Author’s Note:

This is transcript by V. S. of a talk that I gave to the Atlanta Philosophical Society in 2000. As usual, I have eliminated some wordy constructions and some back-and-forth with the audience.

We live in a time when there’s a lot of talk about the ends of ages. Last year, at the end of 1999, the vast majority of people celebrating the New Year were celebrating the millennium a year early. But still, there’s a sense that when we reach a round number something important is going to happen. There’s a lot of talk about the “end of modernity” in academia today. So-called postmodernist philosophers and literary critics are quite popular, and certain religious thinkers and writers are of course concerned that time itself may end very soon.

A friend of mine who is an Orthodox monk in Bulgaria emailed me just before the New Year saying that not only did some people in Bulgaria think that all the computers were going to fail, they thought the end of time was at hand. I wrote back saying, “Well, if I don’t hear from you again, it’s been nice knowing you.”

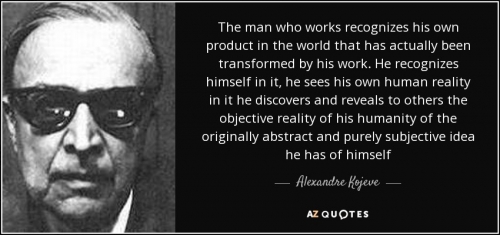

I want to talk about one of the most stunning claims that history is over, namely the claim popularized by Alexandre Kojève, a 20th-century philosopher who I think is probably the most influential single philosopher in the 20th century, although at the same time he’s one of the least known. He’s influential not only in the world of ideas but also in the world of politics. In fact, he’s had an enormous influence on the post-Second World War global economic and political order that we live in today. People sometimes call it the “New World Order.” It’s very much influenced by his thought and action.

Kojève claimed that history is not about to end, but that it had already ended, and that it ended in 1806. So, all of the expectant people who are waiting for the millennium have already missed it. History is already over. It’s been over for nearly two centuries, and it came to an end in 1806 when Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was sitting in his study in Jena writing his book Phenomenology of Spirit and nearby Napoleon was defeating his enemies at the great Battle of Jena, which turned the tide of resistance in Europe toward the ideas of the French Revolution.

According to Kojève, history ended with the triumph of the ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity and Hegel’s understanding of the significance of these events. Everything that’s happened since then, he said, including the two World Wars, is just post-historical “mopping up.” It’s of no real historical significance. It’s just a matter of carrying the ideals of the French Revolution to the furthest corners of the globe.

Last night I saw a trailer for a film called The Cup, which is set in Bhutan in the Himalayas. This is a movie about the mopping-up process. It’s about some intrepid young Buddhist monks who fall in love with soccer and decide to bring satellite television to Bhutan. According to Kojève, this is just the kind of mopping-up process you’d expect as the world becomes completely integrated and its culture becomes entirely homogenized. Of course, this is presented as a heart-warming tale of intrepid youth.

Now, who was Alexandre Kojève? He was born in 1902 as Aleksandr Vladimirovič Koževnikov. He was born in Moscow to a very wealthy family. After the Russian Revolution, the family fell on hard times, and he was eventually reduced to selling black-market soap on the street. He was arrested for this and narrowly escaped execution. His experiences with the GPU led to a rather unusual outcome. He converted to Marxism and maintained that he was an ardent Stalinist to the very end of his life.

Now, who was Alexandre Kojève? He was born in 1902 as Aleksandr Vladimirovič Koževnikov. He was born in Moscow to a very wealthy family. After the Russian Revolution, the family fell on hard times, and he was eventually reduced to selling black-market soap on the street. He was arrested for this and narrowly escaped execution. His experiences with the GPU led to a rather unusual outcome. He converted to Marxism and maintained that he was an ardent Stalinist to the very end of his life.

In 1920, ardent Marxist-Stalinist that he was, he still saw fit to flee the Soviet Union to Germany. He enrolled at the University of Heidelberg, studying philosophy with the great German existentialist thinker Karl Jaspers, and he wrote a dissertation on Vladimir Soloviev, a Russian mystical philosopher of some interest, although he is rather unknown in the West.

Apparently, the Koževnikovs had money abroad, so while he was in Germany Kojève was actually something of a bon vivant. He lived the high life. He was a sort of limousine Stalinist. But he invested his family money poorly, and in 1929 he was pretty much wiped out by the great stock market crash.

In that year, he moved to France and started trying to find work. He had many friends, Russian émigrés, who helped him out. One of them was Alexandre Koyré, who was a historian of philosophy and science who had to go off to Egypt as a visiting professor and got Kojève the job in 1933 of subbing for him in a seminar on Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit.

Kojève did such a spectacular job that he gave the seminar every year until 1939, when the Germans moved in and French intellectual life changed somewhat. Kojève spent the war in the south of France, writing, and some of the works that he wrote during the war were published posthumously. He probably sat out the war because he realized that it was of no historical significance.

In 1945, he returned from his exile and was immediately given a position in the French Ministry of Economic Affairs, the head of which had been a student in his Hegel seminar during the 1930s.

From 1945 to 1968, he held the same position, a kind of undersecretary position, yet while he did not have any official leadership role, he was—as one person who knew him put it—the Mycroft Holmes of the French government. He was the guy who knew everything and everybody, and kept everybody abreast of everything else. He was a nerve center or brain center for the French government for a period of more than 20 years.

He claimed, in his typically hyperbolic style, that de Gaulle took care of foreign affairs, and “I, Kojève,” as he put it, “took care of everything else.” And apparently Raymond Aron, who was another of his students and an extremely sober fellow, actually said that this was pretty much true, that Kojève was probably second only to de Gaulle in importance in the French government in the 22 years that he occupied his position.

And what did he do? Well, he was one of the architects of what’s now called the European Economic Community. He was also one of the architects of what is known as the General Agreement on Trades and Tariffs, or GATT.

Right after the Second World War, he gave a speech to a bunch of technocrats in West Germany, where he laid out the model for what was then called pejoratively “neo-colonialism.” In his terms, colonialism after the Second World War and the end of the old colonial empires would now take the form not of taking, but of giving, namely of investing in and developing the underdeveloped countries, the former colonies, and integrating them into the world economic system. His model was basically carried out to a T. Organizations like the World Bank basically follow to this day the Kojèvian model of neo-colonialism.

He was also the first person to announce what is sometimes called the convergence thesis. Zbigniew Brzezinski, National Security Adviser to Jimmy Carter, is often credited with this view. The convergence thesis is basically that as the Cold War wore on, the pressures of fighting it would cause both sides to gradually converge and become indistinguishable from one another.

He was also the first person to announce what is sometimes called the convergence thesis. Zbigniew Brzezinski, National Security Adviser to Jimmy Carter, is often credited with this view. The convergence thesis is basically that as the Cold War wore on, the pressures of fighting it would cause both sides to gradually converge and become indistinguishable from one another.

Kojève was instrumental in creating—through the economic and political integration of the Western, non-Communist nations—one of the most important factors in helping them win the Cold War, but the French intelligence service believed that he was passing information to the KGB the whole time. So he was playing both sides in a very dangerous game. I want to give some suggestions about what Kojève’s dangerous game actually was.

Before I do that, though, I want to talk about his influence in the world of ideas. I’ve talked about his political activity. Really, of all the philosophers in the 20th century, he’s had the most impressive record of actually changing the world instead of just theorizing about it. Much of the world that we know today and think of as normal was influenced by this strange Russian. So, we need to understand the ideas behind his actions.

Kojève’s students at his Hegel seminar in the 1930s included the following people: Raymond Aron, who was probably the most brilliant conservative political theorist in France in the 20th century; Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who was something of a Marxist-Stalinist at one time and one of the most significant phenomenological philosophers in 20th-century France; Jacques Lacan, the great interpreter of Freud, who fused Freud with Kojève’s Hegel and is probably the leading Freudian thinker after Freud; Henry Corbin, who made the first (partial) French translation of Heidegger’s Being and Time but is far more famous for the work that he did in medieval Arabic philosophy and mysticism; Robert Marjolin, who was the leader of the French Ministry of Economic Affairs, the guy who gave Kojève his job; Gaston Fessard, who was little-known outside France but was an extraordinary scholar and a Jesuit priest as well; André Breton, who was one of the founders of French Surrealism; Georges Bataille, famous for writing really rather gross and I think quite untitillating pornography, as well as many books and essays on the philosophy of culture—a rather profound although difficult and quite perverted thinker; and Raymond Queneau, a novelist whose most famous novels are translated as The Sunday of Life and Zazie in the Metro—these are “end of history” novels and were very much influenced by Kojève’s vision of life at the end of history.

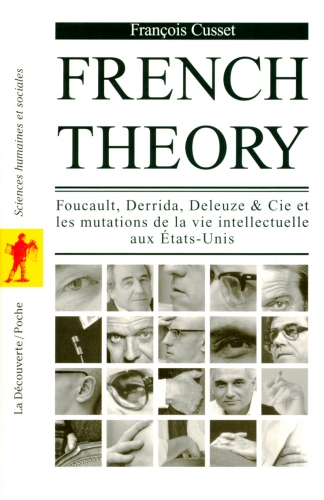

And of course these members of the seminar in turn had their own students and readers. Among them are some of the most important 20th-century French thinkers of the next generation: Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, Jean-François Lyotard, and the like. None of them were students of Kojève himself, but I would maintain that nobody can really understand these French postmodernists—especially their use of certain words like “metaphysics,” “modernity,” “difference,” and “negativity”—without understanding how all of these derive from Kojève’s interpretation of Hegel. The peculiar vehemence with which terms like “metanarrative,” “history,” “being,” “absolute knowledge,” and so forth are spoken by these writers has everything to do with Kojève’s specific interpretation of the meaning of these terms in Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. One can’t read French postmodernism and understand it without understanding that most of these thinkers are reacting to Kojève. They would not call themselves Kojèvians. They’re all anti-Kojèvians. But insofar as they’re opposing themselves to him and to his very peculiar takes on things, they’re very much influenced by him. They bear the trace of Kojève.

Another contemporary thinker who’s really quite trendy today is the Slovene writer Slavoj Žižek. I hope there are no Slovenians in the audience who will knock my pronunciation. Žižek has written quite a number of books with titles like Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Lacan . . . But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock, and he’s enormously influenced by Kojève’s view of Hegel, and also Lacan’s reading of Kojève’s Hegel.

Another contemporary thinker who’s really quite trendy today is the Slovene writer Slavoj Žižek. I hope there are no Slovenians in the audience who will knock my pronunciation. Žižek has written quite a number of books with titles like Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Lacan . . . But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock, and he’s enormously influenced by Kojève’s view of Hegel, and also Lacan’s reading of Kojève’s Hegel.

Kojève attracted students even after he stopped teaching. Two of them were Allan Bloom, the author of The Closing of the American Mind, and Stanley Rosen, who is a very well-known commentator on Greek philosophy, as well as on Hegel and Heidegger. Their teacher, Leo Strauss, sent them to study with Kojève in the early 1960s. Bloom and Rosen would go to his office at the Ministry. He would close the door, and they would talk philosophy.

More recently, Francis Fukuyama, who was a student of Allan Bloom, became famous for his book The End of History and the Last Man, which is really a popularization of Kojèvian ideas. Just as the Communist regimes in Eastern Europe were coming down, Fukuyama raised the question: What if Kojève was wrong and history hadn’t ended in 1806, as Hegel wrote the Phenomenology of Spirit? What if history ended in 1989, as Communism fell and Fukuyama was in the process of interpreting it as the global triumph of Western liberal democracy? That started a huge debate.

Of course, people on the Right in America were particularly delighted to hear that their perseverance in the Cold War had brought about not just the end of Communism but the end of history itself, and everything would be smooth sailing from then on. Little things like the Gulf War were just mopping-up.

Some of Kojève’s peers—people that he corresponded with and interacted with and influenced him—include Leo Strauss, who is one of the most important 20th-century philosophers. He was a German-Jewish philosopher who met Kojève in the 1920s. They met again in Paris in the 1930s, where they spent a lot of time together, and they corresponded throughout the rest of their lives. Strauss, of course, was a conservative thinker, a thinker of the Right, and yet he derived both pleasure and knowledge from his friendship with Kojève, the ardent Stalinist.

Carl Schmitt was the notorious German jurist and political philosopher who wrote the brief showing how Hitler’s seizure of power in 1933 was perfectly legal according to the Weimar constitution—which was indeed a brief anybody could have written because, strictly speaking, it was legal. Schmitt, of course, had been tarred with the Nazi association until he died at a very old age recently. Schmitt was a friend of Kojève’s, and they corresponded over a period of many decades. Another improbable intellectual friendship.

Georges Bataille was not just a student of Kojève, but really a

Lévi-Strauss fut-il un progressiste ?

Lévi-Strauss fut-il un progressiste ? Pour Lévi-Strauss, il n’y avait certes pas un seul système de parenté, de type monogamique occidental (c’est en cela qu’il était « tiers mondiste ») mais tous les systèmes de parenté n’étaient pas pour autant possibles. L’humanité a dressé de manière inconsciente une sorte de tableau de Mendeleieff des systèmes de parenté et il est condamné à aller de l’un à l’autre, sans échappatoire. Même chose pour Lacan : la castration du désir œdipien primitif est une constante de l’homme, un destin originel auquel nul n’échappe. Le pessimisme de Lacan — prolongement de celui de Freud — était exprimé en termes suffisamment cryptés pour qu’un public soixante-huitard avide de nouveautés mais ne comprenant pas bien ce qu’il disait lui fasse une ovation.

Pour Lévi-Strauss, il n’y avait certes pas un seul système de parenté, de type monogamique occidental (c’est en cela qu’il était « tiers mondiste ») mais tous les systèmes de parenté n’étaient pas pour autant possibles. L’humanité a dressé de manière inconsciente une sorte de tableau de Mendeleieff des systèmes de parenté et il est condamné à aller de l’un à l’autre, sans échappatoire. Même chose pour Lacan : la castration du désir œdipien primitif est une constante de l’homme, un destin originel auquel nul n’échappe. Le pessimisme de Lacan — prolongement de celui de Freud — était exprimé en termes suffisamment cryptés pour qu’un public soixante-huitard avide de nouveautés mais ne comprenant pas bien ce qu’il disait lui fasse une ovation.

THE Glass Bees is an introspective novel about a quiet but dignified cavalry officer called Richard. Unable to adjust to life after war and needing money, he applies for a security job at the headquarters of the mysterious oligarch Zapparoni. Confronted with mechanical and psychological trials, the dream becomes a nightmare, and Richard is forced to contemplate his place in the

THE Glass Bees is an introspective novel about a quiet but dignified cavalry officer called Richard. Unable to adjust to life after war and needing money, he applies for a security job at the headquarters of the mysterious oligarch Zapparoni. Confronted with mechanical and psychological trials, the dream becomes a nightmare, and Richard is forced to contemplate his place in the

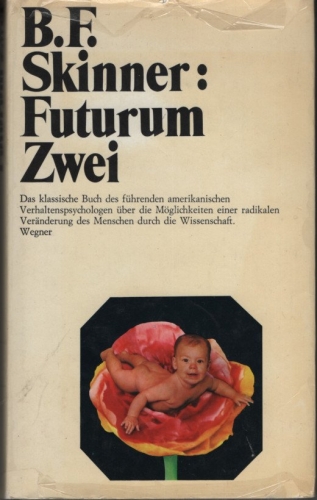

Le psychologue B.F. Skinner a par exemple écrit l'utopie "Futurum 2"/"Walden Two", qui représente un État communiste fonctionnant sur la base d'un lavage de cerveau des citoyens du berceau à la tombe [4]. La dystopie d'Aldous Huxley "Le Meilleur des mondes" décrit les mêmes principes que le livre de Skinner, mais ici au service d'une société consumériste dirigée par une entreprise géante [5].

Le psychologue B.F. Skinner a par exemple écrit l'utopie "Futurum 2"/"Walden Two", qui représente un État communiste fonctionnant sur la base d'un lavage de cerveau des citoyens du berceau à la tombe [4]. La dystopie d'Aldous Huxley "Le Meilleur des mondes" décrit les mêmes principes que le livre de Skinner, mais ici au service d'une société consumériste dirigée par une entreprise géante [5].

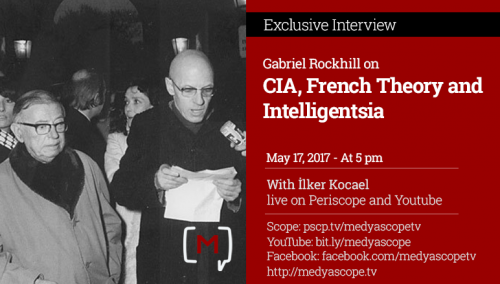

L’interprétation de la French theory par la CIA devrait nous faire réfléchir, dans ce cas, à reconsidérer le vernis radical chic qui a accompagné en grande partie sa réception anglophone. Selon une conception étapiste d’une histoire progressiste (généralement aveugle à sa téléologie implicite), l’œuvre de figures comme Foucault, Derrida et d’autres théoriciens français d’avant-garde est souvent intuitivement associée à une forme de critique radicale et sophistiquée qui dépasse sans doute de loin tout ce que l’on trouve dans les traditions socialistes, marxistes ou anarchistes. Il est certainement vrai, et mérite d’être souligné que la réception anglophone de la French theory, comme John McCumber l’a souligné à juste titre, a eu d’importantes implications politiques en tant que pôle de résistance aux fausses neutralités politiques, aux formalismes techniques rassurants de la logique et du langage, ou au conformisme idéologique direct opérant dans la tradition philosophique anglo-américaine et soutenu par McCarthy. Cependant, les pratiques théoriques des philosophes qui ont tourné le dos à ce que

L’interprétation de la French theory par la CIA devrait nous faire réfléchir, dans ce cas, à reconsidérer le vernis radical chic qui a accompagné en grande partie sa réception anglophone. Selon une conception étapiste d’une histoire progressiste (généralement aveugle à sa téléologie implicite), l’œuvre de figures comme Foucault, Derrida et d’autres théoriciens français d’avant-garde est souvent intuitivement associée à une forme de critique radicale et sophistiquée qui dépasse sans doute de loin tout ce que l’on trouve dans les traditions socialistes, marxistes ou anarchistes. Il est certainement vrai, et mérite d’être souligné que la réception anglophone de la French theory, comme John McCumber l’a souligné à juste titre, a eu d’importantes implications politiques en tant que pôle de résistance aux fausses neutralités politiques, aux formalismes techniques rassurants de la logique et du langage, ou au conformisme idéologique direct opérant dans la tradition philosophique anglo-américaine et soutenu par McCarthy. Cependant, les pratiques théoriques des philosophes qui ont tourné le dos à ce que