Par Moon of Alabama

Si vous vous demandez ce qui se passe au Myanmar, regardez simplement ces cartes.

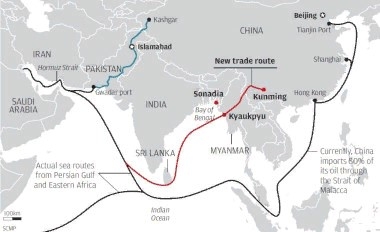

La Chine a besoin de pétrole mais sa principale voie d’approvisionnement maritime, qui passe par le détroit de Malacca, est vulnérable.

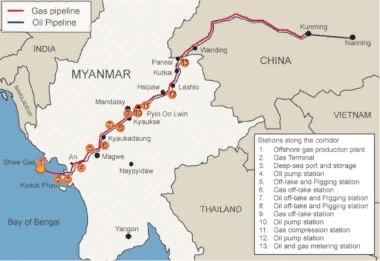

Des oléoducs passant par le Pakistan et le Myanmar offrent des voies alternatives.

Les pipelines, les routes et les lignes ferroviaires qui traversent le Myanmar ne sont pas seulement dans l’intérêt de la Chine, mais aussi une grande chance pour le Myanmar de se développer. Tout cela est bon pour son intérêt national.

Les États-Unis et leurs alliés sont hostiles à la Chine. Menacer de couper ses approvisionnements en pétrole est probablement l’outil le plus puissant dont ils disposent. Du coup, toute voie d’approvisionnement alternative pour la Chine rend cet outil moins puissant. L’idée est donc d’empêcher l’utilisation éventuelle de ces routes.

Depuis sa fondation après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, le Myanmar a été dirigé, plus ou moins brutalement, par ses militaires anticolonialistes.

Le premier plan des États-Unis pour prendre le contrôle du Myanmar consista à installer un « gouvernement démocratique » qui se plierait à leurs exigences. En 2010, sous la pression des révolutions de couleur fomentées par les États-Unis, les militaires ont autorisé un gouvernement civil mais ont conservé une grande partie de leur pouvoir constitutionnel et économique. En 2016, la candidate préférée des États-Unis, Suu Kyi, la fille de l’ancien chef militaire et père de la nation, Aung San, a été installée à la tête d’un nouveau gouvernement.

Mais Aung San Suu Kyi s’est révélée être une nationaliste et a rapidement perdu de son utilité aux yeux des « changeurs de régime » américains. Elle était aussi amie avec la Chine que les militaires et se montrait tout aussi agressive envers les nombreuses minorités ethniques du Myanmar. Ce n’est donc pas sur ces sujets qu’elle s’est finalement brouillée avec les militaires. L’armée possède des industries clés au Myanmar et Aung San Suu Kyi, ainsi que les personnes de la « société civile » qui la soutiennent, voulaient avoir leur part.

Les élections de 2020, qui ont exclu du vote de nombreuses régions ethniques, ont apporté un soutien écrasant à Aung San Suu Kyi. Cela a alarmé les militaires, qui se sont mis à craindre que leur principale source de revenus ne soit bientôt menacée. Le 1er février, ils ont lancé un coup d’État et placé Aung San Suu Kyi en résidence surveillée.

Les États-Unis ont alors eu une nouvelle occasion d’intervenir. Ils ont immédiatement réactivé les 77 organisations de la « société civile » du Myanmar qu’ils financent par l’intermédiaire de la National Endowment for Democracy, une émanation de la CIA. Des manifestations ont été lancées en même temps que des attaques contre des entreprises et des biens chinois.

Comme je l’ai décrit à l’époque :

Il s'agit donc manifestement d'une tentative de révolution de couleur dirigée

contre l'armée.

Ce qui est intriguant, c'est la vitesse à laquelle elle a démarré. Les révolutions

de couleur nécessitent généralement des années pour constituer des groupes

et préparer des dirigeants. Elles ont besoin d'un soutien financier et de

communication, ainsi que d'orientations politiques de la part de "conseillers"

venant d’ambassades "occidentales". Celle-là, il n'a fallu que dix jours pour

la lancer.

En 2005, l'administration Bush entretenait la "société civile" du Myanmar et

Suu Kyi, qui était alors en résidence surveillée. Elle est apparue lors de la

"révolution de couleur safran" en 2007 et lors du cyclone Nargis en 2008,

lorsque l'administration Bush a tenté d'utiliser l’absurde responsabilité de

protéger (R2P) pour mettre une botte militaire sur le terrain.

Mais tout cela remonte à loin et, après l'arrivée au pouvoir de Suu Kyi,

il n'était plus nécessaire de poursuivre ces efforts.

D'ailleurs, en vertu de la constitution du Myanmar de 2008, les militaires

étaient toujours effectivement aux commandes. Avec la large victoire de

Suu Kyi aux dernières élections, il se pourrait qu'une tentative "occidentale",

planifiée de longue date, soit en cours pour enfin déloger les militaires de

leur position privilégiée et sortir le pays de l'orbite de la Chine.

Mais les chances que cela se produise un jour sont pratiquement nulles.

Environ 70 % de la population du Myanmar vit dans des zones rurales.

Les manifestations ne se produisent que dans les trois grandes villes,

Yangon, Mandalay et Naypyitaw, et sont relativement peu nombreuses.

Les militaires sont impitoyables et n'auront aucun mal à faire tomber les

manifestants.

Celui qui a lancé cette absurdité devrait être tenu responsable de la mise

en danger de ces personnes.

Comme je l’avais prédit, les manifestations et les grèves que le système

de révolution de couleur a lancées, sous la forme d’un mouvement de

désobéissance civile (MDC), se sont éteintes depuis :

Bien que Thiha ne veuille pas abandonner le MDC, il ne veut pas non plus

perdre son emploi à cause d’un contexte économique difficile. Après

avoir réfléchi pendant quelques jours, il a décidé de reprendre le travail.

"J'ai un prêt fait auprès d'une société de microfinancement que je dois

rembourser et une famille à soutenir - une femme et une fille de cinq ans",

a-t-il déclaré. "Il ne serait pas facile pour moi de trouver un autre emploi,

d'autant plus que je devrais changer de carrière".

Il n'y avait qu'une poignée d'employés présents lorsqu'il a repris le travail,

le 20 avril, mais leur nombre a augmenté chaque jour ; à la date limite du

29 avril, environ 80 % d'entre eux étaient revenus, même s'ils ne portaient

pas encore leur uniforme KBZ.

C'est une scène qui se répète dans tout le pays, alors que des dizaines

de milliers d’employés de banque en grève reprennent lentement le travail.

Cette tentative de révolution de couleur induite par les États-Unis

contre le coup d’État militaire a échoué.

Il est maintenant temps de passer au plan B, sur le modèle syrien :

« Si nous ne pouvons pas le soumettre, nous le détruirons ! »

Un important groupe rebelle ethnique birman a affirmé avoir abattu un

hélicoptère appartenant à l'armée du pays. Cet incident survient dans un

contexte de continuelles manifestations contre le récent coup d'État qui a

évincé le gouvernement civil du Myanmar.

L'Armée de l'indépendance de Kachin (KIA) a déclaré que l'hélicoptère avait

été abattu lundi dans la province de Kachin, située à l'extrême nord du

Myanmar. L'appareil aurait été détruit alors que l'armée du Myanmar effectuait

des frappes aériennes contre les rebelles. ...

Des images circulant en ligne montrent l'hélicoptère - probablement un Mi-17

de transport-assaut - apparemment touché par un lanceur de missiles

anti-aériens portable.

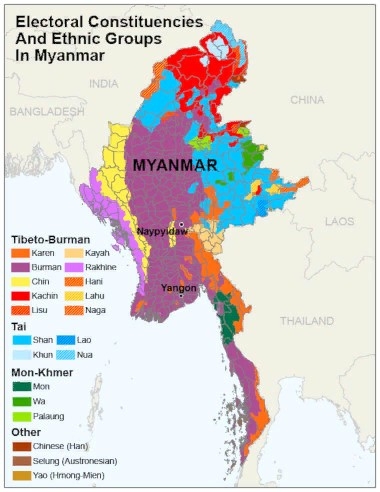

Les Kachins (en rouge), au nord-est, et les Karens (en orange), au sud-est, luttent depuis longtemps contre la majorité birmane (en violet foncé) et pour leur autonomie au sein du Myanmar. Pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, l’armée nationale birmane dirigée par Aung San a combattu aux côtés du Japon pour chasser la puissance coloniale britannique de Birmanie. La Grande-Bretagne, qui contrôlait également l’Inde à cette époque, a utilisé les Kachins et les Karens pour mener une guérilla contre les forces birmanes proxy du Japon.

Dans le cadre du projet Quad de lutte contre la Chine, ces anciens liens ont été réactivés. L’ancien ambassadeur indien, M.K. Bhadrakumar, explique ce plan :

Parallèlement, le MI6 britannique a cherché à réunir les principaux groupes de

guérilla séparatistes ethniques du Myanmar, les encourageant à profiter du

chaos pour ouvrir un second front.

En effet, une certaine proximité s'est développée depuis lors entre les

manifestants birmans de Yangon et de Mandalay d'une part et les groupes

ethniques minoritaires non birmans d'autre part. Malgré une histoire

d'antipathie mutuelle, leurs intérêts convergent aujourd'hui pour saigner

les militaires. C'est une coalition improbable de bouddhistes et de chrétiens,

mais comme l'évalue prudemment un analyste américain, c'est faisable : ...

Quoi qu'il en soit, à la mi-avril, la première attaque armée majeure contre

l'armée a été menée par l'Union nationale karen, le plus ancien groupe rebelle

du Myanmar (créé à l'origine par la puissance coloniale britannique pour

lui servir de force proxy).

Aujourd'hui, le gouvernement dit d'unité nationale a annoncé son intention

de créer une armée d'union fédérale - une force militaire composée de

transfuges des forces de sécurité, de groupes ethniques rebelles et de

volontaires. Ce serait un tournant qui transformerait l'agitation anti-militaire

en une confrontation armée contre les militaires. Le Myanmar entre dans

la phase cruciale où se trouvait la Syrie en 2011.

Le missile Man Portable Air Defense (Manpad) utilisé par les Kachin contre

un hélicoptère de l’armée du Myanmar n’est pas sorti de nulle part.

Il doit provenir du MI6 ou de la CIA, via les frontières largement ouvertes entre le Myanmar et l’Inde, pays membre du Quad. (Il est probablement plus compliqué d’obtenir des provisions pour les Karens près de la frontière thaïlandaise, car l’armée thaïlandaise est elle-même soumise à la pression d’une révolution de couleur américaine et n’aimerait pas contribuer à de tels efforts).

Il existe d’autres groupes ethniques des deux côtés de la frontière indienne qui peuvent être et seront utilisés pour mener une guérilla contre l’armée du Myanmar. Disposant gratuitement d’armes modernes, ils peuvent créer des dégâts considérables.

Pendant ce temps, un « gouvernement d’unité nationale » en exil, du genre de celui de Juan Guaido, sera utilisé pour faire croire qu’il existe une réelle opposition au gouvernement militaire. L’« armée d’union fédérale » sera une copie de l’« armée nationale syrienne » – un assemblage perdu de mercenaires et de divers groupes de seigneurs de guerre. Une organisation de propagande du type des « Casques blancs » devrait également faire son apparition prochainement.

L’objectif est de déclencher une vaste guerre civile qui rendra impossible la mise en œuvre de tout projet chinois au Myanmar.

Bhadrakumar constate que le projet est bien coordonné :

Le secrétaire d'État américain Antony Blinken s'est entretenu avec son

homologue indien S.Jaishankar pas moins de trois fois en autant de mois

depuis la prise du pouvoir par les militaires au Myanmar. Il est certain que

la coopération de l'Inde est cruciale pour le succès de l'entreprise

anglo-américaine au Myanmar.

Le Myanmar a occupé une place importante lors de la réunion des

ministres des affaires étrangères du G7 à Londres du 3 au 5 mai.

Jaishankar s'est rendu à Londres et a rencontré Blinken. Aucune

des deux parties n'a divulgué de détails, mais un rapport de

Deutsche-Welle a signalé que "la Chine était en tête de l'ordre du

jour alors que les ministres des affaires étrangères du G7 discutaient

d'une série de questions relatives aux droits de l'homme. La question

du coup d'État au Myanmar et de l'agression russe était également

à l'ordre du jour".

Le communiqué ajoute que les ministres du G7 ont regardé une vidéo

du gouvernement d'unité nationale du Myanmar afin "d'informer les

ministres de la situation actuelle sur le terrain". Le communiqué conjoint

publié à l'issue de la réunion de Londres consacre une grande attention

au Myanmar (paragraphes 21 à 24). Il exprime sa "solidarité" avec le

gouvernement d'unité nationale et appelle à des sanctions globales

contre l'armée du Myanmar, y compris un embargo sur les armes.

Les douleurs de naissance des insurrections ne sont jamais exposées au

public, car les agences de renseignement mettraient les acteurs en jeu.

La situation au Myanmar a atteint ce stade. C'est la première grande action

du Royaume-Uni post-Brexit ("Global Britain") sur la scène mondiale.

Comme souvent dans l'histoire moderne, Londres mènera la danse

depuis l'arrière.

Les contre-mouvements aux plans américains et britanniques viendront de Russie et de Chine. Une semaine avant le coup d’État, le ministre russe de la Défense, Sergei Shoigu, s’est rendu au Myanmar. Le 27 mars, le vice-ministre russe de la défense, Alexander Fomin, était présent lors du défilé annuel de la Journée des forces armées à Naypyidaw.

La Russie a des intérêts pétroliers au Myanmar et vend des armes à son armée. Elle empêche toute mesure contre le Myanmar au Conseil de sécurité des Nations unies. Signe qu’elle connaît les enjeux, elle a prévenu que des sanctions contre l’armée pourraient conduire à une véritable guerre civile.

Jusqu’à présent, la Chine est restée silencieuse sur cette question. Elle s’efforcera de garder un profil bas. Une intervention ouverte de la Chine est hors de question, mais l’aide chinoise pourrait devenir importante si ou quand le gouvernement du Myanmar subit des pressions financières.

Il est dit qu’un autre petit pays, qui ne demande qu’à être laissé tranquille, sera bientôt détruit par la tentative « occidentale » de maintenir la Chine à terre. Une guerre par procuration entre grandes puissances dont personne, à part des personnes déjà riches, ne profitera.

Moon of Alabama

Traduit par Wayan, relu par Hervé pour le Saker Francophone

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Par ailleurs, le contexte chinois est celui d'une culture dans laquelle l'école légaliste a agi en profondeur. Courant philosophique fondé au IIIe siècle avant J.-C. par Han Fei qui, en opposition aux idées confucéennes de bienveillance, de vertu et de respect des rituels, prêchait le droit du prince à exercer un pouvoir absolu et incontesté. Seule source du droit, le prince légaliste ne délègue aucune autorité à qui que ce soit. A côté de lui, il n'y a que des exécuteurs testamentaires, aux tâches strictement délimitées. En-dessous d'eux se trouvent les sujets, obligés seulement d'obéir.

Par ailleurs, le contexte chinois est celui d'une culture dans laquelle l'école légaliste a agi en profondeur. Courant philosophique fondé au IIIe siècle avant J.-C. par Han Fei qui, en opposition aux idées confucéennes de bienveillance, de vertu et de respect des rituels, prêchait le droit du prince à exercer un pouvoir absolu et incontesté. Seule source du droit, le prince légaliste ne délègue aucune autorité à qui que ce soit. A côté de lui, il n'y a que des exécuteurs testamentaires, aux tâches strictement délimitées. En-dessous d'eux se trouvent les sujets, obligés seulement d'obéir. Xi Jinping a redéfini le centre de gravité idéologique du parti communiste, redéfini la tolérance limitée de la dissidence, laquelle pouvait parfois se manifester mais a désormais disparu, de même toute forme d'autonomie, qui aurait pu être accordée au Xinjiang, à la Mongolie intérieure et à Hong Kong, a été supprimée.

Xi Jinping a redéfini le centre de gravité idéologique du parti communiste, redéfini la tolérance limitée de la dissidence, laquelle pouvait parfois se manifester mais a désormais disparu, de même toute forme d'autonomie, qui aurait pu être accordée au Xinjiang, à la Mongolie intérieure et à Hong Kong, a été supprimée.