguration of thought into form, is an externalized projection of the European soul onto the existential world. Action, made manifest and biological through the transgressive ontogenesis of European man, has endowed Western civilization with the capacity to act upon the world-historical stage in a manner that is directed, or willed, towards the orchestration of a unique historical agency that is unequivocally “Faustian” in character.

Julius Evola, when speaking of action as expressed through the heroic, quite eloquently surmised both the nature of action and its ultimate telos of transfiguration as “being a sort of ritual evocation involving conquest of the intangible.”1 Thus it is the principal of action guided towards a perpetual striving for the intangible which, via the transfiguration of thought into form, is an externalized projection of the European soul onto the existential world. Action, made manifest and biological through the transgressive ontogenesis of European man, has endowed Western civilization with the capacity to act upon the world-historical stage in a manner that is directed, or willed, towards the orchestration of a unique historical agency that is unequivocally “Faustian” in character.

The German intellectual Hans F. K. Günther defined the concept of race as being as “a [distinct] human group marking itself off from any other group through its own peculiar combination of bodily and mental characteristics,” and it was through the transformative power of action, mediated through the dynamism of a consciously willed historical agency made existentially manifest, that European man distinguished himself in stark contrast to other, less historically active, peoples.2 As such, action and the European ability to utilize action in the service of a Nietzschean will to transform, or “Will to Power,” has endowed European man with the singular power to direct the course of his biological, spiritual, and by extension his world-historical destiny. Modernity, and later postmodernity, is firstly a consequence of the intrinsic dynamism that underpins the European soul, and secondly the metaphysical culmination of the historical and sociocultural affirmation of the hegemonic role played by Europe and its people in the actualizing of the contemporary world. The brilliant French academic Pierre Manent describes modernity as a project, a movement whose aims are limitless and without end.3 A project presupposes action, and vis-à-vis the transformative effects of an action, the self-willed European man masters his destiny by the orientation of its direction. Manent, however, erroneously espouses that modernity is a gift bestowed by the West to the entirety of the world, whereas I would counter that it is rather modernity, as an action, as movement, and as a project indigenous to Europe and its global emulation by non-European peoples, whose collective inactivity has rendered them as mere historical actors, rather than agents, and which has veered the postmodern world towards the nebulous dogmatism of egalitarianism.

Egalitarianism, like all ideologies, is devoid of the contextual adaptability necessary for transformation, and it is thus intellectually inert. Nature is inherently inegalitarian, perpetually engaged in a process of active discernment between equality and inequality, between the equal and the unequal, whereas egalitarianism, by the nature of its lack of discernment and action, is passive, static, and antithetical to Nature. Aristotle’s statement that “…Justice is equality, but only for equals; and justice is inequality, but only for those who are unequal,” echoes the notion that the dialectical tension existing between equality and inequality is a matter of discernment animated by a constant reflective process, or action, directed towards the real, rather than the synthetic.4 The egalitarianism of the contemporary Western world is synthetic in the sense that it is based upon abstraction and the tragically convoluted conviction that opportunity and result are synonymous, rather than two requisite constituents of an active process of discernment. Inegalitarianism, by virtue of its intrinsic processes or actions of discernment, is an active movement geared towards the real rather than the ideal, evidenced by the fact that it’s not an abstract construct of the human mind, but rather a mirror image of the natural world. By logical extension, inegalitarianism, by the attributes of the active properties of its being, coupled with its relation to the natural world, makes it the natural paramour to the “Faustian” civilization of Europe.

Inegalitarianism, as an active process of discernment, is a movement of action, which in turn implies preference, or direction, and direction, or the ability to orient one’s self, or a civilization as a collective whole, is one of the defining characteristics of the dynamism of the West. As alluded to above, the historical agency of the West and of the unrivaled ability of its peoples to consciously will, or orient, the course of its civilization towards the actualization of a collectively ordained objective is the hallmark that has engineered Western hegemony. In sociology, the concept of “agency” is defined as an “entities’” (individual, collective, or otherwise) interaction with their unique social structure and the bidirectional reciprocity that ensures from this interactive relationship. The global and postmodern world is a project of European invention, a projection of our collective psyche made physical and metaphysical, and as such it cannot be mimicked by peoples who don’t possess the requisite biological or spiritual material necessary for its perpetuation. The failed attempt to reconceptualize postmodernity in universalist terms has catalyzed the ascendance of the egalitarian precepts that currently dominate Western civilization, and by virtue of its contraposition to the natural world and its connate passivity, has aided in the facilitation of a European world in decline. Evoking the wisdom espoused by Guillaume Faye in Archeofuturism, the co-option of our unique European cultural heritage, specifically the postmodernist project, is not only foolhardy, but unsustainable.5 In neo-Malthusian parlance, our civilization of scale and the resources necessary for its perpetuation, both of the material and immaterial variety, isn’t feasible at a globalized level. More relevantly, the legacy of Europe is a product of the zeal and active dynamism that animates the Western soul, and because it is a consequence of our unique history, it is the sole proprietorship of our people and cannot be replicated. Emulation implies stagnation, and this term is antithetical to the dynamism that propels Europe forward.

The impulse of vitality, the penchant for action, and the historical agency of the peoples of Europe has its origins in the ancient past, specifically in Homeric Greece. In Homer’s Iliad, Diomedes, the youngest, bravest, and the truest of the Achaeans brazenly states to his comrades who are about to give flight, “Don’t talk to me of retreat,” and it is within this simple turn of phrase that Homer captures the essence of the frenetic vitality of Europe.6 In the grand scheme of things, our ancestors never retreated, never relented, and never truly surrendered, because like the shark, we are constantly in motion, seeking to overcome ourselves and those forces inimical to our great becoming. The metaphysical basis underlying the action-oriented, heroic culture of Homeric Greece was founded upon the dualism inherent to life and death, of immortally and mortality, of activity and passivity, and thus upon the idea of the heroic, of the actionable in its truest and most pure form, and as such its praxis cannot be half-hearted. Moreover, one by definition cannot be only “a little” brave, and thus ancient Greece was a heroic culture of extremes and polarities, forged by a Weltanschauung that was founded upon the delicate balance, and in turn the dialectical synthesis, between life and death, or better as the perilous straddling of this synthesis. The purism of the thought and action of our heroic ancestors is best exemplified by the words of Julius Evola, who suggests that individuals should be oriented towards “acting without desire.”7 Action free from desire implies an organic synthesis of thought and action, whose “purity” is derived from the unity of the two seemingly discordant poles. Thus the works of Homer, which in reality were an enumeration of a much older oral tradition, was simultaneously both a reflection of early Greek culture and the literary medium for its glorification and perpetuation, a template, or as Dominique Venner phrased it, a “bible” of sorts, which would form the metaphysical impetus behind the later conquests of Alexander the Great, and by extension ancient Rome.

Although it was our Indo-European ancestors who first transcended the temporal plane, and sought prestige and status, the intangible rather than the material, it was within the culture milieu of the Greeks that this notion of the heroic life, of life atop the tip of the spear, was formally promulgated. The Greek concept of the heroic was inextricably intertwined with their notion of corporality, specifically with regard to their gods. The Theogony of the eight-century poet, Hesiod, whose works formed the basis of Hellenic religion, delineated in quite explicit terms the disjunction that existed between man and the divine, mainly that man is mortal, while the gods are not. From this notion, or realization, the Greeks codified a culture of the heroic, founded upon the principle that forceful, purpose-driven action, exuded not for riches or material gain, but rather for the immateriality of prestige, could be attained by besting their peers vis-à-vis the medium of combat, of competition based upon the pursuit of arête (Greek: excellence), in short by the personal transcendence that arises from a collective worldview which revolved around a dialectical centrifuge of life and death and the heroic. Heroism in this particular instance is not only the acknowledgment of death as an inevitability of the human condition, but also serves as a springboard from which only an elite few, those who faced death with an acute disdain for their mortality by the trials of combat, can transcend its finality by the attainment of the intangible and the immortality that emanates forth from glorious combat, from the ascesis of the struggle. As I articulated previously, the European penchant for the surpassing of space, the immaterial, and for infinity itself is a continuation of the love of arête, a passion for that which eclipses the ontic nature of the existential and surges towards the atemporal, the beyond.

It was in the works of Hesiod that the perspective of subjectivity, specifically the notion of the individual persona, entered into the Western literary tradition, and it was from this Hellenic literary tradition that the action of uniting the concepts of the individual and collective first entered into the transcendent soul of Europe.8 Hesiod’s elevation of subjectivity, combined with the visceral works of Homer, formulated the ideal that action, particularly within the context of the heroic, can only emerge through the cynosure of the individual deed. The genius of the Greeks, and their most munificent bestowal to Western civilization, was their remarkable ability to transmute individual action, and the social interactions generated from this individualized action, into collective action. It’s no coincidence that the eighth-century BC emergence of the polis (Greek: city-state) happened concurrently with the writing of the works both of Homer and Hesiod, and that the process of synoecism (Greek: joining together), of the demolishing of individual communities and their subsequent amalgamation into a larger, collective syncretization, formed the basis of both the polis and the “Faustian” soul of Europe. Walter Friedrich Otto, in his poetic masterpiece The Homeric Gods, speaks of the divine union of heaven and earth, representing the union of thought and action given form, when he references the works of the Greek tragedian Aeschylus and writes “of the amorous glow of ‘holy heaven’ and the nuptial yearning of Earth, who is impregnated by the rain from above” which is the metaphorical synthesis of the oneiric ethereality of the heavens and the collectivity of thought, synthesized with the externality of the Earth and manifested as individual action.9

It was in the works of Hesiod that the perspective of subjectivity, specifically the notion of the individual persona, entered into the Western literary tradition, and it was from this Hellenic literary tradition that the action of uniting the concepts of the individual and collective first entered into the transcendent soul of Europe.8 Hesiod’s elevation of subjectivity, combined with the visceral works of Homer, formulated the ideal that action, particularly within the context of the heroic, can only emerge through the cynosure of the individual deed. The genius of the Greeks, and their most munificent bestowal to Western civilization, was their remarkable ability to transmute individual action, and the social interactions generated from this individualized action, into collective action. It’s no coincidence that the eighth-century BC emergence of the polis (Greek: city-state) happened concurrently with the writing of the works both of Homer and Hesiod, and that the process of synoecism (Greek: joining together), of the demolishing of individual communities and their subsequent amalgamation into a larger, collective syncretization, formed the basis of both the polis and the “Faustian” soul of Europe. Walter Friedrich Otto, in his poetic masterpiece The Homeric Gods, speaks of the divine union of heaven and earth, representing the union of thought and action given form, when he references the works of the Greek tragedian Aeschylus and writes “of the amorous glow of ‘holy heaven’ and the nuptial yearning of Earth, who is impregnated by the rain from above” which is the metaphorical synthesis of the oneiric ethereality of the heavens and the collectivity of thought, synthesized with the externality of the Earth and manifested as individual action.9

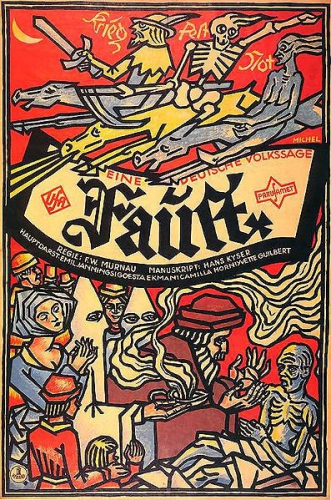

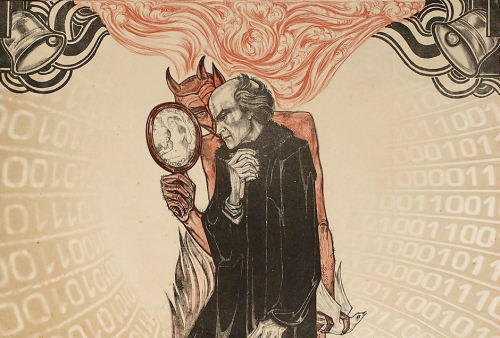

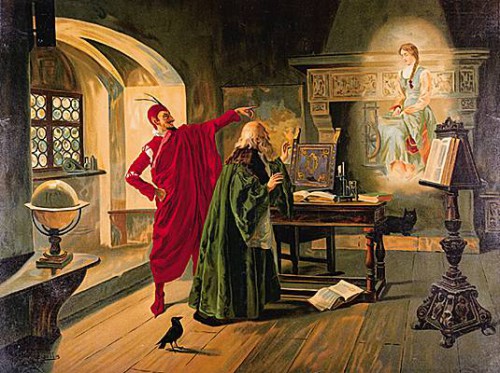

Thus, the genesis of the intrepid European spirit, of the “Faustian” nature of Western civilization derives from its desire to transform willed thought into action, of the Nietzschean sublimation of kraft (German: force) into macht (German: power), of action made incarnate. In Goethe’s Faust, most critics focus upon the eponymous protagonists’ pursuit of the unobtainable and immortality, however it is from the individual striving of Doctor Faust to achieve immortality that the term “Faustian” is best understood in its relation to the spirit of Europe. The individual actions of Doctor Faust, which strove towards a goal that was always just beyond the horizon and towards the intangible, expressed in literary terms the collective nature of Western, or “Faustian,” civilization and its yearning for action and the distant. It’s not the abortive dream of the attainment of immortality that so defines Doctor Faust, or metaphorically our “Faustian” civilization, but rather the action itself directed towards the attainment of immortality that defines who we are as a people. Thus, in more symbolic terms, the individualized actions of Doctor Faust are reflections of the collective nature of the European soul to overcome and transcend by transformation via action as a means for becoming. The action of overcoming the delimitations associated with the seemingly disparate notions of the “individual” and the “collective” ushered in the foundational basis of the “Faustian” spirit of Western civilization. Nietzsche wrote, “I say unto you: one must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star,” and the “radical aristocrats” of Greece, whose raison d’etre was the attainment of excellence, harnessed the chaos from within by means of a perpetual action of self-overcoming, which in turn fostered a Western culture of competition and the agon, ultimately birthing a European spirit that was “Faustian” in its desire for the unobtainable and tirelessly relentless in its pursuit. In the language of Martin Heidegger, and in contradistinction to the pure abstraction of Cartesian logic, existence is about becoming and about transforming concomitantly with the actions we take in the world, and our “Faustian” civilization is the earthly actualization of our metaphysical predilection towards the attainment of the unobtainable.

- Julius Evola, Metaphysics of War (London: Arktos Media, 2011), p. 18.

- Hans F. K. Günther, The Racial Elements of European History (Valley Forge, PA: Landpost Press, 1992), p. 6.

- Pierre Manent. Metamorphoses of the City (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013).

- Wilfried Hinsch, Gerechtfertigte Ungleichheiten: Grundsätze sozialer Gerechtigkeit (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2002), p. 91.

- Guillaume Faye, Archeofuturism: European Visions of the Post-Catastrophic Age (London: Arktos Media, 2010).

- Homer, The Iliad: The Verse Translation by Alexander Pope (North Charleston, SC: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2012), p. 122.

- Julius Evola, Ride the Tiger: A Survival Manual for the Aristocrats of the Soul (Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2003), p. 68.

- P. E. Easterling & Bernard M. W. Knox, The Cambridge History of Classical Literature: Greek Literature, Vol. I (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. 92

- Walter Friedrich Otto, The Homeric Gods: The Spiritual Significance Of Greek Religion (New York: Mimesis International, 2014), p. 36.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

The unique characteristics of Faustian civilization, as Spengler described it, are now leading Europe to destruction. The Faustian is characterized by a drive towards the infinite, a will to break through the boundaries that limit man, whether they be intellectual or physical. Spengler calls the prime symbol of the Faustian soul “limitless space.”[1] Like Goethe’s Faust, Faustian civilization seeks infinite knowledge.

The unique characteristics of Faustian civilization, as Spengler described it, are now leading Europe to destruction. The Faustian is characterized by a drive towards the infinite, a will to break through the boundaries that limit man, whether they be intellectual or physical. Spengler calls the prime symbol of the Faustian soul “limitless space.”[1] Like Goethe’s Faust, Faustian civilization seeks infinite knowledge.

Related to the Faustian tendency towards abstraction is the technical sophistication of Faustian civilization. Inventions spring from the unbounded Faustian mind. From the tools of abstract mathematics Faustian man has constructed the most precise and powerful theories of physical forces known to man. The combination of unlimited thought and dynamism enabled never before seen technological breakthroughs.

Related to the Faustian tendency towards abstraction is the technical sophistication of Faustian civilization. Inventions spring from the unbounded Faustian mind. From the tools of abstract mathematics Faustian man has constructed the most precise and powerful theories of physical forces known to man. The combination of unlimited thought and dynamism enabled never before seen technological breakthroughs.