Before World War II liberal rights were understood among Western states in a libertarian and ethno-nationalistic way. Freedom of association, for example, was understood to include the right to refuse to associate with certain members of certain ethnic groups, even the right to discriminate in employment practices. This racial liberalism was still institutionalized right up until the 1960s. The settler nations of Australia, Canada, United States, and New Zealand enjoyed admission and naturalization policies based on race and culture, intended to keep these nations “White.”

This liberal racial ethos was socially accepted with a good conscience throughout Western society. As Robert H. Jackson has observed:

Before the war prevailing public opinion within Western states — including democratic states — did not condemn racial discrimination in domestic social and political life. Nor did it question the ideas and institutions of colonialism. In the minds of most Europeans, equality and democracy could not yet be extended successfully to non-Europeans. In other words, these ideas were not yet considered to be universal human rights divorced from any particular civilization or culture. Indeed, for a century or more race had been widely employed as a concept to explain the scientific and technological achievements of Europeans as compared to non-Europeans and to justify not only racial discrimination within Western states but also Western domination of non-western peoples. Racial distinctions thus served as a brake on the extension of democratic rights to people of non European descent within Western countries as well as in Western colonies. [Robert H. Jackson, “The Weight of Ideas in Decolonization: Normative Change in International Relations,” In Ideas and Foreign Policy: Beliefs, Institutions and Political Change, ed. Goldstein and Keohane, Cornell University Press, 1993, p. 135]

Even in the case of denazified Germany, governments after 1945 endorsed, as a matter of common sense, and well into the 1970s, an ethnic conception of German nationality, accepting migrants only as temporary “guest workers” on the grounds that Germany was “not an immigrant country.” European nations took for granted the ethnic cohesion of their cultures and the necessity of barring the entry and incorporation of people from different cultures categorized as a threat to the “national character.”

Why, then, did the entire Western liberal establishment came to the view that European ethnocentrism was fundamentally at odds with liberal principles a few decades after WWII?

I argued in a paper posted at CEC over a month ago (which I have withdrawn because it was flawed) that a new set of norms (human rights, civic nationalism, race is a construct) with an in-built tendency for further radicalization suddenly came to take a firm hold over Western liberal nations in response to the Nazi experience, and that once these norms were accepted, and actions were taken to implement them institutionally, they came to “entrap” Westerners within a spiral that would push them into ever more radical policies that would eventually create a situation in which Western nations would come to be envisioned as places always intended to be progressing toward a future utopia in which multiple races would co-exist in a state of harmony.

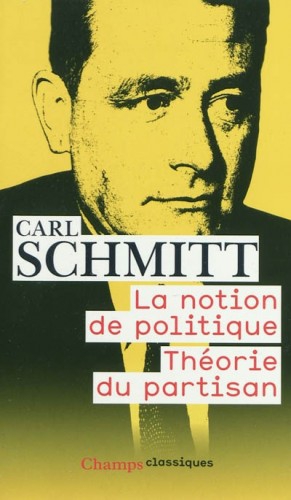

Carl Schmitt

Was there something within the racialist liberalism of the pre-WW II era that made it susceptible to the promulgation of these norms and their rapid radicalization thereafter? Why did Western leaders succumbed to the radicalization of these norms so easily? The answer may be found in Carl Schmitt’s argument [2] that liberal states lack a strong concept of the political. I take this to mean that liberals leaders have an inherent weakness as political beings due to their inability to think of their nation states as a collectivity of people laying sovereignty claim over a territory that distinguishes between friends and enemies, who can belong and who cannot belong in the territory. Liberals believe that their nation states are associations formed by individuals for the purpose of ensuring their natural right to life, liberty, and happiness. They have an imaginary view of their liberal states as associations created by isolated individuals reaching a covenant, a contract or agreement, amongst themselves in abstraction from any prior community. They have a predilection to whitewash the fact that their liberal states, like all states, were forcibly created by a people with a common language, heritage, racial characteristics, religious traditions, and a sense of territorial acquisition involving the derogation of out-groups.

For this reason, in the words of Carl Schmitt, liberals have an undeveloped sense of the political, an inability to think of themselves as members of a political entity that was created with a clear sense of who can belong and who cannot belong in the community. Having a concept of the political presupposes a people with a strong sense of who can be part of their political community, who can be friends of the community and who cannot be because they pose a threat to the existence and the norms of the community.

For this reason, in the words of Carl Schmitt, liberals have an undeveloped sense of the political, an inability to think of themselves as members of a political entity that was created with a clear sense of who can belong and who cannot belong in the community. Having a concept of the political presupposes a people with a strong sense of who can be part of their political community, who can be friends of the community and who cannot be because they pose a threat to the existence and the norms of the community.

Liberals tend to deny that man is by nature a social animal, a member of a collective. They think that humans are all alike as individuals in wanting states that afford them with the legal framework that individuals need in the pursuit of liberty and happiness. They hold a conception of human nature according to which humans can avoid deadly conflict through a liberal state which gives everyone the possibility to improve themselves and society through market competition, technological innovation, and humanitarian works, creating an atmosphere in which political differences can be resolved through peaceful consensus by way of open deliberation.

They don’t want to admit openly that all liberal states were created violently by a people with a sense of peoplehood laying sovereign rights over an exclusive territory against other people competing for the same territory. They don’t want to admit that the members of the competing outgroups are potential enemies rather than abstract individuals seeking a universal state that guarantees happiness and security for all regardless of racial and religious identity. Humans are social animals with a natural impulse to identify themselves collectively in terms of ethnic, cultural and racial markers. But today Europeans have wrongly attributed their unique inclination for states with liberal constitutions to non-Europeans. They have forgotten that liberal states were created by a particular people with a particular individualist heritage, beliefs, and religious orientations. They don’t realize that their individualist heritage was made possible within the context of states or territories acquired through force to the exclusion of competitors. They don’t realize that a liberal state if it is to remain liberal must act collectively against the inclusion of non-Europeans with their own in-group ambitions.

Hegel, Hobbes, and Schmitt

But I think that Schmitt should be complemented with Hegel’s appropriation of the ancient Greek concept of “spiritedness.” Our sense of honor comes from our status within our ethnocultural group in our struggle for survival and competition with other groups [4]. This is the source of what the ancient Greeks called “spiritedness,” that is a part of the soul comprising, in Plato’s philosophy, pride, indignation, shame, and the need for recognition. Plato believed that the human soul consisted of three parts:

- a physically desiring part that drives humans to seek to satisfy their appetites for food, comfort, and sensual pleasure;

- a reasoning part that allows humans to calculate the best way to get the things they desire; and

- a “spirited” part that drives humans to seek honor and renown amongst their people.

Liberal theory developed in reaction to the destructive tendency inbuilt into the spirited part which was exemplified with brutal intensity during the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) and English Civil War 1642-1651). Thomas Hobbes devalued the spirited part of man as just another appetite for power, for riches, and adulation. At the same time, he understood that this appetite was different from the mere natural appetites for food and sensual pleasure, in that they were insatiable and conflict-oriented.

State of nature according to Hobbes

Hobbes emphasized the destructive rather than the heroic character of this aspect of human nature. In the state of nature men are in constant competition with other men for riches and honor, and so enmity is a permanent condition of the state of nature, killing, subduing, and supplanting competitors. However, Hobbes believed that other aspects of human nature, namely, the instinct for self-preservation, fear of death and desire for “commodious living,” were more powerful passions among humans, and that it was these passions, the fear of death in particular, which eventually led men to agree to create a strong central authority that would end the war of competing megalomaniacs, and maintain the peace by monopolizing the means of violence and agreeing to ensure the secure pursuit of commodious living by all. The “insatiable desire and ambition of man” for power and adulation would henceforth be relegated to the international sphere.

But by the second half of the seventeenth century Hobbes’s extreme pessimism about human nature gradually gave way to more moderate accounts in which economic self interest in the market place, love of money, as calculated and contained by reason, would come to be seen as the main passion of humans. The ideal of the spirited hero striving for honor and glory was thoroughly demeaned if not denounced as foolish. By the eighteenth century money making was viewed less as avaricious or selfish and more as a peaceful passion that improves peoples’ manners and “makes for all the gentleness of life.” As Montesquieu worded it, “wherever there is commerce, there the ways of men are gentle.” Commerce, it was indeed anticipated, would soften the barbaric ways of human nature, their atavistic passions for glorious warfare, transforming competition into a peaceful endeavour conducted by reasonable men who stood to gain more from trade than the violent usurpation of other’s peoples property.

Eventually, liberals came to believe that commerce would, in the words expressed by the Scottish thinker William Robertson in 1769, “wear off those prejudices which maintain distinction and animosity between nations.” By the nineteenth century liberals were not as persuaded by Hobbes’s view that the state of nature would continue permanently in the international relationships between nations. They replaced his pessimistic argument about human nature with a progressive optimism about how humans could be socialized to overcome their turbulent passions and aggressive instincts as they were softened through affluence and greater economic opportunities. With continuous improvements in the standard of living, technology and social organization, there would be no conflicts that could not be resolved through peaceful deliberation and political compromise.

Eventually, liberals came to believe that commerce would, in the words expressed by the Scottish thinker William Robertson in 1769, “wear off those prejudices which maintain distinction and animosity between nations.” By the nineteenth century liberals were not as persuaded by Hobbes’s view that the state of nature would continue permanently in the international relationships between nations. They replaced his pessimistic argument about human nature with a progressive optimism about how humans could be socialized to overcome their turbulent passions and aggressive instincts as they were softened through affluence and greater economic opportunities. With continuous improvements in the standard of living, technology and social organization, there would be no conflicts that could not be resolved through peaceful deliberation and political compromise.

The result of this new image of man and political relations, according to Schmitt, was a failure on the part of liberal nations to understand that what makes a community viable as a political association with sovereign control over a territory is its ability to distinguish between friends and enemies, which is based on the ability to grasp the permanent reality that Hobbes understood about the nature of man, which is that humans (the ones with the strongest passions) have an insatiable craving for power, a passion that can be held in check inside a nation state with a strong Leviathan ruler, but which remains a reality in the relationship between nations. But, whereas for Hobbes the state of nature is a war between individuals; for Schmitt one can speak of a state of war between nations as well as between groups within a nation. Friends and enemies are always groupings of people. In our time of mass multicultural immigration we can see clearly how enemy groups can be formed inside a national collectivity, groups seeking to undermine the values and the ethnic character of the national group. Therefore, to have a concept of the political is to be aware, in our multicultural age, of the possibility that enemy outgroups can emerge within our liberal nations states; it is to be aware that not all humans are equally individualistic, but far more ethnocentric than Europeans, and that a polity which welcomes millions of individuals from collectivist cultures, with a human nature driven by the passions for power and for recognition, constitute a very dangerous situation.

It was Hegel, rather than Hobbes, who spoke of the pursuit of honor instead of the pursuit of riches or power for its own sake, as the spirited part of human nature, which is about seeking recognition from others, a deeply felt desire among men to be conferred rightful honor by their peers. We can bring this Hegelian insight into Schmitt to argue that the spirited part of the soul is intimately tied to one’s sense of belonging to a political community with ethno-cultural markers. Without this spirited part members of a community eventually lose their sense of collective pride, honor, and will to survive as a political people. It is important to understand that honor is all about concern for one’s reputation within the context of a group. It is a matter of honor for immigrants, the males in the group, to affirm their heritage regardless of how successful they may be economically. Immigrants arriving in large numbers are naturally inclined to establish their own ethnic groupings within Western nations rather than disaggregate into individual units, contrary to what liberal theory says.

Non-White ethnic groupings stand as “the other,” “the stranger,” to use Schmitt’s words, in relation to nations where Europeans still constitute the majority. The friend-enemy distinction, certainly “the Us versus Them” distinction, can be applied to the relation between non-White ethnic groupings and European national groupings in the degree to which the collective actions of non-European groups negates the heritage and overall way of life of the majority European population. Ethnic groupings that negate the way of life of European liberal nations must be repulsed if European nations are to preserve their “own form of existence.” To be cognizant of this reality is what it means to have a concept of the political in our current age of mass immigration. It does not mean that alien groupings are posing an immediate physical threat. Enemy groupings may also emerge as a major force through sheer demographic growth in a seemingly peaceful atmosphere, leading to all sorts of differences over voting patterns, accumulation of wealth and resources, ethnic hierarchies, divergent customs and religious practices, that become so pervasive that they come to threaten the way of life of the founding peoples, polarizing the nation into US versus Them.

The Leftist Interpretation of Schmitt is Wrong

But don’t Western liberals have enemies? Don’t they believe, at least many Republicans, that Islamic radicals, and nations openly opposed to “Western values,” are enemies of liberalism, against whom military violence may be used when necessary, even if Republicans negate the political in the sense that they want to bring about a situation in which humans define themselves as economic agents, or as moral crusaders dedicated to “democratic” causes? Don’t multicultural liberals believe that opponents of multiculturalism and mass immigration in Western countries are “deplorable” people who must be totally marginalized as enemies of humanity?

Academics on the left have indeed appropriated Schmitt to argue that right wing liberals have not negated the political but simply produced a highly effective smokescream over the West’s ambition to impose an American-led corporate order in the world nicely wrapped with human rights for everyone. They see Schmitt as someone who can teach us how to remove the smokescream of “democracy,” “human rights,” and “economic liberty” from Western hegemony, exposing the true power-seeking intentions behind the corporate liberal elites.

It seems to me that this appropriation of Schmitt is seriously flawed. Of course, Schmitt did not say that liberal nations as such are utterly devoid of any political existence, and of a concept of the political, since the very existence of a state supposes a sovereign right over a territory. A complete denial of the political would amount to a denial of the existence of one’s state. It is also true that for Schmitt “what has occurred [in liberal nations] is that economics has become political” in the enormous power that capitalist firms have, and in the way liberal states seek to augment, through non-economic means, their market share across the world. More than this, Schmitt emphasized how liberal states have “intensified” the enemy-friend distinction by ostracizing as enemies any state or political group disagreeing with their conception of humanity and conceptualizing liberal aggression against illiberal nations as final wars to end all wars.

There is no question, however, that Schmitt’s central thesis is that liberalism has no concept of the political and that it lacks a capacity to understand the friend-enemy distinction. Liberals believe that the “angelic” side of humans can manifest itself through proper liberal socialization, and that once individuals practice a politics of consensus-seeking and tolerance of differences, both inside their nations and in their relationships with other liberal nations, they will learn to avoid war and instead promote peaceful trade and cultural exchanges through commercial contracts, treaties, and diplomacy. Even though liberal states have not been able to “elude the political,” they have yet to develop theories of the political which apprehend this sphere of human life in terms of its defining aspect, the friend-enemy distinction. Rather, liberal theorists are inclined to think of the state as one pressure group among a plurality of political groups all of which lack a concept of the political in thinking that differences between groups can be handled through institutions that obtain consensus by means of neutral procedures and rational deliberation.

The negation of the political is necessarily implicit in the liberal notion that humans can be defined as individuals with natural rights. It is implicit in the liberal aspiration to create a world in which groups and nations interact through peaceful economic exchanges and consensual politics, and in which, accordingly, the enemy-friend distinction and the possibility of violence between groups is renounced. The negation of the political is implicit in the liberal notion of “humanity.” The goal of liberalism is to get rid of the political, to create societies in which humans see themselves as members of a human community dedicated to the pursuit of security, comfort and happiness. Therefore, we can argue with Schmitt that liberals have ceased to understand the political insomuch as liberal nations and liberal groups have renounced the friend-enemy distinction and the possibility of violence, under the assumption that human groups are not inherently dangerous to each other, but can be socialized gradually to become members of a friendly “humanity” which no longer values the honor of belonging to a group that affirms ethno-cultural existential differences. This is why Schmitt observes that liberal theorists lack a concept of the political, since the political presupposes a view of humans organized in groupings affirming themselves as “existentially different.”

The negation of the political is necessarily implicit in the liberal notion that humans can be defined as individuals with natural rights. It is implicit in the liberal aspiration to create a world in which groups and nations interact through peaceful economic exchanges and consensual politics, and in which, accordingly, the enemy-friend distinction and the possibility of violence between groups is renounced. The negation of the political is implicit in the liberal notion of “humanity.” The goal of liberalism is to get rid of the political, to create societies in which humans see themselves as members of a human community dedicated to the pursuit of security, comfort and happiness. Therefore, we can argue with Schmitt that liberals have ceased to understand the political insomuch as liberal nations and liberal groups have renounced the friend-enemy distinction and the possibility of violence, under the assumption that human groups are not inherently dangerous to each other, but can be socialized gradually to become members of a friendly “humanity” which no longer values the honor of belonging to a group that affirms ethno-cultural existential differences. This is why Schmitt observes that liberal theorists lack a concept of the political, since the political presupposes a view of humans organized in groupings affirming themselves as “existentially different.”

Thus, using Schmitt, we can argue that while Western liberal states had strong ethnic markers before WWII/1960s, with immigration policies excluding ethnic groupings deemed to be an existential threat to their “national character,” they were nevertheless highly susceptible to the enactment of norms promoting the idea of civic identity, renouncing the notion that races are real, romanticizing Third World peoples as liberators, and believing that all liberal rights should be extended to all humans regardless of nationality, because they lacked a concept of the political. The racial or ethnocentric liberalism that prevailed in the West, collectivist as it remained in this respect, was encased within a liberal worldview according to which, to use the words of Schmitt, “trade and industry, technological perfection, freedom, and rationalization . . . are essentially peaceful [and . . .] must necessarily replace the age of wars.”

They believed that their European societies were associations of individuals enjoying the right to life and liberty. The experience of WWII led liberals to the conclusion that the bourgeois revolutions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which had finished feudal militarism, and which then led the Allies to fight a world war against the new militarism of fascism, were still “unfinished revolutions.” The liberal bourgeois nations were still not liberal enough, in their division and ranking of individuals along ethnic lines, with many individuals not enjoying the same rights that were “naturally” theirs. The project of the Enlightenment, “the universalist spirit of the political Enlightenment,” in the words of Jürgen Habermas, was not yet completed.

What Western liberals in the 1960s, the ones who dismantled immigration laws that discriminated against non-Whites, and introduce the notion that multiple cultures could co-exist within the same state, did not realize was that their sense of racial identity was the one collectivist norm still holding their liberal nations safely under the concept of the political. Once this last bastion of collectivism was deconstructed, liberal nations would be caught up within a spiral of radicalization wherein liberal nations would find it ever more difficult to decide which racial groups may constitute a threat to their national character, and which groups may be already lurking within their nations ready to play the political with open reigns, ready to promote their own ethnic interests; in fact, ready to play up the universal language of liberalism, against ethnocentric Europeans, so as to promote their own collectivist interests.

Source: http://www.eurocanadian.ca/2016/10/carl-schmitt-liberal-n... [6]

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Par cet exemple simple, on comprend mieux le lien entre consommation, déracinement et individualisme. On comprend mieux aussi pourquoi on parlera de « fait anthropologique total ». Le rapport à l’Etat a aussi pour conséquence de renforcer l’individualisme : puisque l’État papa ou l’État maman est là (c.a.d : la version rassurante ou répressive de l’Etat), alors quel intérêt d’entretenir des liens de solidarité ? Nous sommes « seuls ensembles ». On devient un « sujet de l’Etat » et finalement tout le monde accepte tacitement le contrat : payer ses impôts pour avoir des « droits à » mais aussi le « droit de ». La loi prend la place de la coutume (locale) ou de la décence commune (pour replacer direct du Michéa).

Par cet exemple simple, on comprend mieux le lien entre consommation, déracinement et individualisme. On comprend mieux aussi pourquoi on parlera de « fait anthropologique total ». Le rapport à l’Etat a aussi pour conséquence de renforcer l’individualisme : puisque l’État papa ou l’État maman est là (c.a.d : la version rassurante ou répressive de l’Etat), alors quel intérêt d’entretenir des liens de solidarité ? Nous sommes « seuls ensembles ». On devient un « sujet de l’Etat » et finalement tout le monde accepte tacitement le contrat : payer ses impôts pour avoir des « droits à » mais aussi le « droit de ». La loi prend la place de la coutume (locale) ou de la décence commune (pour replacer direct du Michéa). Autre élément qu’on pourrait citer dans la décolonisation de l’imaginaire : le rapport au temps. Une des mutations anthropologique majeure induite par le progrès technique, c’est le changement de notre rapport au temps. On ne peut aller plus vite que le cheval que depuis la fin du XIXeme siècle. La « société de la vitesse » a donc émergée et aucun régime, y compris les régimes qui voulaient lutter contre l’homme libéral, n’a été contre la société de la vitesse. Il est nécessaire qu’il y ait une part prométhéenne mais on n’en maîtrise pas toujours les conséquences. La vitesse, si elle a contribué à la « grandeur des nations », a aussi favorisé une philosophie puis une pratique néo-nomadiste. Le déplacement fait parti de notre façon d’habiter le territoire. J’y reviendrai en troisième partie. Il faudrait donc repenser notre rapport au temps, prendre le temps, faire moins de « choses » mais mieux : la « philosophie de l’escargot » des décroissants.

Autre élément qu’on pourrait citer dans la décolonisation de l’imaginaire : le rapport au temps. Une des mutations anthropologique majeure induite par le progrès technique, c’est le changement de notre rapport au temps. On ne peut aller plus vite que le cheval que depuis la fin du XIXeme siècle. La « société de la vitesse » a donc émergée et aucun régime, y compris les régimes qui voulaient lutter contre l’homme libéral, n’a été contre la société de la vitesse. Il est nécessaire qu’il y ait une part prométhéenne mais on n’en maîtrise pas toujours les conséquences. La vitesse, si elle a contribué à la « grandeur des nations », a aussi favorisé une philosophie puis une pratique néo-nomadiste. Le déplacement fait parti de notre façon d’habiter le territoire. J’y reviendrai en troisième partie. Il faudrait donc repenser notre rapport au temps, prendre le temps, faire moins de « choses » mais mieux : la « philosophie de l’escargot » des décroissants.