Myth: The US was forced to declare war on Japan after a totally unexpected Japanese attack on the American naval base in Hawaii on December 7, 1941. On account of Japan’s alliance with Nazi Germany, this aggression automatically brought the US into the war against Germany.

Reality: The Roosevelt administration had been eager for some time to wage war against Japan and sought to unleash such a war by means of the institution of an oil embargo and other provocations. Having deciphered Japanese codes, Washington knew a Japanese fleet was on its way to Pearl Harbor, but welcomed the attack since a Japanese aggression would make it possible to “sell” the war to the overwhelmingly anti-war American public.

An attack by Japan, as opposed to an American attack on Japan, was also supposed to avoid a declaration of war by Japan’s ally, Germany, which was treaty-bound to help only if Japan was attacked. However, for reasons which have nothing to do with Japan or the US but everything with the failure of Germany’s “lightning war” against the Soviet Union, Hitler himself declared war on the US a few days after Pearl Harbor, on December 11, 1941.

Fall 1941. The US, then as now, was ruled by a “Power Elite” of industrialists, owners and managers of the country’s leading corporations and banks, constituting only a tiny fraction of its population. Then as now, these industrialists and financiers – “Corporate America” – had close connections with the highest ranks of the army, “the warlords,” as Columbia University sociologist C. Wright Mills, who coined the term “power elite,”[1] has called them, and for whom a few years later a big HQ, known as the Pentagon, would be erected on the banks of the Potomac River.

Indeed, the “military-industrial complex” had already existed for many decades when, at the end of his career as President, and having served it most assiduously, Eisenhower gave it that name. Talking about presidents: in the 1930s and 1940s, again then as now, the Power Elite kindly allowed the American people every four years to choose between two of the elite’s own members – one labelled “Republican,” the other “Democrat,” but few people know the difference – to reside in the White House in order to formulate and administer national and international policies. These policies invariably served – and still serve – the Power Elite’s interests, in other words, they consistently aimed to promote “business” – a code word for the maximization of profits by the big corporations and banks that are members of the Power Elite.

As President Calvin Coolidge candidly put it on one occasion during the 1920s, “the business of America [meaning of the American government] is business.” In 1941, then, the tenant of the White House was a bona fide member of the Power Elite, a scion of a rich, privileged, and powerful family: Franklin D. Roosevelt, often referred to as “FDR”. (Incidentally, the Roosevelt family’s wealth had been built at least partly in the opium trade with China; as Balzac once wrote, “behind every great fortune there lurks a crime.”)

Roosevelt appears to have served the Power Elite rather well, for he already managed to be nominated (difficult!) and elected (relatively easy!) in 1932, 1936, and again in 1940. That was a remarkable achievement, since the “dirty thirties” were hard times, marked by the “Great Depression” as well as great international tensions, leading to the eruption of war in Europe in 1939. Roosevelt’s job – serving the interests of the Power Elite – was far from easy, because within the ranks of that elite opinions differed about how corporate interests could best be served by the President. With respect to the economic crisis, some industrialists and bankers were pretty happy with the President’s Keynesian approach, known as the “New Deal” and involving much state intervention in the economy, while others were vehemently opposed to it and loudly demanded a return to laissez-faire orthodoxy. The Power Elite was also divided with respect to the handling of foreign affairs.

The owners and top managers of many American corporations – including Ford, General Motors, IBM, ITT, and Rockefeller’s Standard Oil of New Jersey, now known as Exxon – liked Hitler a lot; one of them – William Knudsen of General Motors – even glorified the German Führer as “the miracle of the 20th century.”[2] The reason: in preparation for war, the Führer had been arming Germany to the teeth, and the numerous German branch plants of US corporations had profited handsomely from that country’s “armament boom” by producing trucks, tanks and planes in sites such as GM’s Opel factory in Rüsselsheim and Ford’s big plant in Cologne, the Ford-Werke; and the likes of Exxon and Texaco had been making plenty of money by supplying the fuel Hitler’s panzers would need to roll all the way to Warsaw in 1939, to Paris in 1940, and (almost) to Moscow in 1941. No wonder the managers and owners of these corporations helped to celebrate Germany’s victories against Poland and France at a big party in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York on June 26, 1940!

American “captains of industry” like Henry Ford also liked the way Hitler had shut down the German unions, outlawed all labour parties, and thrown the communists and many socialists into concentration camps; they wished Roosevelt would mete out the same kind of treatment to America’s own pesky union leaders and “reds,” the latter still numerous in the 1930s and early 1940s. The last thing those men wanted, was for Roosevelt to involve the US in the war on the side of Germany’s enemies, they were “isolationists” (or “non-interventionists”) and so, in the summer of 1940, was the majority of the American public: a Gallup Poll, taken in September 1940, showed that 88 percent of Americans wanted to stay out of the war that was raging in Europe.[3] Not surprisingly, then, there was no sign whatsoever that Roosevelt might want to restrict trade with Germany, let alone embark on an anti-Hitler crusade. In fact, during the presidential election campaign in the fall 1940, he solemnly promised that “[our] boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.”[4]

That Hitler has crushed France and other democratic countries, was of no concern to the US corporate types who did business with Hitler, in fact, they felt that Europe’s future belonged to fascism, especially Germany’s variety of fascism, Nazism, rather than to democracy. (Typically, the chairman of General Motors, Alfred P. Sloan, declared at that time that it was a good thing that in Europe the democracies were giving way “to an alternative [i.e. fascist] system with strong, intelligent, and aggressive leaders who made the people work longer and harder and who had the instinct of gangsters – all of them good qualities”!)[5] And, since they certainly did not want Europe’s future to belong to socialism in its evolutionary, let alone revolutionary (i.e. communist) variety, the US industrialists would be particularly happy when, about one year later, Hitler would finally do what they have long hoped he would do, namely, to attack the Soviet Union in order to destroy the homeland of communism and source of inspiration and support of “reds” all over the world, also in the US.

While many big corporations were engaged in profitable business with Nazi Germany, others now happened to be making plenty of money by doing business with Great Britain. That country – in addition to Canada and other member countries of the British Empire, of course – was Germany’s only remaining enemy from the fall of 1940 until June 1941, when Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union caused Britain and the Soviet Union to become allies. Britain was desperately in need of all sorts of equipment to continue its struggle against Nazi Germany, wanted to purchase much of it in the US, but was unable to make the cash payments required by America’s existing “Cash-and-Carry” legislation. However, Roosevelt made it possible for US corporations to take advantage of this enormous “window of opportunity” when, on March 11, 1941, he introduced his famous Lend-Lease program, providing Britain with virtually unlimited credit to purchase trucks, planes, and other martial hardware in the US. The Lend-Lease exports to Britain were to generate windfall profits, not only on account of the huge volume of business involved but also because these exports featured inflated prices and fraudulent practices such as double billing.

A segment of Corporate America thus began to sympathize with Great Britain, a less “natural” phenomenon than we would now tend to believe. (Indeed, after American independence the ex-motherland had long remained Uncle Sam’s archenemy; and as late the 1930s, the US military still had plans for war against Britain and an invasion of the Canadian Dominion, the latter including plans for the bombing of cities and the use of poison gas.)[6] Some mouthpieces of this corporate constituency, though not very many, even started to favour a US entry into the war on the side of the British; they became known as the “interventionists.” Of course, many if not most big American corporations made money through business with both Nazi Germany and Britain and, as the Roosevelt administration itself was henceforth preparing for possible war, multiplying military expenditures and ordering all sorts of equipment, they also started to make more and more money by supplying America’s own armed forces with all sorts of martial material.[7]

If there was one thing that all the leaders of Corporate America could agree on, regardless of their individual sympathies towards either Hitler or Churchill, it was this: the war in Europe in 1939 was good, even wonderful, for business. They also agreed that the longer this war lasted, the better it would be for all of them. With the exception of the most fervent pro-British interventionists, they further agreed that there was no pressing need for the US to become actively involved in this war, and certainly not to go to war against Germany. Most advantageous to Corporate America was a scenario whereby the war in Europe dragged on as long as possible, so that the big corporations could continue to profit from supplying equipment to the Germans, the British, to their respective allies, and to America herself. Henry Ford thus “expressed the hope that neither the Allies nor the Axis would win [the war],” and suggested that the United States should supply both sides with “the tools to keep on fighting until they both collapse.” Ford practised what he preached, and arranged for his factories in the US, in Britain, in Germany, and in occupied France to crank out equipment for all belligerents.[8] The war may have been hell for most people, but for American “captains of industry” such as Ford it was heaven.

Roosevelt himself is generally believed to have been an interventionist, but in Congress the isolationists certainly prevailed, and it did not look as if the US would soon, if ever, enter the war. However, on account of Lend-Lease exports to Britain, relations between Washington and Berlin were definitely deteriorating, and in the fall of 1941 a series of incidents between German submarines and US Navy destroyers escorting freighters bound for Britain lead to a crisis that has become known as the “undeclared naval war.” But even that episode did not lead to active American involvement in the war in Europe. Corporate America was profiting handsomely from the status quo, and was simply not interested in a crusade against Nazi Germany. Conversely, Nazi Germany was deeply involved in the great project of Hitler’s life, his mission to destroy the Soviet Union. In this war, things had not been going according to plan. The Blitzkrieg in the East, launched on June 1941, was supposed to have “crushed the Soviet Union like an egg” within 4 to 6 weeks, or so it was believed by the military experts not only in Berlin but also in Washington. However, in early December Hitler was still waiting for the Soviets to wave the white flag. To the contrary, on December 5, the Red Army suddenly launched a counter-offensive in front of Moscow, and suddenly the Germans found themselves deeply in trouble. The last thing Hitler needed at this point was a war against the US.[9]

In the 1930s, the US military had no plans, and did not prepare plans, to fight a war against Nazi Germany. On the other hand, they did have plans war against Great Britain, Canada, Mexico – and Japan.[10] Why against Japan? In the 1930s, the US was one of the world’s leading industrial powers and, like all industrial powers, was constantly looking out for sources of inexpensive raw materials such as rubber and oil, as well as for markets for its finished products. Already at the end of the nineteenth century, America had consistently pursued its interests in this respect by extending its economic and sometimes even direct political influence across oceans and continents. This aggressive, “imperialist” policy – pursued ruthlessly by presidents such as Theodore Roosevelt, a cousin of FDR – had led to American control over former Spanish colonies such as Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Philippines, and also over the hitherto independent island nation of Hawaii. America had thus also developed into a major power in the Pacific Ocean and even in the Far East.[11]

The lands on the far shores of the Pacific Ocean played an increasingly important role as markets for American export products and as sources of cheap raw materials. But in the Depression-ridden 1930s, when the competition for markets and resources was heating up, the US faced the competition there of an aggressive rival industrial power, one that was even more needy for oil and similar raw materials, and also for markets for its finished products. That competitor was Japan, the land of the rising sun. Japan sought to realize its own imperialist ambitions in China and in resource-rich Southeast Asia and, like the US, did not hesitate to use violence in the process, for example waging ruthless war on China and carving a client state out of the northern part of that great but weak country. What bothered the United States was not that the Japanese treated their Chinese and Korean neighbours as Untermenschen, but that they turned that part of the world into what they called the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, i.e., an economic bailiwick of their very own, a “closed economy” in with there was no room for the American competition. In doing so, the Japanese actually followed the example of the US, which had earlier transformed Latin America and much of the Caribbean into Uncle Sam’s exclusive economic playground.[12]

Corporate America was extremely frustrated at being squeezed out of the lucrative Far Eastern market by the “Japs,” a “yellow race” Americans in general had already started to despise during the 19th century.[13] Japan was viewed as an arrogant but essentially weak upstart country, that mighty America could easily “wipe off the map in three months,” as Navy Secretary Frank Knox put it on one occasion.[14] And so it happened that, during the 1930s and early 1940s, the US Power Elite, while mostly opposed to war against Germany, was virtually unanimously in favour of a war against Japan – unless, of course, Japan was prepared to make major concessions, such as “sharing” China with the US. President Roosevelt – like Woodrow Wilson not at all the pacifist he has been made out to be by all too many historians – was keen to provide such a “splendid little war.” (This expression had been coined by US Secretary of State John Hay in reference to the Spanish-American War of 1898; it was “splendid” in that it allowed the US to pocket the Philippines, Puerto Rico, etc.) By the summer of 1941, after Tokyo had further increased its zone of influence in the Far East, e.g. by occupying the rubber-rich French colony of Indochina and, desperate above all for oil, had obviously started to lust after the oil-rich Dutch colony of Indonesia, FDR appears to have decided that the time was ripe for war against Japan, but he faced two problems. First, public opinion was strongly against American involvement in any foreign war. Second, the isolationist majority in Congress might not consent to such a war, fearing that it would automatically bring the US into war against Germany.

Roosevelt’s solution to this twin problem, according to the author of a detailed and extremely well documented recent study, Robert B. Stinnett, was to “provoke Japan into an overt act of war against the United States.”[15] Indeed, in case of a Japanese attack the American public would have no choice but to rally behind the flag. (The public had similarly been made to rally behind the Stars and Stripes before, namely at the start of the Spanish-American War, when the visiting US battleship Maine had mysteriously sunk in Havana harbour, an act that was immediately blamed on the Spanish; after World War II, Americans would again be conditioned to approve of wars, wanted and planned by their government, by means of contrived provocations such as the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Incident.) Furthermore, under the terms of the Tripartite Treaty concluded by Japan, Germany, and Italy in Berlin on September 27, 1940, the three countries undertook to assist each other when one of the three contracting powers was attacked by another country, but not when one of them attacked another country. Consequently, in case of a Japanese attack on the US, the isolationists, who were non-interventionists with respect to Germany but not with respect to Japan, did not have to fear that a conflict with Japan would also mean war against Germany.

And so, President Roosevelt, having decided that “Japan must be seen to make the first overt move,” made “provoking Japan into an overt act of war the principal policy that guided [his] actions toward Japan throughout 1941,” as Stinnett has written. The stratagems used included the deployment of warships close to, and even into, Japanese territorial waters, apparently in the hope of sparking a Gulf of Tonkin-style incident that could be construed to be a casus belli. More effective, however, was the relentless economic pressure that was brought to bear on Japan, a country desperately in need of raw materials such as oil and rubber and therefore likely to consider such methods to be singularly provocative. In the summer of 1941, the Roosevelt administration froze all Japanese assets in the United States and embarked on a “strategy for frustrating Japanese acquisition of petroleum products.” In collaboration with the British and the Dutch, anti-Japanese for reasons of their own, the US imposed severe economic sanctions on Japan, including an embargo on vital oil products. The situation deteriorated further in the fall of 1941. On November 7, Tokyo, hoping to avoid war with the mighty US, offered to apply in China the principle of non-discriminatory trade relations on the condition that the Americans did the same in their own sphere of influence in Latin America. However, Washington wanted reciprocity only in the sphere of influence of other imperialist powers, and not in its own backyard; the Japanese offer was rejected.

The continuing US provocations of Japan were intended to cause Japan to go to war, and were indeed increasingly likely to do so. “This continuing putting pins in rattlesnakes,” FDR was to confide to friends later, “finally got this country bit.” On November 26, when Washington a demanded Japan’s withdrawal from China, the “rattlesnakes” in Tokyo decided they had enough and prepared to “bite.” A Japanese fleet was ordered to set sail for Hawaii in order to attack the US warships that FDR had decided to station there, rather provocatively as well as invitingly as far as the Japanese were concerned, in 1940. Having deciphered the Japanese codes, the American government and top army brass knew exactly what the Japanese armada was up to, but did not warn the commanders in Hawaii, thus allowing the “surprise attack” on Pearl Harbor to happen on Sunday, December 7, 1941.[16]

The following day FDR found it easy to convince Congress to declare war on Japan, and the American people, shocked by a seemingly cowardly attack that they could not know to have been provoked, and expected, by their own government, predictably rallied behind the flag. The US was ready to wage war against Japan, and the prospects for a relatively easy victory were hardly diminished by the losses suffered at Pearl Harbour which, while ostensibly grievous, were far from catastrophic. The ships that had been sunk were older, “mostly 27-year old relics of World War I,” and far from indispensible for warfare against Japan. The modern warships, on the other hand, including the aircraft carriers, whose role in the war would turn out to be crucial, were unscathed, as per chance (?) they had been sent elsewhere by orders from Washington and were safely out at sea during the attack.[17] However, things did not quite work out as expected, because a few days later, on December 11, Nazi Germany unexpectedly declared war, thus forcing the US to confront two enemies and to fight a much bigger war than expected, a war on two fronts, a world war.

In the White House, the news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor had not arrived as a surprise, but the German declaration of war exploded there as a bombshell. Germany had nothing to do with the attack in Hawaii and had not even been aware of the Japanese plans, so FDR did not consider asking Congress to declare war on Nazi Germany at the same time as Japan. Admittedly, US relations with Germany had been deteriorating for some time because of America’s active support for Great Britain, escalating to the undeclared naval war of the fall of 1941. However, as we have already seen, the US Power Elite did not feel the need to intervene in the war in Europe. It was Hitler himself who declared war on the United States on December 11, 1941, much to the surprise of Roosevelt. Why? Only a few days earlier, on December 5, 1941, the Red Army had launched a counteroffensive in front of Moscow, and this entailed the failure of the Blitzkrieg in the Soviet Union. On that same day, Hitler and his generals realized that they could no longer win the war. But when, only a few days later, the German dictator learned of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he appears to have speculated that a German declaration of war on the American enemy of his Japanese friends, though not required under the terms of the Tripartite Treaty, would induce Tokyo to reciprocate with a declaration of war on the Soviet enemy of Germany.

With the bulk of the Japanese army stationed in northern China and therefore able to immediately attack the Soviet Union in the Vladivostok area, a conflict with Japan would have forced the Soviets into the extremely perilous predicament of a two-front war, opening up the possibility that Germany might yet win its anti-Soviet “crusade.” Hitler, then, believed that he could exorcize the spectre of defeat by summoning a sort of Japanese deus ex machina to the Soviet Union’s vulnerable Siberian frontier. But Japan did not take Hitler’s bait. Tokyo, too, despised the Soviet state but, already at war against the US, could not afford the luxury of a two-front war and preferred to put all of its money on a “southern” strategy, hoping to win the big prize of resource-rich Southeast Asia, rather than embark on a venture in the inhospitable reaches of Siberia. Only at the very end of the war, after the surrender of Nazi Germany, would it come to hostilities between the Soviet Union and Japan. In any event, because of Hitler’s needless declaration of war, the United States was henceforth also an active participant in the war in Europe, with Great Britain and the Soviet Union as allies.[18]

In recent years, Uncle Sam has been going to war rather frequently, but we are invariably asked to believe that this is done for purely humanitarian reasons, i.e. to prevent holocausts, to stop terrorists from committing all sorts of evil, to get rid of nasty dictators, to promote democracy, etc.[19]

Never, it seems, are economic interests of the US or, more accurately, of America’s big corporations, involved. Quite often, these wars are compared to America’s archetypal “good war,” World War II, in which Uncle Sam supposedly went to war for no other reason than to defend freedom and democracy and to fight dictatorship and injustice. (In an attempt to justify his “war against terrorism,” for example, and “sell” it to the American public, George W. Bush was quick to compare the 9/11 attacks to Pearl Harbor.) This short examination of the circumstances of the US entry into the war in December 1941, however, reveals a very different picture. The American Power Elite wanted war against Japan, plans for such a war had been ready for some time, and in 1941 Roosevelt obligingly arranged for such a war, not because of Tokyo’s unprovoked aggression and horrible war crimes in China, but because American corporations wanted a share of the luscious big “pie” of Far Eastern resources and markets. On the other hand, because the major US corporations were doing wonderful business in and with Nazi Germany, profiting handsomely from the war Hitler had unleashed and, incidentally, providing him with the equipment and fuel required for his Blitzkrieg, war against Nazi Germany was definitely not wanted by the US Power Elite, even though there were plenty of compelling humanitarian reasons for crusading against the truly evil “Third Reich.” Prior to 1941, no plans for a war against Germany had been developed, and in December 1941 the US did not voluntarily go to war against Germany, but “backed into” that war because of Hitler’s own fault.

Humanitarian considerations played no role whatsoever in the calculus that led to America’s participation in World War II, the country’s original “good war.” And there is no reason to believe that they did so in the calculus that, more recently, led to America’s marching off to fight allegedly “good wars” in unhappy lands such as Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya – or will do so in the looming war against Iran.

A war against Iran is very much wanted by Corporate America, since it holds the promise of a large market and of plentiful raw materials, especially oil. As in the case of the war against Japan, plans for such a war are ready, and the present tenant in the White House seems just as eager as FDR was to make it happen. Furthermore, again as in the case of the war against Japan, provocations are being orchestrated, this time in the form of sabotage and intrusions by drones, as well as by the old-fashioned deployment of warships just outside Iranian territorial waters. Washington is again “putting pins in rattlesnakes,” apparently hoping that the Iranian “rattlesnake” will bite back, thus justifying a “splendid little war.” However, as in the case of Pearl Harbor, the resulting war may well again turn out to be much bigger, longer, and nastier than expected.

Jacques R. Pauwels is the author of The Myth of the Good War: America in the Second World War, James Lorimer, Toronto, 2002

Notes

[1] C. Wright Mills, The Power Elite, New York, 1956.

[2] Cited in Charles Higham, Trading with the Enemy: An Exposé of The Nazi-American Money Plot 1933-1949, New York, 1983, p. 163.

[3] Robert B. Stinnett, Day of Deceit: The Truth about FDR and Pearl Harbor, New York, 2001, p. 17.

[4] Cited in Sean Dennis Cashman, America, Roosevelt, and World War II, New York and London, 1989, p. 56; .

[5] Edwin Black, Nazi Nexus: America’s Corporate Connections to Hitler’s Holocaust, Washington/DC, 2009, p. 115.

[6] Floyd Rudmin, “Secret War Plans and the Malady of American Militarism,” Counterpunch, 13:1, February 17-19, 2006. pp. 4-6, http://www.counterpunch.org/2006/02/17/secret-war-plans-and-the-malady-of-american-militarism

[7] Jacques R. Pauwels, The Myth of the Good War : America in the Second World War, Toronto, 2002, pp. 50-56. The fraudulent practices of Lend-Lease are described in Kim Gold, “The mother of all frauds: How the United States swindled Britain as it faced Nazi Invasion,” Morning Star, April 10, 2003.

[8] Cited in David Lanier Lewis, The public image of Henry Ford: an American folk hero and his company, Detroit, 1976, pp. 222, 270.

[9] Jacques R. Pauwels, “70 Years Ago, December 1941: Turning Point of World War II,” Global Research, December 6, 2011, http://globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=va&aid=28059.

[10] Rudmin, op. cit.

[11] See e.g. Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, s.l., 1980, p. 305 ff.

[12] Patrick J. Hearden, Roosevelt confronts Hitler: America’s Entry into World War II, Dekalb/IL, 1987, p. 105.

[13] “Anti-Japanese sentiment,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-Japanese_sentiment

[14] Patrick J. Buchanan, “Did FDR Provoke Pearl Harbor?,” Global Research, December 7, 2011, http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=va&aid=28088 . Buchanan refers to a new book by George H. Nash, Freedom Betrayed: Herbert Hoover’s Secret History of the Second World War and its Aftermath, Stanford/CA, 2011.

[15] Stinnett, op. cit., p. 6.

[16] Stinnett, op. cit., pp. 5, 9-10, 17-19, 39-43; Buchanan, op. cit.; Pauwels, The Myth…, pp. 67-68. On American intercepts of coded Japanese messages, see Stinnett, op. cit., pp. 60-82. “Rattlesnakes”-quotation from Buchanan, op. cit.

[17] Stinnett, op. cit., pp. 152-154.

[18] Pauwels, “70 Years Ago…”

[19] See Jean Bricmont, Humanitarian imperialism: Using Human Rights to Sell War, New York, 2006.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

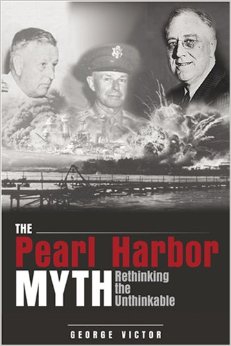

In this book, George Victor addresses the several questions regarding Pearl Harbor: did U.S. Intelligence know beforehand? Did Roosevelt know? If so, why weren’t commanders in Hawaii notified? It is a well-researched and documented volume, complete with hundreds of end-notes and references.

In this book, George Victor addresses the several questions regarding Pearl Harbor: did U.S. Intelligence know beforehand? Did Roosevelt know? If so, why weren’t commanders in Hawaii notified? It is a well-researched and documented volume, complete with hundreds of end-notes and references.