samedi, 14 février 2015

Can Syria’s Cultural Heritage be a Fulcrum for Ending its Civil War?

Can Syria’s Cultural Heritage be a Fulcrum for Ending its Civil War?

For visitors to Syria these days, certainly this one, it’s almost become a cliche to shake ones head and mumble, “this is not your normal civil war.” Meaning that in spite of the dangerous environment for families and enormous sacrifices being paid daily, the Syrian people go about their lives with amazing resilience.

Yesterday, 2/5/15, was the latest example. Rebel mortars started raining on downtown at 7 a.m. after a rebel commander Zahran Alloush of the “Islam Army” tweeted that his forces would keep firing mortars and rockets “until the capital is cleansed.” An estimated nine people were killed, and dozens wounded in downtown Damascus from roughly 60 rebel mortars. By the end of the day more than seventy, most of them rebel forces, died as the Syrian army and rebel fighters trading salvos of rockets and mortar bombs.

Despite the bombardment, most office workers showed up for work, students arrived for classes at Damascus University, and the public schools were open although many were dismissed early. This observer had appointments at three different Ministries and only one person I was to meet stayed home because it was near the fighting and he chose not to tempt fate.

One government minister smiled knowingly when his visitor commented that between the Dama Rose hotel and his office, although the streets were at that point nearly empty and the sound of mortars was loud, the street cleaners and trash collectors were nonchalantly going about their work. Students of Syrian culture say examples such as this one reflect the deep and unique connections among Syrians for their country–present and past.

It is becoming commonplace, as the world learns more and becomes more distressed about Syria’s Endangered Heritage to speak of this country as the crucible or cradle of human civilization which spans hundreds of thousands of years. This country is home to some of the world’s first cities, as well as globally important sites from the Akkadian, Sumerian, Hittite, Assyrian, Persian, Greco-Roman, Ummayyad, Crusader, and Ottoman civilizations and to some of the oldest, most advanced civilizations in the world.

The area saw our evolution – for example, at the Middle Acheulian occupation site at Latamne northern Syria between 800 – 500,000 years old, stone tools and possibly even early hearths have been identified as belonging to a civilization hundreds of thousands of years before modern humans evolved 120,000 years ago. 10,000 years ago, the first crops and cattle were domesticated in Syria and the subsequent settlements gave rise to the first city states, such as Ebla and Mari. Writing developed here and the creation of literary epics, art, sculpture, and the expansion of trade soon followed. At the crossroads of the Mediterranean, the destined to become modern Syria was invaded by the rise of the great Southern empires emerging from Ur, Bablyon, Assur, Akkad and Sumer. From the East the Persians invaded and occupied the area and then the Mongols and the Arabs. From the North came the Hittites and from the West, the Greeks, the Romans and the Byzantines to be followed by the Crusading forces of the Kings of Europe. Nomadic tribes, known from the Christian Bible, such as the Canaanites and Arameans, arrived and all conquered the area for varying periods and settled. For 400 years Syria was absorbed into the Ottoman Empire and her people revolted and occupation was passed to French after World War I until Syria finally achieved her independence following World War II.

Nowhere else has the world witnessed this complex and unique meeting of states, empires and faiths as Syria. Who can imagine that the great Umayyad Mosque in Damascus was originally a temple to Jupiter? Later converted to a Christian basilica to John the Baptist, and in turn became what some consider the fourth-holiest place in Islam.

Salahdin, the enemy of King Richard the Lionheart, is buried there. And as history continues to leave its ever-changing imprint, in the last thirty years UNESCO has declared six sites in Syria– Syria has 6 such sites including the ancient City of Damascus and a further 12 on the list for Tentative consideration on its World Heritage List. It is from this this rich and diverse history, that Syria’s people have a reputation for tolerance and kindness. Yet now this history, and the peace built upon it, is threatened as never before, and the cultural heritage of all of us, these cross-roads of civilization are quite literally caught in the cross-hairs of war.

Religion has also indelibly marked Syria. This observer has walked through some of the area where Abraham, who influenced three monotheistic religions, pastured sheep at Aleppo and gave the city its Arabic name – Halab. Other visits to religious landmarks have included the old city of Damascus and Straight Street, where tradition holds that the conversion of Saul to Paul the Apostle occurred. Shortly before the events of March 2011, mass was still being held in the house he reputedly inhabited almost 2,000 years ago. The head of the John the Baptist, cousin of Jesus, is said to be enshrined in the Great Mosque in Damascus. The village Maloula is amongst the last places in the world where Aramaic, the language spoken at the time of Jesus, can still be heard – part of a living, breathing, spoken history. Khalid ibn al-Walid, companion to the Prophet Muhammad, founder of Islam, is buried in Homs in his namesake mosque. Muhammad’s successors left a legacy of beautiful mosques: several are now part of World Heritage sites.

When many of us ponder destruction of cultural heritage, we tend to think first of great monuments burning or blasted into rubble. Yet these monuments are about people, and it is with people that all discussions of heritage must begin and finish. Heritage is built by them. It is used and reused by them. Cultural Heritage is also about more than built structures, it is about the intangible beliefs and practices associated with them, and the values assigned to them, including those which may have no material manifestation at all. An analysis of the destruction of Syria’s cultural heritage necessarily encompasses many expressions.

This observer has experienced firsthand locations in Syria where heritage is sometimes at the forefront of the conflict, most notably in the Citadel and Al-Madina Souk in the heart of the Ancient City of Aleppo, a World Heritage site. Conflict in this area has been particularly heavy and damage extensive. The Citadel has taken on a symbolic status to those involved. To militarily control the Citadel is to own the heart of Aleppo, one of the oldest cities in the world.

Yet, ironic as it may seem at first brush, it is during conflict we often see the true, enduring power of heritage to heal and build peace. We have seen in Syria cases where after looters tried to break into the Museums or were caught doing illegal excavations, or trying to sell looted artifacts, that local citizens objected and in some cases risked their lives while confronting criminals and sometimes even blocking access to archeological sites. Such patriotic acts are not just about the protection of the past, but also about the present. We have seen in Syria that after a series of bombings at religious sites, Christians have protected Muslims so that their sisters and brothers can worship in peace, and Muslims in Syria do the same for Churches. These acts of solidarity in Syria, for Syria, are not only bringing the two communities closer together, but they resonates around the world, showing people that peace is possible, and that people of all faiths can work together and are even willing to risk their lives for one another for their shared past- for our shared past, and for each other’s beliefs.

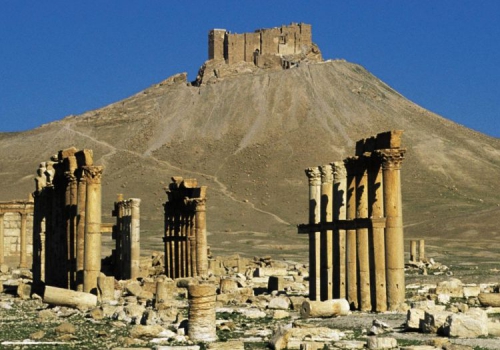

But there is another view. Islamic jihadists have several times explained in great detail to this observer that they want to ruin the artifacts of non-Muslim civilizations, because doing so testifies to the truth of Islam. They always explain that the Qur’an suggests that ruins are a sign of Allah’s punishment of those who rejected his truth. Many were the Ways of Life that have passed away before you: travel through the earth, and see what the end was for those who rejected Truth. (Qur’an 3:137) This is one of the foundations of the Islamic idea that pre-Islamic civilizations, and non-Islamic civilizations, are all jahiliyya — the society of unbelievers, which is worthless. Scores of examples, including ISIS (Da’ish) destroying Assyrian statues and artifacts believed to be 3000 years old which they illegally excavated from the Tell Ajaja site. Museums at Apamea, Aleppo, and Raqqa experienced thefts, and the archaeological sites of Deir ez-Zor, Mari, Dura Europos, Halbia, Buseira, Tell Sheikh Hamad and Tell es-Sin have all been damaged by looters and as of February 2015, five out of six UNESCO world heritage sites in Syria have been damaged by war. Damage to sites like the ancient city of Aleppo and the ruins of Palmyra, Crac des Chevalier and so many others. Nowhere worse than the destruction of the minaret of al-Umayyad mosque in Aleppo in May of 2013.

Daunting as the restoration and repairing these sites may appear, it is a crucial process to foster reconciliation while protecting the heritage that unites all Syrians. People need to rebuild trust and for that to happen, they must have shared memories together. It was a Syrian PhD student, who teamed up with a Dutch archaeology professor, who began documenting the damage to Syrian heritage sites shortly after March of 2011. Soon the work expanded to become a peace-building initiative across Syrian civil society. One of the most remarkable social society NGO’s, now doing many amazing projects is the Spain based Heritage for Peace. (www.heritageforpeace.org ) HFP, like several other private politically neutral groups are working on restoring and repairing these sites as a way to foster reconciliation and it has been achieving much, if on a small scale so far.

The local restoration and repair of damaged sites where security conditions allow will foster reconciliation. As archeological sites are rebuilt so will trust be rebuilt. This observer has experienced this inspiring phenomenon among officials, student volunteers, Syrian army personnel and even rebels. Participants in Syria’s civil war and regular citizens trying to survive the carnage need a basis to rebuild trust and shared memories matter. Hugely. They unite Syrians, pro or anti regime, Syrian locals who refused to leave their home or the three million ex-pats who have fled and want to come home.

The NGO, Heritage for Peace (HFP), is one among others that has studied the destruction in Syria and that believes that heritage can serve as a key focus of dialogue among communities and ethnic and religious groups who have been pitted against one another over the past four years. As part of this process, heritage can become scaffolding for constructing peace in Syria by concentrating on protecting cultural heritage and mitigating damage by galvanizing the public, both local and international, to support heritage protection. Studies show that when citizens caught up in civil war, a movement focused on protecting common cultural heritage fosters compatibility between communities and hastens the postwar phase. Protesting our shared cultural heritage in Syria is showing signs for becoming a peace-building initiative across civil society.

And there is an important role for the global community. What needs to be done now to protect our cultural heritage in Syria which can also help end the conflict are the following measures which all of us can and must participate in. All people of good can work to promote the safeguarding and protection of our cultural heritage in Syria irrespective of religious or ethnic identity. To this end they hopefully will work for goals include the following:

*Document and preserve knowledge of the damages to cultural heritage in Syria during the present conflict while developing long-term policies to protect Syria’s heritage in conflict;

*Raise global awareness of the importance for Syria’s heritage of ending the fighting and stopping its destruction;

*Encourage the co-operation of national and international NGOs who are already working to protect Syria’s heritage and liaise with Syrian heritage workers operating during a current conflict; and the international heritage community;

*Raise global awareness of and campaign against the illicit trade in looted Syrian artifacts globally focusing on the neighboring countries Lebanon, Turkey, Iraq and Jordan and expose those dealers, auction houses and museums who profit from theft of our global heritage in Syria;

*Promote understanding across diverse communities in Syria of the communal value of heritage and encourage foreign archeologists who have previously worked in Syria to provide information and assistance during and after the conflict;

*Promote the return of tourism to Syria and assist in preparations for reconstruction and preservation in the post-conflict phase and the return of international archeologists.

We can help stop the continuing destruction of our global heritage in Syria by this solidarity work. And it can function as a sort of fulcrum to bring an end to Syrian conflict by demonstrating that the people of Syria, custodians of the past of all of us, value this heritage over politics or bizarre religious applications which command that our heritage be destroyed.

Franklin Lamb’s most recent book, Syria’s Endangered Heritage, An international Responsibility to Protect and Preserve is in production by Orontes River Publishing, Hama, Syrian Arab Republic. Inquires c/o orontesriverpublishing@gmail.com. The author is reachable c/o fplamb@gmail.com

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, archéologie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : syrie, arcvhéologie, politique internationale, levant, proche orient |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook