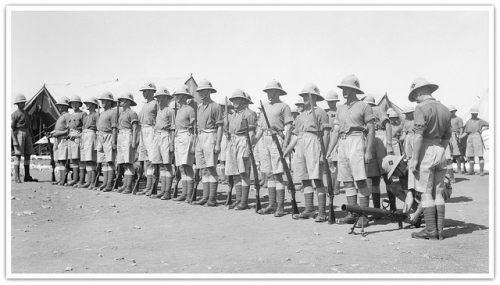

When the British armed forces occupied the Middle East at the end of the war, the region was passive.

From chapter 43: “The Troubles Begin: 1919 – 1921”; A Peace to End All Peace, David Fromkin

With this sentence, Fromkin begins his examination of the troubles for western imperialists throughout the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia. Of course, there were interventions before this time (Britain already had significant presence in Egypt and India, for example), yet – corresponding with the overall theme of Fromkin’s book – his examination centers on the aftermath of the fall of the Ottoman Empire.

Fromkin summarizes the situation and conflict in nine different regions (many of which were not “countries” as we understand the term). He suggests that the British did not see a connection in these difficulties, one region to the other:

In retrospect, one sees Britain undergoing a time of troubles everywhere in the Middle East between 1919 and 1921; but it was not experienced that way, at least not in the beginning.

As I have found repeatedly throughout this book, while history might not repeat, it rhymes so obviously that one could suggest plagiarism.

This is a long post – 3500 words; for those who want the summary, I offer the following: Egypt, Afghanistan, Arabia, Turkey, Syria and Lebanon, Eastern Palestine (Transjordan), Palestine – Arabs and Jews, Mesopotamia (Iraq), Persia (Iran).

Promises made during war, promises broken during the peace; local factions at odds with each other; most factions at odds with the imperialists; intrigue and double-dealing; fear of the Bolshevik menace; costly wars and occupations; the best laid plans of mice….

There you have it – you can skip the details if you like. Alternatively, just pick up a copy of today’s paper.

Egypt

…Britain had repeatedly promised Egypt her independence and it was not unreasonable for Egyptian politicians to have believed the pledges…

These were useful promises to make during the war; they became a source of conflict after:

Neither negotiations nor independence were what British officials had in mind at the time.

Britain allowed no delegation from Egypt to go to either London or Paris during 1918. When Egyptian officials protested their exclusion from the Paris peace conferences of 1919, the British deported the lead delegate, Saad Zaghlul, and three of his colleagues to Malta.

A wave of demonstrations and strikes swept the country. The British authorities were taken by surprise.

Telegraph communications cut, attacks on British military personnel ensued – culminating, on March 18, with the murder of eight of them on a train from Aswan to Cairo. Christian Copts demonstrated alongside Moslems; theological students alongside students from secular schools; women (only from the upper classes) alongside men. Most unnerving to the British: the peasantry in the countryside, the class upon whom British hopes rested.

Britain returned Zaghlul from Malta, and negotiated throughout the period 1920 – 1922. The process yielded little, and Zaghlul once again was deported.

The principal British fantasy about the Middle East – that it wanted to be governed by Britain, or with her assistance – ran up against a stone wall of reality. The Sultan and Egypt’s other leaders refused to accept mere autonomy or even nominal independence; they demanded full and complete independence, which Britain – dependent on the Suez Canal – would not grant.

British (continuing with American) domination has been maintained more or less ever since.

Afghanistan

The concern was (and presumably remains) containing and surrounding Russia – the Pivot Area of Mackinder’s world island:

The issue was believed by British statesmen to have been resolved satisfactorily in 1907, when Russia agreed that the [Afghan] kingdom should become a British protectorate.

Apparently no one asked the locals: after the Emir of Afghanistan was assassinated on 19 February 1919, his third son – 26-year-old Amanullah Khan – wrote to the Governor-General of India…

…announcing his accession to the “free and independent Government of Afghanistan.”

What came next could be written of more recent times: Afghan attacks through the Khyber Pass, the beginning of the Third Afghan War. Further:

For the British, the unreliability of their native contingents proved only one of several unsettling discoveries…

…the British Government of India was obliged to increase its budget by an enormous sum of 14,750,000 pounds to cover the cost of the one-month campaign.

…the British forces were inadequate to the task of invading, subduing, and occupying the Afghan kingdom.

What won the day for them was the use of airplanes…it was the bombing of Afghan cities by the Royal Air Force that unnerved Amanullah and led him to ask for peace.

In the ensuing treaty, Afghanistan secured its independence – including control of its foreign policy. Amanullah made quick use of this authority by entering into a treaty with the Bolsheviks. Britain attempted to persuade Amanullah to alter the terms of the treaty…

But years of British tutelage had fostered not friendship but resentment.

Arabia

Of all the Middle Eastern lands, Arabia seemed to be Britain’s most natural preserve. Its long coastlines could be controlled easily by the Royal Navy. Two of its principal lords, Hussein in the west and Saud in the center and east, were British protégés supported by regular subsidies from the British government.

No European rival to Britain came close to holding these advantages.

Yet, these two “protégés” were “at daggers drawn” – and Britain was financially supporting both sides in this fight. A decision by the British government was required, yet none was forthcoming – different factions in the government had different opinions; each side in Arabia had its supporters in London; decisions were made in one department, and cancelled in another.

Ibn Saud was the hereditary champion of Muhammed ibn Abdul Wahhab; in the eighteenth century, Wahhab allied with the house of Saud, reinforced through regular intermarriage between members of the two families.

The Wahhabis (as their opponents called them) were severely puritanical reformers who were seen by their adversaries as fanatics. It was Ibn Saud’s genius to discern how their energies could be harnessed for political ends.

Beginning in 1912, tribesmen began selling their possessions in order to settle into cooperative agricultural communities and live a strict Wahhabi religious life

The movement became known as the Ikhwan: the Brethren. Ibn Saud immediately put himself at the head of it, which gave him an army of true Bedouins – the greatest warriors in Arabia.

It was the spread of this “uncompromising puritanical faith into the neighboring Hejaz” that threated Hussein’s authority. The military conflict came to an end when a Brethren force of 1,100 camel riders – armed with swords, spears, and antique rifles – came upon the sleeping camp of Hussein’s army of 5,000 men – armed with modern British equipment – and destroyed it.

Britain intervened on Hussein’s behalf. Ibn Saud, ever the diplomat, made a show of deferring to the British and “claimed to be trying his best to restrain the hotheaded Brethren.” Meanwhile, Saud and his Wahhabi Brethren went on to further victories in Arabia. Ultimately, Ibn Saud captured the Hejaz and drove Hussein into exile.

Yet the British could do nothing about it. As in Afghanistan, the physical character of the country was forbidding.

There was nothing on the coast worth bombing; Britain’s Royal Navy – its only strength in this region – was helpless.

Turkey

Lloyd George changed his mind several times about what to do with Turkey. Ultimately decisions were taken out of his hands via the work of Mustapha Kemal – the 38-year-old nationalist general and hero. He began by moving the effective seat of government power inland and away from the might of the Royal Navy – to Angora (now Ankara).

In January 1920, the Turkish Chamber of Deputies convened in secret and adopted the National Pact, calling for creation of an independent Turkish Moslem nation-state. In February, this was announced publicly. While Britain and France were meeting in Europe to discuss the conditions they would impose on Turkey, the Chamber of Deputies – without being asked – defined the minimum terms they were willing to accept.

It was estimated that twenty-seven army divisions would need to be provided by the British and French to impose upon the terms which were acceptable in London and Paris. This was well beyond any commitment that could be made. Still, Lloyd George would not concede.

France attempted to come to terms with the Turks. Britain would not, leading an army of occupation into Constantinople. France and Italy made clear to the Turks that Britain was acting alone.

Britain’s occupation of Constantinople did not damage Kemal – 100 members of the Chamber of Deputies who remained free reconvened in Angora, and with 190 others elected from various resistance groups, formed a new Parliament.

Treaties with Russia ensued – misread by Britain as an alliance. Instead, Kemal – an enemy of Russian Bolshevism – suppressed the Turkish Communist Party and killed its leaders. Stalin, recognizing that Kemal could inflict damage to the British, put Russian nationalism ahead of Bolshevik ideology and therefore made peace. Soviet money and supplies poured over the Russo-Turkish frontier to the anti-Bolshevik Nationalists for use against the British.

Britain – acting at least in part on their misreading of the Russo-Turkish actions – threw in with the Greeks, a willing party desiring to recover former Greek territory populated throughout by a Greek minority.

Kemal attacked British troops in Constantinople. London recognized that the only troops available to assist were the Greeks. Venizelos agreed to supply the troops as long as Britain would allow him to advance inland. Lloyd George was more than willing to agree.

The Greeks found early success, advancing to the Anatolian plateau:

“Turkey is no more,” and exultant Lloyd George announced triumphantly. On 10 August 1920 the Treaty of Sèvres was signed by representatives of the virtually captive Turkish Sultan and his helpless government.

Helpless because it was Mustapha Kemal in charge, not the Sultan.

The treaty granted to both Greece and London all that each was seeking. Yet, how to keep the terms from being overthrown by the reality on the ground? Without a continued Allied presence, Kemal might well descend from the Anatolian plateau and retake the coast.

Meanwhile, the pro-British Venizelos lost an election to the pro-German Constantine I (there is a deadly monkey bite involved in this intrigue). This turnabout opened the possibility for those who desired to abandon this quagmire to do so. Italy and France took advantage of this; Lloyd George did not. Again, incorrectly viewing Kemal as a Bolshevist ally, Lloyd George could not compromise on his anti-Russian stand.

The Greeks went for total victory and lost, ending in Smyrna. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk – “Father of the Turks” – is revered to this day for securing the ethnically- and religiously-cleansed Turkish portion of the former Ottoman Empire.

Syria

Feisal – who led the Arab strike force on the right flank of the Allied armies in the Palestine and Syria campaigns – was the nominal ruler of Syria. Feisal – a foreigner in Damascus – spent much of 1919 in Europe negotiating with the Allies. In the meantime, intrigue was the order of the day in Damascus.

The old-guard traditional ruling families in Syria were among those whose loyalty to the Ottoman Empire had remained unshaken throughout the war. They had remained hostile to Feisal, the Allies, and the militant Arab nationalist clubs…

In mid-1919, the General Syrian Congress called for a completely independent Syria – to include all of the area today made up of Syria, Lebanon, Israel and Jordan. Matters seemed to be passing out of Feisal’s control. France was willing to grant some autonomy to Syria, but many Syrians saw no role for the French.

Intrigue followed intrigue; factions formed and dissolved. Eventually France issued an ultimatum to Feisal – one considered too onerous for Feisal to accept, yet he did. The mobs of Damascus rioted against him. By this time, the French marched on Damascus – supported by French air power.

The French General Gouraud began to divide Greater Syria into sub-units – including the Great Lebanon and its cosmopolitan mix of Christians and Moslems – Sunni and Shi’ite.

Eastern Palestine (Transjordan)

France was opposed to a Zionist Palestine; Britain, of course, was a sponsor. France opposed a Jewish Palestine more than it was opposed to a British Palestine. France had commercial and clerical interests to protect, and felt these would be endangered by a British sponsored Zionism.

The dividing lines between places such as Syria-Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan were vague at best. Where lines were drawn would make or break French interests. In British support for Zionism, France saw British desires to control ever-larger portions of this as-of-yet undefined region.

[France] also claimed to discern a Jewish world conspiracy behind both Zionism and Bolshevism “seeking by all means at its disposal the destruction of the Christian world.” …Thus the French saw their position in Syria and Lebanon as being threatened by a movement that they believed to be at once British, Jewish, Zionist, and Bolshevik….”It is inadmissible,” [Robert de Caix, who managed France’s political interests in Syria] said, “that the ‘County of Christ’ should become the prey of Jewry and of Anglo-Saxon heresy. It must remain the inviolable inheritance of France and the Church.”

Britain was not in a position to militarily defend Transjordan from a French invasion; therefore it worked to avoid provoking France. Yet, there was still the concern of the French propaganda campaign – designed to draw Arab support for a Greater Syria to include Transjordan and Palestine via an anti-Zionist platform.

Palestine – Arabs and Jews

Beginning in 1917-1918, when General Allenby took Palestine from the Turks, there was established a British military administration for the country:

Ever since then, throughout the military administration there had been a strong streak of resentment at having been burdened by London with an unpopular and difficult-to-achieve policy: the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine pursuant to the Balfour Declaration.

The Zionists emphasized their desire to cooperate with the local Arab communities; the Jewish immigrants would not be taking anything away but would buy, colonize and cultivate land that was not then being used. This desire was made more difficult given the rivalries between great Arab urban families.

As an aside, during this time – the late 19th / early 20th century – there was a movement that took root in Britain known as British Israelism:

British Israelism (also called Anglo-Israelism) is a doctrine based on the hypothesis that people of Western European and Northern European descent, particularly those in Great Britain, are the direct lineal descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes of the ancient Israelites. The doctrine often includes the tenet that the British Royal Family is directly descended from the line of King David.

At the end of the 19th century Edward Hine, Edward Wheeler Bird and Herbert Aldersmith developed the British Israelite movement. The extent to which the clergy in Britain became aware of the movement may be gauged from the comment made by Cardinal John Henry Newman (1801-1890); when asked why in 1845 he had left the Church of England to join the Roman Catholic Church, he said that there was a very real danger that the movement “would take over the Church of England.” (emphasis added)

The extent to which this effort in Britain influenced British policies toward Palestine are beyond the scope of this post, yet clearly the connection cannot be ignored.

Returning to Fromkin, from a note written by Churchill to Lloyd George on 13 June 1920:

“Palestine is costing us 6 millions a year to hold. The Zionist movement will cause continued friction with the Arabs. The French…are opposed to the Zionist movement & will try to cushion the Arabs off on us as the real enemy. The Palestine venture…will never yield any profit of a material kind.”

Mesopotamia (Iraq)

At the close of the war, the temporary administration of the provinces was in the hands of Captain (later Colonel) Arnold Wilson of British India, who became civil commissioner.

While he was prepared to administer the provinces of Basra and Baghdad, and also the province of Mosul…he did not believe that they formed a coherent entity.

Kurds of Mosul would likely not easily accept rule by Arabs of other provinces; the two million Shi’ite Moslems would not easily accept rule by the minority Sunni Moslem community, yet “no form of Government has yet been envisaged, which does not involved Sunni domination.” There were also large Jewish and Christian communities to be considered. Seventy-five percent of the population of Iraq was tribal.

Cautioned an American missionary to Gertrude Bell, an advocate of this new “Iraq”:

“You are flying in the face of four millenniums of history if you try to draw a line around Iraq and call it a political entity! Assyria always looked to the west and east and north, and Babylonia to the south. They have never been an independent unit. You’ve got to take time to get them integrated, it must be done gradually. They have no conception of nationhood yet.”

Arnold Wilson was concerned about an uprising:

In the summer of 1919 three young British captains were murdered in Kurdistan. The Government of India sent out an experienced official to take their place in October 1919; a month later he, too, was killed.

There were further murdered officers, hostage rescues, and the like. According to Colonel Gerald Leachman, the only way to deal with the disaffected tribes was “wholesale slaughter.”

In June the tribes suddenly rose in full revolt – a revolt that seems to have been triggered by the government’s efforts to levy taxes. By 14 June the formerly complacent Gertrude Bell, going from one extreme to another, claimed to be living through a nationalist reign of terror.

According to Arnold Wilson, the tribesmen were “out against all government as such…” yet this was not a satisfactory explanation, as every region of the British Middle East was in some state of chaos and revolt.

For one reason or another – the revolt had a number of causes and the various rebels pursued different goals – virtually the whole area rose against Britain, and revolt then spread to the Lower Euphrates as well.

On 11 August, Leachman, the advocate of “wholesale slaughter,” was murdered on order of his tribal host while attending a meeting with tribal allies – blowback of a most personal nature. Before putting down the revolt, Britain suffered 2,000 casualties with 450 dead.

Persia (Iran)

“The integrity of Persia,” [Lord Curzon] had written two decades earlier, “must be registered as a cardinal precept of our Imperial creed.”

The principal object of his policy was to safeguard against future Russian encroachments. Unfortunately, the means to secure this “integrity” were limited, and hindered further by mutinies and desertions in the native forces recruited by Britain. The solution was thought to be a British-supervised regime in Persia:

Flabby young Ahmed Shah, last of the fading Kadjar dynasty to sit upon the throne of Persia, posed no problem; he was fearful for his life and, in any event, received a regular subsidy from the British government in return for maintaining a pro-British Prime Minister in office.

Under the supervision of Lord Curzon, the Persians signed a treaty. The Persian Prime Minister and two colleagues demanded – and received – 130,000 pounds from the British in exchange. What was worth this payment? British railroads, reorganization of Persian finances along British lines, British loans, and British officials supervising customs duties to ensure repayment of the loans.

With the collapse of the Russian Empire, fear of the Russians faded in Persia; therefore Britain represented the only threat to the autonomy of various groups in Persia. Public opinion weighed strongly against the Anglo-Persian agreement.

Meanwhile, the Bolsheviks were courting the Persians – forgiveness of debts, renouncing of prior political a military claims, cancelling all Russian concessions and surrendering all Russian property in Persia. Of course, the Soviet government was too weak to enforce any of these claims anyway; still these gestures were seen in great contrast to the measures taken by Britain.

Nationalist opinion hardened; in the spring of 1920, events took a new turn. The Bolsheviks launched a surprise naval attack on the British position on Enzeli; Soviet troops landed and cut off the British garrison at the tip of the peninsula. The commanding general had little choice but to accept the Soviet surrender terms, surrendering its military supplies and a fleet of a formerly British flotilla – previously handed by the British to the White Russians and held by the Persians upon collapse of the Russian Empire.

Within weeks, a Persian Socialist Republic was proclaimed in the local province. Britain, having entered into the Anglo-Persian Agreement in significant measure to contain Soviet expansion, was clearly failing at this task. The War Office demanded that the remaining British forces in Persia should be withdrawn.

This was not yet to occur. In February 1921, Reza Khan marched into Tehran at the head of 3,000 Cossacks, seizing power. In a manner, this entire escapade was instigated by the British General Ironside, who had approached Reza Khan about ruling once Britain departed. Reza Khan did not wait, it seems.

Within five days, the new Persian government repudiated the Anglo-Persian Agreement. On the same day, a treaty was signed with Moscow – now looking for Russian protection from Britain instead of the other way around.

Conclusion

I don’t know – it isn’t over yet.

Reprinted with permission from Bionic Mosquito.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.