Gwendolyn Taunton

Ex: https://sidneytrads.com

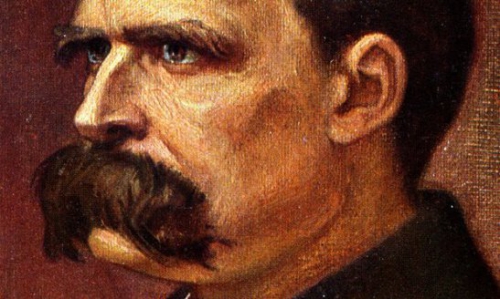

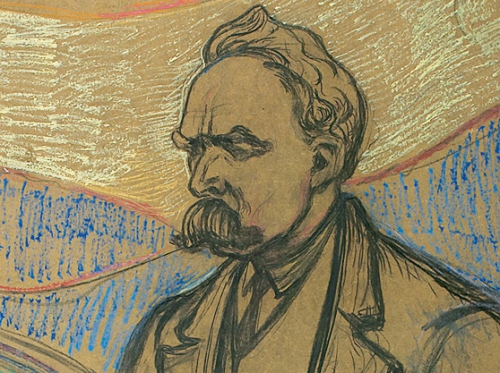

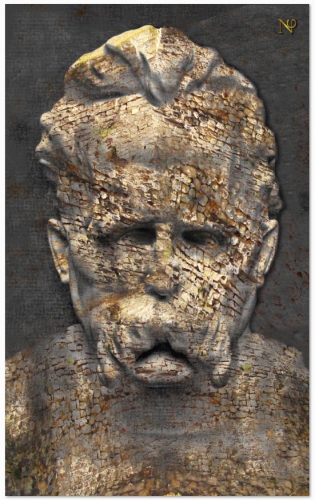

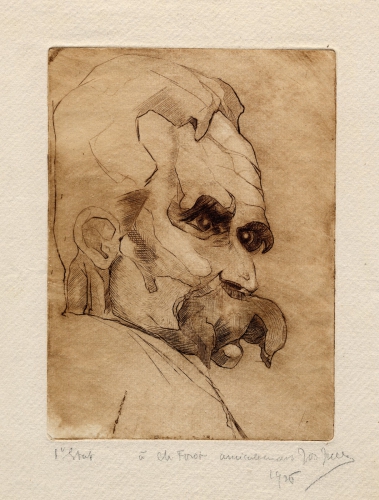

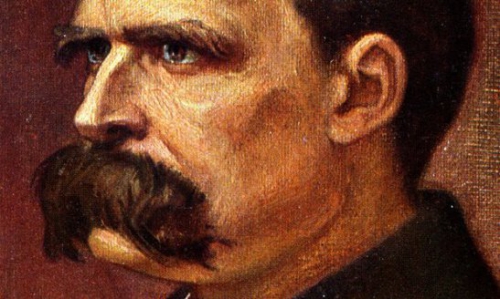

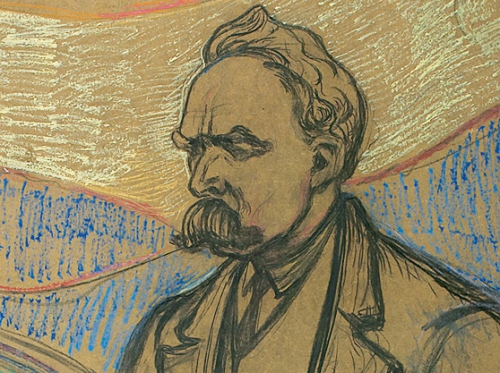

Nietzsche: The Physician of Culture

Do not be afraid of the stream of things: this stream turns back on itself: it runs away from itself not only twice. Every ‘it was’ becomes again an ‘it is.’ The past bites everything future in the tail.

– Friedrich Nietzsche.

During March 1873, Friedrich Nietzsche wrote a letter to Erwin Rohde, telling Rhode that he was thinking of naming a book The Philosopher as the Physician of Culture.1 In regard to this statement there can be little doubt that Nietzsche believed his work would heal some of the ailments afflicting Western culture. On the surface Nietzsche’s work is often deeply critical of both religion and politics, so the cultural impact of his philosophy is not always immediately perceptible. Nonetheless, Nietzsche intended to have an effect which would drastically alter the nature of civilization, and this is why he referred to the philosopher as being the ‘physician of culture’.

Culture provides a mechanism for common interests and objectives that can tie a civilization together. The historical methods of unifying the nation were different – people could easily be united through shared ethnicity, tradition, and religion. In the contemporary West however these techniques are no longer feasible. The ethnic composition of a modern democracy is divided into several nationalities, tradition has been replaced by legislative procedure, and religion abandoned almost entirely. Under such conditions, culture is the most viable tool with which to cultivate national sentiment and communal pride in a civilization.

The idea of culture as a defining characteristic of the nation is not unique to Nietzsche. It is also found in the ideas of Johann Gottfried von Herder who proposed that there was a “popular spirit” or Volksgeist at the core of nationalism.2 What neither Herder nor Nietzsche expected however, was that the creation of cultural works in the West would be severely impaired by a heavily production based ‘worker’ society. This production/worker society is a hybrid of both capitalism and socialism, and has its roots in the revolt of the bourgeoisie, as Nicholas Birns relates here: “The valorization of labor, originally upheld by the bourgeoisie as a reaction to the disinterested and therefore ‘unproductive’ nobility provided the first substitute for identity”.3 As a consequence of this modern democracies, by embracing capitalism and the ‘valorization of the worker’, have created a nation which is no longer capable of generating authentic culture. The necessity of full time employment for both men and women in a capitalist worker/production society, requires that in order to live at even a level of basic subsistence, the prospect of any pursuits capable of generating culture are instantly negated. Achievements in the arts, humanities, or any other academic area capable of creating cultural values, is likewise denigrated to such an extent that even the worker in factory is now held in higher esteem, and those who do attempt to make cultural achievements to further society receive nothing but lowly paid employment in the hospitality industry. The final culmination of this leaves all cultural efforts stillborn, the ramifications of which, though subtle, will one day become deadly as modern society fractures into several opposing groups, none of whom will profess loyalty to the community, nation, or civilization. By abandoning the cultural aspects of the nation, the heart of a civilization corrodes, and entropy spreads slowly to poison the entire political system.

This leaves the modern nation with a very real corundum – what constitutes national identity in a modern multicultural society where tradition and religion have been displaced? And furthermore, can it even be achieved without those who used to create culture, such as the artists and academics in the humanities?

Birns also raises this question when he states that, “Contemporary ‘nationalism’ might well be founded on a political ideal of State and citizenship, it would nevertheless be a mistake to believe that abstract political values are sufficient to create a common identity and, especially that they would suffice to convince their members to accept the sacrifices they sometimes require”.4 Even the very liberal John Stuart Mill, writes that democracy cannot function in a pluralistic society, saying that “Democratic power belongs to the people, but only if the people are united.”5

These questions surrounding culture, community, nation, and even civilization itself therefore have to be based on personal identity, which philosophers such as Heidegger have defined as “Being”. This includes self-awareness of identity as an individual expression of autonomy, as well as the state defined Being. Being is an individual expression of culture, and individual Being is a reflection of the values of the civilization. One cannot profess their loyalty to a government if it is alienated from the community, and as a consequence the community will not make any sacrifices on behalf of the nation, because they have become estranged from the government. A shared identity with the people therefore remains a fundamental factor in the process of ‘good government’ and is the most basic foundation for any genuine attempt to forge a national identity. It is the duty of a government to provide its citizens with a real sense of Being and identity within the community. Culture is not merely the byproduct of a successful nation; it is the mandatory requirement for building a great civilization, and it is equally as necessary for individual Being.

Nietzsche also espouses this sentiment in The Birth of Tragedy where he describes culture as the “most basic foundation of the life of a people”.6 The modern nation however has become increasingly complex and the more it grows, the weaker the ties to the people and the concept of Being in the nation becomes. Familiarity is essential in creating communal bonds, but the very size of the nation renders this difficult, and micro-communities are therefore formed which ultimately serve to de-stabilize the larger power structure of the government. This is not only bad for the nation, but also for those who govern the nation, because it creates a distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’, and this perceived disparity dissolves the foundation of collective identity within the nation. As such, the elected representatives of modern democracies immediately find themselves juxtaposed with a large group of disgruntled citizens who have no true loyalty to the nation, and are instead controlled by purely by legislative force alone. In the worst case scenario, this leads to both ressentiment and revolution.

Nietzsche also espouses this sentiment in The Birth of Tragedy where he describes culture as the “most basic foundation of the life of a people”.6 The modern nation however has become increasingly complex and the more it grows, the weaker the ties to the people and the concept of Being in the nation becomes. Familiarity is essential in creating communal bonds, but the very size of the nation renders this difficult, and micro-communities are therefore formed which ultimately serve to de-stabilize the larger power structure of the government. This is not only bad for the nation, but also for those who govern the nation, because it creates a distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’, and this perceived disparity dissolves the foundation of collective identity within the nation. As such, the elected representatives of modern democracies immediately find themselves juxtaposed with a large group of disgruntled citizens who have no true loyalty to the nation, and are instead controlled by purely by legislative force alone. In the worst case scenario, this leads to both ressentiment and revolution.

Ressentiment is another key concept in Nietzsche’s philosophy. Ressentiment is a form of resentment, arising from envy, where a mass of those who believe themselves to be oppressed attempt to reform the social structure in their own interests, overthrowing those who are identified as the governing elite. As R. Jay Wallace explains, “Ressentiment becomes creative and gives birth to values when the tensions that attend it lead the powerless to adopt and internalize a wholly new evaluative framework.”7 Ressentiment is the mother of all revolutions, and all political powers should err on the side of caution when the chasm between the powerful and the powerless yawns dangerously wide. Therefore, far from endorsing oppressive regimes, Michael Ure informs us that Nietzsche “shares with the Hellenistic schools the belief that the central motivation for philosophizing is the urgency of human suffering and that the goal of philosophy is human flourishing, or eudaimonia”.8

Not only did Nietzsche draw inspiration from Hellenic philosophy, he was also heavily influenced by mythology. It may be difficult to reconcile Nietzsche’s vehement attacks on Christianity with this seemingly incongruous interest in the archaic religions of Greece, but nonetheless Friedrich Nietzsche was uncontestably influenced by Greek mythology. The key to understanding this contradiction in his philosophy can once again be explained by his use of the phrase the “philosopher as the physician of culture”. Nietzsche interprets mythology as a formula of symbols. These are not literal truths, and therefore are not a contradiction in his writing because the symbols found in mythology relate to insights into human behavior and culture. This is because it does not require religious belief. It is in this manner that Nietzsche makes use of Dionysus and Apollo. Tracy B. Strong reiterates this saying that, “Nietzsche’s appeal to the Dionysian does not refer to an attempt to go back to something that lies under Greek life or the origins of that which is Greek but, rather, to more new developments that might serve in the transformation of the older Apollonian world.”9 Dionysus therefore links the old traditions to a new culture envisioned by Nietzsche. Accordingly, myth becomes a powerful weapon for the preservation of culture, because unlike religion, belief in the literal truth of myth is not required, just a concession that it is part of a shared history and a testament to the enduring value of culture, which conveys its experiences from antiquity into modern times. As such, myths become a proclamation of the grandeur of one’s culture and “whatever their own particular political characteristics might have been, all nations have always resorted to national myths”, as Birns tells us.10

Nietzsche’s own use of myth is exceedingly complex and multi-layered, designed with the specific goal of reinvigorating the waning power of culture in the West, in a manner that is not dependent on the whims of political parties or organizations. This begins with his famous Apollonian/Dionysian dyad. The conception of this idea is not purely Nietzsche’s because traces of it can be found in earlier Germanic authors. Interest in these two gods was prolific before Nietzsche for as Max Baeumer remarks,

The tradition of Dionysus and the Dionysian in German literature from Hamann and Herder to Nietzsche — as it has been set forth for the first time from aesthetic manifestoes, from literary works, and from what today are obscure works of natural philosophy and mythology — bears eloquent witness to the natural-mystical and ecstatic stance of German Romanticists which reached its final culmination in the works of Friedrich Nietzsche.11

Other notable influences include J. J. Bachofen and Georg Friedrich Creuzer. Although interested in Creuzer, Nietzsche only mentioned him once in writing, “during his early Basel lectures (1870-71)”.12 Bachofen’s influence is more obvious and his contrast between Apollo and Demeter is an obvious analogy with Nietzsche’s own Apollo/Dionysus. Changing Demeter to Dionysus was a deliberate correction on Nietzsche’s part, because Hellenic myths and rituals from Delphi indicate that the two gods were often worshipped in tandem, with one as the mirror of the other. Thus, to Nietzsche and the Hellenes, Bachofen’s opposition of the Sun/Sky/Male to Lunar/Earth/Female was discounted as a false dichotomy – instead the interpretation was more complex – it occurred between two solar male gods connected with the creative process of higher cognition.

The most obvious figure to study in relation to this is Orpheus, who is related to both Dionysus and Apollo, and despite his tragic end, represents the balance of the two creative drives in Man. Kocku von Stuckrad tells us that, “Orpheus is truly a reconciler of opposites: he is the fusion of the radiant solar enlightenment of Apollo and the somber subterranean knowledge of Dionysus”.13 Nietzsche’s Dionysus is also a reconciler of opposites, who absorbs the characteristics of his counter-part Apollo into himself, in order to establish form from his own state of natural formlessness, becoming whole when the two creative drives merge into one. Von Stuckrad also makes it clear that Apollo does not disappear from Nietzsche’s work, but is instead merged with Dionysus: “Apollo, it is true, more and more loses his name to the other god, but by no means the power of his artistic creativeness, forever articulating but the Dionysian chaos in distinct shapes, sounds and images, which are Dionysian only because they are still aglow with the heat of the primeval fire”.14 Dionysus and Apollo are amalgamated into a mythical whole called “Dionysus” which is a synthesis of the two gods in Nietzsche’s philosophy. Thus when Nietzsche writes,

Indeed, my friends, believe with me in this Dionysiac life and in the rebirth of tragedy! Socratic man has run his course; crown your head with ivy, seize the thyrsus, and do not be surprised if tiger and panther lie down and caress your feet! Dare to lead the life of tragic man, and you will be redeemed. It has fallen to your lot to lead the Dionysiac procession out of India to Greece. Gird yourselves for a severe conflict, but have faith in the thaumaturgy of your god!15

Nietzsche does not proclaim the literal resurrection of a deity or religion, but instead the rebirth of the creative power inherent in Man. It is the rebirth of myth deployed to drive culture, announced by the artist/philosopher who operates as the ‘physician of culture’. Furthermore, the exemplification of the “tragic artist” is implicitly reliant on Dionysus and ancient Hellenic myth. Strong states that,

The process of the tragic chorus is the dramatic proto-phenomenon: to see oneself [as embodied in the chorus] transformed before one’s very eyes [as member of the audience] and to begin to act as if one had actually entered into another body, another character. It is thus, he argues, that tragedy effects a cultural transformation in the citizenry-spectators. A potential subtitle to BT [Birth of Tragedy] from fall 1870 reads “Considerations on the ethical-political significance of musical drama”.16

In regards to music and its effect on politics and culture, another figure connected to Nietzsche who cannot be ignored is the ever-present specter of Richard Wagner. Ultimately the friendship of the two was not based purely on passion for music, but also the use of mythology, something with Richard Wagner indisputably drew upon in his operas. Wagner wrote in Deutsche Kunst and Deutsche Politik on the social and political meaning of such aesthetic theories: “Modern life, Wagner wrote, [shall be] reorganized by the rebirth of art, and especially by a new theater whose life-giving function shall be equal to that of ancient Greek drama”.17 Although Nietzsche would eventually separate himself from Wagner due to the musician’s anti-Semitism, Nietzsche also explored the uses of myth during his period of friendship with Wagner. “The legend of Prometheus”, Nietzsche writes,

In regards to music and its effect on politics and culture, another figure connected to Nietzsche who cannot be ignored is the ever-present specter of Richard Wagner. Ultimately the friendship of the two was not based purely on passion for music, but also the use of mythology, something with Richard Wagner indisputably drew upon in his operas. Wagner wrote in Deutsche Kunst and Deutsche Politik on the social and political meaning of such aesthetic theories: “Modern life, Wagner wrote, [shall be] reorganized by the rebirth of art, and especially by a new theater whose life-giving function shall be equal to that of ancient Greek drama”.17 Although Nietzsche would eventually separate himself from Wagner due to the musician’s anti-Semitism, Nietzsche also explored the uses of myth during his period of friendship with Wagner. “The legend of Prometheus”, Nietzsche writes,

is indigenous to the entire community of Aryan races and attests to their prevailing talent for profound and tragic vision. In fact, it is not improbable that this myth has the same characteristic importance for the Aryan mind as the myth of the Fall has for the Semitic, and that the two myths are related as brother and sister.18

Ultimately this line of thought would end for Nietzsche once the National Socialist movement began to arise in Germany, terminating not only Nietzsche’s research in this area, but also his friendship with Wagner. Ultimately, Wagner’s manipulation of myth via music achieved a devastating impact over Germany, and the power he exerted over the country through his music was significant. Although Nietzsche passionately disagreed with Wagner’s anti-Semitism, he still believed culture would be the driving impetus behind any political change. Nietzsche simply could not accept the vision of culture that Wagner desired and opted to create his own instead.

Aside from revitalizing national spirit though mythology to create national identity, there is another option for generating culture which relates to Nietzsche – geophilosophy. According to Deleuze and Guattari, geophilosophy recognizes that thinking goes on not between subject and object but, rather, “takes place in the relationship of territory and the earth.”19 It therefore ties man to the ultimate national symbol – the landscape which surrounds them. Herman Siemens and Gary Shapiro argue that “Nietzsche’s thought undermines ideologically driven metanarratives of globalization, such as Eduard von Hartmann’s Weltprozess story, repeatedly ridiculed by Nietzsche, and also the more topical “end of history” story popularized by Fukuyama.”20 Haroon Sheikh expands on geophilosophy by connecting geography directly to culture, stating that “the competitive advantage of a country is grounded in its traditional culture”.21 Nietzsche’s “Peoples and Fatherlands […] locates philosophy in a dynamic tension between deterritorialization (as in philosophy’s universalistic claims) and reterritorialization (as in the unavoidable, if largely unconscious reinscription of thought within spatial coordinates)”.22 Likewise, “Deleuze and Guattari see Nietzsche’s notion of the ‘untimely’ (unzeitmässig) — as in Untimely Meditations — to involve the opening of a geographic rather than a historical perspective”.23 This paves the way for a spatial developmental theory of philosophy instead of temporal one. The temporal aspect is manifest in the idea of Eternal Recurrence – everything repeats save that which is constant – as such they earth itself offers a ‘firm foundation’ for philosophy, compared to the fickle whims of history, which is one of the reasons they are “untimely”.

Leo Strauss and Francis Fukuyama take another view on culture in regards to Nietzsche’s concept of the Last Man, and seek to interpret Nietzsche in terms of the classical tradition of political theory, “which they oppose to modern political theory that sought to banish the concept of thymos from political thought”.24 Thymos is a part of the soul mentioned by Plato which deals with the human drive for recognition and honor. Fukuyama in particular interprets Nietzsche’s theories that culminate in the idea of the Last Man as a theory of the decline of thymos in the modern world.25 This highlights the connection between Nietzsche and Hellenic ideas yet again. Sheikh also believes that Fukuyama agrees with the “idea of the decline of thymos” saying that, “Due to the end of struggle and the pacification of man, the powerful and violent types like Caesar and Alexander but also the great creative types—artists and writers such as Homer, Michelangelo, or Pascal—can no longer come into existence”.26 However, links to the world of tradition still remain because,

The modern economy is driven by motives other than the purely material pursuit of comfort. In new forms, ancient authorities still command respect and motivate people, infusing the modern world with traditional thymos. Moreover, Fukuyama argues, these are not simple remnants of the past set to disappear in the future but, instead, critically underpin the modern world because they determine, for instance, the success societies have in terms of innovation and economies of scale.27

It is with this in mind that Nietzsche proposes Grosse Politik (Grand Politics) which is to be fought at an ideological and cultural level via a war he terms as the Geisterkrieg.

I bring the war. Not between people and people […] Not between classes […] I bring the war that goes through all absurd circumstance of people, class, race, occupation, upbringing, education: a war like that between rise and decline, between will to live and vengefulness against life.28

This is Nietzshe’s Geisterkrieg – a war of ideas that is to fought at the academic and intellectual level to control the flow of ideas, culture, and the politics that emerge from it. This is similar to the modern idea of “metapolitics”. The Geisterkrieg however, “cuts right through the absurd arbitrariness that are peoples, class, race, profession, education, culture,” a war instead “between ascending and declining, between will-to-live and the desire for revenge on life”.29 In the context of the Geisterkrieg and Grosse Politik, the artists and the philosophers become the creators of all future governments and orders – for as Nietzsche tells us, “The artist and philosopher […] strike only a few and should strike all”.30 This means that they have not yet realized their ability to create cultural changes. Only the artists and philosophers are capable of launching Nietzsche’s Geisterkrieg, the war of ideas. However, due to the current dominance of capitalism and production based society over democracy (across both the Left and Right) the influence of artists and philosophers are severely impaired. And because of this, their rule continues unchallenged because Nietzsche’s Geisterkrieg, if successful, would end all petty nationalism and party specific squabbles. Partisan based politics would no longer exist, replaced instead by leaders who embody thymos the most as is stated here,

This is Nietzshe’s Geisterkrieg – a war of ideas that is to fought at the academic and intellectual level to control the flow of ideas, culture, and the politics that emerge from it. This is similar to the modern idea of “metapolitics”. The Geisterkrieg however, “cuts right through the absurd arbitrariness that are peoples, class, race, profession, education, culture,” a war instead “between ascending and declining, between will-to-live and the desire for revenge on life”.29 In the context of the Geisterkrieg and Grosse Politik, the artists and the philosophers become the creators of all future governments and orders – for as Nietzsche tells us, “The artist and philosopher […] strike only a few and should strike all”.30 This means that they have not yet realized their ability to create cultural changes. Only the artists and philosophers are capable of launching Nietzsche’s Geisterkrieg, the war of ideas. However, due to the current dominance of capitalism and production based society over democracy (across both the Left and Right) the influence of artists and philosophers are severely impaired. And because of this, their rule continues unchallenged because Nietzsche’s Geisterkrieg, if successful, would end all petty nationalism and party specific squabbles. Partisan based politics would no longer exist, replaced instead by leaders who embody thymos the most as is stated here,

Nietzsche concludes his “document of great politics” by declaring, “[I]f we are successful, we will have between our hands the government of the earth—and universal peace” (letter to Georg Brandes, beginning of December 1888).31

The Geisterkrieg Nietzsche desires to see is an intellectual and artistic contest, which leads individuals to overcome themselves and thus bring to light the Übermensch, but this is specifically within the rank ordering of the Party of Life (the replacement for the modern political system, which is more akin to a guild of experts).32 It is by no means a physical war. Nothing lasts forever, the rise and fall of empires is eternal – there is no man made legislation that can endure, and ours is no exception. But once an idea or concept successfully endures the ravages of history to become venerable, it passes into tradition and myth – thus making them not mere superstitions, but instead the enduring and strongest feature of any cultural or ancestral heritage.

Cristiano Grottanelli believes that “every culture that has lost myth has lost, by the same token, its natural, healthy creativity”.33 And when a culture loses its creative power, it begins to die. Myth is a link to a shared tradition and community, and it when it is present the nation is more vital, more healthy. According to Ure this is what Nietzsche means when he is, referring to himself as “the physician of culture” Nietzsche’s ambition is to prescribe for the state the medicine which he believes will cause culture to flourish and make the state healthy once again, by utilizing culture as the stimuli for what Heidegger will later call “Being”. In becoming a “physician of culture”, Nietzsche also reveals his own influences that served to create his “Being”, which are largely derivative of his own knowledge of Hellenic philosophy and culture, for,

Like all the Hellenistic philosophers, Nietzsche seems to have arrived at the view that the source of our misery is not to be found in things but in the value judgments that we bring to bear upon things and we can be cured of our ills only through a change in our value judgments.34

In the modern world metaphysical and religious elements are decreasing in popularity. Myth remains useful because it entails only a shared past, and not a shared belief. There is no compulsion or requirement for belief in any religion to accept the cultural significance of a common history. A society which has lost its myth, has lost both his past heritage and its present culture. Cristiano Grottanelli states that as the ‘physician of culture’ Nietzsche sought to create a “mythos of the future”,

In his reconsideration of Nietzsche’s attitude to myth that was published in 1979, Peter Putz (Der Mythos bei Nietzsche) stated that the German philosopher stopped discussing myth as such after Die Ursprung der Tragodie, only to “fashion a myth (the myth of Life).” More recently still, Alan Megill has stated that Nietzsche created “the mythos of the future, the myth destined to save us from the nihilism that he believes has cast its shadow on Western culture.”35

These future myths and possibilities are precisely what he wished to create in order to revive both culture and the nation. By supplying people with new myths (which maintain links with their ancient predecessors) it reinforces culture by unifying individuals in a shared sense of communal society. Citizens must be able to develop a sense of Being within the community, and they must as a primary mandate for this, perceive the government as an ally, not as an enemy. A civilization where the citizens are divided is one where loyalties are divided, for as Birns reminds us,

In medieval societies the prevalent virtue is loyalty. Therefore, the question is not “who am I?” but “to whom am I loyal,” i.e. “to whom do I pledge allegiance?” Identity is the direct result of that allegiance. Society is then divided in groups, which interlock but at the same time remain separate.36

In a society which is composed of many different ethnicities, religions, or cultural groups, such as Australia, a narrative is required to unite all the different components which are part of the nation. Cultural aspects such as national myths and the use of the landscape itself (via geophilosophy) are the only viable means to do so in socially diverse nation. For this Nietzsche prescribes a war of ideas (Geisterkrieg) which competes for intellectual dominance to create what he calls ‘Grand Politics’ (Grosse Politik) which is based not on parties, but on a new form of high nationalism that elevates the country by cultivating culture to set a “new agenda for innovation”. The physician of culture, whilst writing the prescription may not have supplied us with the medicine, but he did provide us with the formula to create our own cure.

– Gwendolyn Taunton was the recipient of the Ashton Wylie Award for Literary Excellence for her first book, Primordial Traditions, a selection of articles from the periodical of the same name which was in operation between 2006 to 2010. The award was presented by the New Zealand Society of Authors and the Mayor of Auckland. The proceeds of the award were used to establish further titles. Both becoming a full time publisher and author, Taunton has worked as the web and graphic designer for the National Centre for Research on Europe and the Delegation of the European Union. Presently she publishes other authors through Numen Books and Manticore Press.

Endnotes:

- Tracy B. Strong, “Nietzsche and the Political – Tyranny, Tragedy, Cultural Revolution, and Democracy” The Journal of Nietzsche Studies, Issue 35/36 (Spring/Autumn 2008) p. 58.

- Nicholas Birns, Ressentiment and Counter-Ressentiment: Nietzsche, Scheler, and the Reaction Against Equality (The Nietzsche Circle, 2005) p. 15.

- Ibid., p.20.

- Ibid., p.22.

- Ibid., p.12.

- Tracy B. Strong, op. cit. p. 48.

- R. Jay Wallace, Ressentiment, Value, and Self-Vindication: Making Sense of Nietzsche’s Slave Revolt (University of California, Lecture Notes, undated) p.13. This document is available as part of the “A Priori – The Erskine Lectures in Philosophy” at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand, Volume 3.

- Michael Ure, “Nietzsche’s Free Spirit Trilogy and Stoic Therapy” The Journal of Nietzsche Studies, Issue 38 (Autumn 2009) p. 62.

- Tracy B. Strong, op. cit. p. 57.

- Nicholas Birns, op. cit. p. 22.

- Kocku von Stuckrad, “Utopian Landscapes and Ecstatic Journeys: Friedrich Nietzsche, Hermann Hesse, and Mircea Eliade on the Terror of Modernity” Numen 57 (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2010) p. 81.

- Robert A. Yelle, “The Rebirth of Myth? Nietzsche’s Eternal Recurrence and its Romantic Antecedents” Numen, No. 47 (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2000) p. 184.

- Kocku von Stuckrad, op. cit. p. 81.

- Ibid., p. 83.

- Cristiano Grottanelli, “Nietzsche and Myth” History of Religions, Vol. 37 No. 1 (August 1997) p. 3.

- Tracy B. Strong, op. cit. p. 57.

- Cristiano Grottanelli, op. cit. p. 3.

- Ibid., p. 1.

- Herman Siemens, “Nietzsche’s Critique of Democracy (1870–1886)” The Journal of Nietzsche Studies, Issue 38 (Autumn 2009) p.11.

- Herman Siemens and Gary Shapiro, “What Does Nietzsche Mean for Contemporary Politics and Political Thought?” The Journal of Nietzsche Studies, Issue 35/36 (Spring/Autumn 2008) p. 4.

- Haroon Sheikh, “Nietzsche and the Neoconservatives: Fukuyama’s Reply to the Last Man” The Journal of Nietzsche Studies, Issue 35/36 (Spring/Autumn 2008) p. 41.

- Herman Siemens and Gary Shapiro (2008) op. cit. p. 4.

- Herman Siemens (2009) op. cit. p. 9.

- Haroon Sheikh, op. cit. p. 29.

- Ibid., p. 29.

- Ibid., p. 35.

- Ibid., p. 42.

- Ibid., p. 33.

- Hugo Halferty Drochon, “The Time Is Coming When We Will Relearn Politics” The Journal of Nietzsche Studies, Issue 39 (Spring 2010) p.73.

- Tracy B. Strong, op. cit. p. 53.

- Hugo Halferty Drochon, op. cit. p. 74.

- Ibid., p. 79.

- Cristiano Grottanelli, op. cit. p. 2.

- Michael Ure, op. cit. p. 72.

- Cristiano Grottanelli, op. cit. p. 8.

- Nicholas Birns, op. cit. p. 15.

Citation Style:

This article is to be cited according to the following convention:

Gwendolyn Taunton, “Nietzsche: The Physician of Culture” SydneyTrads – Weblog of the Sydney Traditionalist Forum (30 April 2016) <sydneytrads.com/2016/04/30/2016-symposium-gwendolyn-taunton> (accessed [date]).

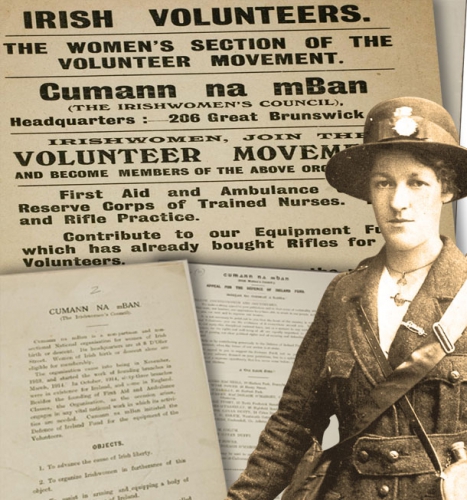

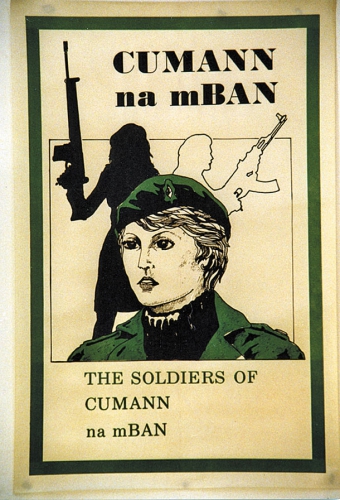

Ce même jour, les Dublinois eurent la surprise de voir 70 femmes armées de fusils pénétrer dans la cité dans un ordre impeccable. Elles savaient toutes ce qui les attendait. Pourtant, elles avançaient sans hésitation. C’était le Cumann na mBan.

Ce même jour, les Dublinois eurent la surprise de voir 70 femmes armées de fusils pénétrer dans la cité dans un ordre impeccable. Elles savaient toutes ce qui les attendait. Pourtant, elles avançaient sans hésitation. C’était le Cumann na mBan.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Nietzsche also espouses this sentiment in The Birth of Tragedy where he describes culture as the “most basic foundation of the life of a people”.6 The modern nation however has become increasingly complex and the more it grows, the weaker the ties to the people and the concept of Being in the nation becomes. Familiarity is essential in creating communal bonds, but the very size of the nation renders this difficult, and micro-communities are therefore formed which ultimately serve to de-stabilize the larger power structure of the government. This is not only bad for the nation, but also for those who govern the nation, because it creates a distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’, and this perceived disparity dissolves the foundation of collective identity within the nation. As such, the elected representatives of modern democracies immediately find themselves juxtaposed with a large group of disgruntled citizens who have no true loyalty to the nation, and are instead controlled by purely by legislative force alone. In the worst case scenario, this leads to both ressentiment and revolution.

Nietzsche also espouses this sentiment in The Birth of Tragedy where he describes culture as the “most basic foundation of the life of a people”.6 The modern nation however has become increasingly complex and the more it grows, the weaker the ties to the people and the concept of Being in the nation becomes. Familiarity is essential in creating communal bonds, but the very size of the nation renders this difficult, and micro-communities are therefore formed which ultimately serve to de-stabilize the larger power structure of the government. This is not only bad for the nation, but also for those who govern the nation, because it creates a distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’, and this perceived disparity dissolves the foundation of collective identity within the nation. As such, the elected representatives of modern democracies immediately find themselves juxtaposed with a large group of disgruntled citizens who have no true loyalty to the nation, and are instead controlled by purely by legislative force alone. In the worst case scenario, this leads to both ressentiment and revolution. In regards to music and its effect on politics and culture, another figure connected to Nietzsche who cannot be ignored is the ever-present specter of Richard Wagner. Ultimately the friendship of the two was not based purely on passion for music, but also the use of mythology, something with Richard Wagner indisputably drew upon in his operas. Wagner wrote in Deutsche Kunst and Deutsche Politik on the social and political meaning of such aesthetic theories: “Modern life, Wagner wrote, [shall be] reorganized by the rebirth of art, and especially by a new theater whose life-giving function shall be equal to that of ancient Greek drama”.17 Although Nietzsche would eventually separate himself from Wagner due to the musician’s anti-Semitism, Nietzsche also explored the uses of myth during his period of friendship with Wagner. “The legend of Prometheus”, Nietzsche writes,

In regards to music and its effect on politics and culture, another figure connected to Nietzsche who cannot be ignored is the ever-present specter of Richard Wagner. Ultimately the friendship of the two was not based purely on passion for music, but also the use of mythology, something with Richard Wagner indisputably drew upon in his operas. Wagner wrote in Deutsche Kunst and Deutsche Politik on the social and political meaning of such aesthetic theories: “Modern life, Wagner wrote, [shall be] reorganized by the rebirth of art, and especially by a new theater whose life-giving function shall be equal to that of ancient Greek drama”.17 Although Nietzsche would eventually separate himself from Wagner due to the musician’s anti-Semitism, Nietzsche also explored the uses of myth during his period of friendship with Wagner. “The legend of Prometheus”, Nietzsche writes, This is Nietzshe’s Geisterkrieg – a war of ideas that is to fought at the academic and intellectual level to control the flow of ideas, culture, and the politics that emerge from it. This is similar to the modern idea of “metapolitics”. The Geisterkrieg however, “cuts right through the absurd arbitrariness that are peoples, class, race, profession, education, culture,” a war instead “between ascending and declining, between will-to-live and the desire for revenge on life”.29 In the context of the Geisterkrieg and Grosse Politik, the artists and the philosophers become the creators of all future governments and orders – for as Nietzsche tells us, “The artist and philosopher […] strike only a few and should strike all”.30 This means that they have not yet realized their ability to create cultural changes. Only the artists and philosophers are capable of launching Nietzsche’s Geisterkrieg, the war of ideas. However, due to the current dominance of capitalism and production based society over democracy (across both the Left and Right) the influence of artists and philosophers are severely impaired. And because of this, their rule continues unchallenged because Nietzsche’s Geisterkrieg, if successful, would end all petty nationalism and party specific squabbles. Partisan based politics would no longer exist, replaced instead by leaders who embody thymos the most as is stated here,

This is Nietzshe’s Geisterkrieg – a war of ideas that is to fought at the academic and intellectual level to control the flow of ideas, culture, and the politics that emerge from it. This is similar to the modern idea of “metapolitics”. The Geisterkrieg however, “cuts right through the absurd arbitrariness that are peoples, class, race, profession, education, culture,” a war instead “between ascending and declining, between will-to-live and the desire for revenge on life”.29 In the context of the Geisterkrieg and Grosse Politik, the artists and the philosophers become the creators of all future governments and orders – for as Nietzsche tells us, “The artist and philosopher […] strike only a few and should strike all”.30 This means that they have not yet realized their ability to create cultural changes. Only the artists and philosophers are capable of launching Nietzsche’s Geisterkrieg, the war of ideas. However, due to the current dominance of capitalism and production based society over democracy (across both the Left and Right) the influence of artists and philosophers are severely impaired. And because of this, their rule continues unchallenged because Nietzsche’s Geisterkrieg, if successful, would end all petty nationalism and party specific squabbles. Partisan based politics would no longer exist, replaced instead by leaders who embody thymos the most as is stated here,