Philosophical Roots and Biological Consequences

Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele contains a comprehensive survey of the philosophical literature that relates to "biocentric" concerns, and in these pages Klages closely scrutinizes the troubled seas and fog-shrouded moorlands of philosophy, both ancient and modern, over which we, unfortunately, have only sufficient time to cast a superficial and fleeting glance. We will, however, spend a profitable moment or two on several issues that Klages examined in some detail, for various pivotal disputes that have preoccupied the minds of gifted thinkers from the pre-Socratics down to Nietzsche were also of pre-eminent significance for Klages.

One of the pre-Socratic thinkers in particular, Heraclitus of Ephesus (c. 536-470 B.C.E.), the "dark one," was looked upon by Ludwig Klages as the founding father of "biocentric," or life-centered, philosophy. Klages and Heraclitus share the conviction that life is ceaseless change, chaos, "eternal flux" [panta rhei]. Both thinkers held that it is not matter that endures through the ceaseless patterns of world-transformation: it is this ceaseless transformation itself that is the enduring process, which alone constitutes this ever-shifting vibrancy, this soaring and fading of appearances, this becoming and passing away of phenomenal images upon which Klages bestowed the name life. Likewise, Klages and Heraclitus were in complete accord in their conviction that natural events transpire in a succession of rhythmical pulsations. For both thinkers, nothing abides without change in the human world, and in the cosmos at large, everything flows and changes in the rhythmical and kaleidoscopic dance that is the cosmic process. We cannot say of a thing: "it is"; we can only say that a thing "comes to be" and that it "passes away." The only element, in fact, in the metaphysics of Heraclitus that will be repudiated by Klages is the great pre-Socratic master’s positing of a "Logos," or indwelling principle of order, and this slight disagreement is ultimately a trivial matter, for the Logos is an item which, in any case, plays a role so exiguous in the Heraclitean scheme as to render the notion, for all practical and theoretical purposes, nugatory as far as the basic thrust of the philosophy of the eternal flux.

Another great Greek philosopher, Protagoras of Abdera (c. 480-410 B.C.E.), is fulsomely acclaimed by Klages as the "father of European psychology and history’s pioneer epistemologist." When Protagoras asserted that the content of perception from moment to moment is the result of the fusion of an external event (the world) with an inner event (the experiencing soul), he was, in effect, introducing the Heraclitean flux into the sphere of the soul. No subsequent psychologist has achieved a greater theoretical triumph. The key text upon which Klages bases this endorsement is Sext. Emp., Pyrrh. I (217): "…matter is in flux, and as it flows additions are made continuously in the place of the effluxions, and the senses are transformed and altered according to the times of life and to all the other conditions of the bodies." (218) "Men apprehend different things at different times owing to their differing dispositions; for he who is in a natural state apprehends those things subsisting in matter which are able to appear to those in a natural state, and those who are in a non-natural state the things which can appear to those in a non-natural state." Thus, the entire sphere of psychical life is a matter of perception, which comprises the act of perception (in the soul) and the content of perception (in the object). This Protagorean insight forms the basis for the distinction between noumenon and phenomenon that will exert such a fructifying influence on Western thought, especially during the period of German Romanticism.

Greek thought has a significant bearing on crucial discoveries that were made by Klages. We have learned that there are two forces that are primordially opposed to each other, spirit and life; in addition, we have seen these forces cannot be reduced to each other, nor can they be reduced to any third term; body and soul constitute the poles of unified life, and it is the mission of spirit to invade that unity, to function as a divisive wedge in order to tear the soul from the body and the body from the soul. Thus, spirit begins its career as the disrupter of life; only at the end of history will it become the destroyer of life. We find a piquant irony in the oft-expressed view that accuses Klages of inventing this "spirit" out of whole cloth, for those who have sneered at his account of the provenance of spirit as a force that enters life from outside the sphere of life, dismissing the very idea from serious consideration by reducing the concept to a caricature ("Klagesian devil," "Klages with his spirit-as-‘space-invader’," and so on), offer quite an irresistible opening for a controversialist’s unbuttoned foil, because such statements reveal, at one and the same time, an ignorance of the history of philosophy in our professors and commentators that should curdle the blood of the most trusting students, as well as an almost incomprehensible inability, or unwillingness, to understand a scrupulously exact and closely-argued text. This intellectual disability possesses, one must confess, a certain undeniable pathos. As it happens, the question as to the provenance of spirit has always enjoyed a prominent position in the history of philosophical speculation (especially in the narrow field of epistemology, i.e., the "theory of cognition"), and the Klagesian viewpoint that has been so ignorantly and persistently excoriated is explicitly drawn from the philosophy of—Aristotle! It was Aristotle, "the master of those who know," who, in discussing the divided substance of man, discovered that he could only account for the origin of one of the components, viz., spirit [Gk. nous], by concluding that spirit had entered man "from outside"! Likewise, the idea of a "tripartite" structure of man, which seems so bizarre to novice students of biocentrism, has quite a respectable pedigree, for, once again, it was Aristotle who viewed man as having three aspects, viz., Psyche-Soma-Nous (Soul-Body-Spirit).

The speculations of the Greek philosophers who belonged to the Eleatic School provided the crucial insights that inspired Klages’s masterful formulation of the doctrine of the "actuality of the images." The specific problem that so exercised the Eleatics was the paradox of motion. The Eleatics insisted that motion was inconceivable, and they proceeded from that paradoxical belief to the conclusion that all change is impossible. One of the Eleatics, Zeno, is familiar to students of the history of philosophy as the designer of the renowned "Zeno’s Paradoxes," the most famous of which is the problem of Achilles and the Tortoise. Zeno provided four proofs against the possibility of motion: 1) a body must traverse in finite time an infinite number of spaces and, therefore, it can never ever begin its journey; 2) here we have Zeno’s application of his motion-theory to the "Achilles" problem that we’ve just mentioned—if Achilles grants a lead or "head start" (analogous to a "handicap") to the tortoise against whom he is competing in a foot-race, he will never be able to overtake the tortoise, because by the time Achilles has reached point A (the starting-point for the tortoise), his opponent has already reached point B. In fact, Achilles will never even reach point A, because before he can traverse the entire distance between his starting-point and point A, he must necessarily cover one-half of that distance, and then one-half of the remaining distance, and so on and so on ad infinitum, as it were! 3) the arrow that has just been launched by the archer is always resting, since it always occupies the same space; and 4) equivalent distances must, at equivalent velocity, be covered in the identical time. But a moving body will pass another body that is moving in the opposite direction (at the identical velocity) twice as quickly as when this body is resting, and this demonstrates that the observed facts contradict the laws of motion. Betraying a certain nervousness, historians of philosophy usually dismiss the Eleatics as superficial skeptics or confused souls, but they never condescend to provide a convincing refutation of their "obvious" or "superficial" errors.

Klages, on the other hand, finds both truth and error in the Eleatics’ position. From the standpoint of an analysis of things, the Eleatics’ are on firm ground in their insistence on the impossibility of change, but from the standpoint of an analysis of appearances, their position is utterly false. Their error arose from the fact that the Greeks of this period had already succumbed to the doctrine that the world of appearances is a world of deception, a reservoir of illusory images. This notion has governed almost every metaphysical system that has been devised by western philosophers down to our own time, and with every passing age, the emphasis upon the world of the things (Noumena) has increased at the expense of the world of appearances (Phenomena). Klages, on the other hand, will solve the "Problem of the Eleatics" by an emphatic demonstration that the phenomenal images are, in fact, the only realities.

During the Renaissance, in fact, when ominous temblors were heralding the dawn of our "philosophy of the mechanistic apocalypse," there were independent scholars (among whom we find Giordano Bruno and Paracelsus) who speculated at length on the relationship that exists between the macrocosm and the microcosm, as well as on the three-fold nature of man and on the proto-characterological doctrine of the "Temperaments."

But the key figure in the overturning of the triadic world-view is undoubtedly the French thinker and mathematician René Descartes (1596-1650), who is chiefly responsible for devising the influential schematic dualism of thinking substance and extended substance, which has dominated, in its various incarnations and permutations, the thinking of the vast majority of European thinkers ever since. Descartes explicitly insists that all of our perceptions as well as every "thing" that we encounter must be reduced to the status of a machine; in fact, he even suggests that the whole universe is merely a vast mechanism (terram totumque hunc mundum instar machinæ descripsi). It is no accident, then, that Cartesian thought is devoid of genuine psychology, for, as he says in the Discours de la méthode, man is a mere machine, and his every thought and every movement can be accounted for by means of a purely mechanical explanation.

Nevertheless, there have been several revolts against Cartesian dualism. As recently as two centuries ago, the extraordinarily gifted group of "Nature Philosophers" who were active during the glory days of German Romanticism, pondered the question of the "three-fold" in publications that can be consulted with some profit even today.

We have seen that the specifically Klagesian "triad" comprises body-soul-spirit, and the biocentric theory holds that life, which comprises the poles of body and soul, occurs as processes and events. Spirit is an intruder into the sphere of life, an invader seeking always to sever the poles, a dæmonic willfulness that is characterized by manic activity and purposeful deeds. "The body is the manifestation of the soul, and the soul is the meaning of the living body." We have seen that Klages was able to trace proleptic glimpses of this biocentric theory of the soul back to Greek antiquity, and he endeavored for many years to examine the residues of psychical life that survive in the language, poetry, and mythology of the ancient world, in order to interpret the true meanings of life as it had been expressed in the word, cult, and social life of the ancients. He brilliantly clarifies the symbolic language of myth, especially with reference to the cosmogonic Eros and the Orphic Mysteries. He also explores the sensual-imagistic thought of the ancients as the foundation upon which objective cognition is first erected, for it is among the Greeks, and only among the Greeks, that philosophy proper was discovered. During the peak years of the philosophical activity of the Greek thinkers, spirit still serves the interests of life, existing in an authentic relationship with an actuality that is sensuously and inwardly "en-souled" [beseelt]. The cosmological speculation of antiquity reveals a profound depth of feeling for the living cosmos, and likewise demonstrates the presence of the intimate bonds that connect man to the natural world; contemplation is still intimately bound-up with the primordial, elemental powers. Klages calls this "archaic" Greek view of the world, along with its later reincarnations in the history of western thought, the "biocentric" philosophy, and he situates this mode of contemplation as the enemy of the "logocentric" variety, i.e., the philosophy that is centered upon the Logos, or "mind," for mind is the manifestation of spirit as it enters western thought with the appearance of Socrates. From Plato himself, through his "neo-Platonic" disciples of the Hellenistic and Roman phases of antiquity, and down to the impoverished Socratic epigones among the shallow "rationalists" of 17th and 18th century Europe, all philosophers who attempt to restore or renew the project of a philosophical "enlightenment," are the heirs of Socrates, for it was Socrates who first made human reason the measure of all things. Socratic rationalism also gave rise to life-alien ethical schemes based upon a de-natured creature, viz., man-as-such. This pure spirit, this distilled ego, seeks to sever all natural and racial bonds, and as a result, "man" prides himself upon being utterly devoid of nobility, beauty, blood, and honor. In the course of time, he will attach his fortunes to the even more lethal spiritual plague known as Christianity, which hides its destructive force behind the hypocritical demand that we "love one’s neighbors." From 1789 onwards, a particularly noxious residue of this Christian injunction, the undifferentiating respect for the ghost known as "humanity," will be considered the hallmark of every moral being.

The heirs of the Socratic tradition have experienced numerous instances of factional strife and re-groupings in the course of time, although the allegiance to spirit has always remained unquestioned by all of the disputants. One faction may call itself "idealistic" because it considers concepts, ideas, and categories to be the only true realities; another faction may call itself "materialistic" because it views "things" as the ultimate constituents of reality; nevertheless, both philosophical factions give their allegiance, nolentes volentes, to the spirit and its demands. Logocentric thought, in fact, is the engine driving the development of the applied science that now rules the world. And by their gifts shall ye know them!

The bitterly antagonistic attitude of Klages towards one of the most illustrious heirs of Socrates, viz., Immanuel Kant, has disturbed many students of German thought who see something perverse and disingenuous in this opposition to the man whom they regard uncritically as the unsurpassed master of German thought. Alfred Rosenberg and the other offical spokesmen of the National Socialist movement were especially enraged by the ceaseless attacks on Kant by Klages and his disciple Werner Deubel. Nevertheless, Kant’s pre-eminence as an epistemologist was disputed as long ago as 1811, when Gottlob Ernst Schulze published his "Critique of Theoretical Philosophy," which was then, and remains today, the definitive savaging of Kant’s system. Klages endorses Schulze’s demonstration that Kant’s equation: actuality = being = concept = thing = appearance (or phenomenon) is utterly false, and is the main source of Kant’s inability to distinguish between perception and representation. Klages adds that he finds it astonishing that Kant should have been able to convince himself that he had found the ultimate ground of the faculty of cognition in—cognition! Klages cites with approval Nietzsche’s "Beyond Good and Evil," in which Kant is ridiculed for attempting to ground his epistemology in the "faculty of a faculty"! Klages shows that the foundation of the faculty of cognition lies not in cognition itself, but in experience, and that the actuality of space and time cannot have its origins in conceptual thought, but solely in the vital event. There can be no experienced colors or sounds without concomitant spatio-temporal characteristics, for there can be no divorce between actual space and actual time. We can have no experience of actual space without sensory input, just as we have no access to actual time without thereby participating in the ceaseless transformation of the phenomenal images.

Formalistic science and its offspring, advanced technology, can gain access to only a small segment of the living world and its processes. Only the symbol has the power to penetrate all the levels of actuality, and of paramount importance to Klages in his elaborate expositions of the biocentric metaphysics is the distinction between conceptual and symbolic thought. We have previously drawn attention to the fact that drive-impulses are manifest in expressive movements that are, in turn, impelled by the influence of a non-conceptual power that Klages calls the symbol. Likewise, symbolic thinking is a tool that may profitably be utilized in the search for truth, and Klages contrasts symbolic contemplation with the logical, or "formalistic," cognition, but he is at pains to draw our attention to the errors into which an unwarranted, one-sided allegiance to either type of thought can plunge us. Although Klages has been repeatedly and bitterly accused by Marxists and other "progressives" as being a vitriolic enemy of reason, whose "irrationalism" provided the "fascists" with their heaviest ideological artillery, nothing could be further from the truth. On occasions too numerous to inventory, he ridicules people like Bergson and Keyserling who believe that "intuition" lights the royal road to truth. His demolition of the Bergsonian notion of the élan vital is definitive and shattering, and his insistence that such an entity is a mere pseudo-explanation is irrefutable and might have been published in a British philosophical journal. In the end, Klages says, "irrationalism" is the spawn of—spirit!

Our ability to formulate and utilize concepts as well as our capacity to recognize conceptual identities is sharply opposed to the procedure involved in the symbolic recognition of identities. The recognition of such conceptual identities has, of course, a crucial bearing on the life of the mind, since it is this very ability that functions as the most important methodological tool employed by every researcher involved in the hard sciences. Symbolic identification, on the other hand, differs widely from its conceptual counterpart in that the symbolic type derives its meaning-content from the "elemental similarity of images." Thus, the process of substantive, or conceptual, identification confronts its opposite number in the "identity of essence" of symbolic thought. It is this "identity of essence," as it happens, which has given birth to language and its capacity to embody authentic meaning-content in words. Jean Paul was quite right, Klages tells us, in describing language as a "dictionary of faded metaphors," for every abstraction that is capable of verbal representation arose from the essentiality of the meaning-content of words.

He draws a sharp distinction between the true symbol (Gk. symbolon, i.e., token) and the mere sign whose significance is purely referential. The true meaning of an object resides in its presence, which Klages refers to as an aura, and this aura is directly communicated to a sensory apparatus that resists all purely linguistic attempts to establish formulas of equivalence or "correspondence." The sensual imagination participates in an unmediated actuality, and intuitive insight (Schauung) allows us to gain access to a realm of symbols, which rush into our souls as divine epiphanies.

Life resists rules, for life is eternal flux. Life is not rigid being, and therefore life will always evade the man-traps of mind, the chains of the concept. Life, comprising the poles of body and soul, is the physical event as phenomenal expression of the soul. There can be no soul-less phenomena and there can be no souls without (phenomenal) appearances, just as there can be no word-less concepts and no words without meaning-content. The physical world is the image-laden appearance (phenomenon) that manifests a psychical substance. When the dæmonic object encounters the receptive, or "pathic," soul, the object becomes a symbol and acquires a "nimbus," which is a pulsating radiance surrounding the moment of becoming. This nimbus is referred to as an "aura" when applied to persons, and both nimbus and aura represent the contribution of the object to the act of perception.

Non-symbolic, formalistic thought, on the other hand is irreverent, non- contemplative, and can best be characterized as an act that is enacted in the service of spirit, which imperiously and reductively ordains that the act of perception must also be an act of the will. Thus the will attains primacy even over the de-substantialized intellect, and Klages—who has persistently been dismissed as an obscurantist and irrationalist—never misses an opportunity to re-iterate his deep conviction that the essence of spirit is to be located in the will and not in the intellect.

As we’ve seen, Klages holds that the living soul is the antithesis of the spirit. The spirit seeks to rigidify the eternal flux of becoming, just as the soul, in yielding passively to the eternal flux, resists the raging Heracleic spirit and its murderous projects. Body and soul reach the peak of creative vitality when their poles are in equipoise or perfect balance, and the high point of life is reached in the experience of sensuous joy. Spirit’s assault upon the body is launched against this joy, and in waging war against the joy of the body, spirit also wages war against the soul, in order to expel the soul, to make it homeless, in order to annihilate all ecstasy and creativity. Every attempt that has been made by monistic thinkers to derive the assault on life from the sphere of life itself has misfired. Such troublesome anomalies as the supernatural visions and cases of dæmonic possession that transpired during the Middle Ages, as well the crippling cases of hysteria so familiar to psychologists in our own time, can never be satisfactorily explained unless we realize that the souls of these unfortunates were sundered by the acosmic force of spirit, whose very essence is the will, that enemy and murderer of life. The conceptual "Tower of Babylon" reared by monists in their ludicrous efforts to derive the force that wages war against life from life itself is no less absurd than would be the foredoomed attempt of a firefighter to extinguish a blaze by converting a portion of the fire into the water that will extinguish the fire!

There is, however, one privileged example of a manifestation of the will in the service of life, and this occurs when the will is enlisted for the purposes of artistic creation. The will, Klages insists, is incapable of creative force, but when the artist’s intuition has received an image of a god, the will functions "affirmatively" in the destructive assaults of the artist’s chisel upon the marble that is to embody the image of the divinity.

Actuality (the home of the soul) is experienced; being (the home of spirit) is thought. The soul is a passive surrender to the actuality of the appearances. Actuality is an ever-changing process of coming to be and passing away that is experienced as images. Spirit attempts to fix, to make rigid, the web of images that constitutes actuality by means of conceptual thought, whose concrete form is the apparatus of the scientist. Cognition represents identical, unfaltering, timeless being; life is the actuality of experience in time. When one says of time that it "is," as if it were something rigid and identical behind the eternal flux, then time is implicitly stripped of its very essence as that which is "temporal"; it is this temporal essence which is synonymous with becoming and transformation. When one speaks of a thing or a realm that is beyond, i.e., that "transcends," the unmediated, experienced actuality of the living world, one is merely misusing thought in order to introduce a conceptual, existential world in the place of the actual one, which has the inalienable character of transitoriness and temporality.

It is within the "pathic" soul that the categories of space and time originate. Acosmic spirit, on the other hand, invaded the sphere of life from outside the spatio-temporal cosmos. Klages scorns the schemes of philosophical "idealists" who attempt to ground the structures of space and time in some transcendental world. He also distinguishes a biocentric non-rational temporality from "objective" time. Biocentric thought, true to its immanentist ("this-worldly") status, recognizes that the images that pulsate in immanentist time are excluded by their very nature from any participation in objective time, for the images can only live within the instantaneous illumination of privileged moments. Klages savages the platitudes and errors of logocentric thinkers who adhere, with almost manic rigidity, to the conventional scheme of dual-axis temporality. In ordinary logic, time is viewed as radiating from the present (that extension-less hypostasis) backward into time-past and forward into time-to-come: but the whole scheme collapses in a heap as soon as we realize that the future, the "time-to-come," is nothing but a delirious void, a grotesque phantom, a piece of philosophical fiction. Only the past possesses true actuality; only the past is real. The future is merely a pale hallucination flitting about in deluded minds. True time is the relationship that binds the poles of past and present. This union occurs as a rhythmical pulsation that bears the moment’s content into the past, as a new moment is generated, as it were, out of the womb of eternity, that authentic depository of actual time. Time is an unending cycle of metamorphoses utterly unrelated to the processes of "objective" time. True time, cyclical time, is clocked by the moments that intervene between a segment of elapsed time and the time that is undergoing the process of elapsing. Time is the soul of space, just as space is the embodiment of time. Only within actual time can we apprehend the primordial images in their sensuous immediacy. Logic, on the other hand, can only falsify the exchange between living image and receptive soul.

Let us examine the biological—or, more properly, ethological—implications of the doctrine of "primordial images" [Urbilder]. Bear in mind, of course, the crucial distinction that is drawn by Klages between the science of fact (Tatsachenwissenschaft) and the science of appearances (Erscheinungswissenschaft): factual science establishes laws of causality in order to explain, e.g., physiological processes or the laws of gravitation; thus, we say that factual science examines the causes of things. The science of appearances, on the other hand, investigates the actuality of the images, for images are the only enduring realities.

The enduring nature of the image can be seen in the example of the generation of a beech-tree. Suppose a beech-tree sheds its seed upon the forest floor, in which it germinates. Can we say of the mother-tree that it lives within the child? Certainly not! We can chop down the mother tree and burn it to ashes, whilst the offspring continues to prosper. Can we say that the matter of which the old tree was composed survives intact within the younger tree? Again, no: for not an atom of the matter that made up the seed from which the young beech grew exists within it. Likewise, not an atom of the matter of which a man’s body is composed at the age of thirty survives from that same man’s body as it was on his tenth birthday. Now, if it is not the matter of which the organism is composed which endures through the ages, what then is it that so endures? "The one possible answer is: an image." Life and its processes occur outside the world of things. On the contrary: life comprises the events in the world of the images.

Thus, we see that the doctrine of the "actuality of the images" [Wirklichkeit der Bilder] holds that it is not things, but images, that are "en-souled" [beseelt], and this proposition, Klages tells us, forms the "key to his whole doctrine of life [Lebenslehre]." Things stand in a closed chain of causality, and there is no reciprocal action between the image and the thing, no parallelism, and no connection, and the attempts that have been undertaken by various philosophers to equate the thing and the image merely serve to rupture the chain of causality in its relevant sphere, i.e., the quantitative scientific method. The receptive soul is turned towards the actuality of the image, and when we say on one occasion that an object is "red," and on another that this same object is "warm," in the first case the reference is to the reality of things, whereas in the second case the reference is to the actuality of images. By using the name of a color, we indicate that we are differentiating between the superficial qualities, or surface attributes, of things; when we say that a colored object is "warm" or "cold," on the other hand, we are pointing to the phenomenal "presence" that has been received by the pathic soul. In fact, there are a whole host of common expressions in which this attribution of subjective, psychical states to visible phenomena occurs. We say, for instance, that red is "hot" and that blue is "cold." In the Vom Wesen des Bewusstseins (1921), a treatise on the nature of consciousness, Klages adduces an astonishingly vast inventory of words that are routinely utilized in descriptions of subjective as well as perceptual phenomena. Someone will speak of his a "bitter" feeling of resentment at some slight or injury. The expression that love is "sweet" occurs in almost every language. Likewise, joy is often described as "bright," just as grief or sorrow are often referred to as "dark." We also have "hot" anger (or the familiar variant, the "‘heat’ of the moment").

Images are the charged powers, or natures, that constitute the basis of all phenomena of cosmic and elemental life as well as of cellular, organic life. All that exists participates in the life of the images. Air, fire, earth, and water; rocks, clouds, planets and suns; plant, animal and man: all of these entities are alive and have souls that share in the life of the cosmos. It isn’t matter that constitutes the stuff of reality, for matter perishes; but the image, which remains alive as it wanders through the rhythmically pulsating cosmos, never dies. It changes through the processes of maturation and growth in the organism, and it transforms itself through the millennia in the species. The images alone have life; the images alone have meaning. The souls of those who now live are images that are temporarily wedded to matter, just as the souls of the dead are images that have been released from matter. The souls of the dead revisit us in their actual form in dreams (Wirklichkeitsform der Traumerscheinung), unconstrained by the limitations of material substance. The souls of the dead are not expelled from the world to live on as immortal "spirits" housed in some transcendent "beyond"; they are, instead, dæmonically vital presences, images that come to be, transform themselves, and vanish into the distance within the phenomenal world that is the only truly existing world.

The human soul recalls the material palpability of the archaic images by means of the faculty that Klages calls "recollection," and his view in this regard invites comparison with the Platonic process of "anamnesis." The recollection of which Klages speaks takes place, of course, without the intervention of the will or the projects of the conscious mind. Klages’s examination of "vital recollection" was greatly influenced by the thought of Wilhelm Jordan, a nineteenth century poet and pioneer Darwinist, whose works were first encountered by the young philosopher at the end of that century. In Jordan’s massive didactic poem Andachten, which was published in 1877, the poet espouses a doctrine of the "memory of corporeal matter." This work had such a fructifying influence on the thought of Klages, that we here give some excerpts:

"It is recollection of her own cradle, when the red stinging fly glues grains of sand into a pointed arch as soon as she feels that her eggs have ripened to maturity. It is recollection of her own food during the maggot-state when the anxious mother straddles the caterpillar and drags it for long distances, lays her eggs in it, and locks it in that prison. The larva of the male stag-beetle feels and knows by recollection the length of his antlers, and in the old oak carves out in doubled dimensions the space in which he will undergo metamorphosis. What teaches the father of the air to weave the exact angles of her net by delicate law, and to suspend it from branch to branch with strings, as firm as they are light, according to her seat? Does she instruct her young in this art? No! She takes her motherly duties more lightly. The young are expelled uncared-for from the sac in which the eggs have been laid. But three or four days later the young spider spreads its little nest with equal skill on the fronds of a fern, although it never saw the net in which its mother caught flies. The caterpillar has no eye with which to see how others knit the silken coffins from which they shall rise again. From whence have they acquired all the skill with which they spin so? Wholly from inherited recollection. In man, what he learned during his life puts into the shade the harvest of his ancestors’ labors: this alone blinds him, stupefied by a learner’s pride, to his own wealth of inherited recollections. The recollection of that which has been done a thousand times before by all of his ancestors teaches a new-born child to suck aptly, though still blind. Recollection it is which allows man in his mother’s womb to fly, within the course of a few months, through all the phases of existence through which his ancestors rose long ago. Inherited recollection, and no brute compulsion, leads the habitual path to the goal that has many times been attained; it makes profoundest secrets plain and open, and worthy of admiration what was merely a miracle. Nature makes no free gifts. Her commandment is to gain strength to struggle, and the conqueror’s right is to pass this strength on to his descendants: her means by which the skill is handed down is the memory of corporeal matter."

The primordial images embody the memory of actual objects, which may re-emerge at any moment from the pole of the past to rise up in a rush of immediacy at the pole of the present. This living world of image-laden actuality is the "eternal flux" [panta rhei] of Heraclitus, and its cyclical transformations relate the present moment to the moments that have elapsed, and which will come around again, per sæcula sæculorum.

Thus we see that the cosmos communicates through the magical powers of the symbol, and when we incorporate symbolic imagery into our inmost being, a state of ecstasy supervenes, and the soul’s substance is magically revitalized (as we have already seen, genuine ecstasy reaches its peak when the poet’s "polar touch of a pathic soul" communicates his images in words that bear the meaning of the actual world within them).

When prehistoric man arrives on the stage, he is already experiencing the incipient stages of the fatal shift from sensation to contemplation. Spirit initiates the campaign of destruction: the receptor-activity is fractured into "impression" and "apperception," and it is at this very point that we witness, retrospectively, as it were, the creation of historical man. Before the dawn of historical man, in addition to the motor-processes that man possessed in common with the animal, his soul was turned towards wish-images. With the shift of the poles, i.e., when the sensory "receptor" processes yield power to the motor "effector" processes, we witness the hypertrophic development of the human ego. Klages is scornful of all egoism, and he repeatedly expressed bitter scorn towards all forms of "humanism," for he regards the humanist’s apotheosis of the precious "individual" as a debased kowtowing before a mere conceptual abstraction. The ego is not a man; it is merely a mask.) In the place of psychical wishes, we now have aims. In the ultimate stages of historical development man is exclusively devoted to the achievement of pre-conceived goals, and the vital impulses and wish-images are replaced by the driving forces, or interests.

Man is now almost completely a creature of the will, and we recall that it is the will, and not the intellect, that is the characteristic function of spirit in the Klagesian system. However, we must emphasize that the will is not a creative, originating force. Its sole task is to act upon the bearer of spirit, if we may employ an analogy, in the manner of a rudder that purposively steers a craft in the direction desired by the navigator. In order to perform this regulative function, i.e., in order to transform a vital impulse into purposeful activity, the drive impulse must be inhibited and then directed towards the goal in view.

Now spirit in man is dependent upon the sphere of life as long as it collaborates as an equal partner in the act of perception; but when the will achieves mastery in man, this is merely another expression for the triumph of spirit over the sphere of life. In the fatal shift from life to spirit, contemplative, unconscious feeling is diminished, and rational judgment and the projects of the regulative volition take command. The body’s ultimate divorce from the soul corresponds to the soullessness of modern man whose emotional life has diminished in creative power, just as the gigantic political state-systems have seized total control of the destiny of earth. Spirit is hostile to the demands of life. When consciousness, intellect, and the will to power achieve hegemony over the dæmonic forces of the cosmos, all psychical creativity and all vital expression must perish.

When man is exiled from the realm of passive contemplation, his world is transformed into the empire of will and its projects. Man now abandons the feminine unconscious mode of living and adheres to the masculine conscious mode, just as his affective life turns from bionomic rhythm to rationalized measure, from freedom to servitude, and from an ecstatic life in dreams to the harsh and pitiless glare of daylight wakefulness. No longer will he permit his soul to be absorbed into the elements, where the ego is dissolved and the soul merges itself with immensity in a world wherein the winds of the infinite cosmos rage and roar. He can no longer participate in that Selbsttödung, or self-dissolution, which Novalis once spoke of as the "truly philosophical act and the real beginning of all philosophy." Life, which had been soul and sleep, metamorphoses into the sick world of the fully conscious mind. To borrow another phrase from Novalis (who was one of Klages’s acknowledged masters), man now becomes "a disciple of the Philistine-religion that functions merely as an opiate." (That lapidary phrase, by the way, was crafted long before the birth of the "philosopher" Karl Marx, that minor player on the left-wing of the "Young Hegelians" of the 1840s; many reactionaries in our university philosophy departments still seem to be permanently bogged down in that stagnant morass—yet these old fogies of the spirit insist on accusing Fascists of being the political reactionaries!)

Man finally yields himself utterly to the blandishments of spirit in becoming a fully conscious being. Klages draws attention to the fact that there are in popular parlance two divergent conceptions of the nature of consciousness: the first refers to the inner experience itself; whilst the second refers to the observation of the experience. Klages only concerns himself with consciousness in the second sense of the word. Experiences are by their very nature unconscious and non-purposive. Spiritual activity takes place in a non-temporal moment, as does the act of conscious thought, which is an act of spirit. Experience must never be mistaken for the cognitive awareness of an experience, for as we have said, consciousness is not experience itself, but merely thought about experience. The "receptor" pole of experience is sharply opposed to the "effector" pole, in that the receptive soul receives sensory perceptions: the sense of touch receives the perception of "bodiliness"; the sense of sight receives the images, which are to be understood as pictures that are assimilated to the inner life. Sensation mediates the experience of (physical) closeness, whilst intuition receives the experience of distance. Sensation and intuition comprehend the images of the world. The senses of touch and vision collaborate in sensual experience. One or the other sense may predominate, i.e., an individual’s sense of sight may have a larger share than that of touch in one’s reception of the images (or vice versa), and one receptive process may be in the ascendant at certain times, whilst the other may come to the fore at other times. (In dreams the bodily component of the vital processes, i.e., sensation, sleeps, whilst the intuitive side remains wholly functional. These facts clearly indicate the incorporeality of dream-images as well as the nature of their actuality. Wakefulness is the condition of sensual processes, whilst the dream state is one of pure intuition.)

Pace William James, consciousness and its processes have nothing to do with any putative "stream of consciousness." That viewpoint ignores the fact that the processes that transpire in the conscious mind occur solely as interruptions of vital processes. The activities of consciousness can best be comprehended as momentary, abrupt assaults that are deeply disturbing in their effects on the vital substrata of the body-soul unity.These assaults of consciousness transpire as discrete, rhythmically pulsating "intermittencies" (the destructive nature of spirit’s operations can be readily demonstrated; recall, if you will, how conscious volition can interfere with various bodily states: an intensification of attention may, for instance, induce disturbances in the heart and the circulatory system; painful or onerous thought can easily disrupt the rhythm of one’s breathing; in fact, any number of automatic and semi-automatic somatic functions are vulnerable to spirit’s operations, but the most serious disturbances can be seen to take place, perhaps, when the activity of the will cancels out an ordinary, and necessary, human appetite in the interests of the will. Such "purposes" of the will are invariably hostile to the organism and, in the most extreme cases, an over-attention to the dictates of spirit can indeed eventuate in tragic fatalities such as occur in terminal sufferers from anorexia nervosa).

Whereas the unmolested soul could at one time "live" herself into the elements and images, experiencing their plenitudinous wealth of content in the simultaneous impressions that constitute the immediacy of the image, insurgent spirit now disrupts that immediacy by disabling the soul’s capacity to incorporate the images. In place of that ardent and erotic surrender to the living cosmos that is now lost to the soul, spirit places a satanic empire of willfulness and purposeful striving, a world of those who regard the world’s substance as nothing more than raw material to be devoured and destroyed.

The image cannot be spoken, it must be lived. This is in sharp contradistinction to the status of the thing, which is, in fact, "speakable," as a result of its having been processed by the ministrations of spirit. All of our senses collaborate in the communication of the living images to the soul, and there are specific somatic sites, such as the eyes, mouth, and genitalia, that function as the gates, the "sacred" portals, as it were, through which the vital content of the images is transmitted to the inner life (these somatic sites, especially the genitalia, figure prominently in the cultic rituals that have been enacted by pagan worshipers in every historical period known to us).

An Age of Chaos

In the biocentric phenomenology of Ludwig Klages, the triadic historical development of human consciousness, from the reign of life, through that of thought, to the ultimate empire of the raging will, is reflected in the mythic-symbolic physiognomy which finds expression in the three-stage, "triadic," evolution from "Pelasgian" man—of the upper Neolithic and Bronze Ages of pre-history; through the Promethean—down to the Renaissance; to the Heracleic man—the terminal phase that we now occupy, the age to which two brilliant 20th century philosophers of history, Julius Evola and Savitri Devi, have given the name "Kali Yuga," which in Hinduism is the dark age of chaos and violence that precedes the inauguration of a new "Golden Age," when a fresh cycle of cosmic events dawns in bliss and beauty.

And it is at this perilous juncture that courageous souls must stiffen their sinews and summon up their blood in order to endure the doom that is closing before us like a mailed fist. Readers may find some consolation, however, in our philosopher’s expressions of agnosticism regarding the ultimate destiny of man and earth. Those who confidently predict the end of all life and the ultimate doom of the cosmos are mere swindlers, Klages assures us. Those who cannot successfully predict such mundane trivialities as next season’s fashions in hemlines or the trends in popular music five years down the road can hardly expect to be taken seriously as prophets who can foretell the ultimate fate of the entire universe!

In the end, Ludwig Klages insists that we must never underestimate the resilience of life, for we have no yardstick with which to measure the magnitude of life’s recuperative powers. "All things are in flux." That is all.

* * *

A NOTE ON AUSTRIAN, OR "CLASSICAL," THEORY AS BIOCENTRIC ECONOMICS

ALTHOUGH Ludwig Klages was one of the most rigorous libertarian thinkers in the history of the West, he can scarcely be said to have developed anything like a full-fledged economic theory of a biocentric cast. Nevertheless, his marked and life-long hostility to state-worship of any kind, when conjoined with his withering attitude towards all attempts to interpret living processes by means of formalistic mathematics, are completely consistent with the doctrines of the Austrian Classical School, which was founded at the end of the 19th Century by Carl Menger and Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk. The Austrian School subsequently flourished in America under the Austrian-born Ludwig von Mises and his most brilliant disciple, New York’s own Murray Rothbard, who, in addition to writing the dazzling formal treatise on economic theory entitled "Man, Economy, and State," was a brilliant essayist and gifted teacher.

The lecture entitled "Profit and Loss," which von Mises delivered to the Mont Pelerin Society in September, 1951, seems to proclaim the quintessentially biocentric version of economic theory:

"The average man lacks the imagination to realize that the conditions of life and action are in a continual flux. As he sees it, there is no change in the external objects that constitute his well-being. His world-view is static and stationary. It mirrors a stagnating environment. He knows neither that the past differed from the present nor that there prevails uncertainty about future things... "The imaginary construction of an evenly rotating economy is an indispensable tool of economic thinking. In order to conceive the function of profit and loss, the economist constructs the image of a hypothetical, although unrealizable, state of affairs in which nothing changes, in which tomorrow does not differ at all from today and in which no maladjustments can arise…The wheel turns spontaneously as it were. But the real world in which men live and have to work can never duplicate the hypothetical world of this mental makeshift.

"Now one of the main shortcomings of the mathematical economists is that they deal with this evenly rotating economy—they call it the static state—as if it were something really existing. Prepossessed by the fallacy that economics is to be treated with mathematical methods, they concentrate their efforts upon the anlysis of static states which, of course, allow a description in sets of simultaneous differential equations. But this mathematical treatment virtually avoids any reference to the real problems of economics. It indulges in quite useless mathematical play without adding anything to the comprehension of the problems of human acting and producing. It creates the misunderstanding as if the analysis of static states were the main concern of economics. It confuses a merely ancillary tool of thinking with reality."

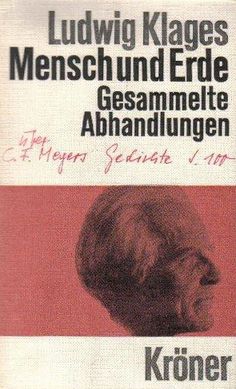

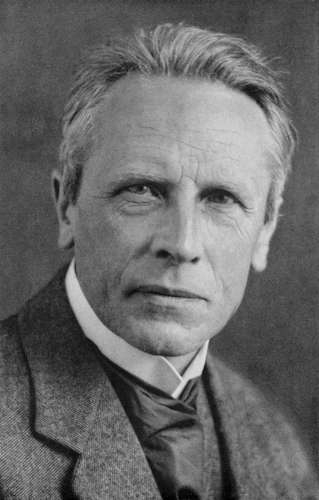

Ludwig Klages est né à Hanovre le 10 décembre 1872. Après des études de physique-chimie, de psychologie et de philosophie, il va fonder en compagnie du sculpteur Hans Busse et Georg Meyer l’Association allemande de graphologie en 1884. Klages sera d’ailleurs mondialement connu pour son travail sur la caractérologie. Son œuvre comporte une part philosophique importante, nourrie de la pensée de Bergson, de Bachofen et de la Lebensphilosophie de Nietzsche. À notre plus grand regret, l’ouvrage capital de Ludwig Klages, Geist als Widersacher der Seele (« L’esprit comme antagoniste de l’âme ») n’est pas pour l’heure disponible en français. Gilbert Merlio nous en résume la ligne directrice dans la préface de l’édition française de Mensch und Erde de Ludwig Klages : « Au logocentrisme triomphant depuis les Lumières, il y oppose son “ biocentrisme ” ou son panvitalisme. Comme tout bon philosophe de la vie, il part de l’opposition entre l’esprit et la vie. Mais il la formule autrement : l’âme est ce qui relie l’homme au macrocosme et lui donne accès à des expériences et des visions archétypales. L’esprit est une conscience de soi “ acosmique ” et au service exclusif d’une volonté qui cherche à façonner la réalité à son image. Comme Spengler au sein de ses “ hautes cultures ”, Klages voit à l’œuvre dans l’histoire une sorte de “ dialectique de la raison ”. Les grandes civilisations naissent de la collaboration de l’âme et de l’esprit. Mais lorsque l’esprit s’émancipe, son action réifiante, qui ne conçoit la nature que comme une matière rationnellement exploitable, coupe l’homme de ses racines cosmiques et devient dangereuse pour l’humanité. C’est ce qui se passe dans la civilisation industrielle moderne (pp. 10-11). »

Ludwig Klages est né à Hanovre le 10 décembre 1872. Après des études de physique-chimie, de psychologie et de philosophie, il va fonder en compagnie du sculpteur Hans Busse et Georg Meyer l’Association allemande de graphologie en 1884. Klages sera d’ailleurs mondialement connu pour son travail sur la caractérologie. Son œuvre comporte une part philosophique importante, nourrie de la pensée de Bergson, de Bachofen et de la Lebensphilosophie de Nietzsche. À notre plus grand regret, l’ouvrage capital de Ludwig Klages, Geist als Widersacher der Seele (« L’esprit comme antagoniste de l’âme ») n’est pas pour l’heure disponible en français. Gilbert Merlio nous en résume la ligne directrice dans la préface de l’édition française de Mensch und Erde de Ludwig Klages : « Au logocentrisme triomphant depuis les Lumières, il y oppose son “ biocentrisme ” ou son panvitalisme. Comme tout bon philosophe de la vie, il part de l’opposition entre l’esprit et la vie. Mais il la formule autrement : l’âme est ce qui relie l’homme au macrocosme et lui donne accès à des expériences et des visions archétypales. L’esprit est une conscience de soi “ acosmique ” et au service exclusif d’une volonté qui cherche à façonner la réalité à son image. Comme Spengler au sein de ses “ hautes cultures ”, Klages voit à l’œuvre dans l’histoire une sorte de “ dialectique de la raison ”. Les grandes civilisations naissent de la collaboration de l’âme et de l’esprit. Mais lorsque l’esprit s’émancipe, son action réifiante, qui ne conçoit la nature que comme une matière rationnellement exploitable, coupe l’homme de ses racines cosmiques et devient dangereuse pour l’humanité. C’est ce qui se passe dans la civilisation industrielle moderne (pp. 10-11). »

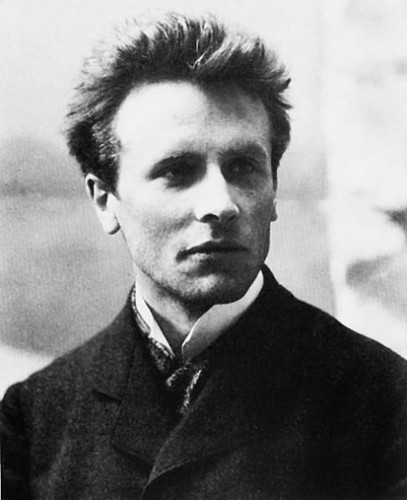

Ludwig Klages was a one-of-a-kind brilliant man who is firstly known for his graphology work. But it is his philosophical work especially which deserves our attention. In fact, Klages belongs to what used to be called Lebensphilopsohie, a term that applies to Nietzsche’s. One thing they share is this dionysiac view on life which is often called « biocentric » when applied to Klages’ philosophy. His anti-christianity is another common point with Friedrich Nietzsche, and the same goes for a genre of paganism, or pantheism, shared by both philosophers.

Ludwig Klages was a one-of-a-kind brilliant man who is firstly known for his graphology work. But it is his philosophical work especially which deserves our attention. In fact, Klages belongs to what used to be called Lebensphilopsohie, a term that applies to Nietzsche’s. One thing they share is this dionysiac view on life which is often called « biocentric » when applied to Klages’ philosophy. His anti-christianity is another common point with Friedrich Nietzsche, and the same goes for a genre of paganism, or pantheism, shared by both philosophers.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Klages does not think highly of most psychology. It is based on misunderstandings, it has limited possibilities to describe personalities, and it is not a science of the soul. This means that modern psychology and older wisdom about the soul are strangers to each other. Klages does connect to such wisdom. Among other things, he is interested in the psychological insights of folk-language. People are “seeing red”, they get “high” or “carried away”, and become “blue”. Klages is interesting to read when he studies this area.

Klages does not think highly of most psychology. It is based on misunderstandings, it has limited possibilities to describe personalities, and it is not a science of the soul. This means that modern psychology and older wisdom about the soul are strangers to each other. Klages does connect to such wisdom. Among other things, he is interested in the psychological insights of folk-language. People are “seeing red”, they get “high” or “carried away”, and become “blue”. Klages is interesting to read when he studies this area.

Klages puts Life in the centre, but he also identifies an anti-Life force that gradually infiltrated the world and took it over.

Klages puts Life in the centre, but he also identifies an anti-Life force that gradually infiltrated the world and took it over.

DURING THE CLOSING YEARS of the 19th century, the limitations and inadequacies of the superficial positivism that had dominated European thought for so many decades were becoming increasingly apparent to critical observers. The wholesale repudiation of metaphysics that Tyndall, Haeckel and Büchner had proclaimed as a liberation from the superstitions and false doctrines that had misled benighted investigators of earlier times, was now seen as having contributed significantly to the bankruptcy of positivism itself. Ironically, a critical examination of the unacknowledged epistemological assumptions of the positivists clearly revealed that not only had Haeckel and his ilk been unsuccessful in their attempt to free themselves from metaphysical presuppositions, but they had, in effect, merely switched their allegiance from the grand systems of speculative metaphysics that had been constructed in previous eras by the Platonists, medieval scholastics, and post-Kantian idealists whom they abominated, in order to adhere to a ludicrous, ersatz metaphysics of whose existence they were completely unaware.

DURING THE CLOSING YEARS of the 19th century, the limitations and inadequacies of the superficial positivism that had dominated European thought for so many decades were becoming increasingly apparent to critical observers. The wholesale repudiation of metaphysics that Tyndall, Haeckel and Büchner had proclaimed as a liberation from the superstitions and false doctrines that had misled benighted investigators of earlier times, was now seen as having contributed significantly to the bankruptcy of positivism itself. Ironically, a critical examination of the unacknowledged epistemological assumptions of the positivists clearly revealed that not only had Haeckel and his ilk been unsuccessful in their attempt to free themselves from metaphysical presuppositions, but they had, in effect, merely switched their allegiance from the grand systems of speculative metaphysics that had been constructed in previous eras by the Platonists, medieval scholastics, and post-Kantian idealists whom they abominated, in order to adhere to a ludicrous, ersatz metaphysics of whose existence they were completely unaware.