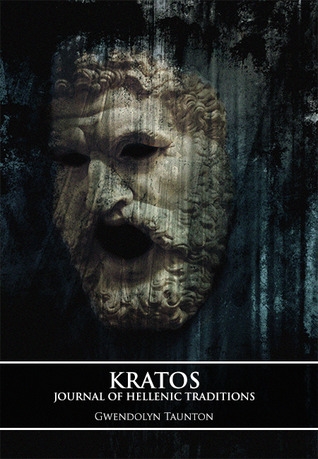

The Black Sun: Dionysus, Nietzsche, and Greek Myth

Gwendolyn Taunton

Ex: https://manticorepress.net

“Affirmation of life even it its strangest and sternest problems, the will to life rejoicing in its own inexhaustibility through the sacrifice of its highest types – that is what I call the Dionysian…Not so as to get rid of pity and terror, not so as to purify oneself of a dangerous emotion through its vehement discharge – it was thus Aristotle understood it – but, beyond pity and terror, to realize in oneself the eternal joy of becoming – that joy which also encompasses joy in destruction…And with that I again return to that place from which I set out –The Birth of Tragedy was my first revaluation of all values: with that I again plant myself in the soil out of which I draw all that I will and can – I, the last disciple of the philosopher Dionysus – I, the teacher of the eternal recurrence…(Nietzsche, “What I Owe to the Ancients”)

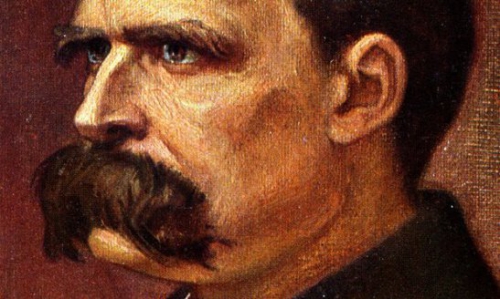

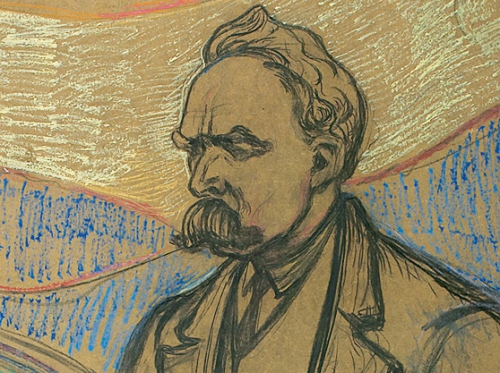

It is a well known fact that most of the early writings of the German philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche, revolve around a prognosis of duality concerning the two Hellenic deities, Apollo and Dionysus. This dichotomy, which first appears in The Birth of Tragedy, is subsequently modified by Nietzsche in his later works so that the characteristics of the God Apollo are reflected and absorbed by his polar opposite, Dionysus. Though this topic has been examined frequently by philosophers, it has not been examined sufficiently in terms of its relation to the Greek myths which pertain to the two Gods in question. Certainly, Nietzsche was no stranger to Classical myth, for prior to composing his philosophical works, Nietzsche was a professor of Classical Philology at the University of Basel. This interest in mythology is also illustrated in his exploration of the use of mythology as tool by which to shape culture. The Birth of Tragedy is based upon Greek myth and literature, and also contains much of the groundwork upon which he would develop his later premises. Setting the tone at the very beginning of The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche writes:[spacer height=”20px”]

We shall have gained much for the science of aesthetics, once we perceive not merely by logical inference, but with the immediate certainty of vision, that the continuous development of art is bound up with the Apollonian and Dionysian duality – just as procreation depends on the duality of the sexes, involving perpetual strife with only periodically intervening reconciliations. The terms Dionysian and Apollonian we borrow from the Greeks, who disclose to the discerning mind the profound mysteries of their view of art, not, to be sure, in concepts, but in the intensely clear figures of their gods. Through Apollo and Dionysus, the two art deities of the Greeks, we come to recognize that in the Greek world there existed a tremendous opposition…[1]

Initially then, Nietzsche’s theory concerning Apollo and Dionysus was primarily concerned with aesthetic theory, a theory which he would later expand to a position of predominance at the heart of his philosophy. Since Nietzsche chose the science of aesthetics as the starting point for his ideas, it is also the point at which we shall begin the comparison of his philosophy with the Hellenic Tradition.

The opposition between Apollo and Dionysus is one of the core themes within The Birth of Tragedy, but in Nietzsche’s later works, Apollo is mentioned only sporadically, if at all, and his figure appears to have been totally superseded by his rival Dionysus. In The Birth of Tragedy, Apollo and Dionysus are clearly defined by Nietzsche, and the spheres of their influence are carefully demarcated. In Nietzsche’s later writings, Apollo is conspicuous by the virtue of his absence – Dionysus remains and has ascended to a position of prominence in Nietzsche’s philosophy, but Apollo, who was an integral part of the dichotomy featured in The Birth of Tragedy, has disappeared, almost without a trace. There is in fact, a simple reason for the disappearance of Apollo – he is in fact still present, within the figure of Dionysus. What begins in The Birth of Tragedy as a dichotomy shifts to synthesis in Nietzsche’s later works, with the name Dionysus being used to refer to the unified aspect of both Apollo and Dionysus, in what Nietzsche believes to the ultimate manifestation of both deities. In early works the synthesis between Apollo & Dionysus is incomplete – they are still two opposing principles – “Thus in The Birth of Tragedy, Apollo, the god of light, beauty and harmony is in opposition to Dionysian drunkenness and chaos”.[2] The fraternal union of Apollo & Dionysus that forms the basis of Nietzsche’s view is, according to him, symbolized in art, and specifically in Greek tragedy.[3] Greek tragedy, by its fusion of dialogue and chorus; image and music, exhibits for Nietzsche the union of the Apollonian and Dionysian, a union in which Dionysian passion and dithyrambic madness merge with Apollonian measure and lucidity, and original chaos and pessimism are overcome in a tragic attitude that is affirmative and heroic.[4]

The moment of Dionysian “terror” arrives when […] a cognitive failure or wandering occurs, when the principle of individuation, which is Apollo’s “collapses” […] and gives way to another perception, to a contradiction of appearances and perhaps even to their defeasibility as such (their “exception”). It occurs “when [one] suddenly loses faith in […] the cognitive form of phenomena. Just as dreams […] satisfy profoundly our innermost being, our common [deepest] ground [der gemeinsame Untergrund], so too, symmetrically, do “terror” and “blissful” ecstasy…well up from the innermost depths [Grunde] of man once the strict controls of the Apollonian principle relax. Then “we steal a glimpse into the nature of the Dionysian”.[5]

The Apollonian and the Dionysian are two cognitive states in which art appears as the power of nature in man.[6] Art for Nietzsche is fundamentally not an expression of culture, but is what Heidegger calls “eine Gestaltung des Willens zur Macht” a manifestation of the will to power. And since the will to power is the essence of being itself, art becomes “die Gestaltung des Seienden in Ganzen,” a manifestation of being as a whole.[7] This concept of the artist as a creator, and of the aspect of the creative process as the manifestation of the will, is a key component of much of Nietzsche’s thought – it is the artist, the creator who diligently scribes the new value tables. Taking this into accord, we must also allow for the possibility that Thus Spake Zarathustra opens the doors for a new form of artist, who rather than working with paint or clay, instead provides the Uebermensch, the artist that etches their social vision on the canvas of humanity itself. It is in the character of the Uebermensch that we see the unification of the Dionysian (instinct) and Apollonian (intellect) as the manifestation of the will to power, to which Nietzsche also attributes the following tautological value “The Will to Truth is the Will to Power”.[8] This statement can be interpreted as meaning that by attributing the will to instinct, truth exists as a naturally occurring phenomena – it exists independently of the intellect, which permits many different interpretations of the truth in its primordial state. The truth lies primarily in the will, the subconscious, and the original raw instinctual state that Nietzsche identified with Dionysus. In The Gay Science Nietzsche says:

The Apollonian and the Dionysian are two cognitive states in which art appears as the power of nature in man.[6] Art for Nietzsche is fundamentally not an expression of culture, but is what Heidegger calls “eine Gestaltung des Willens zur Macht” a manifestation of the will to power. And since the will to power is the essence of being itself, art becomes “die Gestaltung des Seienden in Ganzen,” a manifestation of being as a whole.[7] This concept of the artist as a creator, and of the aspect of the creative process as the manifestation of the will, is a key component of much of Nietzsche’s thought – it is the artist, the creator who diligently scribes the new value tables. Taking this into accord, we must also allow for the possibility that Thus Spake Zarathustra opens the doors for a new form of artist, who rather than working with paint or clay, instead provides the Uebermensch, the artist that etches their social vision on the canvas of humanity itself. It is in the character of the Uebermensch that we see the unification of the Dionysian (instinct) and Apollonian (intellect) as the manifestation of the will to power, to which Nietzsche also attributes the following tautological value “The Will to Truth is the Will to Power”.[8] This statement can be interpreted as meaning that by attributing the will to instinct, truth exists as a naturally occurring phenomena – it exists independently of the intellect, which permits many different interpretations of the truth in its primordial state. The truth lies primarily in the will, the subconscious, and the original raw instinctual state that Nietzsche identified with Dionysus. In The Gay Science Nietzsche says:

For the longest time, thinking was considered as only conscious, only now do we discover the truth that the greatest part of our intellectual activity lies in the unconscious […] theories of Schopenhauer and his teaching of the primacy of the will over the intellect. The unconscious becomes a source of wisdom and knowledge that can reach into the fundamental aspects of human existence, while the intellect is held to be an abstracting and falsifying mechanism that is directed, not toward truth but toward “mastery and possession.” [9]

Thus the will to power originates not in the conscious, but in the subconscious. Returning to the proposed dichotomy betwixt Dionysus and Apollo, in his later works the two creative impulses become increasingly merged, eventually reaching a point in his philosophy wherein Dionysus refers not to the singular God, but rather a syncretism of Apollo and Dionysus in equal quantity. “The two art drives must unfold their powers in a strict proportion, according to the law of eternal justice.”[10] For Nietzsche, the highest goal of tragedy is achieved in the harmony between two radically distinct realms of art, between the principles that govern the Apollonian plastic arts and epic poetry and those that govern the Dionysian art of music.[11] To be complete and to derive ultimate mastery from the creative process, one must harness both the impulses represented by Apollo and Dionysus – the instinctual urge and potent creative power of Dionysus, coupled with the skill and intellectualism of Apollo’s craftsmanship – in sum both natural creative power from the will and the skills learnt within a social grouping. This definition will hold true for all creative ventures and is not restricted to the artistic process; ‘will’ and ‘skill’ need to act in harmony and concord.

In Nietzsche’s philosophy, Apollo and Dionysus are so closely entwined as to render them inseparable. Apollo, as the principle of appearance and of individuation, is that which grants appearance to the Dionysian form, without for Apollo, Dionysus remains bereft of physical appearance.

That [Dionysus] appears at all with such epic precision and clarity is the work of the dream interpreter, Apollo […] His appearances are at best instances of “typical ‘ideality,’” epiphanies of the “idea” or “idol”, mere masks and after images (Abbilde[er]). To “appear” Dionysus must take on a form.[12]

In his natural state, Dionysus has no form, it is only by reflux with Apollo, who represents the nature of form that Dionysus, as the nature of the formless, can appear to us at all. Likewise, Apollo without Dionysus becomes lost in a world of form – the complex levels of abstraction derived from the Dionysian impulse are absent. Neither god can function effectively without the workings of the other. Dionysus appears, after all, only thanks to the Apollonian principle. This is Nietzsche’s rendition of Apollo and Dionysus, his reworking of the Hellenic mythos, forged into a powerful philosophy that has influenced much of the modern era. Yet how close is this new interpretation to the original mythology of the ancient Greeks, and how much of this is Nietzsche’s own creation? It is well known that Nietzsche and his contemporary Wagner both saw the merit in reshaping old myths to create new socio-political values. To fully understand Nietzsche’s retelling of the Dionysus myth and separate the modern ideas from that of the ancients, we need to examine the Hellenic sources on Dionysus.

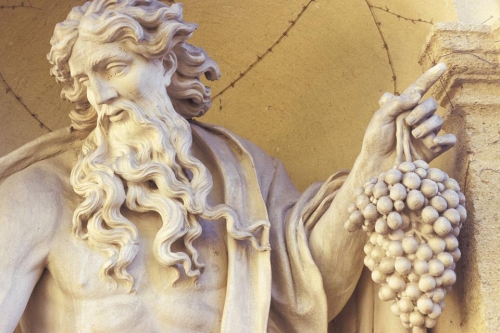

Myths of Dionysus are often used to depict a stranger or an outsider to the community as a repository for the mysterious and prohibited features of another culture. Unsavory characteristics that the Greeks tend to ascribe to foreigners are attributed to him, and various myths depict his initial rejection by the authority of the polis – yet Dionysus’ birth at Thebes, as well as the appearance of his name on Linear B tablets, indicates that this is no stranger, but in fact a native, and that the rejected foreign characteristics ascribed to him are in fact Greek characteristics.[13] Rather than being a representative of foreign culture what we are in fact observing in the character of Dionysus is the archetype of the outsider; someone who sits outside the boundaries of the cultural norm, or who represents the disruptive element in society which either by its nature effects a change or is removed by the culture which its very presence threatens to alter. Dionysus represents as Plutarch observed, “the whole wet element” in nature – blood, semen, sap, wine, and all the life giving juice. He is in fact a synthesis of both chaos and form, of orgiastic impulses and visionary states – at one with the life of nature and its eternal cycle of birth and death, of destruction and creation.[14] This disruptive element, by being associated with the blood, semen, sap, and wine is an obvious metaphor for the vital force itself, the wet element, being representative of “life in the raw”. This notion of “life” is intricately interwoven into the figure of Dionysus in the esoteric understanding of his cult, and indeed throughout the philosophy of the Greeks themselves, who had two different words for life, both possessing the same root as Vita (Latin: Life) but present in very different phonetic forms: bios and zoë.[15]

Myths of Dionysus are often used to depict a stranger or an outsider to the community as a repository for the mysterious and prohibited features of another culture. Unsavory characteristics that the Greeks tend to ascribe to foreigners are attributed to him, and various myths depict his initial rejection by the authority of the polis – yet Dionysus’ birth at Thebes, as well as the appearance of his name on Linear B tablets, indicates that this is no stranger, but in fact a native, and that the rejected foreign characteristics ascribed to him are in fact Greek characteristics.[13] Rather than being a representative of foreign culture what we are in fact observing in the character of Dionysus is the archetype of the outsider; someone who sits outside the boundaries of the cultural norm, or who represents the disruptive element in society which either by its nature effects a change or is removed by the culture which its very presence threatens to alter. Dionysus represents as Plutarch observed, “the whole wet element” in nature – blood, semen, sap, wine, and all the life giving juice. He is in fact a synthesis of both chaos and form, of orgiastic impulses and visionary states – at one with the life of nature and its eternal cycle of birth and death, of destruction and creation.[14] This disruptive element, by being associated with the blood, semen, sap, and wine is an obvious metaphor for the vital force itself, the wet element, being representative of “life in the raw”. This notion of “life” is intricately interwoven into the figure of Dionysus in the esoteric understanding of his cult, and indeed throughout the philosophy of the Greeks themselves, who had two different words for life, both possessing the same root as Vita (Latin: Life) but present in very different phonetic forms: bios and zoë.[15]

Plotinos called zoë the “time of the soul”, during which the soul, in its course of rebirths, moves on from one bios to another […] the Greeks clung to a not-characterized “life” that underlies every bios and stands in a very different relationship to death than does a “life” that includes death among its characteristics […] This experience differs from the sum of experiences that constitute the bios, the content of each individual man’s written or unwritten biography. The experience of life without characterization – of precisely that life which “resounded” for the Greeks in the word zoë – is, on the other hand, indescribable.[16]

Zoë is Life in its immortal and transcendent aspect, and is thus representative of the pure primordial state. Zoëis the presupposition of the death drive; death exists only in relation to zoë. It is a product of life in accordance with a dialectic that is a process not of thought, but of life itself, of the zoë in each individual bios.[17]

The other primary association of Dionysus is with the chthonic elements, and we frequently find him taking the form of snakes. According to the myth of his dismemberment by the Titans, a myth which is strongly associated with Delphi, he was born of Persephone, after Zeus, taking snake form, had impregnated her. [18] In Euripides Bacchae, Dionysus, being the son of Semele, is a god of dark and frightening subterranean powers; yet being also the son of Zeus, he mediates between the chthonic and civilized worlds, once again playing the role of a liminal outsider that passes in transit from one domain to another.[19] Through his association with natural forces, a description of his temple has been left to us by a physician from Thasos: “A temple in the open air, an open air naos with an altar and a cradle of vine branches; a fine lair, always green; and for the initiates a room in which to sing the evoe.”[20] This stands in direct contrast to Apollo, who was represented by architectural and artificial beauty. Likewise his music was radically different to that of Apollo’s; “A stranger, he should be admitted into the city, for his music is varied, not distant and monotone like the tunes of Apollo’s golden lyre”. (Euripides Bacchae 126-134, 155-156)[21]

Both Gods were concerned with the imagery of life, art, and as we shall see soon, the sun. Moreover, though their forces were essentially opposite, they two Gods were essentially representative of two polarities for the same force, meeting occasionally in perfect balance to reveal an unfolding Hegelian dialectic that was the creative process of life itself and the esoteric nature of the solar path, for just as Dionysus was the chthonic deity (and here we intentionally use the word Chthon instead of the word Gē – Chthon being literally underworld and Gē being the earth or ground) and Apollo was a Solar deity; but not the physical aspect of the sun as a heavenly body, this was ascribed by to the god Helios instead. Rather Apollo represented the human aspect of the solar path (and in this he is equivalent to the Vedic deity Savitar), and its application to the mortal realm; rather than being the light of the sky, Apollo is the light of the mind: intellect and creation. He is as bright as Dionysus is dark – in Dionysus the instinct, the natural force of zoë is prevalent, associated with the chthonic world below ground because he is immortal, his power normally unseen. He rules during Apollo’s absence in Hyperborea because the sun has passed to another land, the reign of the bright sun has passed and the time of the black sun commences – the black sun being the hidden aspect of the solar path, represented by the departure of Apollo in this myth.

Apollo is frequently mentioned in connection to Dionysus in Greek myth. Inscriptions dating from the third century B.C., mention that Dionysos Kadmeios reigned alongside Apollo over the assembly of Theben gods.[22] Likewise on Rhodes a holiday called Sminthia was celebrated there in memory of a time mice attacked the vines there and were destroyed by Apollo and Dionysus, who shared the epithet Sminthios on the island.[23] They are even cited together in the Odyssey (XI 312-25), and also in the story of the death of Koronis, who was shot by Artemis, and this at Apollo’s instigation because she had betrayed the god with a mortal lover.[24] Also, the twin peaks on Parnassos traditionally known as the “peaks of Apollo and Dionysus.”[25] Their association and worship however, was even more closely entwined at Delphi, for as Leicester Holland has perceived:

(1) Dionysus spoke oracles at Delphi before Apollo did; (2) his bones were placed in a basin beside the tripod; (3) the omphalos was his tomb. It is well known, moreover, that Dionysus was second only to Apollo in Delphian and Parnassian worship; Plutarch, in fact, assigns to Dionysus an equal share with Apollo in Delphi[26]

A Pindaric Scholiast says that Python ruled the prophetic tripod on which Dionysus was the first to speak oracles; that then Apollo killed the snake and took over.[27] The association of Apollo and Dionysus in Delphi, moreover, was not limited to their connection to the Delphic Oracle. We also find this relationship echoed in the commemoration of the Great flood which was celebrated each year at a Delphian festival called Aiglē, celebrated two or three days before the full moon of January or February, at the same time as the Athenian Anthesteria festival, the last day of which was devoted to commemorating the victims of the Great Flood; this was the same time of the year when Apollo was believed at Delphi to return from his sojourn among the Hyperboreans. Moreover, Dionysus is said to have perished and returned to life in the flood.[28] Apollo’s Hyperborean absence is his yearly death – Apollonios says that Apollo shed tears when he went to the Hyperborean land; thence flows the Eridanos, on whose banks the Heliades wail without cease; and extremely low spirits came over the Argonauts as they sailed that river of amber tears.[29]

This is the time of Dionysus’ reign at Delphi in which he was the center of Delphic worship for the three winter months, when Apollo was absent. Plutarch, himself a priest of the Pythian Apollo, Amphictyonic official and a frequent visitor to Delphi, says that for nine months the paean was sung in Apollo’s honour at sacrifices, but at the beginning of winter the paeans suddenly ceased, then for three months men sang dithyrambs and addressed themselves to Dionysus rather than to Apollo.[30] Chthonian Dionysus manifested himself especially at the winter festival when the souls of the dead rose to walk briefly in the upper world again, in the festival that the Athenians called Anthesteria, whose Delphian counterpart was the Theophania. The Theophania marked the end of Dionysus’ reign and Apollo’s return; Dionysus and the ghosts descended once more to Hades realm.[31] In this immortal aspect Dionysus is very far removed from being a god of the dead and winter; representing instead immortal life, the zoë, which was employed in Dionysian cult to release psychosomatic energies summoned from the depths that were discharged in a physical cult of life.[32]

Dionysus is the depiction of transcendent primordial life, life that persists even during the absence of Apollo (the Sun) – for as much as Apollo is the Golden Sun, Dionysus is the Black or Winter Sun, reigning in the world below ground whilst Apollo’s presence departs for another hemisphere, dead to the people of Delphi, the Winter Sun reigns in Apollo’s absence. Far from being antagonistic opposites, Apollo and Dionysus were so closely related in Greek myth that according to Deinarchos, Dionysus was killed and buried at Delphi beside the golden Apollo.[33] Likewise, in the Lykourgos tetralogy of Aischylos, the cry “Ivy-Apollo, Bakchios, the soothsayer,” is heard when the Thracian bacchantes, the Bassarai, attacks Orpheus, the worshipper of Apollo and the sun. The cry suggests a higher knowledge of the connection between Apollo and Dionysus, the dark god, whom Orpheus denies in favour of the luminous god. In the Lykymnios of Euripides the same connection is attested by the cry, “Lord, laurel-loving Bakchios, Paean Apollo, player of the Lyre.”[34] Similarly, we find anotherpaean by Philodamos addressed to Dionysus from Delphi: “Come hither, Lord Dithyrambos, Backchos…..Bromios now in the spring’s holy period.”[35] The pediments of the temple of Apollo also portray on one side Apollo with Leto, Artemis, and the Muses, and on the other side Dionysus and the thyiads, and a vase painting of c.400 B.C. shows Apollo and Dionysus in Delphi holding their hands to one another.[36]

An analysis of Nietzsche’s philosophy concerning the role of Apollo and Dionysus in Hellenic myth thus reveals more than even a direct parallel. Not only did Nietzsche comprehend the nature of the opposition between Apollo and Dionysus, he understood this aspect of their cult on the esoteric level, that their forces, rather than being antagonistic are instead complementary, with both Gods performing two different aesthetic techniques in the service of the same social function, which reaches its pinnacle of development when both creative processes are elevated in tandem within an individual. Nietzsche understood the symbolism of myths and literature concerning the two gods, and he actually elaborated upon it, adding the works of Schopenhauer to create a complex philosophy concerning not only the interplay of aesthetics in the role of the creative process, but also the nature of the will and the psychological process used to create a certain type, which is exemplified in both his ideals of the Ubermensch and the Free Spirit. Both of these higher types derive their impetus from the synchronicity of the Dionysian and Apollonian drives, hence why in Nietzsche’s later works following The Birth of Tragedy only the Dionysian impulse is referred to, this term not being used to signify just Dionysus, but rather the balanced integration of the two forces. This ideal of eternal life (zoë) is also located in Nietzsche’s theory of Eternal Reoccurrence – it denies the timeless eternity of a supernatural God, but affirms the eternity of the ever-creating and destroying powers in nature and man, for like the solar symbolism of Apollo and Dionysus, it is a notion of cyclical time. To Nietzsche, the figure of Dionysus is the supreme affirmation of life, the instinct and the will to power, with the will to power being an expression of the will to life and to truth at its highest exaltation – “It is a Dionysian Yea-Saying to the world as it is, without deduction, exception and selection…it is the highest attitude that a philosopher can reach; to stand Dionysiacally toward existence: my formula for this is amor fati”’[37] Dionysus is thus to both Nietzsche and the Greeks, the highest expression of Life in its primordial and transcendent meaning, the hidden power of the Black Sun and the subconscious impulse of the will.

To order at: https://manticorepress.net

Endnotes:

[1]James I. Porter, The Invention of Dionysus: An Essay on the Birth of Tragedy, (California: Stanford University Press, 2002), 40

[2]Rose Pfeffer, Nietzsche: Disciple of Dionysus, (New Jersey: Associated University Presses, Inc. 1977), 31

[3] Ibid.,31

[4] Ibid., 51

[5] James I. Porter, The Invention of Dionysus: An Essay on the Birth of Tragedy, 50-51

[6] Ibid., 221

[7] Ibid., 205-206

[8] Rose Pfeffer, Nietzsche: Disciple of Dionysus, 114

[9] Ibid, 113

[10] James I. Porter, The Invention of Dionysus: An Essay on the Birth of Tragedy, 82

[11] Rose Pfeffer, Nietzsche: Disciple of Dionysus, 32

[12] James I. Porter, The Invention of Dionysus: An Essay on the Birth of Tragedy, 99

[13]Dora C. Pozzi, and John M. Wickerman, Myth & the Polis, (New York: Cornell University 1991), 36

[14]Rose Pfeffer, Nietzsche: Disciple of Dionysus, 126

[15] Carl Kerényi, Dionysos Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life, (New Jersey: Princeton university press, 1996), xxxxi

[16] Ibid., xxxxv

[17] Ibid., 204-205

[18] Joseph Fontenrose, Python: A Study of Delphic Myth and its Origins (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980), 378

[19]Dora C. Pozzi, and John M. Wickerman, Myth & the Polis, 147

[20]Marcel Detienne, trans. Arthur Goldhammer Dionysos At Large, (London: Harvard Univeristy Press 1989), 46

[21]Dora C. Pozzi, and John M. Wickerman, Myth & the Polis, 144

[22] Marcel Detienne, trans. Arthur Goldhammer Dionysos At Large, 18

[23] Daniel E. Gershenson, Apollo the Wolf-God in Journal of Indo-European Studies, Mongraph number 8 (Virginia: Institute for the Study of Man 1991), 32

[24]Carl Kerényi, Dionysos Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life, (New Jersey: Princeton university press, 1996), 103

[25] Dora C. Pozzi, and John M. Wickerman, Myth & the Polis, 139

[26] Joseph Fontenrose, Python: A Study of Delphic Myth and its Origins (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980), 375

[27] Ibid., 376

[28]Daniel E. Gershenson, Apollo the Wolf-God in Journal of Indo-European Studies, Monograph number 8, 61

[29] Joseph Fontenrose, Python: A Study of Delphic Myth and its Origins (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980), 387

[30] Ibid., 379

[31] Ibid., 380-381

[32] Ibid., 219

[33] Ibid., 388

[34] Carl Kerényi, Dionysos Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life, (New Jersey: Princeton university press, 1996), 233

[35] Ibid.,217

[36] Walter F. Otto, Dionysus: Myth and Cult, (Dallas: Spring Publications, 1989) 203

[37] Rose Pfeffer, Nietzsche: Disciple of Dionysus, 261

The Apollonian and the Dionysian are two cognitive states in which art appears as the power of nature in man.[6] Art for Nietzsche is fundamentally not an expression of culture, but is what Heidegger calls “eine Gestaltung des Willens zur Macht” a manifestation of the will to power. And since the will to power is the essence of being itself, art becomes “die Gestaltung des Seienden in Ganzen,” a manifestation of being as a whole.[7] This concept of the artist as a creator, and of the aspect of the creative process as the manifestation of the will, is a key component of much of Nietzsche’s thought – it is the artist, the creator who diligently scribes the new value tables. Taking this into accord, we must also allow for the possibility that Thus Spake Zarathustra opens the doors for a new form of artist, who rather than working with paint or clay, instead provides the Uebermensch, the artist that etches their social vision on the canvas of humanity itself. It is in the character of the Uebermensch that we see the unification of the Dionysian (instinct) and Apollonian (intellect) as the manifestation of the will to power, to which Nietzsche also attributes the following tautological value “The Will to Truth is the Will to Power”.[8] This statement can be interpreted as meaning that by attributing the will to instinct, truth exists as a naturally occurring phenomena – it exists independently of the intellect, which permits many different interpretations of the truth in its primordial state. The truth lies primarily in the will, the subconscious, and the original raw instinctual state that Nietzsche identified with Dionysus. In The Gay Science Nietzsche says:

The Apollonian and the Dionysian are two cognitive states in which art appears as the power of nature in man.[6] Art for Nietzsche is fundamentally not an expression of culture, but is what Heidegger calls “eine Gestaltung des Willens zur Macht” a manifestation of the will to power. And since the will to power is the essence of being itself, art becomes “die Gestaltung des Seienden in Ganzen,” a manifestation of being as a whole.[7] This concept of the artist as a creator, and of the aspect of the creative process as the manifestation of the will, is a key component of much of Nietzsche’s thought – it is the artist, the creator who diligently scribes the new value tables. Taking this into accord, we must also allow for the possibility that Thus Spake Zarathustra opens the doors for a new form of artist, who rather than working with paint or clay, instead provides the Uebermensch, the artist that etches their social vision on the canvas of humanity itself. It is in the character of the Uebermensch that we see the unification of the Dionysian (instinct) and Apollonian (intellect) as the manifestation of the will to power, to which Nietzsche also attributes the following tautological value “The Will to Truth is the Will to Power”.[8] This statement can be interpreted as meaning that by attributing the will to instinct, truth exists as a naturally occurring phenomena – it exists independently of the intellect, which permits many different interpretations of the truth in its primordial state. The truth lies primarily in the will, the subconscious, and the original raw instinctual state that Nietzsche identified with Dionysus. In The Gay Science Nietzsche says:

Myths of Dionysus are often used to depict a stranger or an outsider to the community as a repository for the mysterious and prohibited features of another culture. Unsavory characteristics that the Greeks tend to ascribe to foreigners are attributed to him, and various myths depict his initial rejection by the authority of the polis – yet Dionysus’ birth at Thebes, as well as the appearance of his name on Linear B tablets, indicates that this is no stranger, but in fact a native, and that the rejected foreign characteristics ascribed to him are in fact Greek characteristics.[13] Rather than being a representative of foreign culture what we are in fact observing in the character of Dionysus is the archetype of the outsider; someone who sits outside the boundaries of the cultural norm, or who represents the disruptive element in society which either by its nature effects a change or is removed by the culture which its very presence threatens to alter. Dionysus represents as Plutarch observed, “the whole wet element” in nature – blood, semen, sap, wine, and all the life giving juice. He is in fact a synthesis of both chaos and form, of orgiastic impulses and visionary states – at one with the life of nature and its eternal cycle of birth and death, of destruction and creation.[14] This disruptive element, by being associated with the blood, semen, sap, and wine is an obvious metaphor for the vital force itself, the wet element, being representative of “life in the raw”. This notion of “life” is intricately interwoven into the figure of Dionysus in the esoteric understanding of his cult, and indeed throughout the philosophy of the Greeks themselves, who had two different words for life, both possessing the same root as Vita (Latin: Life) but present in very different phonetic forms: bios and zoë.[15]

Myths of Dionysus are often used to depict a stranger or an outsider to the community as a repository for the mysterious and prohibited features of another culture. Unsavory characteristics that the Greeks tend to ascribe to foreigners are attributed to him, and various myths depict his initial rejection by the authority of the polis – yet Dionysus’ birth at Thebes, as well as the appearance of his name on Linear B tablets, indicates that this is no stranger, but in fact a native, and that the rejected foreign characteristics ascribed to him are in fact Greek characteristics.[13] Rather than being a representative of foreign culture what we are in fact observing in the character of Dionysus is the archetype of the outsider; someone who sits outside the boundaries of the cultural norm, or who represents the disruptive element in society which either by its nature effects a change or is removed by the culture which its very presence threatens to alter. Dionysus represents as Plutarch observed, “the whole wet element” in nature – blood, semen, sap, wine, and all the life giving juice. He is in fact a synthesis of both chaos and form, of orgiastic impulses and visionary states – at one with the life of nature and its eternal cycle of birth and death, of destruction and creation.[14] This disruptive element, by being associated with the blood, semen, sap, and wine is an obvious metaphor for the vital force itself, the wet element, being representative of “life in the raw”. This notion of “life” is intricately interwoven into the figure of Dionysus in the esoteric understanding of his cult, and indeed throughout the philosophy of the Greeks themselves, who had two different words for life, both possessing the same root as Vita (Latin: Life) but present in very different phonetic forms: bios and zoë.[15]

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Nietzsche also espouses this sentiment in The Birth of Tragedy where he describes culture as the “most basic foundation of the life of a people”.6 The modern nation however has become increasingly complex and the more it grows, the weaker the ties to the people and the concept of Being in the nation becomes. Familiarity is essential in creating communal bonds, but the very size of the nation renders this difficult, and micro-communities are therefore formed which ultimately serve to de-stabilize the larger power structure of the government. This is not only bad for the nation, but also for those who govern the nation, because it creates a distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’, and this perceived disparity dissolves the foundation of collective identity within the nation. As such, the elected representatives of modern democracies immediately find themselves juxtaposed with a large group of disgruntled citizens who have no true loyalty to the nation, and are instead controlled by purely by legislative force alone. In the worst case scenario, this leads to both ressentiment and revolution.

Nietzsche also espouses this sentiment in The Birth of Tragedy where he describes culture as the “most basic foundation of the life of a people”.6 The modern nation however has become increasingly complex and the more it grows, the weaker the ties to the people and the concept of Being in the nation becomes. Familiarity is essential in creating communal bonds, but the very size of the nation renders this difficult, and micro-communities are therefore formed which ultimately serve to de-stabilize the larger power structure of the government. This is not only bad for the nation, but also for those who govern the nation, because it creates a distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’, and this perceived disparity dissolves the foundation of collective identity within the nation. As such, the elected representatives of modern democracies immediately find themselves juxtaposed with a large group of disgruntled citizens who have no true loyalty to the nation, and are instead controlled by purely by legislative force alone. In the worst case scenario, this leads to both ressentiment and revolution. In regards to music and its effect on politics and culture, another figure connected to Nietzsche who cannot be ignored is the ever-present specter of Richard Wagner. Ultimately the friendship of the two was not based purely on passion for music, but also the use of mythology, something with Richard Wagner indisputably drew upon in his operas. Wagner wrote in Deutsche Kunst and Deutsche Politik on the social and political meaning of such aesthetic theories: “Modern life, Wagner wrote, [shall be] reorganized by the rebirth of art, and especially by a new theater whose life-giving function shall be equal to that of ancient Greek drama”.17 Although Nietzsche would eventually separate himself from Wagner due to the musician’s anti-Semitism, Nietzsche also explored the uses of myth during his period of friendship with Wagner. “The legend of Prometheus”, Nietzsche writes,

In regards to music and its effect on politics and culture, another figure connected to Nietzsche who cannot be ignored is the ever-present specter of Richard Wagner. Ultimately the friendship of the two was not based purely on passion for music, but also the use of mythology, something with Richard Wagner indisputably drew upon in his operas. Wagner wrote in Deutsche Kunst and Deutsche Politik on the social and political meaning of such aesthetic theories: “Modern life, Wagner wrote, [shall be] reorganized by the rebirth of art, and especially by a new theater whose life-giving function shall be equal to that of ancient Greek drama”.17 Although Nietzsche would eventually separate himself from Wagner due to the musician’s anti-Semitism, Nietzsche also explored the uses of myth during his period of friendship with Wagner. “The legend of Prometheus”, Nietzsche writes, This is Nietzshe’s Geisterkrieg – a war of ideas that is to fought at the academic and intellectual level to control the flow of ideas, culture, and the politics that emerge from it. This is similar to the modern idea of “metapolitics”. The Geisterkrieg however, “cuts right through the absurd arbitrariness that are peoples, class, race, profession, education, culture,” a war instead “between ascending and declining, between will-to-live and the desire for revenge on life”.29 In the context of the Geisterkrieg and Grosse Politik, the artists and the philosophers become the creators of all future governments and orders – for as Nietzsche tells us, “The artist and philosopher […] strike only a few and should strike all”.30 This means that they have not yet realized their ability to create cultural changes. Only the artists and philosophers are capable of launching Nietzsche’s Geisterkrieg, the war of ideas. However, due to the current dominance of capitalism and production based society over democracy (across both the Left and Right) the influence of artists and philosophers are severely impaired. And because of this, their rule continues unchallenged because Nietzsche’s Geisterkrieg, if successful, would end all petty nationalism and party specific squabbles. Partisan based politics would no longer exist, replaced instead by leaders who embody thymos the most as is stated here,

This is Nietzshe’s Geisterkrieg – a war of ideas that is to fought at the academic and intellectual level to control the flow of ideas, culture, and the politics that emerge from it. This is similar to the modern idea of “metapolitics”. The Geisterkrieg however, “cuts right through the absurd arbitrariness that are peoples, class, race, profession, education, culture,” a war instead “between ascending and declining, between will-to-live and the desire for revenge on life”.29 In the context of the Geisterkrieg and Grosse Politik, the artists and the philosophers become the creators of all future governments and orders – for as Nietzsche tells us, “The artist and philosopher […] strike only a few and should strike all”.30 This means that they have not yet realized their ability to create cultural changes. Only the artists and philosophers are capable of launching Nietzsche’s Geisterkrieg, the war of ideas. However, due to the current dominance of capitalism and production based society over democracy (across both the Left and Right) the influence of artists and philosophers are severely impaired. And because of this, their rule continues unchallenged because Nietzsche’s Geisterkrieg, if successful, would end all petty nationalism and party specific squabbles. Partisan based politics would no longer exist, replaced instead by leaders who embody thymos the most as is stated here,