& http://www.lewrockwell.com

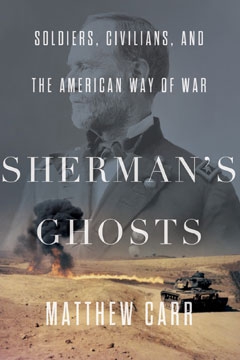

Matthew Carr’s new book, Sherman’s Ghosts: Soldiers, Civilians, and the American Way of War, is presented as “an antimilitarist military history” — that is, half of it is a history of General William Tecumseh Sherman’s conduct during the U.S. Civil War, and half of it is an attempt to trace echoes of Sherman through major U.S. wars up to the present, but without any romance or glorification of murder or any infatuation with technology or tactics. Just as histories of slavery are written nowadays without any particular love for slavery, histories of war ought to be written, like this one, from a perspective that has outgrown it, even if U.S. public policy is not conducted from that perspective yet.

Matthew Carr’s new book, Sherman’s Ghosts: Soldiers, Civilians, and the American Way of War, is presented as “an antimilitarist military history” — that is, half of it is a history of General William Tecumseh Sherman’s conduct during the U.S. Civil War, and half of it is an attempt to trace echoes of Sherman through major U.S. wars up to the present, but without any romance or glorification of murder or any infatuation with technology or tactics. Just as histories of slavery are written nowadays without any particular love for slavery, histories of war ought to be written, like this one, from a perspective that has outgrown it, even if U.S. public policy is not conducted from that perspective yet.

What strikes me most about this history relies on a fact that goes unmentioned: the former South today provides the strongest popular support for U.S. wars. The South has long wanted and still wants done to foreign lands what was — in a much lesser degree — done to it by General Sherman.

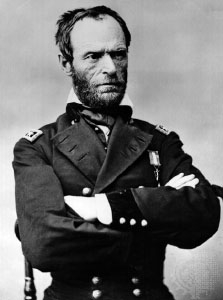

What disturbs me most about the way this history is presented is the fact that every cruelty inflicted on the South by Sherman was inflicted ten-fold before and after on the Native Americans. Carr falsely suggests that genocidal raids were a feature of Native American wars before the Europeans came, when in fact total war with total destruction was a colonial creation. Carr traces concentration camps to Spanish Cuba, not the U.S. Southwest, and he describes the war on the Philippines as the first U.S. war after the Civil War, following the convention that wars on Native Americans just don’t count (not to mention calling Antietam “the single most catastrophic day in all U.S. wars” in a book that includes Hiroshima). But it is, I think, the echo of that belief that natives don’t count that leads us to the focus on Sherman’s march to the sea, even as Iraq, Afghanistan, and Gaza are destroyed with weapons named for Indian tribes. Sherman not only attacked the general population of Georgia and the Carolinas on his way to Goldsboro — a spot where the U.S. military would later drop nuclear bombs (that very fortunately didn’t explode) — but he provided articulate justifications in writing, something that had become expected of a general attacking white folks.

What intrigues me most is the possibility that the South today could come to oppose war by recognizing Sherman’s victims in the victims of U.S. wars and occupations. It was in the North’s occupation of the South that the U.S. military first sought to win hearts and minds, first faced IEDs in the form of mines buried in roads, first gave up on distinguishing combatants from noncombatants, first began widely and officially (in the Lieber Code) claiming that greater cruelty was actually kindness as it would end the war more quickly, and first defended itself against charges of war crimes using language that it (the North) found entirely convincing but its victims (the South) found depraved and sociopathic. Sherman employed collective punishment and the assaults on morale that we think of as “shock and awe.” Sherman’s assurances to the Mayor of Atlanta that he meant well and was justified in all he did convinced the North but not the South. U.S. explanations of the destruction of Iraq persuade Americans and nobody else.

Sherman believed that his nastiness would turn the South against war. “Thousands of people may perish,” he said, “but they now realize that war means something else than vain glory and boasting. If Peace ever falls to their lot they will never again invite War.” Some imagine this to be the impact the U.S. military is having on foreign nations today. But have Iraqis grown more peaceful? Does the U.S. South lead the way in peace activism? When Sherman raided homes and his troops employed “enhanced interrogations” — sometimes to the point of death, sometimes stopping short — the victims were people long gone from the earth, but people we may be able to “recognize” as people. Can that perhaps help us achieve the same mental feat with the current residents of Western Asia? The U.S. South remains full of monuments to Confederate soldiers. Is an Iraq that celebrates today’s resisters 150 years from now what anyone wants?

Sherman believed that his nastiness would turn the South against war. “Thousands of people may perish,” he said, “but they now realize that war means something else than vain glory and boasting. If Peace ever falls to their lot they will never again invite War.” Some imagine this to be the impact the U.S. military is having on foreign nations today. But have Iraqis grown more peaceful? Does the U.S. South lead the way in peace activism? When Sherman raided homes and his troops employed “enhanced interrogations” — sometimes to the point of death, sometimes stopping short — the victims were people long gone from the earth, but people we may be able to “recognize” as people. Can that perhaps help us achieve the same mental feat with the current residents of Western Asia? The U.S. South remains full of monuments to Confederate soldiers. Is an Iraq that celebrates today’s resisters 150 years from now what anyone wants?

When the U.S. military was burning Japanese cities to the ground it was an editor of the Atlanta Constitution who, quoted by Carr, wrote “If it is necessary, however, that the cities of Japan are, one by one, burned to black ashes, that we can, and will, do.” Robert McNamara said that General Curtis LeMay thought about what he was doing in the same terms as Sherman. Sherman’s claim that war is simply hell and cannot be civilized was then and has been ever since used to justify greater cruelty, even while hiding within it a deep truth: that the civilized decision would be to abolish war.

The United States now kills with drones, including killing U.S. citizens, including killing children, including killing U.S. citizen children. It has not perhaps attacked its own citizens in this way since the days of Sherman. Is it time perhaps for the South to rise again, not in revenge but in understanding, to join the side of the victims and say no to any more attacks on families in their homes, and no therefore to any more of what war has become?

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg