mardi, 13 octobre 2015

Dostoevsky: Demonic Rationalism

Dostoevsky: Demonic Rationalism

In his work Dostoevsky and the Metaphysics of Crime, sociologist Dr. Vladislav Arkadyevich Bachinin analyzes the only seemingly contradictory correlation between Enlightenment rationalism and the rise of infernal forces in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s work Demons. Translated by Mark Hackard.

Ex: http://souloftheeast.org

The Immoral Reason of a Living Automaton

Pyotr Verkhovensky, the cold-blooded cynic who easily transgresses any moral obstacles, represents a special type of criminal, to whom is applicable the philosophical metaphor of “man the machine.”

In 1748 France, Lematrie’s book under that title was released. Its author cast man as a self-winding machine moving along perpendicular lines. In Lametrie’s conception a human being was the direct likeness of a watch or harpsichord, and at the same time subordinated to natural necessity. But possessing instincts, feelings, and passions, he is deprived of a soul. Lametrie assumed that the soul was a term lacking any essential substance whatsoever.

The world in which the machine-man dwells is anthropocentric; there is no place for God. Reality is arranged in accordance with the principles of Newtonian mechanics, and the world presents a mechanical conglomerate of soulless elements. Natural and social processes are moved by one and the same mechanical forces.

The philosophy of machine rationality unfolds as the unique result of the evolution of classical rationalism. The elimination of all metaphysical content prepares the ground both for the arrival of positivism and for the realization of plans for building the future strictly rationalized society with calculated parameters wholly under the control of a directing will. The machine-man and machine-state, which need each other, arise as something resembling Aristotle’s telic reasons, and will directly and gradually determine the development of positivist anthropocentric schematics.

In accordance with the mechanistic picture of the world, there always exists the threat of intentional deformations in the structures of the cosmic order. Objectively there exist possibilities for the violation of measure and harmony, the destruction of order, and the ascent of chaos. A murderer can realize the objective possibility of death that exists for his victim. A thief or robber is capable of realizing the objective possibility of shifting material values in the social space from one set of hands to the other, etc. That is, it stands only for man to apply certain efforts for the possibility of disintegration of existing structures, its movement into reality. At times purely mechanical forces were sufficient for this. Moreover, the higher the degree of mechanism of such enterprises, the less that spiritual, ethical, religious, and similar components are in the mix, and the more effective destructive actions will prove.

Dostoevsky has the philosophy of the machine-man applicable first and foremost to characters who represent practical businessmen smacking of commercial types of the Western model, i.e., to such men as Luzhin, Rakitin, Epanchin, Totsky, Ferdyshchenko, etc. Indifferent to metaphysical reality, they subscribe to Rousseau’s “Geneva ideals” allowing the possibility of “virtue without Christ.” Immersed in the vanity of a graceless, prosaic-pragmatic existence, “having ears, they do not hear, and having eyes, they do not see.” All that comes from on high, from the spheres of metaphysical reality, does not reach their souls, and therefore they are immersed in the darkness of ignorance and incomprehension of the most important meanings of life. The thoughts and feelings of these “Bernards” carry an earthly character and are not directed toward the beyond. They do not like abstract reasoning, considering it an idle pastime. For them as for Lametrie, God and the soul are false moral magnitudes. For them the entire world dwells in the “disenchanted” state of a gigantic conglomerate of soulless elements. Not in one of them does God’s spark gleam. All these men are spiritually impoverished living machines, wound up, however, by a mysterious hand, but as Lev Shestov would say about them, they are not conscious that their life is not life, but death.

In his portrayals Dostoevsky expounds his criticism of the far-from-clean, wholly filthy immoral mind, more precisely the banal and base “Euclidian” reason that is deaf to the metaphysics of moral absolutes, the mind that sees in the soul “only vapor;” that is governed by cold reason alone and views the entire world as a set of tools for the achievement of its vapid objectives.

Among the specimens of the machine-man replicated by Dostoevsky, Pyotr Verkhovensky represents the most odious exemplar. He is calculating, ruthless, and is ready to go the full distance for the achievement of his goals, not stopping at the most vile infamies and crimes.

Criminal reality, inside of which exists Verkhovensky’s true “I,” is distinguished by characteristics such as a harsh aloofness from other evaluative worlds, and most of all from the world of religious, moral, and natural-law absolutes. Second, inherent to it is an acute tension in relations with official-normative evaluative reality. And its third particularity is a faint vulnerability, explained by the fact that for all its antagonistic position, it aspires to copy the structures of legal realities in its own fashion. Just as the devil parodies God, trying to imitate him, the criminal world seeks, for all the caricatured nature of its efforts, to reproduce normative-evaluative stereotypes of the legitimate and sacral worlds, attempting to acquire additional vitatlity at their cost.

It is not accidental that Shatov’s murder in Demons bears the marks of a ritual sacrifice. Along with that it takes the form of a monstrous parody of ancient ritual: instead of the solemnity of a holy rite, there is the filthy lowness of the whole scene; instead of open officiality, there is the cowardly, concealed secret act; instead of calling upon the favor of higher forces, there is a wager on the dark elements of evil, a commiseration of all the participants of the murder through the spilled blood of the victim and mutual fear before one another.

The Normative Space of the Criminal-Political Association

Verkhovensky deliberately forms an enclosed normative-evaluative space of criminal-corporate “morality” with harsh principles of self-organization and self-preservation. He requires that association members’ attitude to their tasks and objectives be extremely serious, not allowing for skepticism, self-irony, or criticism. Violators are immediately punished. Applied violence fulfills a protective function, acting as a means of welding and self-defense for this artificial micro-world.

Aside from similarity in the structure and forms of activity of criminal-political and purely criminal organizations, between the two there are essential distinctions. And so, if a criminal group’s ultimate goals are limited to the resolution of self-interested mercantile tasks, then the goals of criminal-political associations reach far beyond the boundaries of mercantile interests and are oriented toward the achievement of political dominance, by which members of the association cross over into the position of a ruling elite.

If associated criminals, as a rule, do not issue a challenge to the state and the state system but prefer to deal with individual citizens, a criminal-political association boldly steps into antagonism with state power and its institutions.

If a criminal group represents a unique form of a “thing-for-itself” and doesn’t conceal its corporate egoism, then a criminal-political association masks its just-as-base interests with a smokescreen of lies about the interests of the people that supposedly concern it.

The latter circumstance, noted Dostoevsky, allowed such men as Verkhovensky to recruit supporters not only from the spectrum of little-educated “losers” and fanatics with an unhealthy lust for intrigue and power, but also to involve young people with a good heart, even if with a “shakiness” in their views. The fate of the latter proved genuinely tragic, since these confidence tricksters, who studied the magnanimous side of the human heart and were able to play on its strings as on a musical instrument, ultimately transformed these youth into criminals.

Dostoevsky lamented that contemporary youth was undefended against “demonism” through maturity of firm convictions and moral hardiness. Among many material drives dominate a higher idea, and a genuine education is replaced with stereotypes of impudent negation through another’s voice, dissatisfaction, and impatience. As a result “even an honest and guileless boy, even one who studied well, could occasionally turn out to be a Nechaevite…that is, again, if he’d come across Nechaev…” (21, 133). To such boys, Nechaevs and Verkhovenskys paint criminal acts as feats of policy.

The fateful transformations that took place in the souls of many “Russian boys” were facilitated by a “time of troubles” itself, which forced Russian civilization at first slowly, and then ever more quickly, to slide down a sloping surface leading from order to chaos.

“In my novel Demons,” wrote Dostoevsky, “I attempted to attempted to express those various and diverse motives by which even the purest of heart and the most guileless people can be drawn to commit the most monstrous villainy. Therein is the horror, that here one can do the most infamous and abhorrent deed, sometimes completely not being a scoundrel! And that’s not among us only, but across the whole world it is so, always and from the beginning of the ages, during times of transition, in times of dislocation in people’s lives, of doubts and negation, skepticism and unsteadiness in basic social convictions. But we have it more than it’s possible anywhere, and namely in our time, and this feature is the most painful and sad feature of our present time. In the possibility of seeing oneself, and even sometimes almost, as a matter of fact, as not a scoundrel, while working clear and inarguable abomination – herein is our contemporary tragedy!” (21, 131)

“Machine” Rationality of a Political Program

Verkhovensky, possessing a strong, mechanical will seeking power, found a just as machine-like political program that corresponded to his nature. Its basic positions amount to the following points:

- A new type of state with predominantly totalitarian forms of rule is necessary.

- This state should keep its subjects in constant terror, without ceasing, conducting surveillance of everyone “every hour and every minute.”

- Since geniuses, talents, and striking individuals represent a threat to the power of “machine-like” leaders by their extraordinary nature, all people will brought to an average level in their development through ideological and police terror, in the course of which Ciceros will have their tongues ripped out, Copernicuses their eyes gouged, Shakespeares stuck down with stones, etc.

- To come to enactment of this program, it is necessary to begin with the total destruction of everything, in practice carrying out the transition from order to chaos.

Two vectors have united in this criminal-political program – the “machine” rationality of soulless villains with the demonic irrationality of maniacs run amok.

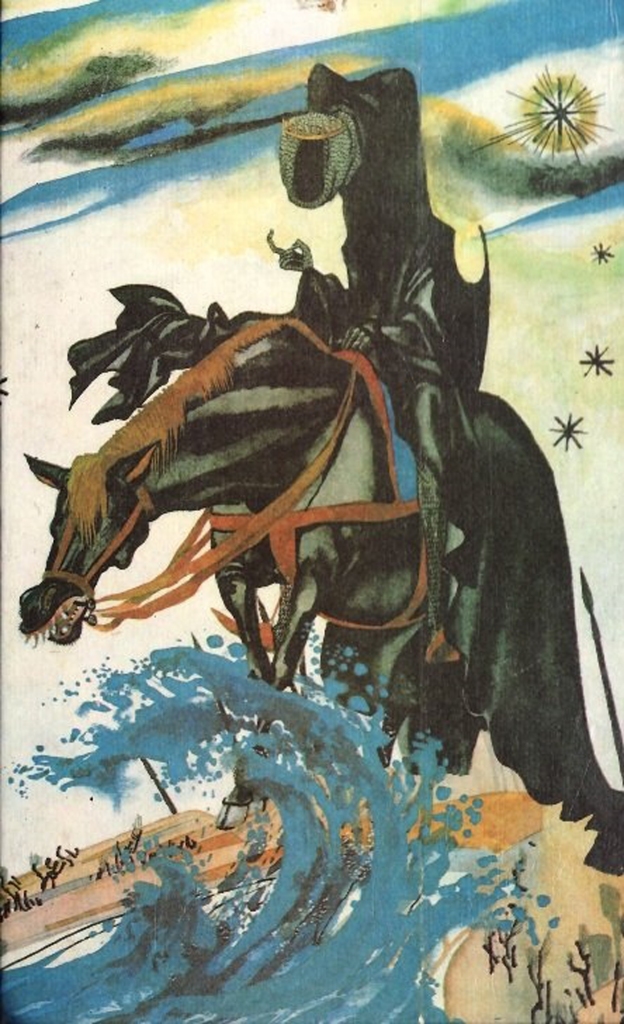

One of the most impressive paradoxes of Verkhovensky’s personality is just that surprising combination of “machine likeness” with a maniacal enthusiasm for destruction. It accords the figure of the political fiend an especially sinister character. With the direct participation of this unfeeling “machine” for producing disorder, events in the novel take the form of an oncoming squall, chaos enthroned, when a dozen murders and suicides are committed, along with several bouts of madness and a grandiose fire from arson. As a result the world enclosed in the novel’s textual frame begins to resemble a monstrous bestiary, where there is an absence of love and mercy, where there is only ruthless struggle of all against all.

Dostoevsky saw one of the sources of this chaos in the philosophical mindsets of rationalistic, materialistic, and atheistic content that penetrated from the West. Falling on Russian soil, the doctrines of Darwin, Mill, Strauss, and other representatives of European “progressive” thought, as a rule were taken in the Slavic consciousness, untried by many centuries of philosophical schooling, as adamantine philosophical axioms. Moreover, practical conclusions were often drawn from them, conclusions the possibility of which Western teachers had not suspected.

Of course, positive knowledge did not directly teach anyone villainy. And if Strauss, Dostoevsky notes with unconcealed irony, denied and mocked Christ, alongside that for man and humanity he demonstrated the most earnest love and desired their most radiant future.

But then here is what seems to me indubitable – give all these contemporary higher teachers the full opportunity to destroy the old society and build a new one – then there will come such darkness, such chaos, something so crude, blind, and inhuman, that the whole construction would collapse under the curses of humanity before it could be completed. Once it has rejected Christ, the human mind can reach the most astounding results. That is an axiom. Europe, at least in the higher representations of its thought, rejects Christ, and as is known, we are obligated to imitate Europe. (21, 132-133)

For Dostoevsky the evaluative-orienting and practical-transforming activity of moral, legal, and political consciousness must be founded on the principles of Theo-centrism. He disseminates the spirit of Theodicy on all spheres of spheres of social and spiritual life without exception. The Western legal consciousness is predominantly anthropocentric, and as a rule does not accept either religious or metaphysical normative-evaluative bases.

These bases are unneeded by machine-man, who discovers by his actions that open immorality, crime, and political Machiavellianism all have one and the same nature. They all begin with the denial of higher principles of being, absolute values, and norms.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, russie, dostoïevski, littérature, lettres, lettres russes, littérature russe |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les commentaires sont fermés.