We must change back to the vision of the living cosmos; we must.

The oldest Pan is in us, and he will not be denied.

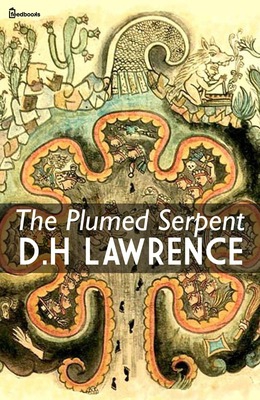

The Plumed Serpent is the story of an Aztec pagan revolution that spreads through Mexico during the time of the Mexican Revolution (the 1910s). Published in 1926, it also has themes of anti-capitalism, anti-Americanism, romanticism, nationalism, and primal and traditional roles for men and women.

The protagonist is 40-year-old Kate Leslie, the widow of an Irish revolutionary. She’s not particularly close to her grown children from her first husband, and seeking solitude and change in the midst of her grief she settles temporarily in Mexico.

Soon she meets Don Ramón Carrasco, an intellectual who’s attempting to rid the country of Christianity and capitalism and replace them with the cult of the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl (“the plumed serpent”) and Mexican nationalism. He’s assisted in his vision by Don Cipriano Viedma, a general in the Mexican army. Ramón provides the leadership, poetry, and propaganda that helps the movement take off, and Cipriano lends a military counterpoint.

Ramón writes hymns, then distributes copies to the villagers who quickly become fascinated by the idea of the old gods returning to Mexico:

Your gods are ready to return to you. Quetzalcoatl and Tlaloc, the old gods, are minded to come back to you. Be quiet, don’t let them find you crying and complaining. I have come from out of the lake to tell you the gods are coming back to Mexico, they are ready to return to their own home.

The Mexican commoners flock to listen as hymns are read (Mexico’s illiteracy rate was about 78 percent in 1910) (Presley). Soon the villagers are inspired to dance and drum in the native trance-inducing style that’s foreign to Christian worship, and they refuse the Church’s orders to quit listening to the Hymns of Quetzalcoatl. According to Smith, Lawrence was “interested in two related concepts of male homosociality: Männerbund and Blutbrüdershaft,” and there certainly are aspects of this in The Plumed Serpent among the Men of Quetzalcoatl. Ramón also employs an array of craftsmen to create the aesthetics for the Quetzalcoatl movement—ceremonial costumes, the Quetzalcoatl symbol in iron, and traditional Indian dress that’s adopted by the male followers.

Orchestrating a Pagan Revolution

The Plumed Serpent has been called D. H. Lawrence’s “most politically controversial novel” (Krockel). Despite its fascinating plot and the brilliant prose readers expect from Lawrence, it’s been called every name modernists can sling at a book—fascist, sexist, racist, silly, offensive, propaganda, difficult, an embarrassment. So many people have slammed the novel that when literary critic Leslie Fiedler said Lawrence had no followers—at a D.H. Lawrence festival, no less—William S. Burroughs interrupted to say how influenced he was by The Plumed Serpent (Morgan).

A primary reason Lawrence’s book is criticized is because his vision for Mexico may have been inspired by a trip to the Weimar Republic in the 1920s, after which he spoke positively of the growing völkisch movement and its focus on pagan traditions, saying in a 1924 letter: “The ancient spirit of pre-historic Germany [is] coming back, at the end of history” (Krockel). This is a misguided view because the Quetzalcoatl movement has none of the vitriol and racism that later characterized National Socialism (a Christianity ideology). Instead, the Quetzalcoatl leaders’ plan is to unite the various ethnicities in Mexico into one pagan culture, and whites living in the country will be allowed to stay if they are peaceful.

In The Plumed Serpent, Ramón speaks of the need for every country to have its own Savior, and his vision for a traditional, anti-capitalistic society includes a rebirth of paganism for the entire world:

If I want Mexicans to learn the name of Quetzalcoatl, it is because I want them to speak with the tongues of their own blood. I wish the Teutonic world would once more think in terms of Thor and Wotan, and the tree Igdrasil. And I wish the Druidic world would see, honestly, that in the mistletoe is their mystery, and that they themselves are the Tuatha De Danaan, alive, but submerged. And a new Hermes should come back to the Mediterranean, and a new Ashtaroth to Tunis; and Mithras again to Persia, and Brahma unbroken to India, and the oldest of dragons to China.

Although Lawrence’s novel has been criticized numerous times for post-colonial themes, such is an intellectually lazy and incomplete reading. According to Oh, “What Lawrence tries to do in The Plumed Serpent is the reverse of colonialist eradication of indigenous religion. The restoration of ancient Mexican religion necessarily accompanies Lawrence’s critiques of Western colonial projects.”

Lawrence and Nietzsche: A Philosophy of the Future

Ramón performs public invocations to the Aztec god and plans to proclaim himself the living Quetzalcoatl. (When the time is right, his friend Cipriano will be declared the living warrior god Huitzilopochtli, and Kate is offered a place in the pantheon as the goddess Malintzi.) But Ramón’s wife is a devout Catholic and fervently tries to convince him to stop the pagan revolution. Nietzsche was a major influence on Lawrence by the 1920s, and Ramón’s harsh diatribe to his Christian wife sounds straight out of The Genealogy of Morals:

But believe me, if the real Christ has not been able to save Mexico—and He hasn’t—then I am sure the white Anti-Christ of charity, and socialism, and politics, and reform, will only succeed in finally destroying her. That, and that alone, makes me take my stand.—You, Carlota, with your charity works and your pity: and men like Benito Juarez, with their Reform and their Liberty: and the rest of the benevolent people, politicians and socialists and so forth, surcharged with pity for living men, in their mouths, but really with hate . . .

The Plumed Serpent has been compared to Thus Spoke Zarathustra as well. Both feature religious reformers intent on creating the Overman, both use pre-Christian deities in their mythos, and both proclaim that God is dead (Humma). (In a priceless scene, Ramón has Christ and the Virgin Mary retire from Mexico while he implores the villagers to call out to them, “Adiós! Say Adiós! my children.”) A brutal overturning of Christian morality is present in both narratives. In addition, Ramón teaches his people to become better than they are, to awaken the Star within them and become complete men and women.

The Plumed Serpent is an engaging handbook for initiating a pagan revival in the West. The methods employed by Ramón would be more effective in a rural society 100 years ago, but readers will likely find inspiration in the Quetzalcoatl movement’s aesthetics and success. It’s an immensely enjoyable read for anyone interested in reconstructionist paganism or radical traditionalism.

Endnotes:

Humma, John B. Metaphor and Meaning in D.H. Lawrence’s Later Novels. University of Missouri (1990).

Krockel, Carl. D.H. Lawrence and Germany: The Politics of Influence. Editions Rodopi BV (2007).

Morgan, Ted. Literary Outlaw: The Life and Times of William S. Burroughs. W. W. Norton (2012).

Oh, Eunyoung. D.H. Lawrence’s Border Crossing: Colonialism in His Travel Writing and Leadership Novels. Routledge (2014).

Presley, James. “Mexican Views on Rural Education, 1900-1910.” The Americas, Vol. 20, No. 1 (July 1963), pp. 64-71.

Smith, Jad. “Völkisch Organicism and the Use of Primitivism in Lawrence’s The Plumed Serpent.” D.H. Lawrence Review, 30:3. (2002)

For more posts on radical traditionalism and Julius Evola, please visit the archives here.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg