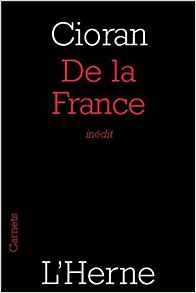

Emil Cioran

De la France

Paris: L’Herne, 2015

This is a strange, vile little book as only Emil Cioran [2] knew how to produce. It was only recently published, in both the original Romanian and in French translation,[1] [3] having been written in 1941 and left to languish for decades in some cardboard box in the Cioran archives. Cioran wrote the book in the wake of France’s pathetic defeat in 1940, inspired by his conversations in Parisian cafés and his bicycling through the villages of the French countryside. Contemporary political events are quite understated, however. For Cioran, there is no question of engaging in puerile journalism; in his view, France’s decay was many centuries in the making.

I first read the book some time ago and remembered nothing except a feeling of revulsion. I recently reread it, this time taking notes. As so often with Cioran, when I gather my notes, my initial revulsion gives way as I see the bigger picture and glimmers of hope, and the work ends up being strangely endearing to me.

I don’t know if the author ever meant for the text, which was written in pencil, to be published at all, let alone in its current form. It seems likely it was written in a few inspired bursts of Cioran’s brilliant and morbid Muse. It is a conversion note. Before 1941, Cioran thought in German, had wished he could have been German, and wrote in Romanian, oscillating between despair and the mad hope that a new barbarism could save Romania from irrelevance and Europe from decadence. After 1945, Cioran had settled into his Parisian home and would henceforth write exclusively in French, as a “lucid” aesthete of nihilism and decline.

Why would someone want such an intellectual destiny for oneself? On France explains it. This is a prolonged meditation upon France, her greatness, vanity, and decay, a book-long portrait of the past glories and the steady and pathetic decline of a great nation. Cioran has in fact fallen in love with his adoptive land; it is indeed a love letter. His prose is often overwritten, but quite insightful: “I perceive France rightly by all that is rotten within me” (40). France is decadent, lifeless, and over-intellectual, just like himself. The book opens with an apt anonymous quotation in French: “Collection d’exagérations maladives” (a collection of sickly/obsessive exaggerations). Rest assured there is a point to all of this, if one bears with it.

Cioran, like Nietzsche, writes with a kind of visceral identification with human history and the evolution of our consciousness as recorded in our literature and philosophy. For Cioran, how could one live without being part of a great nation? For him, a nation is a social, linguistic, and ethnic reality culminating in a shared psychic reality; a great nation is an agent influencing the course of human history, rather than a collection of individuals. A nation is a kind of conversation, a shared mind, extending across the centuries; at the same time, nations are equally mortal and artificial creations. Hence for Cioran, “France,” “Germany,” and “Romania” are entities which are at once conventional and whose potentialities and defects are intimately felt, about which the stakes could not be higher.

Cioran, like Nietzsche, writes with a kind of visceral identification with human history and the evolution of our consciousness as recorded in our literature and philosophy. For Cioran, how could one live without being part of a great nation? For him, a nation is a social, linguistic, and ethnic reality culminating in a shared psychic reality; a great nation is an agent influencing the course of human history, rather than a collection of individuals. A nation is a kind of conversation, a shared mind, extending across the centuries; at the same time, nations are equally mortal and artificial creations. Hence for Cioran, “France,” “Germany,” and “Romania” are entities which are at once conventional and whose potentialities and defects are intimately felt, about which the stakes could not be higher.

Cioran’s actual observations on France can be stereotypical or overwritten, but they are often on point and insightful. France had been the quintessential nation, a historical agent like no other, “a nation afflicted with good fortune” (28), which had known a stable and “regular” development (unlike the stagnation of the Balkans, or the erratic history of Germany and Russia). France was a nation which had never been “humiliated by comparisons,” whose people had never felt themselves to be “deracinated” by foreign influences, who had never felt the material or psychological need to emigrate (27). France was a world unto itself, psychologically self-sufficient, and in that sense strangely provincial, at the same time setting the tone for the entire world: “France – like ancient Greece – has been a universal province” (24). The nation could happily develop at her own, leisurely pace, for she was the world.

In this sense, all of Europe, and indeed much of the world, existed in France’s shadow. For all those formless populaces which wanted to be nations, France set the tone for what was “normal.” France had been the “soul of Europe,” a cultural and even political hegemon. Cioran delights in the decline of the “Grande Nation”: “From the Frenchmen of the Crusades, they have become the Frenchmen of the kitchen and the bistrot: bien-être and boredom” (53).

I recently had reason to observe that I don’t know what it is like to have been born in a second-rate or failed nation. France’s (and the West’s) standard-setting “normality” is in fact highly exceptional [4].

By the time of the Enlightenment, French confidence was also grounded in a belief in reason and progress. This was an “acosmic” culture not troubled by the sublimity and dread of metaphysics, too comfortable in reason, a formal classicism, and an “anti-Dionysian” (80) culture of the head, not of the heart,[2] [5] and committed to the “sterile perfection” of writing (24). It became the nation of self-satisfied Alexandrianism.

All that was over and done with. In the late Middle Ages, France had wavered “between the monastery and the salon” (17), before decisively opting for the latter. The French, since the Enlightenment and in particular during the Revolution, were a perfect example of the weakness of “reason” as a guide for a people. France had degenerated from a nation into a mere populace of selfish individualists, hence sterile, and long given to chatter, overrefinement, and gastronomy (one appreciates the overgeneralizations here). The French gave no place to the unconscious, they were not “deep,” and they had become skeptical and unwilling to die for any ideal (38). Because at this time Cioran seems to only have cared for intensity of feeling and belief, he sees the only remaining vitality left in France in Communism and the working class, although her “revolutionary career” was probably over, anyway (73; hence also some Slavophile sentiments, since Cioran never really distinguished between Russians and Communism, 41).

Cioran, a voracious reader with a vast intellectual culture, is extremely critical of French thought and culture throughout history. Cioran foresees a great convergence: France’s bourgeois decadence indicates where all the other nations are heading, and by that decadence she will also really become a “normal” country, as afflicted by doubt and inferiority complexes as all the rest (45, 49). Cioran writes implausibly, “Her decline, obvious for almost a century, has not been opposed by any of her sons with a desperate protest” (63).

Cioran, a voracious reader with a vast intellectual culture, is extremely critical of French thought and culture throughout history. Cioran foresees a great convergence: France’s bourgeois decadence indicates where all the other nations are heading, and by that decadence she will also really become a “normal” country, as afflicted by doubt and inferiority complexes as all the rest (45, 49). Cioran writes implausibly, “Her decline, obvious for almost a century, has not been opposed by any of her sons with a desperate protest” (63).

By this point, one could fairly accuse the wretch Cioran of sadism. Some kids like to tear the wings off of flies, others just like to watch a once-beautiful flower slowly rot from blight.

Cioran has perhaps only one unambiguously positive thing to say about France, the embrace of fleeting beauty:

France’s divinity: Taste. Good taste.

According to which the world – to exist – must please; must be well-made; consolidate itself aesthetically; have limits; be a graspable enchantment; a sweet flowering [fleurissment] of finitude. (14-15)

He observes that France is “the country of the phenomenon in itself,” of impression, before adding, “If appearances are everything, France is right” (78). Very Zen and very true, no? If life is but a succession of fleeting moments, let them be beautiful.

Cioran luxuriates in France’s decay, and some of the passages are frankly revolting in embellishing – as Alain Soral has complained [6] – spiritual and civilizational rot:

[France] can only live up to [her past] if she accepts her end with style, by masterfully refining a crepuscular culture, by extinguishing herself with intelligence and even with splendor – not without corrupting the freshness of her neighbors or of the world through her decadent infiltrations and dangerous insinuations. (47-48)

There are fecund disintegrations and sterile ones. A great civilization which provincializes itself diminishes its spiritual volume; but, when it spreads the elements of its dissolution, when it universalizes its failure, the twilight retains some symbols of the mind and saves the appearance of nobility. (75)

He also writes, “Of France’s twilight we can only speak in aesthetic terms; we do not feel it, and the French do not feel it either” (59). Well, perhaps a metic could feel this way, but not a Frenchman raised in the knowledge that his country was a great nation among the lights of the world, passed down to us as a sacred patrimony by the sacrifice of millions of French soldiers and peasants. Let us recall Charles de Gaulle’s famous words:

All my life, I have had a certain idea of France. I am inspired in this as much by sentiment as by reason. . . . I instinctively have the impression that Providence has created her for consummate achievements or exemplary misfortunes. If mediocrity marks her deeds and actions, however, I have the feeling of an absurd anomaly, attributable to the faults of the French and not to the genius of the fatherland. But also, the positive side of my mind convinces me that France is only truly herself when she is at the first rank; that only vast enterprises can compensate for the ferments of dispersion which her people carries; that our country, as it is, among the others, as they are us, must, under penalty of death, aim high and stand tall. In short, by my lights, France cannot be France without greatness.

Let it be said that Charles de Gaulle, for all his failures [7], passed this conviction on to the more earnest and impressionable minds of the younger generation through this myth – those who only-too-naïvely took their elders’ words at face value, and who could therefore only be shocked by the nation’s decomposition and slouching into mediocrity. And are de Gaulle’s words not also true, to a great extent, for Europeans in general, who always yearn to dedicate themselves heart and soul to a great cause, without which they are prone to living like dogs? And I cannot tell you how many idealistic young Europeans I have met, who are among the best of our race, who dedicate themselves to the Third World, for there can still be found struggle, sacrifice, and emotional depth and intensity, which can only contrast with the superficiality and barrenness – a rare spiritual oblivion – of coddled life in the post-war West.

I can see a point in Cioran’s musing, but there is also something disgusting – and in some respects simply noxious – for both France and Europe. Cioran, in fact, seems torn: generally favoring belief and fanaticism as the antithesis of decadence (hence sympathy for Hitlerism and Bolshevism), but occasionally observing that perhaps Europe needs a bit of doubt, which France could bring (65).

Cioran is convinced of the catastrophic effects of the illusions of “reason” and “progress.” But if France, the pioneer-nation of the Enlightenment, would cease to believe in such follies . . . surely Western man could finally awaken from these self-satisfied, sterilizing slogans! Or, at least, Cioran believes he, as an “intellectual vampire” (60), could be a lucid and fecund writer in this context. He leapfrogs centuries of history:

Hailing from primitive lands, the Wallachian underworld, with the pessimism of youth, and then arriving in an overly ripe civilization, what a source of shivers before such a contrast! Without a past amidst an enormous past . . . From the pasture to the salon, from the shepherd to Alcibiades! (66)

Hence, Cioran loves France because she has fallen from self-assured greatness into a doubt and pessimism much like his own. Whereas he had previously loved Hitlerian Germany for its irrational faith, he now presents France as a mirror image of himself, an entire nihilist country in which he might be able to achieve the highest lucidity:

An entire country which no longer believes in anything, what an exalting and degrading spectacle! To hear them, from the lowest of citizens to the most lucid, say the obvious with detachment: “La France n’exist plus,” “Nous sommes finis,” “Nous n’avons plus d’avenir, “Nous sommes un pays en décadence,” what a reinvigorating lesson, when you are no longer a devotee of delusions! (69)

France is “a consoling space” for Cioran: “With what impatience I have awaited this outcome, so fertile for melancholic inspiration!” (70). The wandering and soon-to-be stateless Cioran wants to limit himself to a particular culture and place: “He who embraces too much falsifies the world, but in the first instance, himself . . . A great soul enclosed in the French forms, what a fecund type of humanity!” (87). France’s comfortable decadence will shield Cioran from his own excesses: “Let her measure cure us of pathetic and fatal wanderings” (32), “A country’s lack of life will protect us against the dangers of life” (88). Crepuscular France will finally give Cioran the opportunity to be in harmony with his time: “Alexandrianism is erudite debauchery as a system, theoretical breathing at the twilight, a moaning of concepts – and the only moment when the soul can harmonize its darkness with the objective unfolding of the culture” (70).

France is “a consoling space” for Cioran: “With what impatience I have awaited this outcome, so fertile for melancholic inspiration!” (70). The wandering and soon-to-be stateless Cioran wants to limit himself to a particular culture and place: “He who embraces too much falsifies the world, but in the first instance, himself . . . A great soul enclosed in the French forms, what a fecund type of humanity!” (87). France’s comfortable decadence will shield Cioran from his own excesses: “Let her measure cure us of pathetic and fatal wanderings” (32), “A country’s lack of life will protect us against the dangers of life” (88). Crepuscular France will finally give Cioran the opportunity to be in harmony with his time: “Alexandrianism is erudite debauchery as a system, theoretical breathing at the twilight, a moaning of concepts – and the only moment when the soul can harmonize its darkness with the objective unfolding of the culture” (70).

In short, Cioran seizes the opportunity to join a decadent, highly intellectual nation, so as to explore the depths of nihilism and see where one emerges. I can appreciate this kind of personal and philosophical project.

Cioran carves a role out for himself as a fertilizing maggot in the corpse of French civilization. Cioran, not disinterestedly, affirms that the greatness of a nation can be measured by its ability to inspire metics to join and serve it, which I suppose is partly true (92-94). Cioran then foresees his own destiny in this new home:

What would I do if I were French? I would rest in Cynicism. (40)

France needs a pathetic and cynical Paul Valéry, an absolute artist of the void and of lucidity. (48)

My destiny is to wrap myself in the dregs of civilizations. How can I show my strength except by resisting in the midst of rot? The relationship between barbarism and neurasthenia balances this formula. An aesthete of the twilight of cultures, I turn my gaze of storm and dreams upon the dead waters of the mind . . . (65)

To refuse to go extinct, even though we have delighted in the inevitable march towards extinction. (82)

A kind of moribund fury lies in the aesthetes of decadence. (84)

Cioran affirms that decadence can only be overcome, not through sentimental nostalgia or insincere conservatism, but by uncompromisingly going deeper . . . perhaps then nihilism will be transcended? That which is falling ought to be pushed, that which doesn’t kill us, and so on.

On France seems to be a book-long philosophical exercise. There are well-established traditions in this kind of morbid meditation in both Stoicism and Buddhism, schools which strongly resonated with Cioran. In Stoic analysis, one breaks down an object to its most essential, unappetizing forms so as to overcome our desires with objectivity. As Marcus Aurelius wrote in his Meditations:

When you have savories and fine dishes set before you, you will gain an idea of their nature if you tell yourself that this is the corpse of a fish, and that the corpse of a bird or a pig; or again, that fine Falernian wine is merely grape juice, and this purple robe some sheep’s wool dipped in the blood of a shellfish; and as for sexual intercourse, it is the friction of a piece of gut and, following a sort of convulsion, the expulsion of some mucus. Thoughts such as these reach through to the things themselves and strike to the heart of them, allowing us to see them as they truly are. So follow this practice throughout your life, and where things seem most worthy of your approval, lay them naked, and see how cheap they are, and strip them of the pretenses of which they are so vain. (Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 6.13)

The Buddhists attribute a similar meditative exercise to Gautama: contemplating the various aspects of our being (mind, body, actions, including defecation and urination), breaking down our body into parts, and indeed contemplating our body subject to various degrees of decomposition (notably in the Satipatṭhāna Sutta). By this, one attains a certain objectivity and imperviousness, one is learning to look the truth in the face without flinching.

On France appears to be the fruit of this kind of philosophical exercise. By stripping France of her pretensions and even the usual dignities necessary for a nation or an individual’s self-respect, Cioran sees his new home objectively. This is indeed one of Cioran’s “nay-saying, corrosive books,” a challenge, the overcoming of which will make us stronger.

In the 1920s and ’30s, no one denied the decadence which already afflicted the France of the Third Republic. No one today can deny that all Europe is decadent, unashamed of her impotence and dedicated to the most impoverished materialist and humanitarian principles, consecrated to the Last Man foreseen by Nietzsche, and with no end in sight. Given all this, Cioran’s observations and his challenge remain deeply relevant to us. Cioran is torn, but points to the need for decidedly modern barbarians: “I dream of a culture of oracles in logic, of lucid Pythias . . . and of a man who would control his reflexes with a supplement of life, and not through austerity” (89).

En guise de conclusion, I recall the words of the Buddha:

Just as a sweet-smelling and pleasant lotus grows on a heap of refuse flung on the high road, so a disciple of the Fully Awakened One shines resplendent in wisdom among the blind multitude, the refuse of beings. (Dhammapada, 58-59)

Some translated excerpts from this book will be published at Counter-Currents in the coming days.

Notes

[1] [8] The French edition is incidentally quite elegant and has been printed using blue ink.

[2] [9] Cioran often writes of nations having or lacking vigor “in the blood,” using this word strangely more in a psychological than hereditarian sense.

Le nouveau président vénézuélien désavoua rapidement ce nationaliste-révolutionnaire péroniste et anti-atlantiste radical et le fit expulser dès 1999. Les idées tercéristes de Ceresole indisposaient les nombreux progressistes gravitant autour d’Hugo Chavez. Si celui-ci appliqua en diplomatie une conception assez proche des idées de Ceresole (hostilité aux États-Unis et au libéralisme prédateur, pan-américanisme institutionnel, rapprochement avec la Russie, l’Iran, le Bélarus et la Chine, soutien au Hezbollah et à la cause palestinienne), il gâcha tous ces atouts en politique intérieure comme l’avait prévenu dès 2007 Raul Baduel, son vieux frère d’arme entré ensuite dans un « chavisme d’opposition » et longtemps incarcéré.

Le nouveau président vénézuélien désavoua rapidement ce nationaliste-révolutionnaire péroniste et anti-atlantiste radical et le fit expulser dès 1999. Les idées tercéristes de Ceresole indisposaient les nombreux progressistes gravitant autour d’Hugo Chavez. Si celui-ci appliqua en diplomatie une conception assez proche des idées de Ceresole (hostilité aux États-Unis et au libéralisme prédateur, pan-américanisme institutionnel, rapprochement avec la Russie, l’Iran, le Bélarus et la Chine, soutien au Hezbollah et à la cause palestinienne), il gâcha tous ces atouts en politique intérieure comme l’avait prévenu dès 2007 Raul Baduel, son vieux frère d’arme entré ensuite dans un « chavisme d’opposition » et longtemps incarcéré.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

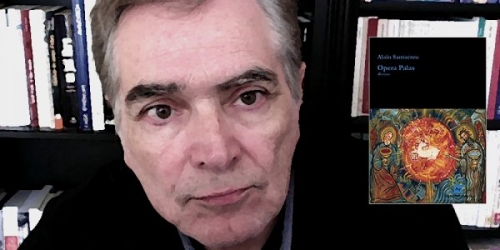

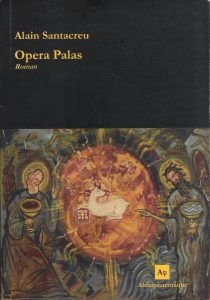

Les personnages de cet essai romanesque (le narrateur travaille sur Opera Palas – belle mise en abyme , le journaliste étatsunien Julius Wood qui fait plus que du journalisme) pratiquent à leur façon l’impersonnalité active. Toutefois, bien que mise en arrière-plan, c’est une œuvre d’art qui focalise l’attention : Le Grand Verre de Marcel Duchamp, aussi connu sous le nom de La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même. Réalisé entre 1915 et 1923 sur du verre (fils de plomb, feuilles et peinture), cette œuvre inachevée et fêlée présente une riche polysémie propice aux interprétations érotiques, psychanalytiques ou ésotériques. C’est dans ce dernier champ qu’intervient principalement Opera Palas.

Les personnages de cet essai romanesque (le narrateur travaille sur Opera Palas – belle mise en abyme , le journaliste étatsunien Julius Wood qui fait plus que du journalisme) pratiquent à leur façon l’impersonnalité active. Toutefois, bien que mise en arrière-plan, c’est une œuvre d’art qui focalise l’attention : Le Grand Verre de Marcel Duchamp, aussi connu sous le nom de La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même. Réalisé entre 1915 et 1923 sur du verre (fils de plomb, feuilles et peinture), cette œuvre inachevée et fêlée présente une riche polysémie propice aux interprétations érotiques, psychanalytiques ou ésotériques. C’est dans ce dernier champ qu’intervient principalement Opera Palas.

Cioran, like Nietzsche, writes with a kind of visceral identification with human history and the evolution of our consciousness as recorded in our literature and philosophy. For Cioran, how could one live without being part of a great nation? For him, a nation is a social, linguistic, and ethnic reality culminating in a shared psychic reality; a great nation is an agent influencing the course of human history, rather than a collection of individuals. A nation is a kind of conversation, a shared mind, extending across the centuries; at the same time, nations are equally mortal and artificial creations. Hence for Cioran, “France,” “Germany,” and “Romania” are entities which are at once conventional and whose potentialities and defects are intimately felt, about which the stakes could not be higher.

Cioran, like Nietzsche, writes with a kind of visceral identification with human history and the evolution of our consciousness as recorded in our literature and philosophy. For Cioran, how could one live without being part of a great nation? For him, a nation is a social, linguistic, and ethnic reality culminating in a shared psychic reality; a great nation is an agent influencing the course of human history, rather than a collection of individuals. A nation is a kind of conversation, a shared mind, extending across the centuries; at the same time, nations are equally mortal and artificial creations. Hence for Cioran, “France,” “Germany,” and “Romania” are entities which are at once conventional and whose potentialities and defects are intimately felt, about which the stakes could not be higher. Cioran, a voracious reader with a vast intellectual culture, is extremely critical of French thought and culture throughout history. Cioran foresees a great convergence: France’s bourgeois decadence indicates where all the other nations are heading, and by that decadence she will also really become a “normal” country, as afflicted by doubt and inferiority complexes as all the rest (45, 49). Cioran writes implausibly, “Her decline, obvious for almost a century, has not been opposed by any of her sons with a desperate protest” (63).

Cioran, a voracious reader with a vast intellectual culture, is extremely critical of French thought and culture throughout history. Cioran foresees a great convergence: France’s bourgeois decadence indicates where all the other nations are heading, and by that decadence she will also really become a “normal” country, as afflicted by doubt and inferiority complexes as all the rest (45, 49). Cioran writes implausibly, “Her decline, obvious for almost a century, has not been opposed by any of her sons with a desperate protest” (63). France is “a consoling space” for Cioran: “With what impatience I have awaited this outcome, so fertile for melancholic inspiration!” (70). The wandering and soon-to-be stateless Cioran wants to limit himself to a particular culture and place: “He who embraces too much falsifies the world, but in the first instance, himself . . . A great soul enclosed in the French forms, what a fecund type of humanity!” (87). France’s comfortable decadence will shield Cioran from his own excesses: “Let her measure cure us of pathetic and fatal wanderings” (32), “A country’s lack of life will protect us against the dangers of life” (88). Crepuscular France will finally give Cioran the opportunity to be in harmony with his time: “Alexandrianism is erudite debauchery as a system, theoretical breathing at the twilight, a moaning of concepts – and the only moment when the soul can harmonize its darkness with the objective unfolding of the culture” (70).

France is “a consoling space” for Cioran: “With what impatience I have awaited this outcome, so fertile for melancholic inspiration!” (70). The wandering and soon-to-be stateless Cioran wants to limit himself to a particular culture and place: “He who embraces too much falsifies the world, but in the first instance, himself . . . A great soul enclosed in the French forms, what a fecund type of humanity!” (87). France’s comfortable decadence will shield Cioran from his own excesses: “Let her measure cure us of pathetic and fatal wanderings” (32), “A country’s lack of life will protect us against the dangers of life” (88). Crepuscular France will finally give Cioran the opportunity to be in harmony with his time: “Alexandrianism is erudite debauchery as a system, theoretical breathing at the twilight, a moaning of concepts – and the only moment when the soul can harmonize its darkness with the objective unfolding of the culture” (70).