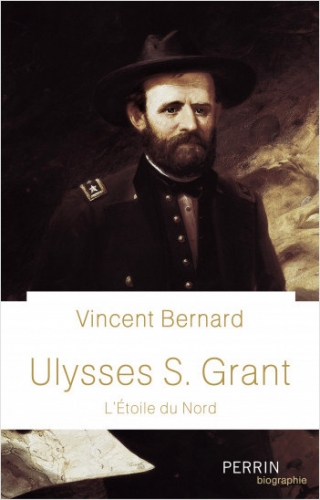

Ulysses S. Grant n’a pas eu une vie mais plusieurs. Vincent Bernard nous fait découvrir celui qui fut tour à tour, un enfant timide et effacé de l’Ohio, un fermier malhabile du Missouri, un employé obscur et sans grand talent de l’Illinois, un cavalier émérite de West Point, un soldat courageux lors de la guerre du Mexique, général des armées « nordistes », et enfin président des États-Unis d’Amérique. Il est également connu comme le reconstructeur de l’Union, et surtout « l’Étoile du Nord et Némésis du Sud ». Sherman, son ami et bras droit, écrit en 1865 : « Pour moi, Grant est un mystère et je crois qu’il est mystère pour lui même. » C’est ce mystère que tente de percer Vincent Bernard. L’auteur est historien de formation (Université Montaigne – Bordeaux III), enseignant puis rédacteur en chef de magazines d’histoire dans les années 2000. Il est surtout connu pour être le premier biographe français de Robert E. Lee et d’Ulysses S. Grant.

Ulysses S. Grant n’a pas eu une vie mais plusieurs. Vincent Bernard nous fait découvrir celui qui fut tour à tour, un enfant timide et effacé de l’Ohio, un fermier malhabile du Missouri, un employé obscur et sans grand talent de l’Illinois, un cavalier émérite de West Point, un soldat courageux lors de la guerre du Mexique, général des armées « nordistes », et enfin président des États-Unis d’Amérique. Il est également connu comme le reconstructeur de l’Union, et surtout « l’Étoile du Nord et Némésis du Sud ». Sherman, son ami et bras droit, écrit en 1865 : « Pour moi, Grant est un mystère et je crois qu’il est mystère pour lui même. » C’est ce mystère que tente de percer Vincent Bernard. L’auteur est historien de formation (Université Montaigne – Bordeaux III), enseignant puis rédacteur en chef de magazines d’histoire dans les années 2000. Il est surtout connu pour être le premier biographe français de Robert E. Lee et d’Ulysses S. Grant.

Grant écrit à la fin de sa vie : « J’ai peu lu de vies de grands hommes, car les biographes se font une règle de ne pas en dire assez de la période formatrice de la vie. Ce que je veux savoir c’est ce qu’un homme a fait quand il était enfant. » Prenons donc le temps d’évoquer ses origines familiales et sociales en nous attardant, quelques instants, sur la figure du père d’Ulysses. « Grant père s’était forgé au feu d’une jeunesse particulièrement difficile, vécue dans une hantise extrême de la pauvreté, du dénuement et de l’abandon, nourrissant un sens aigu du travail, de l’effort et du gain. En corollaire il avait développé une violente aversion pour les vices sudistes, présentés comme amollissant le corps et l’esprit, à commencer par le tabac, l’alcool et l’esclavage » et Bernard poursuit : « Non pas que cette dernière institution eut été perçue moralement comme une atteinte au droit des Noirs de vivre libres et égaux, mais bien plutôt comme un vice instillant la paresse, chez le maître en le déchargeant des dures obligations du labeur quotidien. ». Au sujet de la mère de Grant, voici ce qu’en dit l’auteur : « Hannah Simpson Grant, femme effacée et secrète de ses mots, et de ses élans, que certains iront la penser jusque mentalement déficiente et que son célèbre fils n’évoquera presque jamais dans ses mémoires. » Le décor familial est planté.

Grant naît dans une famille de la classe moyenne inférieure aux conditions de vie précaires. « L’histoire de Grant débute le samedi 27 avril 1822 dans une brinquebalante masure de bois louée deux dollars par mois dans le tout jeune état pionnier de l’Ohio sur la berge de la rivière du même nom. » L’auteur donne des précisions sur l’enfance de Grant. « Fréquentant tôt les très modestes écoles du voisinage, entretenues par souscription des habitants, où se côtoient enfants et adolescents de tous âges, en une classe unique, il n’y brille pas particulièrement mais est déjà singulièrement qualifié de lent et sûr, dans son travail, empreint d’une distinction modeste qui le signale comme une personnalité à part, taciturne et réservé, fortement, a-t-on dit, influencé par le caractère maternel. » Grant père, après un dur labeur, parvient à s’élever dans cette société pionnière et il dirige avec succès une tannerie. Celle-ci permet à la famille de Grant de mieux vivre et de s’élever socialement. Ulysses n’apprécie guère ce travail et supporte mal les émanations du cuir. Un jour, son père lui intime l’ordre d’exécuter une tâche. Il répond : « Je vais le faire, mais dès que j’aurai l’âge, je ne mettrai plus jamais les pieds à la tannerie. » Ulysses souhaite entreprendre des études longues, mais les écoles coûtent cher et sa famille ne dispose pas de moyens financiers conséquents pour payer l’inscription. Finalement, il s’inscrit à West Point grâce aux solides amitiés familiales. Il devient, après quatre ans, le 1187e cadet de cette prestigieuse académie militaire depuis sa fondation en 1802. Rapidement Grant s’aperçoit que la vie militaire lui pèse. Il déclare que « la vie militaire n’avait aucun attrait pour lui ». Il ne goûte donc que modérément à la vie de camp, aux bivouacs et au fait de dormir sous la tente. L’auteur précise : « Jamais plus après ce long été 1843, Grant ne verra la vie militaire avec les yeux plein d’espoir et de fierté du jeune cadet de West Point. » Effectivement, il songe déjà à quitter l’armée, mais se demande bien comment il pourra subvenir aux besoins de sa future famille. Les questions d’argent reviennent souvent dans la vie de Grant, lui qui ne profitera jamais de ses différentes et avantageuses positions pour s’enrichir honnêtement ou malhonnêtement…

Au cours d’une permission, il rend visite à un collègue de West Point, Frederik Dent, et rapidement Grant se rapproche sa sœur Julia. S’en suit une longue correspondance, agrémentée de rares visites, carrière militaire oblige. Grant désire faire de Julia son épouse. Bien que n’étant un abolitionniste, Grant ne partage pas les idées politiques de sa belle-famille « sudiste ». De plus, il doit faire face à l’hostilité de son futur beau-père. « Le colonel Dent ne cache pas son mépris pour la condition militaire et la vie de garnison promise à sa fille, si elle épousait un officier. » L’union est finalement approuvée par les deux familles. Par la suite, Grant participe à la guerre contre le Mexique, au sujet de l’annexion du Texas et se fait remarquer comme brillant cavalier. Il est présent avec succès à la bataille du Resaca de la Palma et à la bataille de Monterrey. La guerre est remportée assez facilement malgré tout. Il propose une vision très claire de ce conflit. « Grant analyse la guerre du Mexique avec hauteur et recul, d’un point de vue militaire et aussi politique. Conflit injuste et prédateur, impie même, écrit l’agnostique, provoquée sciemment contre une puissance plus faible, son déroulement militaire même découle de calculs politiques et de la crainte de voir émerger un général trop victorieux susceptible de devenir un adversaire politique. » Après plus de trois longues années, il retrouve Julia avec laquelle il s’était fiancé secrètement. Ils se marient. Seule une des sœurs de Grant est présente au mariage. Ses parents prétextent le manque de temps de préparation pour justifier leur absence à la noce. En réalité, ils ne veulent pas sympathiser avec une belle famille aux tendances esclavagistes. Après la guerre, il connaît la vie de garnison et ne supporte pas les différentes contraintes de la vie militaire. Grant pense que ses supérieurs veulent l’humilier, alors qu’ils appliquent de manière stricte et étroite le code militaire. Il finit par démissionner. S’ouvre alors une traversée du désert qui dure sept ans, de 1854 à 1861.

Il s’agit pour les Grant, d’une période familiale heureuse, mais difficile sur le plan économique, nonobstant l’aide matérielle et financière de la belle-famille. Il devient fermier et se voit très bien dans ce nouveau métier. « Pour quiconque entendra parler de moi dans dix ans, ce sera en tant que vieux fermier missourien accompli. » Il n’est pas doué dans les affaires, l’activité agricole se montre guère florissante. Il se pose même la question de revenir chez ses parents, pour travailler dans la tannerie familiale. Il se lance également dans la vente de produits divers et variés, notamment en cuir, sans plus de succès. La famille Grant s’agrandit. Le couple aura quatre enfants. L’appel de Lincoln de 1861 pour lever 75 000 volontaires pour 90 jours afin de combattre la rébellion naissante le conduit, sans hésitation aucune, à rejoindre l’armée. La Guerre Civile dure quatre longues années, alors que tous les belligérants prévoyaient une guerre courte. Bernard décrit parfaitement les enjeux politiques et stratégiques de ce conflit, qui reste à ce jour le plus meurtrier auquel ont participé les États-Unis d’Amérique. Nous suivons Grant dans ces principales batailles : Shiloh, Vicksburg Chattanooga, etc., et manœuvres tactiques. Sa réputation se construit rapidement. Amis et ennemis le voient comme un jusqu’au-boutiste qui ne recule devant rien pour l’exécution de ses plans. Certains l’accusent d’être indolent, imprudent voire alcoolique. Lincoln loin de s’en séparer le défend, expliquant que c’est un des rares généraux à remporter des batailles et à porter de rudes coups à la Confédération. Il reçoit la Médaille d’or en 1863, qui est la plus haute distinction civile qui puisse être accordée par le Congrès. 1863 marque donc un tournant personnel pour Grant et pour la poursuite de la guerre. Effectivement, après la défaite de Gettysburg, les États confédérés perdent l’initiative et ne peuvent plus remporter la guerre. De plus, il devient également général en chef des armées de l’Union. Grant se retrouve seul pour affronter Lee, durant une série de sanglantes batailles regroupées sous le nom de « Overland Campaign ». Bien que Grant subisse de terribles pertes et de multiples défaites tactiques au cours de cette campagne, elle est considérée comme une victoire stratégique de l’Union, car elle conduit Lee à s’enfermer dans la ville assiégée de Petersburg. Beaucoup n’apprécient pas le style militaire de Grant et ses victoires à la Pyrrhus, à commencer par la femme du président Lincoln, Mary Tood Lincoln. « Grant est un boucher, indigne d’être à la tête de notre armée. Il s’arrange généralement pour revendiquer la victoire, mais quelle victoire. Il perd deux hommes alors que l’ennemi un seul. Il ne sait pas diriger, n’a aucun respect pour la vie. Si la guerre devait durer quatre ans de plus, et qu’il reste au pouvoir, il dépeuplerait le Nord. Je pourrais tout aussi bien conduire une armée moi-même. » Il convient de préciser, non pour nuancer ce propos mais pour l’éclairer, que plusieurs membres de la famille de Mary Tood, notamment ses frères, combattaient sous l’uniforme gris.

Grant est lucide au sujet de cette Guerre Civile. Voici comment il la considère. « La rébellion du Sud fut l’avatar de la guerre avec le Mexique. Nations et individus sont punis de leurs transgressions. Nous reçûmes notre châtiment sous la forme de la plus sanguinaire et coûteuse guerre des temps modernes. » Lui l’agnostique la juge comme un châtiment suite à l’agression étasunienne à l’endroit du Mexique, nation jugée plus faible, lors de la guerre américano-mexicaine de 1846 – 1848. Grant note par la suite, que le carnage de Shiloh lui avait fait réaliser que la Confédération ne pourrait être vaincue que par la destruction complète de ses armées. Dans les premiers temps, la Guerre Civile est presque considérée comme une guerre en dentelles, on la définit même comme une guerre de gentlemans. Très vite cette guerre se transforme et les acteurs et observateurs parlent alors à son sujet de rivières et de fleuves de sang. La guerre est remportée par le Nord, après tant d’efforts et de sacrifices. Grant écrit à ce sujet qu’il est « moins facile de sortir d’une guerre que d’y rentrer ». Le Sud et son brillant général en chef Lee finissent donc par être vaincus. Concrètement, les Sudistes succombent à la force numérique et industrielle de l’Union qui surpassent de loin, le courage et la supériorité tactique militaire de la Confédération. Une fois la paix faite, il faut noter que Grant est un fervent partisan de la modération et de la réintégration des Sudistes dans l’Union. « La guerre est terminée, les rebelles sont à nouveau nos compatriotes, et la meilleure manière de se réjouir après la victoire sera de s’abstenir de toute démonstration. »

Grant est lucide au sujet de cette Guerre Civile. Voici comment il la considère. « La rébellion du Sud fut l’avatar de la guerre avec le Mexique. Nations et individus sont punis de leurs transgressions. Nous reçûmes notre châtiment sous la forme de la plus sanguinaire et coûteuse guerre des temps modernes. » Lui l’agnostique la juge comme un châtiment suite à l’agression étasunienne à l’endroit du Mexique, nation jugée plus faible, lors de la guerre américano-mexicaine de 1846 – 1848. Grant note par la suite, que le carnage de Shiloh lui avait fait réaliser que la Confédération ne pourrait être vaincue que par la destruction complète de ses armées. Dans les premiers temps, la Guerre Civile est presque considérée comme une guerre en dentelles, on la définit même comme une guerre de gentlemans. Très vite cette guerre se transforme et les acteurs et observateurs parlent alors à son sujet de rivières et de fleuves de sang. La guerre est remportée par le Nord, après tant d’efforts et de sacrifices. Grant écrit à ce sujet qu’il est « moins facile de sortir d’une guerre que d’y rentrer ». Le Sud et son brillant général en chef Lee finissent donc par être vaincus. Concrètement, les Sudistes succombent à la force numérique et industrielle de l’Union qui surpassent de loin, le courage et la supériorité tactique militaire de la Confédération. Une fois la paix faite, il faut noter que Grant est un fervent partisan de la modération et de la réintégration des Sudistes dans l’Union. « La guerre est terminée, les rebelles sont à nouveau nos compatriotes, et la meilleure manière de se réjouir après la victoire sera de s’abstenir de toute démonstration. »

Cependant comme le dit l’auteur, l’après-guerre se montre confuse et ouvre une période très compliquée dans l’histoire américaine. « La Reconstruction témoigne des paradoxes d’une Amérique à la fois réunie et déchirée. La Guerre Civile est achevée. Le Nord est victorieux mais soucieux de tourner une page sanglante et de reprendre sa marche vers son destin particulier. Le Sud est ruiné et résigné, mais arbore toujours fièrement les stigmates de sa lutte avortée et de sa cause perdue, cherchant à reconstituer, au détriment des populations noires affranchies, les oripeaux de son paradis perdu. » L’abolition de l’esclavage et la reconnaissance des droits civiques des populations noires n’étaient pas partagées par nombre d’Américains, à commencer par les Nordistes eux-mêmes. « J’admets que les Nègres ne sont pas assez intelligents pour voter, mais jusqu’à quel point sont-ils plus ignorants que la population blanche illettrée du Sud ? » dit John Sherman, sénateur de l’Ohio et frère du général Sherman, le fidèle séide de Grant. Ce dernier écrit également. « J’ai recommandé que le président devrait autoriser à lever 20 000 troupes de couleur en cas de nécessité, mais ne recommande pas l’emploi permanent de troupes de couleur, parce que notre armée en temps de paix devrait être la plus petite et efficace possible. En temps de paix, je pense que l’artillerie utilisée en tant qu’école de formation sera plus efficace si composée exclusivement de Blancs. » Finalement les lois de ségrégations raciales sont définitivement abolies aux Etats-Unis d’Amérique en 1964 après leur mise en vigueur dès 1876.

Après avoir été le premier personnage de l’armée, il devient l’homme le plus important de son pays en devenant le 18e président de la jeune nation américaine pour deux mandats (1868 – 1877). Bernard décrypte parfaitement les mécanismes humains et politiques qui poussent Grant à se présenter et à conquérir la magistrature suprême. Toutefois, il existe un énorme paradoxe dont souffre Grant sa vie durant et qui continue une fois celui-ci enterré, comme nous l’explique l’écrivain. « Pourtant, si Ulysses S. Grant est demeuré profondément ancré dans la mémoire et l’histoire américaines, c’est bien plus au titre du général en chef de l’Union victorieux en 1865 qu’à celui du Président aux ambitions réconciliatrices dirigeant de 1869 à 1877 une nation en pleine reconstruction politique et aspirant tout à la fois à achever son expansion messianique vers les grands déserts de l’Ouest et son ascension au rang de véritable puissance mondiale. » Effectivement ses deux mandats présidentiels sont marqués par les dissensions du Parti républicain, la panique bancaire de 1873 et la corruption de son administration. Plusieurs de ses proches collaborateurs s’enrichissent malhonnêtement, profitant de la double situation exceptionnelle d’alors qui permet toutes les tripatouillages possibles : la conquête de l’Ouest et la reconstruction du Sud. Grant subit les contrecoups de ses affaires de corruption et de malversation, bien qu’il ne soit jamais directement soupçonné ou rendu coupable par les tribunaux. Sa probité ne peut être mise en cause, mais certains lui reprochent un manque évident de charisme, dont ne souffrait pas son ancien adversaire le général Lee. Cependant, laissons parler John Wisse qui nous brosse un portrait de Grant bien différent de l’image qu’il a laissée dans l’historiographie. « Nul homme ne pouvait échanger un moment avec Grant sans ressentir de l’admiration pour ses talents ainsi que du respect. C’était un homme des plus simple et digne de confiance. La plus grande erreur jamais faite par le peuple sudiste fut de ne pas réaliser que s’il le lui avait permis, il aurait été son meilleur ami après la guerre. » Preuve d’une popularité certaine qui se dégradera pourtant très vite avec le temps, des millions de personnes, de civils, de politiques, d’anciens soldats de l’armée de l’Union, de jeunes cadets de West Point, etc., assistent à son enterrement et lui rendent hommage par la suite. Son corps repose dans un sarcophage situé dans l’atrium du General Grant National Memorial achevé en 1897; avec 50 mètres de haut, il est le plus grand mausolée d’Amérique du Nord.

De son vivant et après sa mort, d’aucuns opposeront le « bon général » au « mauvais président ». Les choses sont en réalité plus complexes. La très intéressante biographie de Bernard nous permet de percer le « mystère » Grant. Les analyses proposées sont réellement intéressantes et ce livre nous donne à découvrir un homme, finalement assez commun, mais qui eut une vie et une carrière exceptionnelles. L’enfant timide de l’Ohio, le mauvais homme d’affaires, le soldat qui n’appréciait ni la guerre, ni la vie militaire remporta la Guerre Civile, et fut par deux fois président de la plus grande puissance de ce bas-monde, lui qui aimait tant la simplicité de la vie de famille et monter ses chevaux.

De son vivant et après sa mort, d’aucuns opposeront le « bon général » au « mauvais président ». Les choses sont en réalité plus complexes. La très intéressante biographie de Bernard nous permet de percer le « mystère » Grant. Les analyses proposées sont réellement intéressantes et ce livre nous donne à découvrir un homme, finalement assez commun, mais qui eut une vie et une carrière exceptionnelles. L’enfant timide de l’Ohio, le mauvais homme d’affaires, le soldat qui n’appréciait ni la guerre, ni la vie militaire remporta la Guerre Civile, et fut par deux fois président de la plus grande puissance de ce bas-monde, lui qui aimait tant la simplicité de la vie de famille et monter ses chevaux.

Franck Abed

• Vincent Bernard, Ulysses S. Grant. L’Étoile du Nord, Éditions Perrin, coll. « Biographies », 2018, 400 p., 23 €.

• D’abord mis en ligne sur Fréquence Histoire, le 3 février 2018.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

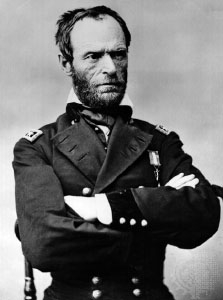

Matthew Carr’s new book,

Matthew Carr’s new book,  Sherman believed that his nastiness would turn the South against war. “Thousands of people may perish,” he said, “but they now realize that war means something else than vain glory and boasting. If Peace ever falls to their lot they will never again invite War.” Some imagine this to be the impact the U.S. military is having on foreign nations today. But have Iraqis grown more peaceful? Does the U.S. South lead the way in peace activism? When Sherman raided homes and his troops employed “enhanced interrogations” — sometimes to the point of death, sometimes stopping short — the victims were people long gone from the earth, but people we may be able to “recognize” as people. Can that perhaps help us achieve the same mental feat with the current residents of Western Asia? The U.S. South remains full of monuments to Confederate soldiers. Is an Iraq that celebrates today’s resisters 150 years from now what anyone wants?

Sherman believed that his nastiness would turn the South against war. “Thousands of people may perish,” he said, “but they now realize that war means something else than vain glory and boasting. If Peace ever falls to their lot they will never again invite War.” Some imagine this to be the impact the U.S. military is having on foreign nations today. But have Iraqis grown more peaceful? Does the U.S. South lead the way in peace activism? When Sherman raided homes and his troops employed “enhanced interrogations” — sometimes to the point of death, sometimes stopping short — the victims were people long gone from the earth, but people we may be able to “recognize” as people. Can that perhaps help us achieve the same mental feat with the current residents of Western Asia? The U.S. South remains full of monuments to Confederate soldiers. Is an Iraq that celebrates today’s resisters 150 years from now what anyone wants?