jeudi, 05 mars 2020

Karl Haushofer and the Rise of the Monsoon Countries

Karl Haushofer and the Rise of the Monsoon Countries

This writer understood geopolitical potential of the Indo-Pacific decades ago.

Long before Robert Kaplan identified the Indian Ocean and its surrounding region as the new geopolitical pivot of world politics in his 2010 book Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power, the leading intellectual theorist of German geopolitics in the 1920s and 30s, Karl Haushofer, foresaw the power potential of what he called the “Indo-Pacific” or “Asiatic Monsoon countries” and urged German policymakers to promote the geopolitical unity of this region to offset British and American sea power.

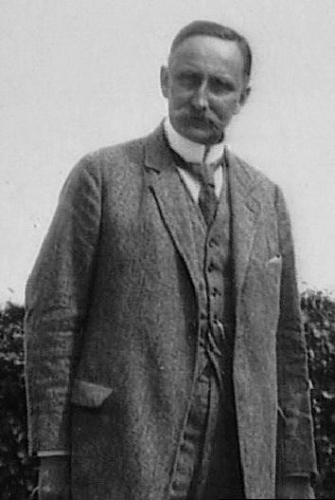

Born in Munich on the eve of the Franco-Prussian War, Haushofer studied at the Royal Maximilian Gymnasium before joining the Bavarian Army in 1887. He excelled at the Military Academy (Kriegsschule), attended artillery and engineering school, and from 1895 to 1898 studied at the General Staff College (Kriegsakademie). Between 1898 and 1908, Haushofer served with the troops at various posts, taught military history at the Military Academy, and worked on the General Staff.

In 1908, Major Haushofer was assigned to the German Embassy in Tokyo to observe and study the Japanese military that had so recently stunned the world by besting the great Russian Empire in the Russo-Japanese War. On his way there, he stopped at Cyprus, Alexandria, Aden, India, Singapore and elsewhere and noticed the Union Jack flying from those strategic outposts. Haushofer’s trip to the Orient shaped all of his subsequent geopolitical writing. As Andreas Dorpalen noted in The World of General Haushofer, it was in Japan and the Far East that his “transformation from political geographer to geopolitican was completed.”

Haushofer studied the geopolitical works of Friedrich Ratzel, Rudolf Kjellen, and Sir Halford Mackinder, calling Mackinder’s 1904 “The Geographical Pivot of History” the greatest of all geographical world views. Like Ratzel and Kjellen, Haushofer believed that nation-states were living organisms that either expanded or declined and eventually died. He included factors such as location, size, population, national unity, and economics in his analyses of the power potential of nations. Haushofer wrote his Ph.D thesis in 1911 on the geographic foundations of Japan’s power. Between 1913 and 1923 – with a gap for his service in the First World War – he wrote five more books on Japan and the Far East. Then, in 1924, he wrote his most important geopolitical work, The Geopolitics of the Pacific Ocean. In that book and in articles written for Geographische Zeitschrift and Zeitschrift fur Geopolitik, Haushofer urged German leaders to align their country to the Indo-Pacific peoples of India, China and Japan.

He described the Monsoon countries as “[e]xtending from the mouth of the Indus to that of the Amur and taking in the littoral of Southeast Asia as well as the divides of the large central highland of Asia.” With the “uniform climate rhythm” of the monsoon, more than half the world’s population, and age-old Indian and East Asian cultures, the region contains “the two greatest concentrations of mankind ever witnessed in the history of the world.” Those countries, wrote Haushofer, “are beginning to stir and to rise.”

Haushofer later criticized Japan for its invasion of China in the 1930s, predicting that it would over-extend itself and suffer defeat. He opposed Germany’s invasion of Soviet Russia in June 1941 for the same reason. Haushofer hoped instead for a great transcontinental Eurasiatic bloc to oppose the sea powers of Britain and the United States, with Japan leading the Asian sphere and Germany leading the European sphere and both powers collaborating with Russia. In this, he underestimated the powerful force of nationalism and political rivalries on the world stage.

Haushofer and his geopolitical ideas were tarnished by his associations with key Nazi leaders, including Rudolph Hess. Some scholars have attempted to blame him for creating a geopolitical blueprint for Nazi expansion. There is no convincing evidence, however, that he was ever an adviser to Hitler or had any significant influence on Nazi foreign policy. Indeed, as noted above, Haushofer was vigorously opposed to the German invasion of Soviet Russia that was the centerpiece of Hitler’s expansionist policies. Both Haushofer and his son Albrecht wound up in concentration camps. Albrecht was later shot for his alleged involvement in a plot to kill Hitler, and Karl Haushofer and his wife committed suicide after the war. Haushofer was interrogated after the war by Fr. Edmund Walsh of Georgetown University who determined that there was no evidence to prosecute him for war crimes.

Haushofer’s tarnished reputation should not prevent statesmen and scholars from perusing his works, especially those focused on the Indo-Pacific region. The monsoon countries, especially China and India, are rising just as he predicted more than ninety years ago. That region has become the focal point of global geopolitics in the 21st century. Skeptics should consider this quote from a 1939 article: “If an empire could arise with Japan’s soul in China’s body, that would be a power which would put even the empires of Russia and the United States in the shade.”

Francis P. Sempa is the author of Geopolitics: From the Cold War to the 21st Century (Transaction Books) and America’s Global Role: Essays and Reviews on National Security, Geopolitics, and War (University Press of America). He has written articles and reviews on historical and foreign policy topics for Strategic Review, American Diplomacy, Joint Force Quarterly, the University Bookman, the Washington Times, the Claremont Review of Books, and other publications. He is an adjunct professor of political science at Wilkes University, and a contributing editor to American Diplomacy.

00:50 Publié dans Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : karl haushofer, géopolitique, océan indien, mousson, zone de la mousson |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les commentaires sont fermés.