The Pre-Death Thoughts of Faust

(1922 - #59)

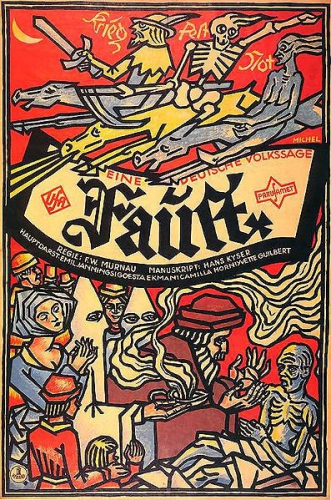

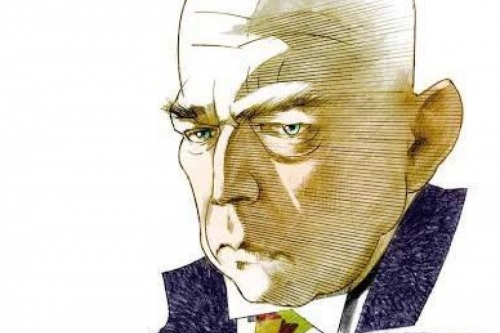

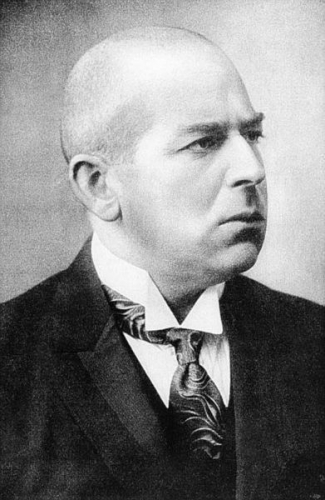

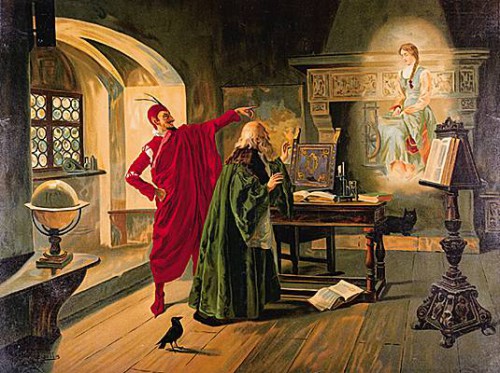

N. A. BERDYAEV (BERDIAEV)

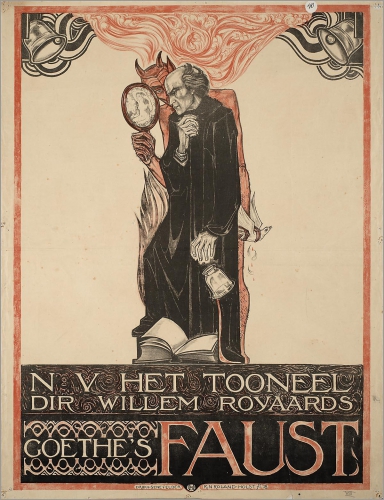

The fate of Faust -- is the fate of European culture. The soul of Faust -- is the soul of Western Europe. This soul was full of stormy, of endless strivings. In it there was an exceptional dynamism, unknown to the soul of antiquity, to the Greek soul. In its youth, in the era of the Renaissance, and still earlier, in the Renaissance of the Middle Ages, the soul of Faust sought passionately for truth, they fell in love with Gretchen and for the realisation of his endless human aspirations it entered into a pact with Mephistopheles, with the evil spirit of the earth. And the Faustian soul was gradually corroded by the Mephistophelean principle. Its powers began to wane. What ended the endless strivings of the Faustian soul, to what did they lead? The Faustian soul led to the draining of swamps, to the engineering art, to a material arranging of the earth and to a material mastery over the world. Thus we find spoken towards the conclusion of the second part of Faust:

Ein Sumpf zieht am Gebirge hin,

Verpestet alles schon Errungene;

Den faulen Pfuhl auch abzuziehn,

Das letzte waer das Hoechsterrungene,

Eroeffn ich Raeume vielen Millionen,

Nicht sicher zwar, doch taetig-frei zu wohnen.

Nigh the mountain a swamp doth stretch,

Pollutes there every advancement;

To drain off the foul pool,

Would be the utmost highest achievement,

I'd open up space for many a million,

Not indeed secure, but active-free to be.

And thus do end during the XIX-XX Centuries the searchings of the man of modern history. With genius Goethe foresaw this. But the final word for him belongs with the mystic chorus:

Alles Vergaengliche

Ist nur ein Gleichnis;

Das Unzulaengliche,

Hier wird's Ereignis;

Das Unbeschreibliche,

Hier ist's getan;

Das Ewig-Weibliche

Zieht uns hinan.

All the Transitory

Is but a Symbol Image

The Insufficient

Here doth transpire;

The Ineffable

Here doth act;

The Eternal-Feminine

Upward doth draw us.

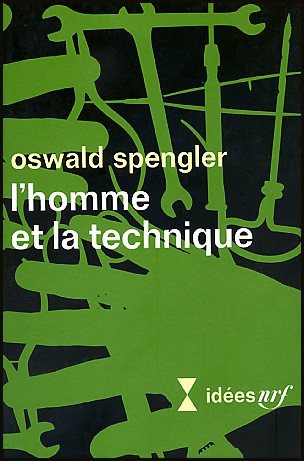

And draining the swamp is but a symbol of the spiritual path of Faust, merely a sign of spiritual activity. Upon his path, Faust passes from a religious culture over to an irreligious civilisation. And in this irreligious civilisation the creative energy of Faust becomes drained, his endless aspirations die. Goethe gave expression to the soul of Western European culture and its fate. Spengler, in his challenging book, "Der Untergang des Abendslandes" ["The Decline of the West"], announces the end of European culture, its ultimate transition over into civilisation, which is the beginning of the death-process. "Civilisation -- is the irreversible fate of a culture". The book of Spengler bears within it an enormous symptomatic significance. It conveys the feeling of crisis, of sudden impending change, that of the end of an entire historical era. It speaks about the great sorry affair of things in Western Europe. We, as Russians, have been split off from Western Europe already for many a long year, from its spiritual life. And since our access to it has been blocked, it has seemed to us to be more fortunate, more orderly, more happy, than it is in actuality. Even prior to the World War, I very acutely sensed the crisis of European culture, the impending end of an entire world era, and I expressed this in my book, "The Meaning of Creativity". During wartime also I wrote an article, "The End of Europe", in which I expressed the thought, that the twilight period of Europe has begun, that Europe is at an end as a monopolist of culture, that the emergence of culture out beyond the bounds of Europe has been inevitable, for other continents and other races. Moreover, two years back I wrote an etude, "The End of the Renaissance", and a book, "The Meaning of History: Attempt at a Philosophy of Human Fate", in both which I definitely expressed the idea, that we are experiencing the end of modern history, that we are living out the final remnants of the Renaissance period of history, that the culture of old Europe has tended towards deterioration. And therefore I read the book of Spengler with an especial tremulation. In our era, with its historical disintegration, thought is focused upon the problems of the philosophy of history. It was the same in the epoch, when Bl. Augustine conceived of his first rendering of a Christian philosophy of history. It is possible to foresee, that philosophic thought henceforth will be concerned not so much with problems of gnosseology, as rather by problems of the philosophy of history. In the "Bhagavad Gita" revelations occur during a time of warfare. During a time of war there can be resolved ultimate problems about God and the meaning of life, but it is difficult to get concerned over analytic gnosseology. And in out time is at work the thinking during a time of war. We live in an epoch inwardly akin to the Hellenistic epoch, the epoch of the collapse of the ancient world. The book of Spengler -- is a remarkable book, in places almost of genius, it stimulates and makes for thought. But it cannot be too much a surprise for those Russian people, who long since already have sensed the crisis, about which Spengler speaks.

* * *

Spengler can convey the impression of being an extreme relativist and sceptic. Even mathematics for him is something relative. There exists the ancient Apollonian mathematics, -- a finite mathematics, and there exists the European Faustian mathematics, -- an infinite mathematics. Science is not unconditional, not absolute, but is rather the expression of the souls of various cultures, of various races. But still, in essence, it is impossible to classify Spengler under any sort of current. Academic philosophy is quite alien to him, and he holds it in contempt. He is first of all his own unique individualist. And in this he is akin to the Goethean spirit of contemplation. Goethe intuitively contemplated the primal phenomena of nature. Spengler intuitively contemplates the history of the primal phenomena of culture. He, just also as with Goethe, is a symbolist as regards world-concept. He refuses to think employing abstract concepts, he does not believe in the fruitfulness of such thinking. All abstract metaphysics is foreign to him. From the morbid methodologism and gnosseologism, in which German great thought emerged, from the sick and futile reflection, Spengler has instead turned away towards living intuition. He casts himself into the dark ocean of the historical existence of peoples and penetrates into the soul of races and cultures, into the styles of the various epochs. He makes a break with the epoch of gnosseologism in the philosophy of thought, but he does not pass over to ontologism, he does not construct any sort of ontology and does not believe in the possibility of ontology. He knows only of being, as manifest in cultures, as reflected in cultures. The primal grounds of being and the meaning of existence remain for him hidden. The morphology of history for him -- is the solely possible philosophy. With him there is not even a philosophy of history, exclusively it is rather -- a morphology of history. All the truths, the truths of science, of philosophy, religion, -- are for Spengler merely the truths of culture, of cultural types, of cultured souls. The truths of mathematics -- are the symbols of various styles of cultured souls. Such an attitude towards cognition and being is characteristic to a man of a late and waning culture. The soul of a man set within an epoch of cultural decline tends to ponder over the fate of cultures, over the historical fate of mankind. It has always been so. Such a soul has no interest either in the abstract knowledge of nature, nor in the abstract knowledge of the essence and meaning of being. Of interest to it is the culture itself, and everything -- is merely reflected in the culture. It is struck by the dying off of once flourishing cultures. It is wounded by the inevitability of fate. Spengler is very capricious, he does not consider himself bound by anything in general obligatory. He is, first of all -- a paradoxicalist. For him, just as for Nietzsche, paradox is a means of cognition. In the book of Spengler there is a sort of affinity with the book of the youthful genius [Otto] Weininger, "Sex and Character", and despite all the different themes and spiritual outlook, the book of Spengler -- is just as remarkable a phenomenon in the spiritual culture of Germany, as is the book of Weininger. In breadth of intent, in scope, in its unique intuitive insights into the history of cultures, the book of Spengler can take its place alongside the remarkable book of [Houston Stewart] Chamberlain ("Die Grundlagen des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts" ["The Foundations of the Nineteen-Hundreds"]). After Nietzsche -- comes Weininger, Chamberlain and Spengler -- the sole genuinely original and remarkable figures in German spiritual culture. Just like Schopenhauer, Spengler has contempt for professors of philosophy. He offers a very arbitrary list of writers and thinkers, and in his opinion of the remarkable books, esteemed by him. These people are of a quite various a spirit. But they all bear some relationship to the principle of the will to live and the will to power, all have bearing on the crisis of culture. These are -- Schopenhauer, Proudhon, Marx, R. Wagner, Duhring, Ibsen, Nietzsche, Strindberg, Weininger. Is Spengler a pessimist? For many, his book has to produce the impression of a very boundless pessimism. But this is not a metaphysical pessimism. Spengler does not desire the quenching of the will to live. On the contrary, he desires the affirmation of the will to live and the will to power. In this he is closer to Nietzsche, than to Schopenhauer. All cultures are doomed to a withering away and death. Our European culture is also doomed. But it is necessary to accept fate, not oppose it, and to live it out to the end, and to the end manifesting the will to power. With Spengler there is the amor fati. The pessimism of Spengler, if such a term be properly applicable to him, is a pessimism culturo-historical, and is neither a pessimism individually-metaphysical nor individually-ethical. He -- is a pessimist on civilisation. He denies the idea of progress, and he returns to the teaching about cyclical returns. But with him there is no pessimistic balance of suffering and pleasure, of a pessimistic understanding of the very essence of life. He admits of an inexhaustible creative wellspring of life, lodged within the primal impulse, begetting culture all ever new and anew. He is fond of this will to cultural flourishing. And he perceives the death of a culture as a law of life, as an inevitable moment within the vital fate of a culture itself. Surprisingly strong with Spengler is a correlation of phenomena in various spheres of a culture and the discerning from them of an unique symbol, such as signifies that selfsame culture, that selfsame cultural style. He transfers concepts from mathematics and physics over into painting and music, from art into politics, from politics into religion. Thus, he speaks about an Apollonian and a Faustian mathematics. He discerns one and the same primary phenomenon within various epochs, within various cultures. And he regards it possible to admit of one and the same sort of such phenomena, as Buddhism, Stoicism and Socialism, belonging to various epochs and cultures. His most remarkable thoughts are about art and about mathematics and physics. And with him there are truly intuitions of genius.

Spengler -- is of an areligious nature. In this is his tragedy. With him there is as it were an atrophied religious sense. Whereas both Weininger and Chamberlain -- are of a religious nature, Spengler -- is areligious. He is not only himself non-religious, but he also does not understand the religious life of mankind. Yet he examined the role of Christianity within the fate of European culture. This -- is the most striking side of his book. In this is its spiritual deformity, almost its monstrous defect. It is not necessary to be a Christian, in order to understand the significance of Christianity within the history of European culture. The pathos of objectivity ought to be brought to bear on this. But Spengler does not sense himself under the compulsion of any such objectivity. He does not ponder on Christianity within history, he does not see a religious meaning. He knows, that culture is religious by its nature and by this it is distinct from civilisation, which is irreligious. But he has been able to express very noble thoughts, such as only can be expressed by a non-believing soul in our epoch. Behind his civilised self-feeling and self-awareness can be sense the imprint of a culture, which has lost its faith and is tending towards decline.

* * *

Spengler understands and senses the world foremost of all as history. This he regards as the modern perception of the world. It is only to such an attitude towards the world that there belongs a future. Dynamism is characteristic to our times. And only a perceiving the world as history is a dynamic perception. The world as nature is static. Spengler contrasts nature and history, as two methods of viewing the world. Nature is expanse. History is time. The world presents itself to us as nature, when we view it from the perspective of causality, and it presents itself to us as history, when we view it from the perspective of fate. That history is a matter of fate, is all very well and good with Spengler. Fate cannot be conceived of by means of a causal explanation. Only the perspective of fate gives us a grasp upon the concrete. Spengler's assertion is quite correct, that for ancient man there was no history. The Greek perceived the world as static, for him it was from nature, from the cosmos, and not from history. He did not know historical remoteness. Spengler's thoughts on antiquity are very insightful. And it mustneeds be admitted, that Greek thought did not know of a philosophy of history. It was not a matter of either Plato, or of Aristotle. The point of view of a philosophy of history is contrary to the aesthetic ponderings of the Hellene. The world for him was a completed cosmos. Hellenic thought created the Hellenic metaphysics, so inconducive for conceiving the world as an historical process. Spengler senses himself as an European man with a Faustian soul, with its infinite aspirations. He not only sets himself distinct from ancient man, he moreover asserts, that the ancient soul for him is inconceivable, is impenetrable. This however does not prevent him from drawing upon its understanding and insights. But does history exist for Spengler himself, is he one for whom there is a world, as history, and not as nature? I think, that for Spengler history does not exist and for him a philosophy of history is impossible. Not by chance did he call his book a morphology of world history. The morphological perspective derives from nature-knowledge. Historical fate, the fate of culture exists for Spengler only in that sense, that fate exists for a flower. The historical fate of mankind does not exist. There does not exist a single mankind, a single subject of history. Christianity was the first to have rendered possible a philosophy of history, in that it revealed the existence of a single mankind with a single historical fate, having its own beginning and end. Thus first for the Christian consciousness is revealed the tragedy of world history, the fate of mankind. Spengler however turns back to the pagan particularism. For him there is no mankind, no worldwide history. Cultures, races -- are isolated monads with an isolated fate. For him the varied types of culture experience a cyclical turning of their own fate. He returns to the Hellenic perspective, which was surpassed by the Christian consciousness. With Spengler the Baptismal water as it were was missing. He abjures his own Christian blood. And for him, just as for the Hellene, there does not exist the perspective of an historical remoteness. The historically remote distance exists only in this instance, if there exists an historical fate of mankind, a worldwide history, if each type of culture is but a moment of a worldwide fate.

The Faustian soul with its endless aspirations, with the distance opening up before it, is the soul of the Christian period of history. This Christianity shatters the boundaries of the ancient world, with its delimited and narrowed horizons. After the appearance of Christianity in the world, an infinity opened up. Christianity rendered possible the Faustian mathematics, the mathematics of the endless. Of this Spengler is not at all aware. He does not posit the appearance of the Faustian soul in any sort of connection with Christianity. He has made an examination of the significance of Christianity for European culture, for the fate of European culture. This fate however -- is a Christian fate. He wants to push Christianity back exclusively to the sense of a magical soul, to a type of Hebrew and Arabic culture, to the east. And he thus dooms himself to a lack of understanding of the meaning of European culture. For Spengler generally there does not exist a meaning to history. The meaning of history also cannot exist amidst such a denial of the subject of the historical process. The cyclical turnings of the various types of culture, lacking connections between them of a single fate, is totally meaningless. Moreover, the denial of a meaning to history makes impossible a philosophy of history. There remains but the morphology of history. But for the morphology of history there is merely the manifestation of nature, in it there is no unique historical process, no fate, as a manifestation of meaning. In Spengler the Faustian soul ultimately loses its connection with Christianity, which gave it birth, and in the hour of the waning of the Faustian culture it attempts to return to the ancient sense of life, tacking on it also the theme of history. In Spengler, despite his distasteful civilisation pathos, there is sensed also the exhaustion of a trans-cultural man. This weariness of a man of an era of decline quenches any sense of the meaning of history and its connections to historical fates. There remains only the possibility of an intuitive-aesthetic insight into the types and styles of the souls of cultures. Faust does not bear up under a time of historical fate, he does not want to experience it to the final end. He, weary and exhausted by the modern history, agrees it the better to die, having experienced a short moment of civilisation, set at the summit of culture. He is captivated by the thought, that he is to be given this final mitigation and consolation of death. But there is no death. Fate continues on even beyond this side of what the Faustian soul had acknowledged as the sole life. And the burden of this fate has to be carried across into the remote eternity. For Spengler's Faustian soul the remote eternity is hidden, the historical fate beyond the bounds of this life, of this culture and civilisation; to the end of his days he wants to restrict himself to the cycle of a dying civilisation. He foresees the rise of new cultures, which likewise will pass over into a civilisation and die. But these new souls of cultures are foreign to him and he regards them for himself as impenetrable. These new cultures which, perhaps, will arise in the East, will not have any sort of inward connection with the dying European culture. Faust loses the perspective of history, of historical fate. Culture for him -- is merely a springing forth, a blossoming and fading flower. Faust ceases to understand the meaning and the bond of fate, since for him the light of the Logos has grown dim, there has grown dark the sun of Christianity. And the appearance of Spengler, a man exceptionally gifted, at times close to genius in certain of his intuitions, is very remarkable for the fate of European culture, for the fate of the Faustian soul. There is nowhere further to go. After Spengler -- there is already the plunge into the abyss. With Spengler there is a great intuitive gift, but this -- is but the giftedness of a blindman. As a blindman, no longer still seeing the light, he throws himself off into the murky ocean of culturo-historical being. With Hegel there was still a Christian philosophy of history, in its sort no less Christian, than the philosophy of history of Bl. Augustine. It knows of an unified subject of history and meaning to history. It shines through everything with the rays of the Christian sun. With Spengler there are no longer these rays. Hegel belongs to a culture, possessing a religious basis; Spengler senses himself as already having passed over into a civilisation, bereft of religious basis. One might moreover still note, that the point of view of Spengler unexpectedly reminds one of the perspective of N. Danilevsky, as developed in his book, "Russia and Europe". The culturo-historical types of Danilevsky are very similar to the souls of the cultures of Spengler, but with this difference, that Danilevsky is quite lacking in the enormous intuitive gift of Spengler. Vl. Solov'ev criticised N. Danilevsky from the Christian point of view. For Spengler the fate of the history of the world remains unsolved, since for him history is but an aspect of nature, a phenomenon of nature, and it is not in that nature -- is an aspect of history, as it is for historical metaphysics.

* * *

Every culture inevitably passes over into civilisation. Civilisation is the fate, the doomed lot of culture. Civilisation however ends up by death, it is already the beginning of death, the exhaustion of the creative powers of a culture. This -- is a central thought of Spengler's book. "We are civilised people, and not people of the Gothic or Rococco". What differentiates civilisation from culture? A culture -- is religious as to its basis, civilisation -- is irreligious. For Spengler -- this is a fundamental distinction. And he regards himself as a man of civilisation, since he is irreligious. A culture derives from a cult, it is bound up with a cult of ancestors, it is impossible without sacred traditions. Civilisation is the will to worldwide might, to an ordering of the surface of the earth. A culture -- is national. Civilisation -- is international. Civilisation is the worldwide city. Imperialism and socialism alike -- are civilisation, and not culture. Philosophy and art exist only in a culture, in a civilisation they are impossible and unnecessary. Possible and necessary within civilisation is only the engineering art. And Spengler gives the appearances, that he understands the pathos of the engineering art. Culture -- is organic. Civilisation -- is mechanical. Culture is grounded upon inequality, upon qualities. Civilisation in contrast is pervaded by the aspiration for equality, it seeks to be based upon quantities. Culture -- is something aristocratic. Civilisation -- is something democratic. The distinction of culture in contrast to civilisation is of something extraordinarily fruitful. With Spengler there is a very acute sense of an inexorable process of the victory of civilisation over culture. The decline of Western Europe for him is first of all the decline of the old European culture, the exhaustion within it of the creative powers, the end of art, of philosophy, of religion. Civilisation has still not reached its finish. Civilisation will still celebrate its victory. But after civilisation will come the onset of death for the Western European cultural race. And after this, culture can blossom forth only in other races, only in other souls.

These thoughts are expressed by Spengler with an astounding brilliance. But are these thoughts something new? For us, as Russians, it is impossible to be taken aback by these thoughts. We long since already know of the difference of culture from civilisation. All the Russian religious thinkers have asserted this difference. they all sensed a certain sacred terror at the perishing of culture and the ensuing triumph of civilisation. The struggle against the spirit of philistinism, which so wounded Hertsen and K. Leont'ev, people of quite varied tendencies and outlook, was grounded upon this motif. Civilisation by its nature is pervaded by a spiritual philistinism, by a spiritual bourgeoisness. Capitalism and socialism entirely alike are infected by this spirit. Beneathe the hostility towards the West of many a Russian writer and thinker lies concealed not hostility towards Western culture, but rather hostility towards Western civilisation. Konstantin Leont'ev, one of the most insightful of Russian thinkers, loved the great culture of the West, he loved the colourful culture of the Renaissance, he loved the Catholic great culture of the Middle Ages, he loved the spirit of chivalry, he loved the genius of the West, he loved the mighty manifestation of the sense of person within this great cultural world. But he abominated the civilisation of the West, the fruition of the liberal-egalitarian process, the extinguishing of spirit and the death of creativity within civilisation. He comprehended already the law of the transition of culture over into civilisation. For him this was an inexorable law within the life of societies. Culture for him corresponded to that period in the developing of societies, which he termed as the period of the "blossoming of complexity", civilisation however corresponded to a period of "simplistic confusion". The problem of Spengler was quite clearly posited by K. Leont'ev. He likewise denied progress, he confessed a theory of cycles, he asserted, that after the complex blossoming forth of culture there ensues decline, decay, death. The process of "liberal-egalitarian" civilisation is the onset of death, of disintegration. For Western European culture he regarded this death as irreversible. He saw the perishing of the flourishing culture in the West. But he wanted to believe, that a flourishing culture was still possible in the East, in Russia. Though towards the end of his life he lost also this faith, he saw, that also in Russia civilisation was triumphing, that in Russia matters were going towards a "simplistic confusion". And then he came to be imbued with a dark apocalyptic outlook. So also Vl. Solov'ev towards the end lost faith of a possibility within the world of a religious culture and he had an anguished sense of the onset of the kingdom of the Anti-Christ. Culture is possessed of a religious basis, there is in it a sacred symbolism. Civilisation however is of the kingdom of this world. It is the triumph of the "bourgeois" spirit, of a spiritual "bourgeoisness". And it makes totally no difference, whether it be a civilisation capitalistic or socialistic, it is alike -- a godless philistine civilisation. Indeed even Dostoevsky was not an enemy of Western culture. Remarkable in this regard are the thoughts of Versilov in "The Adolescent". "They are not free, -- says Versilov, -- but we are free". "Only I alone in Europe with my Russian melancholy then was free... To the Russian, Europe is precious the same, as is Russia: each stone in it is dear and precious. Europe has been our fatherland the same, as also is Russia... O, to the Russian, dear are these old foreign stones, these miracles of God's old world, these bits of sacred wonders: and to us this is even more dear, than it is to them themselves. They have now other thoughts and other feelings, and they have ceased to appreciate the old stones". Dostoevsky loved these "old stones" of Western Europe, "these miracles of God's old world". But he, just as with K. Leont'ev, denounces the people of the West for this, that they have ceased to revere their "old stones", they have forsaken their own great culture and have surrendered themselves completely to the spirit of civilisation. Dostoevsky loathed not the West, not the Western culture, but rather the irreligious, the godless civilisation of the West. Russian Easternism, Russian Slavophilism was merely a veiled struggle of the spirit of a religious culture against the spirit of an irreligious civilisation. The struggle of these two spirits, of these two types, is innate to Russia itself. This is not a struggle of East and West, of Russia and Europe. And many Western people too have felt anguish, almost to the point of agony, at the triumph of the irreligious and monstrous civilisation over a great and sacred culture. Suchlike have been the romantics of the West. Suchlike were the French Catholics and symbolists -- Barbey d'Aurevilly, [Paul] Verlaine, Villiers de L'Isle-Adam, Huysmans, Leon Bloy. Suchlike was Nietzsche, with his anguish over the tragic Dionysian culture. Not only remarkable Russian people, but also the most refined and perceptive Western people with anguish felt, that the great and holy culture of the west was perishing, that it was dying, that coming to it was a civilisation alien to it, a worldwide city, irreligious and international, that a new sort of man was coming, a parvenue, obsessed with a will to world power and taking possession of all the earth. In this victorious march of civilisation was dying the soul of Europe, the soul of European culture.

The originality of Spengler was not in the positing of this theme. This theme had already been posited with an extraordinary alacrity by Russian thought. The originality of Spengler lies however in this, that he has no desire to be a romantic, he does not wish to anguish over the dying great culture of the past. He wants to live in the present, he wants to accept the pathos of civilisation. He wants to be a citizen of the worldwide city of civilisation. He preaches a civilisation's will to world power. He is consentual to trading off religion, philosophy, art for technology, for the draining of swamps and the erecting of bridges, for the invention of machines. The uniqueness of Spengler lies in this, that there has not been yet a man of civilisation, a drainer of swamps, endowed with such an awareness as with Spengler, a sad awareness of the inexorable decline of the old culture, endowed with such a keenness and such a gift of penetration into the culture of the past. Spengler's self-feeling for civilisation and his self-awareness are at the root contradictory and ambiguous. In him there is not civilisation's arbitrary sense of value and self-smugness, there is not that faith in the absolute excellence of its own epoch, of its own generation over all the epochs and generations that went before. It is impossible to construct a civilisation, to defend the interests of a civilisation, to dry up swamps with such a mindset as Spengler has. For these deeds what is necessary is a dulling of consciousness, becoming thick-skinned, with a naive faith in the endless progress of civilisation. Spengler tends to understand everything too well. He is not the new man of civilisation, he is rather, the dying Faust -- the man of the old European culture. He -- is a romantic in an era of civilisation. He wants to give the appearance, that he is interested by the engineering art, by the draining of swamps, by the erection of the world city. In actuality, he writes instead a remarkable book about the decline of European culture and by this he works a deed of culture, rather than of civilisation. He is as such unusual a cultural man, overwhelmingly a cultural man. Such people tend poorly to build the world city of civilisation. They are better at writing books. Faust hardly can be called a fine engineer, a fine maker of civilisation. He is dying at the very moment, when he decides to set about the draining of swamps. Spengler is not a man of civilisation, as he wants both himself and us to believe, - he is a man of a late and declining culture. And therefore in his book is discerned the evidence of grief, foreign to a man of civilisation. Spengler -- is a German patriot, a German nationalist and imperialist. This is clearly expressed in his booklet, "Preussentum und Sozialismus" ["The Prussian and Socialism"]. In him there is the will to world power for Germany, there is the faith, that during the period of civilisation, such as still remains for Western Europe, this world power of Germany will be realised. He combines with civilisation this will and this faith for himself, he finds for himself a place within it. But the history of recent years has inflicted such a blow to the imperialistic mindset of Spengler. If imperialism and socialism -- be not one and the same thing, then -- certainly, Spengler is moreso the imperialist, than a socialist. The civilisation of a world city however is beginning to move more rapidly in the direction of realisation of a world power and world kingdom, the kingdom of this world, through socialism, rather than through imperialism.

* * *

Our era has features of affinity with the Hellenistic era. The Hellenistic era brought to an end the culture of antiquity. And, according to the thought of Spengler, this was a transition of the culture of antiquity over into civilisation. Suchlike is the doomed lot of every culture. And for both our era and for the Hellenistic era alike there is characteristic the mutual interaction of East and West, the meeting and coming together of all cultures and all races, a syncretism, the universalism of civilisation, the feeling of an end-time, the demise of an historical era. And in our era too the civilisation of the West turns towards the East and the trans-cultural people of this civilisation seek for light from the East. And in our era too within the various theosophic and mystical currents there occurs the jumbling together and combining of various systems of beliefs and cults. And in our era too there is the will towards a worldwide uniting in imperialism and the selfsame will finds expression also in socialism. Cultures and states cease to be nationally isolated. The individuality of the cultures passes over into the universality of civilisation. And in our era too there is the thirst to believe and a powerlessness to believe, a thirst to create and a powerlessness to create. And in our era too there predominates an Alexandrianism both in thought and in creativity. Within history daylike and nightlike eras follow in succession. The Hellenistic era was a transition from the daylight of the Hellenic world over to the night of the Medieval Dark Ages. And we stand at the threshhold of a new night era. The daytime of modern history is at an end. Its rational light is dying down. Evening ensues. And it is not Spengler alone who sees the signs of the encroaching twilight. Our time in many of its portents is reminiscent of the beginning of the early Middle Ages. The have begun the processes of drawing back and consolidation, similar to the processes of drawing back and consolidation during the time of the emperor Diocletian. And it is not so improbable an opinion, to imagine that there is beginning a feudalisation of Europe. The process of the collapse of states is transpiring parallel to an universalistic uniting. There are occurring enormous transmigrations and displacements of masses of mankind. And there will perhaps ensue a new chaos of peoples, from which nowise quickly will a new orderly cosmos take shape.

The World War has drawn Western Europe out of its customary, its established boundaries. Central Europe lies inwardly devastated. Its powers not only materially, but also spiritually, have become overstrained. Civilisation through imperialism and through socialism has to pour forth across the surface of all the earth, has to move even towards the East. Into the civilisation will be brought ever new masses of mankind, new segments. But the new Middle Ages will be a civilised barbarism, a barbarism amidst machines, and not amidst forests and fields. The great and sacred traditions of culture will turn inward. The true spiritual culture, perhaps, will happen to experience a catacomb period. The true spiritual culture, having survived its Renaissance period, having gone through its humanistic pathos, will happen to return to certain principles of a religious medieval culture, not a barbarian Middle Ages, but rather a cultural Middle Ages. Upon the pathways of the modern, the humanistic, the renaissance history, everything is already exhausted. Faust upon the paths of an outward endlessness of aspirations exhausted his powers, he wore down his spiritual energy. Still, there remains for him movement towards an inner infinity. In one of his aspects, Faust has had to totally surrender himself over to the external material civilisation, a civilised barbarism. Though in another of his aspects he has to be faithful to the eternal spiritual culture, the symbolic existence of which was expressed by the mystical chorus at the finish of the second part of "Faust". Suchlike is the fate of the Faustian soul, the fate of European culture. The future is twofold. With Spengler, the preeminence of spiritual culture is sundered. It passes as it were over totally into civilisation and dies. Spengler does not believe in an abiding meaning to world life, he does not believe in the eternal aspect of a spiritual reality. But even if spiritual culture should perish amidst the quantities, it then still will be preserved and abide amidst the qualities. It was carried forth both through the barbarity and night of the old Middle Ages. It will be carried forth also through the barbarity and night of the new Middle Ages, prior to the dawn of a new day, to a coming Christian Renaissance, when there will appear the St. Francis and the Dante of the new epoch.

* * *

The truths of science for Spengler are not independent truths, but are rather truths relevant of the culture, of cultural styles. And the truths of physics are connected with the souls of a culture. There is a very remarkable chapter about the Faustian and Apollonian nature-knowledge. Mighty strides in physics have been characteristic of our era. Within physics there is occurring a genuine revolution. But the discoveries, which the physics of our era is uncovering, are characteristic of the decline of a culture. Entropy, connected with the Second Law of Thermodynamics, radioactivity and the decaying apart of atoms of matter, the Law of Relativity -- all this tends to shake the solidity and stability of the physico-mathematical world-perception, and it undermines faith in the lasting existence of our world. I might say, that all this -- represents a physical apocalypsis, a teaching about the inevitability of the physical end of the world, the death of the world. Only during the era of the waning of European culture does there arise such an "apocalyptic" disposition within physics. What a difference it is from the physics of Newton. Newton in his physics did not give his own interpretation of the Apocalypsis. The physics of our day can be termed the pre-death thoughts of Faust. It has become impossible to seek for stability in the physical world order. Physics posits a death sentence for the world. The world is perishing in its proportionate discharge of warm energy into the universe, of energy, unreturnable into other forms of energy. The creating energies at work in forming the manifold of the cosmos, are subsiding. The world is perishing from an irreversible and insurmountable striving towards physical equilibrium. And is not the striving towards equilibrium, towards equality, in the social world that same sort of entropy, that same ruination of the social cosmos and culture in a proportionate discharge of warm energy, unreturnable in any sort of energy as is creative of culture? A pondering over the themes, posited by Spengler, leads to these bitter thoughts. But the bitterness of these thoughts ought not to be inescapable and gloomy. Not only physics, but also sociology, do not have belonging to them the final word in deciding the fates of the world and of man. The loss of a physical stability is not an irreversible loss. It is in the spiritual world that it is necessary to seek for stability. It is in the depths that it is necessary to seek for points of support. The world as external lacks infinite perspectives. The absurdity within it has been shown over the ages. But there is apparent an infinite inner world. And it is with it that there ought to be connected our hopes.

* * *

In the large book of Spengler nothing is said about Russia. Only in the table of contents of the projected second volume is there a final chapter entitled -- "Das Russentum und die Zukunft" ["The Russian and the Future"]. There are grounds to think, that Spengler sees in the Russian East that new world, which will come to replace the dying world of the West: in his booklet "Preussentum und Sozialismus" several pages are devoted to Russia. Russia for him -- is a mysterious world, incomprehensible for the world of the West. The soul of Russia is still more remote and ungraspable for Western man, than is the soul of Greece or of Egypt. Russia is an apocalyptic revolt against antiquity. Russia -- is religious and nihilistic. In Dostoevsky is revealed the mystery of Russia. In the East can be expected the appearance of a new type of culture, of a new soul of culture. Yet this too contradicts the suggestions about Russia as a land nihilistic and hostile to culture. In the thoughts of Spengler, ultimately not followed out to the end, there is a sort of something turned backwards, where its opposite end seems an assertion of Slavophilism. And for us these thoughts are of interest, this turning of the West towards Russia, these expectations, connected with Russia. We are situated in more propitious a position, than is Spengler and the people of the West. For us the Western culture is attainable and graspable. The soul of Europe does not represent for us a soul remote and incomprehensible. We are in an inner communion with it, we sense in ourselves its energy. And yet at the same time we are the Russian East. Therefore the scope of Russian thought has to be broader, from its apparent remoteness. The philosophy of history, towards which the thought of our era turns, with great success has to be worked out in Russia. The philosophy of history always was of a basic interest within Russian thought, beginning with Chaadayev. That, which we are experiencing at present, ought ultimately to lead us out of our isolated existence. Granted that at present we are still moreso pushed back eastwards, but at the end of this process we shall cease to be the isolated East. Whatever happens with us, we inevitably have to emerge onto the world stage. Russia -- is at the middle between East and West. In it clash two torrents of world history, the Eastern and the Western. In Russia is hidden a mystery, which we ourselves cannot fully fathom. But this mystery is connected with a resolving of whatever the themes of world history. Our hour has still not come. It will be connected with the crisis of European culture. And therefore such books, as the book of Spengler, cannot but excite us. Such books are closer to us, than to the European peoples. This -- is our style of book.

Nikolai Berdyaev.

(1922)

© 2003 by translator Fr. S. Janos

(1922 - 59,1 -en)

PREDSMERTNYE MYSLI FAUSTA. Berdyaev's article is the 3rd of a four part anthology, "Osval'd Shpengler i Zakat Evropy", first published by book-publisher "Bereg" 1922, Moscow, p. 55-72. This entire 1922 Oswald Spengler anthology has been included in the V. V. Sapov edited Berdyaev-reprint under the partially inclusive title, "Smysl Istorii; Novoe Srednevekov'e", Publisher "Kanon", 2002 Moscow, p. 312-404; the Berdyaev title p. 364-381. (The other three selections included in this Spengler anthology are: F. Stepun -- "Osval'd Shpengler i 'Zakat Evropy'", S. Frank -- "Krizis zapadnoi kul'tury", Ya. Bukshpan -- "Nepreodolennyi ratsionalizm".

Е-текст по-русский: Кротова ..

Return to Berdyaev Online Library..

Julius Evola, when speaking of action as expressed through the heroic, quite eloquently surmised both the nature of action and its ultimate telos of transfiguration as “being a sort of ritual evocation involving conquest of the intangible.”1 Thus it is the principal of action guided towards a perpetual striving for the intangible which, via the transfiguration of thought into form, is an externalized projection of the European soul onto the existential world. Action, made manifest and biological through the transgressive ontogenesis of European man, has endowed Western civilization with the capacity to act upon the world-historical stage in a manner that is directed, or willed, towards the orchestration of a unique historical agency that is unequivocally “Faustian” in character.

Julius Evola, when speaking of action as expressed through the heroic, quite eloquently surmised both the nature of action and its ultimate telos of transfiguration as “being a sort of ritual evocation involving conquest of the intangible.”1 Thus it is the principal of action guided towards a perpetual striving for the intangible which, via the transfiguration of thought into form, is an externalized projection of the European soul onto the existential world. Action, made manifest and biological through the transgressive ontogenesis of European man, has endowed Western civilization with the capacity to act upon the world-historical stage in a manner that is directed, or willed, towards the orchestration of a unique historical agency that is unequivocally “Faustian” in character.

It was in the works of Hesiod that the perspective of subjectivity, specifically the notion of the individual persona, entered into the Western literary tradition, and it was from this Hellenic literary tradition that the action of uniting the concepts of the individual and collective first entered into the transcendent soul of Europe.8 Hesiod’s elevation of subjectivity, combined with the visceral works of Homer, formulated the ideal that action, particularly within the context of the heroic, can only emerge through the cynosure of the individual deed. The genius of the Greeks, and their most munificent bestowal to Western civilization, was their remarkable ability to transmute individual action, and the social interactions generated from this individualized action, into collective action. It’s no coincidence that the eighth-century BC emergence of the polis (Greek: city-state) happened concurrently with the writing of the works both of Homer and Hesiod, and that the process of synoecism (Greek: joining together), of the demolishing of individual communities and their subsequent amalgamation into a larger, collective syncretization, formed the basis of both the polis and the “Faustian” soul of Europe. Walter Friedrich Otto, in his poetic masterpiece The Homeric Gods, speaks of the divine union of heaven and earth, representing the union of thought and action given form, when he references the works of the Greek tragedian Aeschylus and writes “of the amorous glow of ‘holy heaven’ and the nuptial yearning of Earth, who is impregnated by the rain from above” which is the metaphorical synthesis of the oneiric ethereality of the heavens and the collectivity of thought, synthesized with the externality of the Earth and manifested as individual action.9

It was in the works of Hesiod that the perspective of subjectivity, specifically the notion of the individual persona, entered into the Western literary tradition, and it was from this Hellenic literary tradition that the action of uniting the concepts of the individual and collective first entered into the transcendent soul of Europe.8 Hesiod’s elevation of subjectivity, combined with the visceral works of Homer, formulated the ideal that action, particularly within the context of the heroic, can only emerge through the cynosure of the individual deed. The genius of the Greeks, and their most munificent bestowal to Western civilization, was their remarkable ability to transmute individual action, and the social interactions generated from this individualized action, into collective action. It’s no coincidence that the eighth-century BC emergence of the polis (Greek: city-state) happened concurrently with the writing of the works both of Homer and Hesiod, and that the process of synoecism (Greek: joining together), of the demolishing of individual communities and their subsequent amalgamation into a larger, collective syncretization, formed the basis of both the polis and the “Faustian” soul of Europe. Walter Friedrich Otto, in his poetic masterpiece The Homeric Gods, speaks of the divine union of heaven and earth, representing the union of thought and action given form, when he references the works of the Greek tragedian Aeschylus and writes “of the amorous glow of ‘holy heaven’ and the nuptial yearning of Earth, who is impregnated by the rain from above” which is the metaphorical synthesis of the oneiric ethereality of the heavens and the collectivity of thought, synthesized with the externality of the Earth and manifested as individual action.9

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

But I believe that the Industrial Revolution, including developments leading to this Revolution, barely capture what was unique about Western culture. I am obviously aware that other cultures were unique in having their own customs, languages, beliefs and historical experiences. My claim is that the West was uniquely exceptional in exhibiting in a continuous way the greatest degree of creativity, novelties, and expansionary dynamic. I trace the uniqueness of the West back to the aristocratic warlike culture of

But I believe that the Industrial Revolution, including developments leading to this Revolution, barely capture what was unique about Western culture. I am obviously aware that other cultures were unique in having their own customs, languages, beliefs and historical experiences. My claim is that the West was uniquely exceptional in exhibiting in a continuous way the greatest degree of creativity, novelties, and expansionary dynamic. I trace the uniqueness of the West back to the aristocratic warlike culture of

What was the ultimate original ground of the West’s Faustian soul? There are statements in Spengler which make references to “a Nordic world stretching from England to Japan” and a “harder-struggling” people, and a more individualistic and heroic spirit “in the old, genuine parts of the Mahabharata . . . in Homer, Pindar, and Aeschylus, in the Germanic epic poetry and in Shakespeare, in many songs of the Chinese Shuking, and in circles of the Japanese samurai” (as cited in Farrenkopf: 227). Spengler makes reference to the common location of these peoples in the “Nordic” steppes. He does not make any specific reference to the Caucasian steppes but he clearly has in mind the “Aryan Indian” peoples who came out of the steppes and conquered India and wrote the Mahabharata. He calls “half Nordic” the Graeco-Roman, Aryan Indian, and Chinese high cultures. In Man and Technics, he writes of how the Nordic climate forged a man filled with vitality

What was the ultimate original ground of the West’s Faustian soul? There are statements in Spengler which make references to “a Nordic world stretching from England to Japan” and a “harder-struggling” people, and a more individualistic and heroic spirit “in the old, genuine parts of the Mahabharata . . . in Homer, Pindar, and Aeschylus, in the Germanic epic poetry and in Shakespeare, in many songs of the Chinese Shuking, and in circles of the Japanese samurai” (as cited in Farrenkopf: 227). Spengler makes reference to the common location of these peoples in the “Nordic” steppes. He does not make any specific reference to the Caucasian steppes but he clearly has in mind the “Aryan Indian” peoples who came out of the steppes and conquered India and wrote the Mahabharata. He calls “half Nordic” the Graeco-Roman, Aryan Indian, and Chinese high cultures. In Man and Technics, he writes of how the Nordic climate forged a man filled with vitality There can no development of the human faculties, no high culture, without conflict, aggression, and pride. It is these asocial traits, “vainglory,” “lust for power,” “avarice,” which awaken the otherwise dormant talents of humans and “drive them to new exertions of their forces and thus to the manifold development of their capacities.” Nature in her wisdom, “not the hand of an evil spirit,” created “the unsocial sociability of humans.”

There can no development of the human faculties, no high culture, without conflict, aggression, and pride. It is these asocial traits, “vainglory,” “lust for power,” “avarice,” which awaken the otherwise dormant talents of humans and “drive them to new exertions of their forces and thus to the manifold development of their capacities.” Nature in her wisdom, “not the hand of an evil spirit,” created “the unsocial sociability of humans.” But how do we connect the barbaric asocial traits of prehistoric Indo-European warriors to the superlative cultural achievements of Greeks and later civilized Europeans? Nietzsche provides us some keen insights as to how the untamed agonistic ethos of Indo-Europeans was translated into civilized creativity. In his fascinating early essay, “Homer on Competition” (1872), Nietzsche observes that civilized culture or convention (nomos) was not imposed on nature but was a sublimated continuation of the strife that was already inherent to nature (physis). The nature of existence is based on conflict and this conflict unfolded itself in human institutions and governments. Humans are not naturally harmonious and rational as Socrates had insisted; the nature of humanity is strife. Without strife there is no cultural development. Nietzsche argued against the separation of man/culture from nature: the cultural creations of humanity are expressions or aspects of nature itself.

But how do we connect the barbaric asocial traits of prehistoric Indo-European warriors to the superlative cultural achievements of Greeks and later civilized Europeans? Nietzsche provides us some keen insights as to how the untamed agonistic ethos of Indo-Europeans was translated into civilized creativity. In his fascinating early essay, “Homer on Competition” (1872), Nietzsche observes that civilized culture or convention (nomos) was not imposed on nature but was a sublimated continuation of the strife that was already inherent to nature (physis). The nature of existence is based on conflict and this conflict unfolded itself in human institutions and governments. Humans are not naturally harmonious and rational as Socrates had insisted; the nature of humanity is strife. Without strife there is no cultural development. Nietzsche argued against the separation of man/culture from nature: the cultural creations of humanity are expressions or aspects of nature itself. This agonistic ethos was ingrained in the Olympic Games, in the perpetual warring of the city-states, in the pursuit of a political career and in the competition among orators for the admiration of the citizens, and in the Athenian theater festivals where a great many poets would take part in Dionysian competitions. It was evident in the sophistic-Socratic ethos of dialogic argument and the pursuit of knowledge by comparing and criticizing individual speeches, evaluating contradictory claims, collecting out evidence, competitive persuasion and refutation. And in the Catholic scholastic method, according to which critics would engage major works, read them thoroughly, compare the book’s theories to other authorities, and through a series of dialogical exercises ascertain the respective merits and demerits.

This agonistic ethos was ingrained in the Olympic Games, in the perpetual warring of the city-states, in the pursuit of a political career and in the competition among orators for the admiration of the citizens, and in the Athenian theater festivals where a great many poets would take part in Dionysian competitions. It was evident in the sophistic-Socratic ethos of dialogic argument and the pursuit of knowledge by comparing and criticizing individual speeches, evaluating contradictory claims, collecting out evidence, competitive persuasion and refutation. And in the Catholic scholastic method, according to which critics would engage major works, read them thoroughly, compare the book’s theories to other authorities, and through a series of dialogical exercises ascertain the respective merits and demerits.

The unique characteristics of Faustian civilization, as Spengler described it, are now leading Europe to destruction. The Faustian is characterized by a drive towards the infinite, a will to break through the boundaries that limit man, whether they be intellectual or physical. Spengler calls the prime symbol of the Faustian soul “limitless space.”[1] Like Goethe’s Faust, Faustian civilization seeks infinite knowledge.

The unique characteristics of Faustian civilization, as Spengler described it, are now leading Europe to destruction. The Faustian is characterized by a drive towards the infinite, a will to break through the boundaries that limit man, whether they be intellectual or physical. Spengler calls the prime symbol of the Faustian soul “limitless space.”[1] Like Goethe’s Faust, Faustian civilization seeks infinite knowledge.

Related to the Faustian tendency towards abstraction is the technical sophistication of Faustian civilization. Inventions spring from the unbounded Faustian mind. From the tools of abstract mathematics Faustian man has constructed the most precise and powerful theories of physical forces known to man. The combination of unlimited thought and dynamism enabled never before seen technological breakthroughs.

Related to the Faustian tendency towards abstraction is the technical sophistication of Faustian civilization. Inventions spring from the unbounded Faustian mind. From the tools of abstract mathematics Faustian man has constructed the most precise and powerful theories of physical forces known to man. The combination of unlimited thought and dynamism enabled never before seen technological breakthroughs.

Robert STEUCKERS (1987):

Postmodern Challenges:

Between Faust & Narcissus, Part 1

In Oswald Spengler’s terms, our European culture is the product of a “pseudomorphosis,” i.e., of the grafting of an alien mentality upon our indigenous, original, and innate mentality. Spengler calls the innate mentality “the Faustian.”

The Confrontation of the Innate and the Acquired

The alien mentality is the theocentric, “magical” outlook born in the Near East. For the magical mind, the ego bows respectfully before the divine substance like a slave before his master. Within the framework of this religiosity, the individual lets himself be guided by the divine force that he absorbs through baptism or initiation.

There is nothing comparable for the old-European Faustian spirit, says Spengler. Homo europeanus, in spite of the magic/Christian varnish covering our thinking, has a voluntarist and anthropocentric religiosity. For us, the good is not to allow oneself to be guided passively by God, but rather to affirm and carry out our own will. “To be able to choose,” this is the ultimate basis of the indigenous European religiosity. In medieval Christianity, this voluntarist religiosity shows through, piercing the crust of the imported “magism” of the Middle East.

Around the year 1000, this dynamic voluntarism appears gradually in art and literary epics, coupled with a sense of infinite space within which the Faustian self would, and can, expand. Thus to the concept of a closed space, in which the self finds itself locked, is opposed the concept of an infinite space, into which an adventurous self sallies forth.

From the “Closed” World to the Infinite Universe

According to the American philosopher Benjamin Nelson,[1] the old Hellenic sense of physis (nature), with all the dynamism this implies, triumphed at the end of the 13th century, thanks to Averroism, which transmitted the empirical wisdom of the Greeks (and of Aristotle in particular) to the West. Gradually, Europe passed from the “closed world” to the infinite universe. Empiricism and nominalism supplanted a Scholasticism that had been entirely discursive, self-referential, and self-enclosed. The Renaissance, following Copernicus and Bruno (the tragic martyr of Campo dei Fiori), renounced geocentrism, making it safe to proclaim that the universe is infinite, an essentially Faustian intuition according to Spengler’s criteria.

In the second volume of his History of Western Thought, Jean-François Revel, who formerly officiated at Point and unfortunately illustrated the Americanocentric occidentalist ideology, writes quite pertinently: “It is easy to understand that the eternity and infinity of the universe announced by Bruno could have had, on the cultivated men of the time, the traumatizing effect of passing from life in the womb into the vast and cruel draft of an icy and unbounded vortex.”[2]

The “magic” fear, the anguish caused by the collapse of the comforting certitude of geocentrism, caused the cruel death of Bruno, that would become, all told, a terrifying apotheosis . . . Nothing could ever refute heliocentrism, or the theory of the infinitude of sidereal spaces. Pascal would say, in resignation, with the accent of regret: “The eternal silence of these infinite spaces frightens me.”

From Theocratic Logos to Fixed Reason

To replace magical thought’s “theocratic logos,” the growing and triumphant bourgeois thought would elaborate a thought centered on reason, an abstract reason before which it is necessary to bow, like the Near Easterner bows before his god. The “bourgeois” student of this “petty little reason,” virtuous and calculating, anxious to suppress the impulses of his soul or his spirit, thus finds a comfortable finitude, a closed off and secured space. The rationalism of this virtuous human type is not the adventurous, audacious, ascetic, and creative rationalism described by Max Weber[3] which educates the inner man precisely to face the infinitude affirmed by Giordano Bruno.[4]

From the end of the Renaissance, Two Modernities are Juxtaposed

The petty rationalism denounced by Sombart[5] dominates the cities by rigidifying political thought, by restricting constructive activist impulses. The genuinely Faustian and conquering rationalism described by Max Weber would propel European humanity outside its initial territorial limits, giving the main impulse to all sciences of the concrete.

From the end of the Renaissance, we thus discover, on the one hand, a rigid and moralistic modernity, without vitality, and, on the other hand, an adventurous, conquering, creative modernity, just as we are today on the threshold of a soft post-modernity or of a vibrant post-modernity, self-assured and potentially innovative. By recognizing the ambiguity of the terms “rationalism,” “rationality,” “modernity,” and “post-modernity,” we enter one level of the domain of political ideologies, even militant Weltanschauungen.

The rationalization glutted with moral arrogance described by Sombart in his famous portrait of the “bourgeois” generates the soft and sentimental messianisms, the great tranquillizing narratives of contemporary ideologies. The conquering rationalization described by Max Weber causes the great scientific discoveries and the methodical spirit, the ingenious refinement of the conduct of life and increasing mastery of the external world.

This conquering rationalization also has its dark side: It disenchants the world, drains it, excessively schematizes it. While specializing in one or another domain of technology, science, or the spirit, while being totally invested there, the “Faustians” of Europe and North America often lead to a leveling of values, a relativism that tends to mediocrity because it makes us lose the feeling of the sublime, of the telluric mystique, and increasingly isolates individuals. In our century, the rationality lauded by Weber, if positive at the beginning, collapsed into quantitativist and mechanized Americanism that instinctively led by way of compensation, to the spiritual supplement of religious charlatanism combining the most delirious proselytism and sniveling religiosity.

Such is the fate of “Faustianism” when severed from its mythic foundations, of its memory of the most ancient, of its deepest and most fertile soil. This caesura is unquestionably the result of pseudomorphosis, the “magian” graft on the Faustian/European trunk, a graft that failed. “Magianism” could not immobilize the perpetual Faustian drive; it has—and this is more dangerous—cut it off from its myths and memory, condemned it to sterility and dessication, as noted by Valéry, Rilke, Duhamel, Céline, Drieu, Morand, Maurois, Heidegger, or Abellio.

Conquering Rationality, Moralizing Rationality, the Dialectic of Enlightenment, the “Grand Narratives” of Lyotard

Conquering rationality, if it is torn away from its founding myths, from its ethno-identitarian ground, its Indo-European matrix, falls—even after assaults that are impetuous, inert, emptied of substance—into the snares of calculating petty rationalism and into the callow ideology of the “Grand Narratives” of rationalism and the end of ideology. For Jean-François Lyotard, “modernity” in Europe is essentially the “Grand Narrative” of the Enlightenment, in which the heroes of knowledge work peacefully and morally toward an ethico-political happy ending: universal peace, where no antagonism will remain.[6] The “modernity” of Lyotard corresponds to the famous “Dialectic of the Enlightenment” of Horkheimer and Adorno, leaders of famous “Frankfurt School.”[7] In their optic, the work of the man of science or the action of the politician, must be submitted to a rational reason, an ethical corpus, a fixed and immutable moral authority, to a catechism that slows down their drive, that limits their Faustian ardor. For Lyotard, the end of modernity, thus the advent of “post-modernity,” is incredulity—progressive, cunning, fatalistic, ironic, mocking—with regard to this metanarrative.

Incredulity also means a possible return of the Dionysian, the irrational, the carnal, the turbid, and disconcerting areas of the human soul revealed by Bataille or Caillois, as envisaged and hoped by professor Maffesoli,[8] of the University of Strasbourg, and the German Bergfleth,[9] a young nonconformist philosopher; that is to say, it is equally possible that we will see a return of the Faustian spirit, a spirit comparable with that which bequeathed us the blazing Gothic, of a conquering rationality which has reconnected with its old European dynamic mythology, as Guillaume Faye explains in Europe and Modernity.[10]

Notes

1. Benjamin Nelson, Der Ursprung der Moderne, Vergleichende Studien zum Zivilisationsprozess [The Origin of Modernity: Comparative Studies of the Civilization Process] (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1986).

2. Jean-François Revel, Histoire de la pensée occidentale [History of Western Thought], vol. 2, La philosophie pendant la science (XVe, XVIe et XVIIe siècles) [Philosophy and Science (Fifteenth-, Sixteenth-, and Seventeenth-Centuries)] (Paris: Stock, 1970). Cf. also the masterwork of Alexandre Koyré, From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1957).

3. Cf. Julien Freund, Max Weber (Paris: P.U.F., 1969).

4. Paul-Henri Michel, La cosmologie de Giordano Bruno [The Cosmology of Giordano Bruno] (Paris: Hermann, 1962).

5. Cf. essentially: Werner Sombart, Le Bourgeois. Contribution à l’histoire morale et intellectuelle de l’homme économique moderne [The Bourgeois: Contribution to the Moral and Intellectual History of Modern Economic Man] (Paris: Payot, 1966).

6. Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, trans. Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984).

7. Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adomo, The Dialectic of Enlightenment, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002). Cf. also Pierre Zima, L’École de Francfort. Dialectique de la particularité [The Frankfurt School: Dialectic of Particularity] (Paris: Éditions Universitaires, 1974). Michel Crozon, “Interroger Horkheimer” [“Interrogating Horkheimer”] and Arno Victor Nielsen, “Adorno, le travail artistique de la raison” [“Adorno: The Artistic Work of Reason”], Esprit, May 1978.

8. Cf. chiefly Michel Maffesoli, L’ombre de Dionysos: Contribution à une sociologie de l’orgie [The Shadow of Dionysus: Contribution to a Sociology of the Orgy] (Méridiens, 1982). Pierre Brader, “Michel Maffesoli: saluons le grand retour de Dionysos” [Michel Maffesoli: Let us Greet the Great return of Dionysos], Magazine-Hebdo no. 54 (September 21, 1984).

9. Cf. Gerd Bergfleth et al., Zur Kritik der Palavernden Aufklärung [Toward a Critique of Palavering Reason] (Munich: Matthes & Seitz, 1984). In this remarkable little anthology, Bergfleth published four texts deadly to the “moderno-Frankfurtist” routine: (1) “Zehn Thesen zur Vernunftkritik” [“Ten Theses on the Critique of Reason”]; (2) “Der geschundene Marsyas” [“The Abuse of Marsyas”]; (3) “Über linke Ironie” [“On Leftist Irony”]; (4) “Die zynische Aufklärung” [“The Cynical Enlightnement”]. Cf. also R. Steuckers, “G. Bergfleth: enfant terrible de la scène philosophique allemande” [“G. Bergfleth: enfant terrible of the German philosophical scene”], Vouloir no. 27 (March 1986). In the same issue, see also M. Kamp, “Bergfleth: critique de la raison palabrante” [“Bergfleth: Critique of Palavering Reason”] and “Une apologie de la révolte contre les programmes insipides de la révolution conformiste” [“An Apology for the Revolt against the Insipid Programs of the Conformist Revolution”]. See also M. Froissard, “Révolte, irrationnel, cosmicité et . . . pseudo-antisémitisme,” [“Revolt, irrationality, cosmicity and . . . pseudo-anti-semitism”], Vouloir nos. 40–42 (July–August 1987).

10. Guillaume Faye, Europe et Modernité [Europe and Modernity] (Méry/Liège: Eurograf, 1985).

Postmodern Challenges:

Between Faust & Narcissus, Part 2

Once the Enlightenment metanarrative was established—“encysted”—in the Western mind, the great secular ideologies progressively appeared: liberalism, with its idolatry of the “invisible hand,”[1] and Marxism, with its strong determinism and metaphysics of history, contested at the dawn of the 20th century by Georges Sorel, the most sublime figure of European militant socialism.[2] Following Giorgio Locchi[3]—who occasionally calls the metanarrative “ideology” or “science”—we think that this complex “metanarrative/ideology/science” no longer rules by consensus but by constraint, inasmuch as there is muted resistance (especially in art and music[4]) or a general disuse of the metanarrative as one of the tools of legitimation.

The liberal-Enlightenment metanarrative persists by dint of force and propaganda. But in the sphere of thought, poetry, music, art, or letters, this metanarrative says and inspires nothing. It has not moved a great mind for 100 or 150 years. Already at the end of the 19th century, literary modernism expressed a diversity of languages, a heterogeneity of elements, a kind of disordered chaos that the “physiologist” Nietzsche analyzed[5] and that Hugo von Hoffmannstahl called die Welt der Bezuge (the world of relations).

These omnipresent interrelations and overdeterminations show us that the world is not explained by a simple, neat and tidy story, nor does it submit itself to the rule of a disincarnated moral authority. Better: they show us that our cities, our people, cannot express all their vital potentialities within the framework of an ideology given and instituted once and for all for everyone, nor can we indefinitely preserve the resulting institutions (the doctrinal body derived from the “metanarrative of the Enlightenment”).

The anachronistic presence of the metanarrative constitutes a brake on the development of our continent in all fields: science (data-processing and biotechnology[6]), economics (the support of liberal dogmas within the EEC), military (the fetishism of a bipolar world and servility toward the United States, paradoxically an economic enemy), cultural (media bludgeoning in favor of a cosmopolitanism that eliminates Faustian specificity and aims at the advent of a large convivial global village, run on the principles of the “cold society” in the manner of the Bororos dear to Lévi-Strauss[7]).

The Rejection of Neo-Ruralism, Neo-Pastoralism . . .

The confused disorder of literary modernism at the end of the 19th century had a positive aspect: its role was to be the magma that, gradually, becomes the creator of a new Faustian assault.[8] It is Weimar—specifically, the Weimar-arena of the creative and fertile confrontation of expressionism,[9] neo-Marxism, and the “conservative revolution”[10]—that bequeathed us, with Ernst Jünger, an idea of “post-metanarrative” modernity (or post-modernity, if one calls “modernity” the Dialectic of the Enlightenment, subsequently theorized by the Frankfurt School). Modernism, with the confusion it inaugurates, due to the progressive abandonment the pseudo-science of the Enlightenment, corresponds somewhat to the nihilism observed by Nietzsche. Nihilism must be surmounted, exceeded, but not by a sentimental return, however denied, to a completed past. Nihilism is not surpassed by theatrical Wagnerism, Nietzsche fulminated, just as today the foundering of the Marxist “Grand Narrative” is not surpassed by a pseudo-rustic neoprimitivism.[11]

In Jünger—the Jünger of In Storms of Steel, The Worker, and Eumeswil—one finds no reference to the mysticism of the soil: only a sober admiration for the perennialness of the peasant, indifferent to historical upheavals. Jünger tells us of the need for balance: if there is a total refusal of the rural, of the soil, of the stabilizing dimension of Heimat, constructivist Faustian futurism will no longer have a base, a point of departure, a fallback option. On the other hand, if the accent is placed too much on the initial base, the launching point, on the ecological niche that gives rise to the Faustian people, then they are wrapped in a cocoon and deprived of universal influence, rendered blind to the call of the world, prevented from springing towards reality in all its plenitude, the “exotic” included. The timid return to the homeland robs Faustianism of its force of diffusion and relegates its “human vessels” to the level of the “eternal ahistoric peasants” described by Spengler and Eliade.[12] Balance consists in drawing in (from the depths of the original soil) and diffusing out (towards the outside world).

In spite of all nostalgia for the “organic,” rural, or pastoral—in spite of the serene, idyllic, aesthetic beauty that recommend Horace or Virgil—Technology and Work are from now on the essences of our post-nihilist world. Nothing escapes any longer from technology, technicality, mechanics, or the machine: neither the peasant who plows with his tractor nor the priest who plugs in a microphone to give more impact to his homily.

The era of “Technology”

Technology mobilizes totally (Total Mobilmachung) and thrusts the individual into an unsettling infinitude where we are nothing more than interchangeable cogs. The machine gun, notes the warrior Jünger, mows down the brave and the cowardly with perfect equality, as in the total material war inaugurated in 1917 in the tank battles of the French front. The Faustian “Ego” loses its intraversion and drowns in a ceaseless vortex of activity. This Ego, having fashioned the stone lacework and spires of the flamboyant Gothic, has fallen into American quantitativism or, confused and hesitant, has embraced the 20th century’s flood of information, its avalanche of concrete facts. It was our nihilism, our frozen indecision due to an exacerbated subjectivism, that mired us in the messy mud of facts.

By crossing the “line,” as Heidegger and Jünger say,[13] the Faustian monad (about which Leibniz[14] spoke) cancels its subjectivism and finds pure power, pure dynamism, in the universe of Technology. With the Jüngerian approach, the circle is closed again: as the closed universe of “magism” was replaced by the inauthentic little world of the bourgeois—sedentary, timid, embalmed in his utilitarian sphere—so the dynamic “Faustian” universe is replaced with a Technological arena, stripped this time of all subjectivism.

Jüngerian Technology sweeps away the false modernity of the Enlightenment metanarrative, the hesitation of late 19th century literary modernism, and the trompe-l’oeil of Wagnerism and neo-pastoralism. But this Jüngerian modernity, perpetually misunderstood since the publication of Der Arbeiter [The Worker] in 1932, remains a dead letter.

Notes

1. On the theological foundation of the doctrine of the “invisible hand” see Hans Albert, “Modell-Platonismus. Der neoklassische Stil des ökonomischen Denkens in kritischer Beleuchtung” [“Model Platonism: The Neoclassical Style of Economic Thought in Critical Elucidation”], in Ernst Topitsch, ed., Logik der Sozialwissenschaften [Logic of Social Science] (Köln/Berlin: Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 1971).

2. There is abundant French literature on Georges Sorel. Nevertheless, it is deplorable that a biography and analysis as valuable as Michael Freund’s has not been translated: Michael Freund, Georges Sorel, Der revolutionäre Konservatismus [Georges Sorel: Revolutionary Conservatism] (Frankfurt a.M.: Vittorio Klostermann, 1972).

3. Cf. G. Locchi, “Histoire et société: critique de Lévi-Strauss” [“History and Society: Critique of Lévi-Strauss”], Nouvelle Ecole, no. 17 (March 1972) and “L’histoire” [“History”], Nouvelle Ecole, nos. 27–28 (January 1976).

4. Cf. G. Locchi, “L’idée de la musique’ et le temps de l’histoire” [“The ‘Idea of Music’ and the Times of History”], Nouvelle Ecole, no. 30 (November 1978) and Vincent Samson, “Musique, métaphysique et destin” [“Music, Metaphysics, and Destiny”], Orientations, no. 9 (September 1987).

5. Cf. Helmut Pfotenhauer, Die Kunst als Physiologie: Nietzsches äesthetische Theorie und literarische Produktion [Art as Physiology: Nietzsche’s Aesthetic Theory and Literary Production] (Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler, 1985). Cf. on Pfotenhauer’s book: Robert Steuckers, “Regards nouveaux sur Nietzsche” [“New Views of Nietzsche”], Orientations, no. 9.