The Lincoln Myth: Ideological Cornerstone of the America Empire

“Lincoln is theology, not historiology. He is a faith, he is a church, he is a religion, and he has his own priests and acolytes, most of whom . . . are passionately opposed to anybody telling the truth about him . . . with rare exceptions, you can’t believe what any major Lincoln scholar tells you about Abraham Lincoln and race.”–Lerone Bennett, Jr., Forced into Glory, p. 114

The author of the above quotation, Lerone Bennett, Jr., was the executive editor of Ebony magazine for several decades, beginning in 1958. He is a distinguished African-American author of numerous books, including a biography of Martin Luther King, Jr. He spent twenty years researching and writing his book, Forced into Glory: Abraham Lincoln’s White Dream, from which he drew the above conclusion about the so-called Lincoln scholars and how they have lied about Lincoln for generations. For obvious reasons, Mr. Bennett is incensed over how so many lies have been told about Lincoln and race.

Few Americans have ever been taught the truth about Lincoln and race, but it is all right there in The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (CW), and in his actions and behavior throughout his life. For example, he said the following:

“Free them [i.e. the slaves] and make them politically and socially our equals? My own feelings will not admit of this . . . . We cannot then make them equals” (CW, vol. II, p. 256.

“What I would most desire would be the separation of the white and black races” (CW, vol. II, p. 521).

“I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and black races . . . . I, as well as Judge Douglas, am in favor of the race to which I belong, having the superior position. I have never said anything to the contrary” (CW, vol. III, p, 16). (Has there ever been a clearer definition of “white supremacist”?).

“I am not, nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races . . . . I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people” (CW, vol. III, pp. 145-146).

“I will to the very last stand by the law of this state [Illinois], which forbids the marrying of white people with negroes” (CW, vol. III, p. 146).

“Senator Douglas remarked . . . that . . . this government was made for the white people and not for the negroes. Why, in point of mere fact, I think so too” (CW, vol. II, p. 281)

Lincoln was also a lifelong advocate of “colonization,” or the deportation of black people from America. He was a “manager” of the Illinois Colonization Society, which procured tax funding to deport the small number of free blacks residing in the state. He also supported the Illinois constitution, which in 1848 was amended to prohibit the immigration of black people into the state. He made numerous speeches about “colonization.” “I have said that the separation of the races is the only perfect preventive of amalgamation . . . . such separation must be effected by colonization” (CW, vol. II, p. 409). And, “Let us be brought to believe it is morally right, and . . . favorable to . . . our interest, to transfer the African to his native clime” (CW, vol. II, p. 409). Note how Lincoln referred to black people as “the African,” as though they were alien creatures. “The place I am thinking about having for a colony,” he said, “is in Central America. It is nearer to us than Liberia” (CW, vol. V, pp. 373-374).

Bennett also documents how Lincoln so habitually used the N word that his cabinet members – and many others – were shocked by his crudeness, even during a time of pervasive white supremacy, North and South. He was also a very big fan of “black face” minstrel shows, writes Bennett.

For generations, the so-called Lincoln scholars claimed without any documentation that Lincoln suddenly gave up on his “dream” of deporting all the black people sometime in the middle of the war, even though he allocated millions of dollars for a “colonization” program in Liberia during his administration. But the book Colonization After Emancipation by Phillip Magness and Sebastian Page, drawing on documents from the British and American national archives, proved that Lincoln was hard at work until his dying day plotting with Secretary of State William Seward the deportation of all the freed slaves. The documents produced in this book show Lincoln’s negotiations with European governments to purchase land in Central America and elsewhere for “colonization.” They were even counting how many ships it would take to complete the task.

Lincoln’s first inaugural address, delivered on March 4, 1861, is probably the most powerful defense of slavery ever made by an American politician. In the speech Lincoln denies having any intention to interfere with Southern slavery; supports the federal Fugitive Slave Clause of the Constitution, which compelled citizens of non-slave states to capture runaway slaves; and also supported a constitutional amendment known as the Corwin Amendment that would have prohibited the federal government from ever interfering in Southern slavery, thereby enshrining it explicitly in the text of the U.S. Constitution.

Lincoln stated at the outset of his first inaugural address that “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” Furthermore, “Those who nominated and elected me did so with full knowledge that I had made this and many similar declarations and had never recanted them; and more than this, they placed in the [Republican Party] platform for my acceptance, and as a law to themselves and to me, the clear and emphatic resolution which I now read: Resolved, that the maintenance inviolate of the rights of the States, and especially the right of each state to order and control its own domestic institutions according to its own judgment exclusively, is essential to the balance of power on which the perfection and endurance of our political fabric depend . . .” By “domestic institutions” Lincoln meant slavery.

Lincoln also strongly supported the Fugitive Slave Clause and the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act in his first inaugural address by reminding his audience that the Clause is a part of the Constitution that he, and all members of Congress, swore to defend. In fact, the Fugitive Slave Act was strongly enforced all during the Lincoln administration, as documented by the scholarly book, The Slave Catchers, by historian Stanley Campbell (University of North Carolina Press, 2011). “The Fugitive Slave Law remained in force and was executed by federal marshals” all during the Lincoln regime, writes Campbell. For example, he writes that “the docket for the [Superior] Court [of the District of Columbia] listed the claims of twenty-eight different slave owners for 101 runaway slaves. In the two months following the court’s decision [that the law was applicable to the District], 26 fugitive slaves were returned to their owners . . .” This was in Washington, D.C., Lincoln’s own residence.

Near the end of his first inaugural address (seven paragraphs from the end) Lincoln makes his most powerful defense of slavery by saying: “I understand a proposed amendment to the Constitution . . . has passed Congress, to the effect that the Federal Government shall never interfere with the domestic institutions of the States, including that of persons held to service [i.e., slaves]. To avoid misconstruction of what I have said, I depart from my purpose not to speak of particular amendments so far as to say that, holding such a provision to now be implied constitutional law, I have no objection to its being made express and irrevocable” (emphasis added).

The Corwin Amendment, named for Rep. Thomas Corwin of Ohio, said:“No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which shall authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any state, the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor [i.e., slaves] or service by the laws of said State.”

After all the Southern members of Congress had left, the exclusively-Northern U.S. Congress voted in favor of the Corwin Amendment by a vote of 133-65 in the House of Representatives on February 28, 1861, and by a vote of 24-12 in the U.S. Senate on March 2, two days before Lincoln’s inauguration.

Lincoln lied in his first inaugural address when he said that he had not seen the Corwin Amendment. Not only did he support the amendment in his speech; it was his idea, as documented by Doris Kearns-Goodwin in her worshipful book on Lincoln entitled Team of Rivals. Based on primary sources, Goodwin writes on page 296 that after he was elected and before he was inaugurated Lincoln “instructed Seward to introduce these proposals in the Senate Committee of Thirteen without indicating they issued from Springfield.” “These proposals” were 1) the Corwin Amendment; and 2) a federal law to nullify personal liberty laws created by several states to allow them to nullify the Fugitive Slave Act.

In 1860-61 Lincoln and the Republican Party fiercely defended Southern slavery while only opposing the extension of slavery into the new territories. They gave three reasons for this:

(1) “Many northern whites . . . wanted to keep slaves out of the [new territories] in order to keep blacks out. The North was a pervasively racist society . . . . Bigots, they sought to bar African-American slaves from the West,” wrote University of Virginia historian Michael Holt in his book, The Fate of Their Country (p. 27).

(2) Northerners did not want to have to compete for jobs with black people, free or slave. Lincoln himself said that “we” want to preserve the territories for “free white labor”.

(3) If slaves were brought into the territories it could inflate the congressional representation of the Democratic Party once a territory became a state because of the three-fifths clause of the Constitution that counted five slaves as three persons for purposes of determining how many congressional representatives each state would have. The Republican Party feared that this might further block their economic policy agenda of high protectionist tariffs to protect Northern manufacturers from competition; corporate welfare for road, canal, and railroad-building corporations; a national bank; and a giving away, rather than selling, of federal land (mostly to mining, timber, and railroad corporations). Professor Holt quotes Ohio Congressman Joshua Giddings explaining: “To give the south the preponderance of political power would be itself to surrender our tariff, our internal improvements [a.k.a. corporate welfare], our distribution of proceeds of public lands . . .” (p. 28).

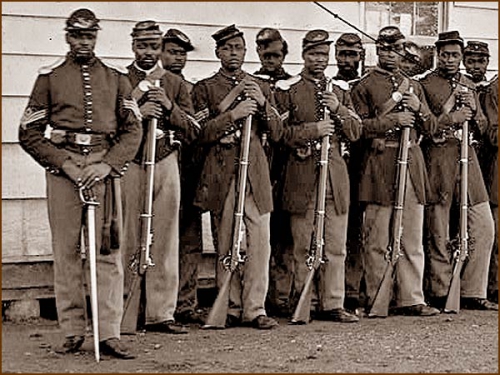

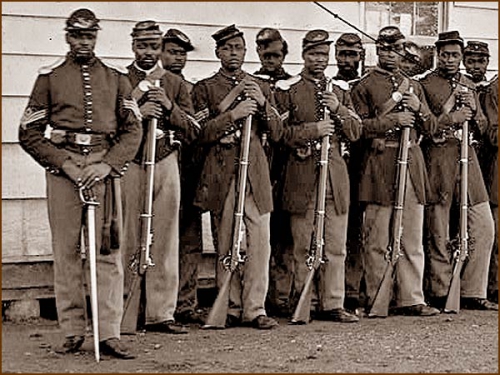

Lincoln called the Emancipation Proclamation a “war measure,” which meant that if the war ended the next day, it would become null and void. It only applied to “rebel territory” and specifically exempted by name areas of the South that were under Union Army control at the time, such as most of the parishes of Louisiana; and entire states like West Virginia, the last slave state to enter the union, having been created during the war by the Republican Party. That is why historian James Randall wrote that it “freed no one.” The apparent purpose was to incite slave rebellions, which it failed to do. Slavery was finally ended in 1866 by the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, with virtually no assistance from Lincoln, as described by Pulitzer prize-winning Lincoln biographer David Donald in his book, Lincoln. On page 545 of his magnum opus David Donald writes of how Lincoln refused to lift a finger to help the genuine abolitionists accumulate votes in Congress for the Thirteenth Amendment. Stories that he did help, such as the false tale told in Steven Spielberg’s movie about Lincoln, are based on pure “gossip,” not documented history, wrote Donald.

Lincoln Promises War Over Tax Collection

In contrast to his compromising stance on slavery, Lincoln was totally and completely uncompromising on the issue of tax collection in his first inaugural address, literally threatening war over it. For decades, Northerners had been attempting to plunder Southerners (and others) with high protectionist tariffs. There was almost a war of secession in the late 1820s over the “Tariff of Abominations” of 1828 that increased the average tariff rate (essentially a sales tax in imports) to 45%. The agricultural South would have been forced to pay higher prices for clothing, farm tools, shoes, and myriad other manufactured products that they purchased mostly from Northern businesses. South Carolina nullified the tariff, refusing to collect it, and a compromise was eventually reached to reduce the tariff rate over a ten-year period.

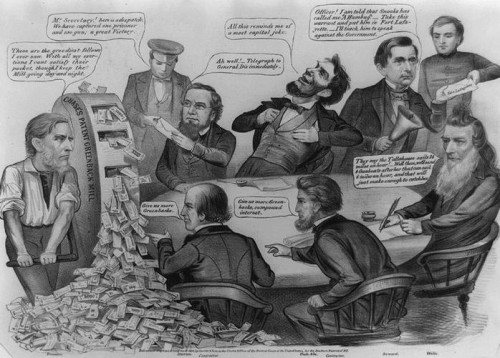

By 1857 the average tariff rate had declined to about 15%, and tariff revenues accounted for at least 90% of all federal tax revenue. This was the high water mark of free trade in the nineteenth century. Then, with the Republican Party in control of Congress and the White House, the average tariff rate was increased, by 1863, back up to 47%, starting with the Morrill Tariff, which was signed into law on March 2, 1861, two days before Lincoln’s inauguration by Pennsylvania steel industry protectionist President James Buchanan. (It had first passed in the House of Representatives during the 1859-60 session).

Understanding that the Southern states that had seceded and had no intention of continuing to send tariff revenues to Washington, D.C., Lincoln threatened war over it. “[T]here needs to be no bloodshed or violence,” he said in his first inaugural address, “and there shall be none unless it is forced upon the national authority.”

And what could “force” the “national authority” to commit acts of “violence” and “bloodshed”? Lincoln explained in the next sentence: “The power confided in me will be used to hold, occupy, and possess the property and places belonging to the Government and to collect the duties and imposts; but beyond what may be necessary for these objects, there will be no invasion, no using of force against or among the people anywhere.” “Pay up or die; the American union is no longer voluntary” was his principal message. In Lincoln’s mind, the union was more like what would become the Soviet union than the original, voluntary union of the founding fathers. He kept his promise by invading the Southern states with an initial 75,000 troops after duping South Carolinians into firing upon Fort Sumter (where no one was harmed, let alone killed).

The Stated Purpose of the War

The U.S. Senate issued a War Aims Resolution that said: “[T]his war is not waged . . . in any spirit of oppression, or for any purpose of conquest or subjugation, or purpose of overthrowing or interfering with the rights or established institutions of those [Southern] states, but to defend . . . the Constitution, and to preserve the Union . . .” By “established institutions” of the Southern states they meant slavery.

Like the U.S. Senate, Lincoln also clearly stated that the purpose of the war was to “save the union” and not to interfere with Southern slavery. In a famous August 22, 1862 letter to New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley, he wrote that:

“My paramount objective in this struggle is to save the Union, and it is not either to save or destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.” Of course, Lincoln’s war destroyed the voluntary union of the founding fathers and replaced it with an involuntary union held together by threat of invasion, bloodshed, conquest, and subjugation.

The Very Definition of Treason

Treason is defined by Article 3, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution as follows: “Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort.” The most important word here is “them.” As in all the founding documents, “United States” is always in the plural, signifying that the “free and independent states,” as they are called in the Declaration of Independence, are united in forming a compact or confederacy with other states. Levying war against “them” means levying war against individual states, not something called “the United States government.” Therefore, Lincoln’s invasion and levying of war upon the Southern states is the very definition of treason in the Constitution.

Lincoln took it upon himself to arbitrarily redefine treason, not by amending the Constitution, but by using brute military force. His new definition was any criticism of himself, his administration, and his policies. He illegally suspended the writ of Habeas Corpus (illegal according to this own attorney general, Robert Bates) and had the military arrest and imprison without due process tens of thousands of Northern-state citizens, including newspaper editors, the Maryland legislature, the mayor of Baltimore, the grandson of Francis Scott Key who was a Baltimore newspaper editor, Congressman Clement L. Vallandigham of Ohio, his chief critic in the U.S. Congress, and essentially anyone overheard criticizing the government. (See Freedom Under Lincoln by Dean Sprague and Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln by James Randall).

More than 300 Northern newspapers were shut down for criticizing the Lincoln regime as documented by James Randall, the preeminent Lincoln scholar of the twentieth century.

Lincoln’s Real Agenda: A Mercantilist Empire

Lincoln began his political career in 1832 as a Whig. Northern Whigs like Lincoln were the party of the corporate plutocracy who wanted to use the coercive powers of government to line the pockets of their big business benefactors (and of themselves). They proclaimed to stand for what their political predecessor, Alexander Hamilton, called the “American System.” This was really an Americanized version of the rotten, corrupt system of British “mercantilism” that the colonists had rebelled against. Its planks included protectionist tariffs to benefit Northern manufacturers and their banking and insurance industry business associates; a government-run national bank to provide cheap credit to politically-connected businesses; and “internal improvement subsidies,” which we today would call “corporate welfare,” for canal-, road-, and railroad-building corporations. So when Lincoln first ran for political office in Illinois in 1832 he announced: “I am humble Abraham Lincoln. I have been solicited by many friends to become a candidate for the legislature. My politics are short and sweet, like the old woman’s dance. I am in favor of a national bank . . . in favor of the internal improvements system and a high protective tariff.” He would devote his entire political career for the next twenty-nine years on that agenda.

The major opposition to Lincoln’s agenda of a mercantilist empire modeled after the British empire had always been from the South, as Presidents Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Jackson, and Tyler, among others, vetoed or obstructed Whig and later, Republican, legislation. There were Southern supporters of this agenda, and Northern, Jeffersonian opponents of it, but it is nevertheless true that the overwhelming opposition to this Northern, Hamiltonian scheme came from the Jeffersonian South.

Henry Clay was the leader of the Whigs until his death in 1852, and Lincoln once claimed that he got all of his political ideas from Clay, who he eulogized as “the beau ideal of a statesman.” In reality, the Hamilton/Clay/Lincoln “American System” was best described by Edgar Lee Masters, who was Clarence Darrow’s law partner and a renowned playwright (author of The Spoon River Anthology). In his book, Lincoln the Man (p. 27), Masters wrote that:“Henry clay was the champion of that political system which doles favors to the strong in order to win and to keep their adherence to the government. His system offered shelter to devious schemes and corrupt enterprises . . . He was the beloved son of Alexander Hamilton with his corrupt funding schemes, his superstitions concerning the advantage of a public debt, and a people taxed to make profits for enterprises that cannot stand alone. His example and his doctrines led to the creation of a party that had not platform to announce, because its principles were plunder and nothing else.”

This was the agenda that Abraham Lincoln devoted his entire political life to. The “American System” was finally fully enacted with Lincoln’s Pacific Railroad Bill, which led to historic corruption during the Grant administration with its gargantuan subsidies to railroad corporations and others; fifty years of high, protectionist tariffs that continued to plunder Agricultural America, especially the South and the Mid-West, for the benefit of the industrial North; the nationalization of the money supply with the National Currency Acts and Legal Tender Acts; and the beginnings of a welfare state with veterans’ pensions. Most importantly, the system of federalism that was established by the founding fathers was all but destroyed with a massive shift in political power to Washington, D.C. and away from the people, due to the abolition (at gunpoint) of the rights of nullification and secession.

Lincoln’ Biggest Failure

Slavery was ended peacefully everywhere else in the world during the nineteenth century. This includes Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New York, where slaves were once used to build slave ships that sailed out of New York, Providence, Hartford, Providence, and Boston harbors. There were still slaves in New York City as late as 1853.

Nobel prize-winning economist Robert Fogel and co-author Stanley Engerman, in their book, Time on the Cross, describe how the British, Spanish, and French empires, as well as the Swedes, Danes, and Dutch, ended slavery peacefully during the nineteenth century. Whenever slaves did participate in wars in Central America and elsewhere, it was because they were promised freedom by one side in the war; the purpose of the wars, however, was never to free the slaves.

The British simply used tax dollars to purchase the freedom of the slaves and then legally ended the practice. The cost of the “Civil War” to Northern taxpayers alone would have been sufficient to achieve the same thing in the U.S. Instead, the slaves were used as political pawns in a war that ended with the death of as many as 850,000 Americans according to the latest research (the number was 620,000 for the past 100 years or so), with more than double that amount maimed for life, physically and psychologically. (Lincoln did make a speech in favor of “compensated emancipation” in the border states but insisted that it be accompanied by deportation of any emancipated slaves. He never used his “legendary” political skills, however, to achieve any such outcome, as a real statesman would have done – minus the deportation).

The Glory of the Coming of the Lord?

By the mid nineteenth century the world had evolved such that international law and the laws of war condemned the waging of war on civilians. It was widely recognized that civilians would always become casualties in any war, but to intentionally target them was a war crime.

The Lincoln regime reversed that progress and paved the way for all the gross wartime atrocities of the twentieth century by waging war on Southern civilians for four long years. Rape, pillage, plunder, the bombing and burning of entire cities populated only by civilians was the Lincolnian way of waging war – not on foreign invaders but on his own fellow American citizens. (Lincoln did not consider secession to be legal; therefore, he thought of all citizens of the Southern states to be American citizens, not citizens of the Confederate government).

General Sherman said in a letter to his wife that his purpose was “extermination, not of soldiers alone, that is the least part of the trouble, but the people” (Letter from Sherman to Mrs. Sherman, July 31, 1862). Two years later, he would order his artillery officers to use the homes of Atlanta occupied by women and children as target practice for four days, while much of the rest of the city was a conflagration. The remaining residents were then kicked out of their homes – in November with the onset of winter. Ninety percent of Atlanta was demolished after the Confederate army had left the city.

General Philip Sheridan similarly terrorized the civilians of the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia. All of this led historian Lee Kennett, in his biography of Sherman, to honestly state that “had the Confederates somehow won, had their victory put them in position to bring their chief opponents before some sort of tribunal, they would have found themselves justified . . . in stringing up President Lincoln and the entire Union high command for violation of the laws of war, specifically for waging war against noncombatants” (Lee Kennett, Marching Through Georgia: The Story of Soldiers and Civilians During Sherman’s Campaign, p. 286).

About All Those Statues

Professor Murray N. Rothbard (1926-1995) was perhaps the most famous academic libertarian in the world during the last half of the twentieth century. A renowned Austrian School economist, he also wrote widely on historical topics, especially war and foreign policy. In a 1994 essay entitled “Just War” (online at https://mises.org/library/just-war), Rothbard argued that the only two American wars that would qualify as just wars (defined as wars to ward off a threat of coercive domination) were the American Revolution and the South’s side in the American “Civil War.” Without getting into his detailed explanation of this, his conclusion is especially relevant and worth quoting at length:

“[I]n this War Between the States, the South may have fought for its sacred honor, but the Northern war was the very opposite of honorable. We remember the care with which the civilized nations had developed classical international law. Above all, civilians must not be targeted; wars must be limited. But the North insisted on creating a conscript army, a nation in arms, and broke the 19th-century rules of war by specifically plundering and slaughtering civilians, by destroying civilian life and institutions so as to reduce the South to submission. Sherman’s famous march through Georgia was one of the great war crimes, and crimes against humanity, of the past century-and-a-half. Because by targeting and butchering civilians, Lincoln and Grant and Sherman paved the way for all the genocidal horrors of the monstrous 20th century. . . . As Lord Acton, the great libertarian historian, put it, the historian, in the last analysis, must be a moral judge. The muse of the historian, he wrote, is not Clio but Rhadamanthus, the legendary avenger of innocent blood. In that spirit, we must always remember, we must never forget, we must put in the dock and hang higher than Haman, those who, in modern times, opened the Pandora’s Box of genocide and the extermination of civilians: Sherman, Grant, and Lincoln.

Perhaps, some day, their statues will be toppled and melted down; their insignias and battle flag will be desecrated, and their war songs tossed into the fire.

Perhaps, some day. But in the meantime, and for the past 150 years, the mountain of lies that has concocted the Lincoln Myth has been invoked over and over again to “justify” war after war, all disguised as some great moral crusade, but in reality merely a tool to enrich the already wealthy-beyond-their-wildest-dreams military/industrial complex and its political promoter class. As Robert Penn Warren wrote in his 1960 book, The Legacy of the Civil War, the Lincoln Myth, painstakingly fabricated by the Republican Party, long ago created a “psychological heritage” that contends that “the Northerner, with his Treasury of Virtue” caused by his victory in the “Civil War,” feels as though he has “an indulgence, a plenary indulgence, for all sins past, present, and future.” This “indulgence,” wrote Warren, “is the justification for our crusades of 1917-1918 and 1941-1945 and our diplomacy of righteousness, with the slogan of unconditional surrender and universal rehabilitation for others” (emphasis added). Robert Penn Warren believed that most Americans were content with all of these lies about their own history, the work of what he called “the manipulations of propaganda specialists,” referring to those who describe themselves as “Lincoln scholars.”

The Best of Thomas DiLorenzo

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg