Language. We take it for granted. We use it every day after all. It’s an unavoidable tool, necessary one and beautiful. One without which our lives would be diminished. But what happens when the native language of a people is replaced by another? What happens when these same people use this other language more than their own? This is unfortunately what has happened to Gaeilge, or Irish as most people know it. A beautiful tongue, on the brink of extinction.

How sad would it be to let one of our European languages disappear? In the struggle to remind our people at large of their heritage as well as the duty to their children and ancestors to carry on, we cannot forget the crucial aspect of culture, to which language is central. Gaeilge, Irish, is important. To 4 million Irelanders in Ireland. To their diaspora which numbers up to 70 million. To us, Europeans, as another part of the enormously rich tapestry that is our collective culture and history.

Let us not let it happen, eh?

What is the most distinguishing feature of a people, other than genetics? Is it their culture? Their history? Their place in the world, geographically speaking?

It’s their language. Teanga in Gaeilge

The foremost of differences, aside one of the easiest to observe.

Language is the way humans interact with one another. We convey meaning and ideas and thoughts through language. It is one of our most important tools. One of the first we learn as a child.

So what would happen to a people who are undergoing a… change to put it lightly, if their language was to disappear? Surely they would lose that most distinguishing of features? They may not even be able to call themselves a people, or a nation, any longer.

A History of Strife & Survival

It is no secret that the history of Humankind is also a history of warfare, the Irish are no exception to this rule. In their case, the battles ware against the Vikings, the Normans, and the English, or British as they would later call themselves… literal centuries of wars, struggles, revolutions…

Around 795 AD the Vikings came to Ireland from Scandinavia with the aim to steal and pillage Irish treasure and women.

By the end of the 10th century, Viking power was diminishing. The Viking era in Ireland is believed to have ended by 1014 when a large Viking Army was defeated in Clontarf by Brian Bórú, who is considered as Ireland’s greatest King.

In the 12th century, the Normans arrived in Ireland which began Ireland’s 800-year struggle with dear old England. In the 1600s the Ulster Plantation occurred in which Irish land was taken from Irish landowners and given to English families. This plantation of Ulster divided the country and this division still remains to this day. Then came Cromwell who arrived in Dublin in August 1649 and was intent on eradicating, as he saw it, the Irish problem once and for all. He despised Irish Catholics and together with his army he slaughtered and murdered, burnt houses and unplanted crops, leaving a trail of death and destruction across the Emerald Isle. He stole Irish land and granted it to moneylenders and English soldiers. He pushed most of the Irish and mainly Catholics, to the far side of the island where the land was poor and infertile. About a third of Catholics died through fighting, famine and disease.

The next 150 years saw more bloodshed and carnage on Irish soil between the Irish and English.

One of the biggest events in Ireland’s history over the last 200 years was ‘The Great Famine’. More than one million Irish died and more than one million emigrated due to the failure of their main crop, the potato, during the famine which lasted from 1845 to 1852. There are tales of roads strewn with dead Irish men, women and children with green around their mouths in a desperate attempt to quench their hunger by eating grass…

The late 1800s saw another push for Irish independence from England with the rise of Charles Stuart Parnell, one of Ireland’s greatest politicians. The Land League was formed with Charles Stuart Parnell as President. He tried to promote a more political way of dealing with the English. He promoted ‘shunning’, which meant that the Irish should refuse to deal with any landlord who unfairly evicted tenants or any Irish who took up the rent of new available land. This was known as the ‘Land War’. While Parnell never achieved Home Rule (Ireland run by its own independent Irish Parliament) it did lay the ground work for Ireland’s greatest uprising.

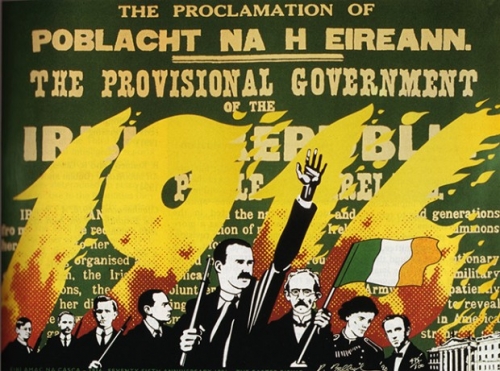

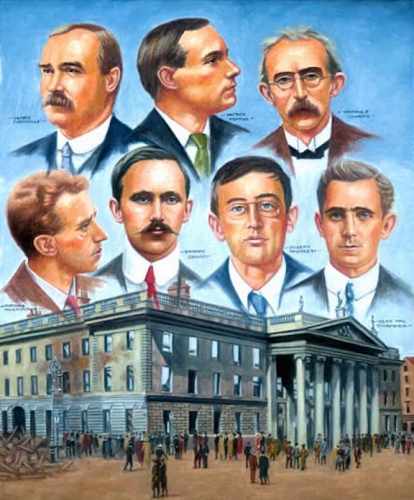

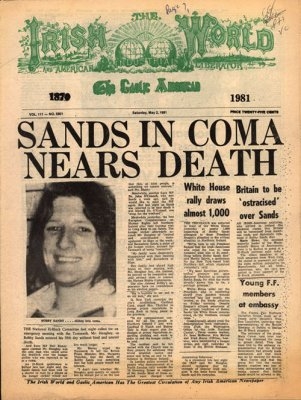

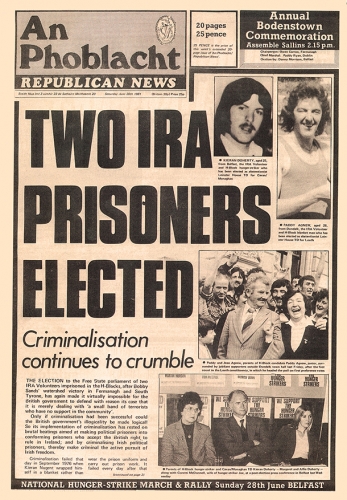

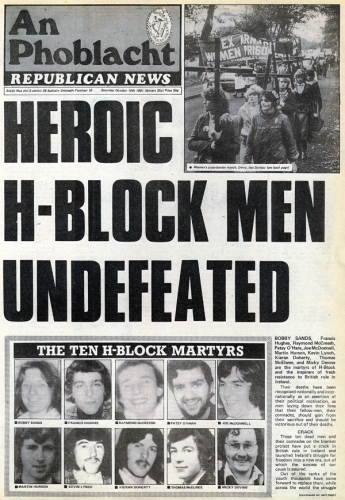

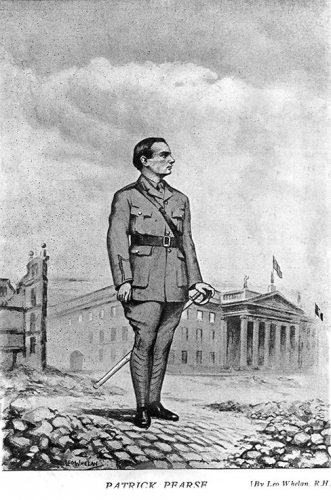

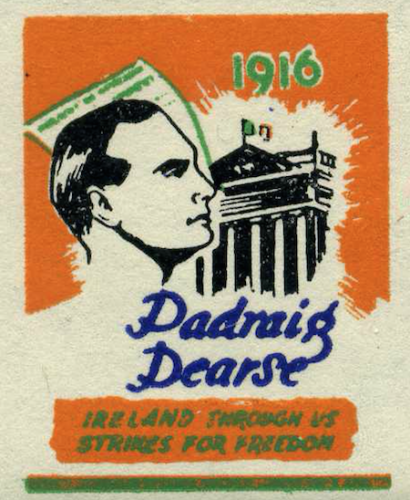

In 1916, Easter weekend, the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army launched an uprising. Britain was in the middle of World War 1. Padraig Pearse, who was one of the leaders of the rising, read the ‘Proclamation of the Irish Republic’ on the steps of the General Post Office (G.P.O) on O’Connell Street in Dublin before the start of the Rising. This uprising was in a sense a failure but lay the groundwork for greater things. The British rounded up its leaders and executed them. These executed later became martyrs.

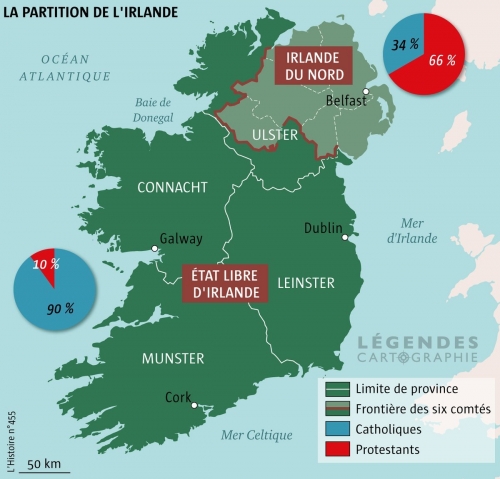

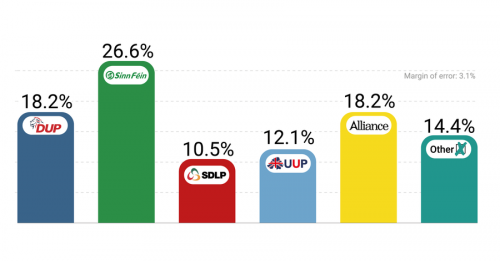

A new style of guerrilla warfare began, some time later. Bloodshed on Irish streets peaked with the execution of British Intelligence Agents in 1920 and the murder of many Irish, and innocent Irish at that, by the British ‘Black and Tans’. But by 1922, Ireland achieved independence from Britain, except for six counties in the Northern Ireland, which still remains part of Britain today. In 1922, post-boxes were painted green from the traditional British red, road signs were changed to contain both Irish and English language and the Tri-Colour flew high and proud around Ireland. Violence still continued though, with the ‘The Troubles’ in Northern Ireland peaking in the 1970s. Today, Ireland is peaceful with power-sharing in Northern Ireland between the main Catholic and Protestant Parties.

So much struggle and so much bloodshed, to now lose that for which they fought, because of… globalisation? Interconnectedness? The Nihilist plaque that assails the Continent at large?

All of Europe has endured much. It’s what’s made us so strong today. It’s for that reason the current situation is so infuriating. To have survived so much just to give it up for…comfort?

That’s a nay from me.

Language decay following Independence

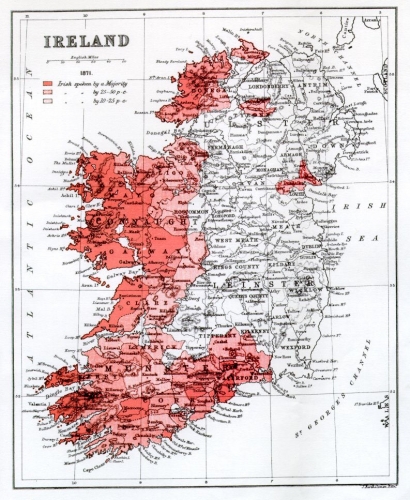

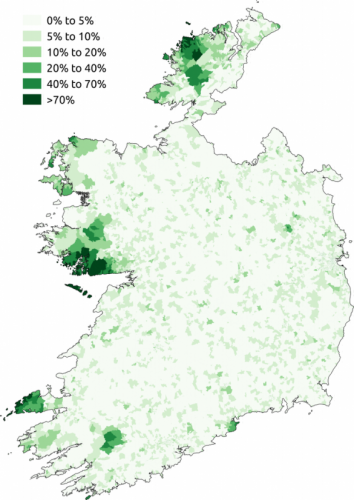

For much of Irish history, the English ruled Ireland, but Gaeilge, the language, only really began to decline after 1600, when the last of the Gaelic chieftains were defeated. While the Irish language was never banned or persecuted, it was discouraged. English was the official language of rule and business, there was no one to support the Irish language and culture. So, English slowly spread, especially in the East and in Dublin, the capital, while Irish remained strong in the West. By 1800, the Emerald Isle was roughly balanced between the two languages.

There were two major events that decimated Irish. The first was the Great Famine (1845-50) which hit the Irish speaking West hardest of all, out of a population of 8 million, about a million people died and another million emigrated. From then on emigration became a common part of Irish society as large numbers of Irish left the Isle every year, primarily to English speaking countries like America and Britain. So it was that most Irish people needed to speak English in the event that they would leave home.

English was the language of the future and of economic opportunity; Irish was the past and the language of a poverty-stricken island that couldn’t support them…

The second major event was the advent of education. Beginning in the 1830’s national schools were created across Ireland to educate people through English and Irish was strictly forbidden. While nothing could be done to prevent Irish from being spoken in the home, it was strongly discouraged and shamed. Irish was depicted as an ignorant peasant’s language, whereas English was the language of sophistication and wealth. Poor potato farmers spoke Irish, while rich and successful businessmen spoke English. Other organisations too promoted English, such as the Catholic Church and even Nationalist politicians like Daniel O’Connell. English became the language of the cities while Irish retreated to the most remote and underdeveloped parts of the country.

Languages are strongly subject to economies of scale. This is why immigrant families, if not very careful, lose the knowledge of their tongue, within two generations.

In the Irish example parents taught their children English because that was the language that most people spoke, which caused more people to learn it and so every generation English grew stronger and stronger. Likewise, Irish weakened as fewer people spoke it because few people spoke it which caused fewer still to speak it. It became more and more confined to elderly speakers which discouraged young people and continued the vicious circle. As fewer people spoke it, less people used it for art and literature, which gave people less of a reason to learn it. In short, Irish was/is trapped in a vicious downward spiral.

But there is hope, of course, Irish persists.

Gaeilge Revived

If we want to revive a language we’re gonna need some people to speak it, no? There have been good sings in recent years!

With some 70 million emigrants from Ireland spread throughout different countries, the Irish born, the Irish descendants and those who became enamoured with Irish culture have worked together in an effort to save the Irish language. Because of the hard work and study from many people all over the globe, in 2008 the Irish government took a nationwide survey to ask its citizens how they wanted to re-establish the nation’s first and official language. The Irish language is now in the process of working its way off the Endangered Languages list.

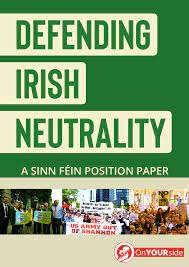

One of the major supporters dedicated to saving Irish is Foras na Gaeilge. Since 1999, the Foras na Gaeilge took on the responsibility of promoting Irish throughout Ireland. This group developed the Good Friday Agreement, which makes the promotion of the Irish language a joint effort between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, a major achievement. They were also instrumental in ensuring that Irish was added to the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages, making it a recognised language at the inception of the European Union.

There are positive developments every year regarding the language, more is required, more pushes and more effort, but the situation is improving and that is a good thing.

The Emerald Isle and above all, its people – na hÉireannaigh (the Irish), will live on!

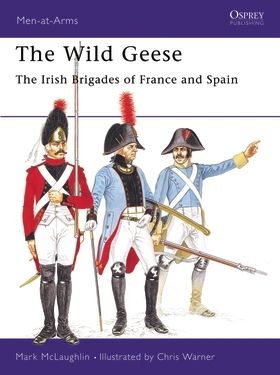

L’époque moderne voit une orientation encore plus marquée vers l’est à travers le service militaire. Après les défaites de la noblesse catholique irlandaise au XVIIe siècle — notamment après la guerre de Guillaume et le traité de Limerick en 1691 — des dizaines de milliers de soldats irlandais, collectivement appelés « Oies sauvages », ont quitté l’île pour servir dans des armées étrangères. Si la France a accueilli le plus grand contingent, l’Empire russe s’est montré particulièrement attractif au XVIIIe siècle. L'armée russe, en pleine modernisation sous Pierre le Grand et ses successeurs, offrait une progression rapide, un salaire important et une relative tolérance religieuse aux officiers catholiques qualifiés. La figure irlandaise la plus célèbre dans ce contexte est le maréchal de camp Pierre (Pyotr Petrovitch) Lacy, né en 1678 près de Kilmallock, dans le comté de Limerick.

L’époque moderne voit une orientation encore plus marquée vers l’est à travers le service militaire. Après les défaites de la noblesse catholique irlandaise au XVIIe siècle — notamment après la guerre de Guillaume et le traité de Limerick en 1691 — des dizaines de milliers de soldats irlandais, collectivement appelés « Oies sauvages », ont quitté l’île pour servir dans des armées étrangères. Si la France a accueilli le plus grand contingent, l’Empire russe s’est montré particulièrement attractif au XVIIIe siècle. L'armée russe, en pleine modernisation sous Pierre le Grand et ses successeurs, offrait une progression rapide, un salaire important et une relative tolérance religieuse aux officiers catholiques qualifiés. La figure irlandaise la plus célèbre dans ce contexte est le maréchal de camp Pierre (Pyotr Petrovitch) Lacy, né en 1678 près de Kilmallock, dans le comté de Limerick.  Son contemporain, et autre officier d’origine irlandaise, Joseph Cornelius O’Rourke (comte Iosif Kornilovich O’Rourke) (portrait), a également atteint un haut rang, en tant que commandant la cavalerie lors des guerres napoléoniennes. Ces carrières illustrent non seulement la réussite individuelle, mais attestent aussi d'un modèle plus large: l’Irlande a fourni un nombre disproportionné de hauts gradés à l’armée russe au XVIIIe et au début du XIXe siècle, intégrant des familles militaires irlandaises dans la société impériale russe.

Son contemporain, et autre officier d’origine irlandaise, Joseph Cornelius O’Rourke (comte Iosif Kornilovich O’Rourke) (portrait), a également atteint un haut rang, en tant que commandant la cavalerie lors des guerres napoléoniennes. Ces carrières illustrent non seulement la réussite individuelle, mais attestent aussi d'un modèle plus large: l’Irlande a fourni un nombre disproportionné de hauts gradés à l’armée russe au XVIIIe et au début du XIXe siècle, intégrant des familles militaires irlandaises dans la société impériale russe.

Arthur Griffith (photo) et d’autres penseurs du Sinn Féin, dès les premières années, s’étaient inspirés de la monarchie austro-hongroise et des campagnes d’autonomie de la Hongrie. Plus tard, durant les Troubles, des comparaisons régulières étaient faites entre l’Irlande du Nord et le Kosovo, Chypre ou les États baltes sous domination soviétique.

Arthur Griffith (photo) et d’autres penseurs du Sinn Féin, dès les premières années, s’étaient inspirés de la monarchie austro-hongroise et des campagnes d’autonomie de la Hongrie. Plus tard, durant les Troubles, des comparaisons régulières étaient faites entre l’Irlande du Nord et le Kosovo, Chypre ou les États baltes sous domination soviétique.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

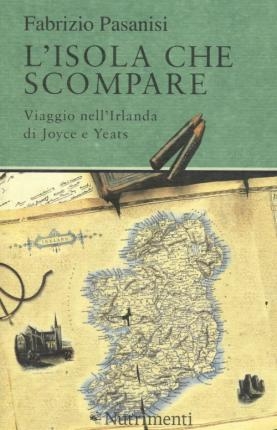

Dans L'isola che scompare (L'île qui disparaît), Fabrizio Pasanisi souligne le lien organique entre l'Irlande et ses chantres. Dans son livre, qui mêle chroniques de voyage et excursions dans l'histoire, Pasanisi exprime un véritable acte d'amour pour la terre des landes vertes, une île "traversée par des histoires, pas moins que l'Italie, des histoires qui viennent de la terre, des histoires qui remplissent l'air", entre une pluie et une autre, des histoires qui naissent de la fantaisie et de la vie - et où d'autre -, et qui restent pour nous, qui allons là-bas, et reconnaissons les lieux, les personnages, dans un visage, entre les rives d'une rivière".

Dans L'isola che scompare (L'île qui disparaît), Fabrizio Pasanisi souligne le lien organique entre l'Irlande et ses chantres. Dans son livre, qui mêle chroniques de voyage et excursions dans l'histoire, Pasanisi exprime un véritable acte d'amour pour la terre des landes vertes, une île "traversée par des histoires, pas moins que l'Italie, des histoires qui viennent de la terre, des histoires qui remplissent l'air", entre une pluie et une autre, des histoires qui naissent de la fantaisie et de la vie - et où d'autre -, et qui restent pour nous, qui allons là-bas, et reconnaissons les lieux, les personnages, dans un visage, entre les rives d'une rivière".

- Pierre Joannon : Navré de vous décevoir ! Aucune goutte de sang irlandais ne coulait dans mes veines jusqu’à une date récente. En 1997, le Taoiseach(Premier ministre) de l’époque a dû sans doute estimer qu’il y avait là une lacune à combler, et il me fit octroyer la nationalité irlandaise, une reconnaissance dont je ne suis pas peu fier. On peut en tirer deux observations : que l’Irlande sait reconnaître les siens, et qu’on peut choisir ses racines au lieu de se contenter de les recevoir en héritage ! D’où me vient cette passion pour l’Irlande ? D’un voyage fortuit effectué au début des années soixante. J’ai eu le coup de foudre pour les paysages du Kerry et du Connemara qui correspondaient si exactement au pays rêvé que chacun porte en soi sans toujours avoir la chance de le rencontrer. Et le méditerranéen que je suis fut immédiatement séduit par ce peuple de conteurs disert, roublard et émouvant, prompt à passer du rire aux larmes avec un bonheur d’expression qui a disparu dans nos sociétés dites évoluées. L’histoire de cette île venait à point nommé répondre à certaines interrogations qui étaient les miennes au lendemain de la débâcle algérienne. Je me mis à lire tous les ouvrages qui me tombaient sous la main, tant en français qu’en anglais. Etudiant en droit, je consacrais ma thèse de doctorat d’Etat à la constitution de l’Etat Libre d’Irlande de 1922 et à la constitution de l’Eire concoctée par Eamon de Valera en 1937. Un premier livre sur l’Irlande, paru aux Editions Plon grâce à l’appui bienveillant de Marcel Jullian, me valut une distinction de l’Académie Française. A quelques temps de là, le professeur Patrick Rafroidi qui avait créé au sein de l’Université de Lille un Centre d’études et de recherches irlandaise unique en France, m’offrit de diriger avec lui la revue universitaire Etudes Irlandaises. En acceptant, je ne me doutais guère que j’en assumerai les fonctions de corédacteur en chef pendant vingt-huit ans. Je publiais, dans le même temps plusieurs ouvrages sur le nationalisme irlandais, sur le débarquement des Français dans le comté de Mayo en 1798, sur de Gaulle et ses rapports avec l’Irlande dont étaient originaires ses ancêtres Mac Cartan, sur Michael Collins et la guerre d’indépendance anglo-irlandaise de 1919-1921, sur John Hume et l’évolution du processus de paix nord-irlandais. J’organisais également plusieurs colloques sur la Verte Erin à la Sorbonne, au Collège de France, à l’UNESCO, à l’Académie de la Paix et de la Sécurité Internationale et à l’Université de Nice. Enfin, en 1989, je pris l’initiative de créer la branche française de la Confédération des Ireland Funds, la plus importante organisation internationale non gouvernementale d’aide à l’Irlande réunissant à travers le monde Irlandais de souche, Irlandais de la diaspora et amis de l’Irlande. Vecteur privilégié de l’amitié entre nos deux pays, l’Ireland Fund de France que je préside distribue des bourses à des étudiants des deux pays, subventionne des manifestations culturelles d’intérêt commun et participe activement à l’essor des relations bilatérales dans tous les domaines. Ainsi que vous pouvez le constater, l’Irlande a fait boule de neige dans ma vie, sans que cela ait été le moins du monde prémédité. Le hasard fait parfois bien les choses.

- Pierre Joannon : Navré de vous décevoir ! Aucune goutte de sang irlandais ne coulait dans mes veines jusqu’à une date récente. En 1997, le Taoiseach(Premier ministre) de l’époque a dû sans doute estimer qu’il y avait là une lacune à combler, et il me fit octroyer la nationalité irlandaise, une reconnaissance dont je ne suis pas peu fier. On peut en tirer deux observations : que l’Irlande sait reconnaître les siens, et qu’on peut choisir ses racines au lieu de se contenter de les recevoir en héritage ! D’où me vient cette passion pour l’Irlande ? D’un voyage fortuit effectué au début des années soixante. J’ai eu le coup de foudre pour les paysages du Kerry et du Connemara qui correspondaient si exactement au pays rêvé que chacun porte en soi sans toujours avoir la chance de le rencontrer. Et le méditerranéen que je suis fut immédiatement séduit par ce peuple de conteurs disert, roublard et émouvant, prompt à passer du rire aux larmes avec un bonheur d’expression qui a disparu dans nos sociétés dites évoluées. L’histoire de cette île venait à point nommé répondre à certaines interrogations qui étaient les miennes au lendemain de la débâcle algérienne. Je me mis à lire tous les ouvrages qui me tombaient sous la main, tant en français qu’en anglais. Etudiant en droit, je consacrais ma thèse de doctorat d’Etat à la constitution de l’Etat Libre d’Irlande de 1922 et à la constitution de l’Eire concoctée par Eamon de Valera en 1937. Un premier livre sur l’Irlande, paru aux Editions Plon grâce à l’appui bienveillant de Marcel Jullian, me valut une distinction de l’Académie Française. A quelques temps de là, le professeur Patrick Rafroidi qui avait créé au sein de l’Université de Lille un Centre d’études et de recherches irlandaise unique en France, m’offrit de diriger avec lui la revue universitaire Etudes Irlandaises. En acceptant, je ne me doutais guère que j’en assumerai les fonctions de corédacteur en chef pendant vingt-huit ans. Je publiais, dans le même temps plusieurs ouvrages sur le nationalisme irlandais, sur le débarquement des Français dans le comté de Mayo en 1798, sur de Gaulle et ses rapports avec l’Irlande dont étaient originaires ses ancêtres Mac Cartan, sur Michael Collins et la guerre d’indépendance anglo-irlandaise de 1919-1921, sur John Hume et l’évolution du processus de paix nord-irlandais. J’organisais également plusieurs colloques sur la Verte Erin à la Sorbonne, au Collège de France, à l’UNESCO, à l’Académie de la Paix et de la Sécurité Internationale et à l’Université de Nice. Enfin, en 1989, je pris l’initiative de créer la branche française de la Confédération des Ireland Funds, la plus importante organisation internationale non gouvernementale d’aide à l’Irlande réunissant à travers le monde Irlandais de souche, Irlandais de la diaspora et amis de l’Irlande. Vecteur privilégié de l’amitié entre nos deux pays, l’Ireland Fund de France que je préside distribue des bourses à des étudiants des deux pays, subventionne des manifestations culturelles d’intérêt commun et participe activement à l’essor des relations bilatérales dans tous les domaines. Ainsi que vous pouvez le constater, l’Irlande a fait boule de neige dans ma vie, sans que cela ait été le moins du monde prémédité. Le hasard fait parfois bien les choses. - C. G. :

- C. G. :  - P. J. : Je suis bien en peine de vous répondre. Il existe tant de figures attachantes ou admirables : Parnell, Michael Collins, de Valera, John Hume aujourd’hui. Peut-être ai-je une prédilection pour Theobald Wolfe Tone, ce jeune avocat protestant qui fut, au dix-huitième siècle, « l’inventeur » du nationalisme irlandais après avoir échoué à intéresser les Anglais à un fumeux projet de colonisation. Il voulait émanciper les catholiques, mobiliser les protestants, liquider les dissensions religieuses au profit d’une conception éclairée de la citoyenneté, briser les liens de sujétion à l’Angleterre. Artisan de l’alliance franco-irlandaise il a laissé un merveilleux journal narrant ses aventures et ses intrigues dans le Paris du Directoire. On y découvre un jeune homme curieux, gai, aimant les femmes et le bon vin, fasciné par le théâtre et les défilés militaires, enthousiasmé par Hoche et beaucoup moins par Bonaparte. Capturé par les Anglais à la suite du piteux échec d’une tentative de débarquement français en Irlande, il sollicita de la cour martiale qui le jugeait la faveur d’être passé par les armes « pour avoir eu l’honneur de porter l’uniforme français ». Elle lui fut refusée : il fut condamné au gibet. La veille de l’exécution, il se trancha la gorge avec un canif et agonisa toute une semaine avant d’expirer le 19 novembre 1798.

- P. J. : Je suis bien en peine de vous répondre. Il existe tant de figures attachantes ou admirables : Parnell, Michael Collins, de Valera, John Hume aujourd’hui. Peut-être ai-je une prédilection pour Theobald Wolfe Tone, ce jeune avocat protestant qui fut, au dix-huitième siècle, « l’inventeur » du nationalisme irlandais après avoir échoué à intéresser les Anglais à un fumeux projet de colonisation. Il voulait émanciper les catholiques, mobiliser les protestants, liquider les dissensions religieuses au profit d’une conception éclairée de la citoyenneté, briser les liens de sujétion à l’Angleterre. Artisan de l’alliance franco-irlandaise il a laissé un merveilleux journal narrant ses aventures et ses intrigues dans le Paris du Directoire. On y découvre un jeune homme curieux, gai, aimant les femmes et le bon vin, fasciné par le théâtre et les défilés militaires, enthousiasmé par Hoche et beaucoup moins par Bonaparte. Capturé par les Anglais à la suite du piteux échec d’une tentative de débarquement français en Irlande, il sollicita de la cour martiale qui le jugeait la faveur d’être passé par les armes « pour avoir eu l’honneur de porter l’uniforme français ». Elle lui fut refusée : il fut condamné au gibet. La veille de l’exécution, il se trancha la gorge avec un canif et agonisa toute une semaine avant d’expirer le 19 novembre 1798.

Au total, 691 soldats ont été tués par la PIRA (dont 197 UDR) et 6 par les loyalistes protestants. De leurs côté, les militaires ont abattus 121 PIRA, 10 loyalistes et 170 civils. La PIRA a tué 1457 civils dont, par règlements de compte, 162 autres « républicains » (c’est-à-dire plus que l’armée), et 28 loyalistes. Ces derniers ont tués 1071 civils.

Au total, 691 soldats ont été tués par la PIRA (dont 197 UDR) et 6 par les loyalistes protestants. De leurs côté, les militaires ont abattus 121 PIRA, 10 loyalistes et 170 civils. La PIRA a tué 1457 civils dont, par règlements de compte, 162 autres « républicains » (c’est-à-dire plus que l’armée), et 28 loyalistes. Ces derniers ont tués 1071 civils.

En 1625, une proclamation officielle ordonna aux prisonniers irlandais d’être rassemblés et vendus comme esclaves aux planteurs anglais. Entre 1629 et 1632, un grand nombre d’Irlandais, hommes et femmes, furent envoyés en Guyane, à Antiqua et à Montserrat. En 1637, environ 69 % de la population de Montserrat était constituée d’esclaves irlandais. Il fallait acheter de nouveaux esclaves, de 20 à 50 livres sterling, des esclaves irlandais capturés et vendus pour 900 livres de coton. Les Irlandais sont devenus la plus grande source d’esclaves pour les marchands d’esclaves anglais.

En 1625, une proclamation officielle ordonna aux prisonniers irlandais d’être rassemblés et vendus comme esclaves aux planteurs anglais. Entre 1629 et 1632, un grand nombre d’Irlandais, hommes et femmes, furent envoyés en Guyane, à Antiqua et à Montserrat. En 1637, environ 69 % de la population de Montserrat était constituée d’esclaves irlandais. Il fallait acheter de nouveaux esclaves, de 20 à 50 livres sterling, des esclaves irlandais capturés et vendus pour 900 livres de coton. Les Irlandais sont devenus la plus grande source d’esclaves pour les marchands d’esclaves anglais. De 1600 à 1699, peu de gens comprennent que plus d’Irlandais étaient vendus comme esclaves que d’Africains.

De 1600 à 1699, peu de gens comprennent que plus d’Irlandais étaient vendus comme esclaves que d’Africains.

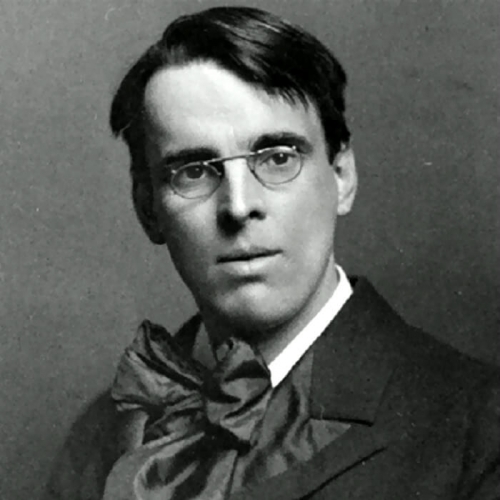

Despite cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as an artist as well as a man.

Despite cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as an artist as well as a man. Despite some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions made to the arts. Despite his

Despite some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions made to the arts. Despite his

At an early age Yeats became involved in mysticism which would prove controversial his whole life. Kodani explains, “The early poetry of William Butler Yeats was very much bound up with the forces and interests of his early years. Many of these influences — such as that of Maud Gonne, his father, and his own mystic studies — have been elucidated by some careful scholarship.” Yeats’ writing was influenced by his study of mysticism. He joined the Theosophical Society as his immediate family’s tradition was not very religious. Later he “became interested in esoteric philosophy, and in 1890 was initiated into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn” (Seymour-Smith). He would pursue mystical philosophy the rest of his life to a greater or lesser degree.

At an early age Yeats became involved in mysticism which would prove controversial his whole life. Kodani explains, “The early poetry of William Butler Yeats was very much bound up with the forces and interests of his early years. Many of these influences — such as that of Maud Gonne, his father, and his own mystic studies — have been elucidated by some careful scholarship.” Yeats’ writing was influenced by his study of mysticism. He joined the Theosophical Society as his immediate family’s tradition was not very religious. Later he “became interested in esoteric philosophy, and in 1890 was initiated into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn” (Seymour-Smith). He would pursue mystical philosophy the rest of his life to a greater or lesser degree.