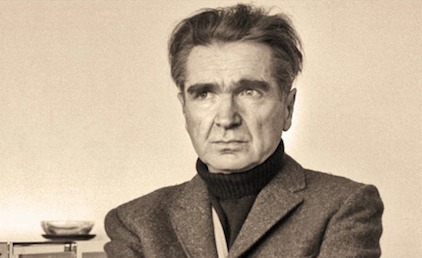

Emil Cioran

Emil Cioran

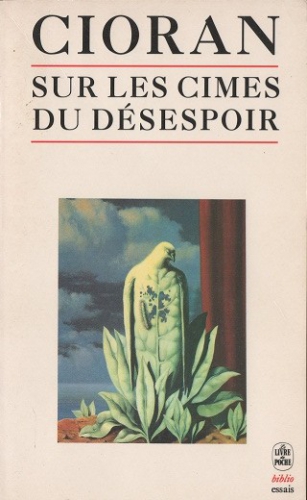

Apologie de la Barbarie: Berlin – Bucharest (1932-1941)

Paris: L’Herne, 2015

This is a very interesting book released by the superior publishing house L’Herne: a collection of Emil Cioran’s articles published in Romanian newspapers, mostly from before the war. Besides becoming a famous aphorist in later years, before the Allied victory, Cioran was still free to be a perceptive and biting cultural critic and political analyst.

While reading the book, I was chiefly interested in understanding the motivations behind Cioran’s support for nationalism and fascism. We can identify a few recurring themes:

- A sense of humiliation at Romania’s underdevelopment, historical irrelevance, and cultural/intellectual dependence with regard to the West: “That is why the Romanian always agrees with the latest author he has read” (22).

- A pronounced Germanophilia, appreciating German artists’ and intellectuals’ intensity, pathos, and diagnostic of Western decadence.

- Frustration with democratic politics as leading selfish individualism and political impotence.

- A marked preference for belief and irrational creativity over sterile rationalism and skepticism.

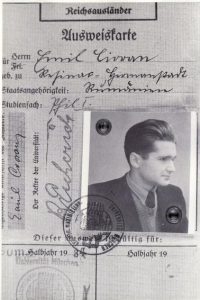

Cioran, who had already been well acquainted with German high culture during his studies in Romania, really took to Hitlerian Germany when he moved in 1933 there on a scholarship from the Humboldt Foundation. He writes:

In Germany, I realized that I was mistaken in believing that one can perfectly integrate a foreign culture. I hoped to identify myself perfectly with the values of German history, to cut my Romanian cultural roots to assimilate completely into German culture. I will not comment here on the absurdity of this illusion. (100)

The influence of Cioran’s German sources clearly shines through, including Nietzsche, Spengler, and Hitler himself.[1] [2] Cioran’s infatuation proved lasting. He wrote in 1937: “I think there are few people – even in Germany – who admire Hitler more than I do” (240).

On one level, Cioran’s politics are eminently realistic, frankly acknowledging the tragic side of human existence. He admires Italian Fascism and especially German National Socialism because these political movements had restored strong beliefs and had heightened the historical level and international power of these nations. If liberties must be trampled upon and certain individuals marginalized for a community to flourish, so be it. On foreign policy, he favors national self-sufficiency and Realpolitik as against dependence upon unstable or sentimental alliances.

Cioran is extremely skeptical of pacifist and universalist movements, convinced that great nations each have their own historical direction. Human history, in his view, would not necessarily converge and ought to remain pluralistic. If Europe was to converge to one culture, this would tragically require the triumph and imposition of one culture on the others. In particular, he believed Franco-German peace would be impossible without the collapse of one nation or the other (little did he suspect both would be crushed). Diversity and a degree of tension between nations and civilizations were good, providing “the essential antinomies which are the basis of life” (98).

Alongside these rather realistic considerations, spoken in a generally detached and level-headed tone, Cioran’s politics and in particular his nationalism were powerfully motivated by a sense of despair at the state of Romania. Cioran viscerally identified with his nation and intensely felt what he considered to be its deficiencies as a bucolic and peripheral culture. He then makes an at once passionate and desperate plea a zealous nationalist and totalitarian dictatorship which could spark Romania’s spark geopolitical, historical, and cultural renewal. Only such a regime, on the German model, could organize the youth and redeem an otherwise irrelevant nation. The continuation of democracy, by contrast, would mean only the disintegration of the nation into a collection of fissiparous and spoiled individuals: “Another period of ‘democracy’ and Romania will inevitably confirm its status of historical accident” (225).

A rare and stimulating combination in Cioran’s writings: unsentimental observation and intense pathos.

A rare and stimulating combination in Cioran’s writings: unsentimental observation and intense pathos.

Cioran’s nationalism was highly idiosyncratic. He writes with amusing condescension of the local tradition of nostalgic and parochial patriotic writing: “To be sure, the geographical nationalism which we have witnessed up to now, with all its literature of patriotic exaltation and its idyllic vision of our historical existence, has its merits and its rights” (150). He was also uninterested in a nationalism as merely a moralistic defensive conservatism, defined merely as the maintenance of the borders of the Greater Romania which, with the annexation of Transylvania, had been miraculously established in the wake of the First World War.

For Cioran nationalism had to serve a great political project, it had to have a set of values and ambitions enabling a great historical flourishing, rather than be merely a sentimental or selfish end in itself. He writes of A. C. Cuza, a prominent politician who made anti-Semitism his signature issue:

Nationalism, as a sentimental formula, lacking in any ideological backbone or political perspectives, has no value. The dishonorable destiny of A. C. Cuza has no other explanation than the agitations of an apolitical man whose fanaticism, which has never gone further than anti-Semitism, was never able to become a fatality for Romania. If we had had no Jews, A. C. Cuza would never have thought of his country. (214)

Similarly, Cioran argues that the embrace of nationalism is dependent on time and purpose:

One is a nationalist only in a given time, when to not be a nationalist is a crime against the nation. In a given time means in a historical moment when everyone’s participation is a matter of conscience. The demands of the historical moment also mean: one is not [only] a nationalist, one is also a nationalist. (149-50)

Cioran was also – at least in this selection of articles – uninterested in Christianity and aggressively rejected Romania’s past and traditions, in favor a revolutionary project of martial organization, planned industrialization, and national independence. For Cioran, Romania needed nothing less than a “national revolution” requiring “a long-lasting megalomania” (154).

All this seems far removed from the agrarian traditionalism and Christian mysticism of Corneliu Zelea Codreanu’s Iron Guard. Cioran did, however, hail the Guard as a Romanian “awakening” and after Codreanu’s murder wrote a moving ode to the Captain [3]. By contrast, Cioran excoriates the consensual Transylvanian politician Iulia Maniu as an ineffectual and corrosive “Balkan buddhist,” peddling “political leukemia” (220).

A friend of mine observed that at least some aspects of Cioran’s program resembles Nicolae Ceaușescu’s later formula: perhaps late Romanian communism did seek to reflect some of the nation’s deep-seated aspirations concerning its place in the world.

One is struck by the contrast between Cioran’s lyricism on Germany, his desperate call to “transfigurate” Romania, and his perfectly lucid and quite balanced assessment of Fascist Italy [4]. There is something quite unreasonable in Cioran’s revolutionary ambitions. Fascism, certainly, is an effective way of instating political stability, steady leadership, and civil peace, annihilating communism, maximizing national power and independence, and educating and systematically organizing the nation according to whatever values you hold dear.

But fascism cannot work miracles. Politics must work with the human material and historical trajectory that one has. That is being true to oneself. To wish for total transformation and the tabula rasa is to invite disaster. Such revolutions are generally an exercise in self-harm. Once the passions and intoxications have settled, one finds the nation stunted and lessened: by civil war, by tyranny, by self-mutilation and deformation in the stubborn in the name of utopian goals. The historic gap with the ‘advanced’ nations is widened further still by the ordeal.

But fascism cannot work miracles. Politics must work with the human material and historical trajectory that one has. That is being true to oneself. To wish for total transformation and the tabula rasa is to invite disaster. Such revolutions are generally an exercise in self-harm. Once the passions and intoxications have settled, one finds the nation stunted and lessened: by civil war, by tyranny, by self-mutilation and deformation in the stubborn in the name of utopian goals. The historic gap with the ‘advanced’ nations is widened further still by the ordeal.

In the case of Romania, I can imagine that a spirited, moderate, and progressive authoritarian regime might have been able to raise the country’s historical level, just as Fascism had in Italy. Romania could aspire to be a Balkan hegemon. Beyond this, raising Romania would have required generations of careful and steady work, not hysterical outbursts, notably concerning population policy. The country had a comparatively low population density – a territory twice the size as England, but with half the population. There was a vigorous and progressive eugenics movement in interwar Romania [5] which also sought to improve the people’s biological stock, but this came to naught.

Another very striking aspect of Cioran’s fascism and nationalism is that he does not take race seriously. He says in his first article written from Germany (November 14, 1933):

If one objects that today’s political orientation [in Germany] is unacceptable, that it is founded on false values, that racism is a scientific illusion, and that German exclusivism is a collective megalomania, I would respond: What does it matter, so long as Germany feels well, fresh, and alive under such a regime?

Reducing National Socialism’s appeal to mere emotional power, although that is important, will certainly puzzle progressive racialists and evolutionary humanists.[2] [6] In the same vein, Cioran occasionally expresses sympathy for communism, because of that ideology’s ability to inspire belief. There is something irresponsible in all this. And yet, living in an order of rot and incoherence, we can only share in Cioran’s hope: “We have no other mission than to work for the intensification of the process of fatal collapse” (51).

One wonders how Cioran’s disenchantment with Hitlerian Germany occurred. The fact that he wrote his conversion note [7]On France [7] in 1941, before the major reversals for the Axis, is certainly intriguing.

Cioran’s comments on Romania’s ineptitude are striking and sadly well in line with the current state of the Balkans. Cioran hailed from Transylvania, which though having a Romanian majority, had significant Saxon and Hungarian minorities and a tradition of Austro-Hungarian government. Cioran contrasts the stolid Saxons with the erratic Romanians, the staid Transylvanian “citizens” with the corrupt “patriots” of the old-Romanian provinces (Wallachia, Moldova). So while he rejected any idea of Romania becoming merely a respectable, prosperous “Switzerland,” Cioran also desired some good old-fashioned (bourgeois?) competence. He indeed calls Transylvania “Romania’s Prussia.”

To this day, besides Bucharest, the wealthier and more functional parts of the country are to be found in Transylvania. In the 2014 presidential elections, there was an eerie overlap [8] between the vote for the liberal-conservative candidate Klaus Iohannes and the historical boundaries of Austria-Hungary.

What I find most stimulating in Cioran is his dialectic between his concerns as a pure intellectual – lucidity, the vanity of things, universal truth – and his recognition of and desire for the intoxicating needs of Life: belief, action in the here-and-now, ruthlessness, and passion. Cioran writes:

The oscillation between preoccupations that could not be further from current events and the need to adopt, within the historical process, an immediate attitude, produces, in the mind of certain contemporary intellectuals, a strange frenzy, a constant irritation, and an exasperating tension. (117)

I was shocked to encounter the following passage and yet the thought had also occurred to me:

In Germany, I began to study Buddhism in order not to be intoxicated or contaminated with Hitlerism. But my meditation on the void brought me to understand, by the contrast, Hitlerism better than did any ideological book. Immediate positivity and the terror of temporal decision, the total lack of transcendence of politics, but especially the bowing before the merciless empire of becoming, all these grow in a dictatorship to the point of exasperation. A suffocating rhythm, alternating with a megalomaniacal breath, gives it a particular psychology. The profile of dictatorship is a monumental chiaroscuro. (233-34)

Nature, ‘red in tooth and claw,’ and the inevitable void: a fertile dialectic, from which we may hope Life with prevail.

Notes

[1] [9] E.g. Cioran observes that fears surrounding Hungary’s ambition to reconquer Transylvania from Romania only existed due to Romania’s own internal political weakness: “[There is an] unacceptable illusion among us according to which foreign relations could compensate for an internal deficiency, whereas in fact the value of these relations depends, at bottom, on our inner strength” (171). A classic Hitlerian point.

[2] [10] Elsewhere, Cioran denounces, in the name of a lucid Realpolitik, overdependence on the unreliable alliance with France and sympathy for the “Latin sister nation” Italy, which was then supporting Hungary: “Concerning affinities of blood and race, who knows how many illusions are not hidden in such beliefs?” (172). Certainly, people have often confused linguistic proximity with actual blood kinship.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Cioran, like Nietzsche, writes with a kind of visceral identification with human history and the evolution of our consciousness as recorded in our literature and philosophy. For Cioran, how could one live without being part of a great nation? For him, a nation is a social, linguistic, and ethnic reality culminating in a shared psychic reality; a great nation is an agent influencing the course of human history, rather than a collection of individuals. A nation is a kind of conversation, a shared mind, extending across the centuries; at the same time, nations are equally mortal and artificial creations. Hence for Cioran, “France,” “Germany,” and “Romania” are entities which are at once conventional and whose potentialities and defects are intimately felt, about which the stakes could not be higher.

Cioran, like Nietzsche, writes with a kind of visceral identification with human history and the evolution of our consciousness as recorded in our literature and philosophy. For Cioran, how could one live without being part of a great nation? For him, a nation is a social, linguistic, and ethnic reality culminating in a shared psychic reality; a great nation is an agent influencing the course of human history, rather than a collection of individuals. A nation is a kind of conversation, a shared mind, extending across the centuries; at the same time, nations are equally mortal and artificial creations. Hence for Cioran, “France,” “Germany,” and “Romania” are entities which are at once conventional and whose potentialities and defects are intimately felt, about which the stakes could not be higher. Cioran, a voracious reader with a vast intellectual culture, is extremely critical of French thought and culture throughout history. Cioran foresees a great convergence: France’s bourgeois decadence indicates where all the other nations are heading, and by that decadence she will also really become a “normal” country, as afflicted by doubt and inferiority complexes as all the rest (45, 49). Cioran writes implausibly, “Her decline, obvious for almost a century, has not been opposed by any of her sons with a desperate protest” (63).

Cioran, a voracious reader with a vast intellectual culture, is extremely critical of French thought and culture throughout history. Cioran foresees a great convergence: France’s bourgeois decadence indicates where all the other nations are heading, and by that decadence she will also really become a “normal” country, as afflicted by doubt and inferiority complexes as all the rest (45, 49). Cioran writes implausibly, “Her decline, obvious for almost a century, has not been opposed by any of her sons with a desperate protest” (63). France is “a consoling space” for Cioran: “With what impatience I have awaited this outcome, so fertile for melancholic inspiration!” (70). The wandering and soon-to-be stateless Cioran wants to limit himself to a particular culture and place: “He who embraces too much falsifies the world, but in the first instance, himself . . . A great soul enclosed in the French forms, what a fecund type of humanity!” (87). France’s comfortable decadence will shield Cioran from his own excesses: “Let her measure cure us of pathetic and fatal wanderings” (32), “A country’s lack of life will protect us against the dangers of life” (88). Crepuscular France will finally give Cioran the opportunity to be in harmony with his time: “Alexandrianism is erudite debauchery as a system, theoretical breathing at the twilight, a moaning of concepts – and the only moment when the soul can harmonize its darkness with the objective unfolding of the culture” (70).

France is “a consoling space” for Cioran: “With what impatience I have awaited this outcome, so fertile for melancholic inspiration!” (70). The wandering and soon-to-be stateless Cioran wants to limit himself to a particular culture and place: “He who embraces too much falsifies the world, but in the first instance, himself . . . A great soul enclosed in the French forms, what a fecund type of humanity!” (87). France’s comfortable decadence will shield Cioran from his own excesses: “Let her measure cure us of pathetic and fatal wanderings” (32), “A country’s lack of life will protect us against the dangers of life” (88). Crepuscular France will finally give Cioran the opportunity to be in harmony with his time: “Alexandrianism is erudite debauchery as a system, theoretical breathing at the twilight, a moaning of concepts – and the only moment when the soul can harmonize its darkness with the objective unfolding of the culture” (70).

From this period until his definitive move to France (1941), Cioran would constantly ideologize his discourse, fight against pacifism as well as skepticism, and promote the fanaticization of the masses and the resort to violence in order to destroy critical thought – convinced of having discovered in Hitlerism a model dictatorship to be urgently imported into his own country. He also sought – with force, lyricism, and aggressiveness – to put before his compatriots the following choice: a mission or despair; the birth of a history or rotting in time’s ash-heap; the transfiguring leap or death . . . He wrote in the February 4, 1934 columns of Vremea:

From this period until his definitive move to France (1941), Cioran would constantly ideologize his discourse, fight against pacifism as well as skepticism, and promote the fanaticization of the masses and the resort to violence in order to destroy critical thought – convinced of having discovered in Hitlerism a model dictatorship to be urgently imported into his own country. He also sought – with force, lyricism, and aggressiveness – to put before his compatriots the following choice: a mission or despair; the birth of a history or rotting in time’s ash-heap; the transfiguring leap or death . . . He wrote in the February 4, 1934 columns of Vremea:

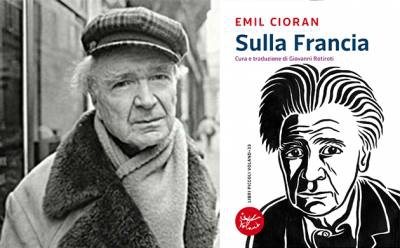

R.R.: Cioran’s first book to be published in Italy was Squartamento (Drawn and quartered) launched by Adelphi in 1981, even though some other titles had already been published in the previous decade by right-wing publishing houses, even if they had not had much repercussion. It was precisely thanks to Adelphi, and to Ceronetti’s wonderful introduction, that the name of Cioran became well-known to the Italian readers. Roberto Calasso is a great cultural player, but he is a rather arrogant person and, I must say, ungallant as well. My encounters with Cioran and Severino, two giants of thought, allowed me to understand how the true greatness is always accompanied by genuine humbleness a gentleness. Virtues which Calasso, in my opinion, lacks – and I say so based on the personal experience I have had with him in more than one occasion. Unfortunately, Volpi left us too early due to a banal accident while riding his bicycle on the Venetian hills (northeast of Italy), not far away from where I live. His intelligence illuminated us for a long a time. In 2002, he wrote a piece on Friedgard Thoma‘s book, Per nulla al mondo, releasing himself once and for all from the choir of censors, who had soon made their apparition. I enjoy recalling this marvellous passage: “Under the influence of passion, Cioran reveals himself. He jeopardizes everything in order to win the game, reveals innermost dimensions of his psyche, surprising features of his character… Attracted by the challenge of the eternal feminine, he allows secret depths of his thought to come to surface: a denuded thought before the feminine look which penetrates him…”

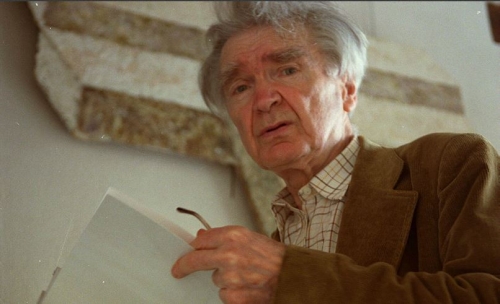

R.R.: Cioran’s first book to be published in Italy was Squartamento (Drawn and quartered) launched by Adelphi in 1981, even though some other titles had already been published in the previous decade by right-wing publishing houses, even if they had not had much repercussion. It was precisely thanks to Adelphi, and to Ceronetti’s wonderful introduction, that the name of Cioran became well-known to the Italian readers. Roberto Calasso is a great cultural player, but he is a rather arrogant person and, I must say, ungallant as well. My encounters with Cioran and Severino, two giants of thought, allowed me to understand how the true greatness is always accompanied by genuine humbleness a gentleness. Virtues which Calasso, in my opinion, lacks – and I say so based on the personal experience I have had with him in more than one occasion. Unfortunately, Volpi left us too early due to a banal accident while riding his bicycle on the Venetian hills (northeast of Italy), not far away from where I live. His intelligence illuminated us for a long a time. In 2002, he wrote a piece on Friedgard Thoma‘s book, Per nulla al mondo, releasing himself once and for all from the choir of censors, who had soon made their apparition. I enjoy recalling this marvellous passage: “Under the influence of passion, Cioran reveals himself. He jeopardizes everything in order to win the game, reveals innermost dimensions of his psyche, surprising features of his character… Attracted by the challenge of the eternal feminine, he allows secret depths of his thought to come to surface: a denuded thought before the feminine look which penetrates him…” R.R.: My book undertakes a theoretical exegesis of Cioran’s thought so as to evince how the problem of Time is the basis for all his meditation. The connective “and” of the title becomes the supporting verb for the thesis I intend to sustain: Time is Destiny. The curse of existence is that of being “incarcerated” in the linearity of time, which stems from a paradisiacal, pre-temporal past, toward a destiny of death and decay. It is, to sum up, a tragic worldview of Greek origin embedded in a Judeo-Christian conception, though deprived of all éscathon. But can we be sure that Cioran dismisses each and every form of salvation? There are two polarities which communicate in my book: Severino’s absolute eternity and Cioran’s explicit nihilism. From Severino’s point of view, one might as well define Cioran’s thought as the becoming aware of nihilism inherent to the Western conception of Time. And in Cioran’s mystical temptation, on the other hand, one may find a sentimental perception of Being which seems to point to the need, the urge, the hope, so to speak, for an overcoming of Western hermeneutics of Becoming and for an ulterior word that is not Negation. The book starts with an account of my three encounters with Aurel, Cioran’s brother, in the years of 1987, 1991 and 1995, and of my two encounters with Emil, in 1988 and 1989. The book also includes all the letters which Cioran wrote to me, plus countless photographs. After the first part, there comes a bio-bibliographical inquiry on his Romanian years, a pioneer work of exhumation at a time when there were no reliable sources on the matter.

R.R.: My book undertakes a theoretical exegesis of Cioran’s thought so as to evince how the problem of Time is the basis for all his meditation. The connective “and” of the title becomes the supporting verb for the thesis I intend to sustain: Time is Destiny. The curse of existence is that of being “incarcerated” in the linearity of time, which stems from a paradisiacal, pre-temporal past, toward a destiny of death and decay. It is, to sum up, a tragic worldview of Greek origin embedded in a Judeo-Christian conception, though deprived of all éscathon. But can we be sure that Cioran dismisses each and every form of salvation? There are two polarities which communicate in my book: Severino’s absolute eternity and Cioran’s explicit nihilism. From Severino’s point of view, one might as well define Cioran’s thought as the becoming aware of nihilism inherent to the Western conception of Time. And in Cioran’s mystical temptation, on the other hand, one may find a sentimental perception of Being which seems to point to the need, the urge, the hope, so to speak, for an overcoming of Western hermeneutics of Becoming and for an ulterior word that is not Negation. The book starts with an account of my three encounters with Aurel, Cioran’s brother, in the years of 1987, 1991 and 1995, and of my two encounters with Emil, in 1988 and 1989. The book also includes all the letters which Cioran wrote to me, plus countless photographs. After the first part, there comes a bio-bibliographical inquiry on his Romanian years, a pioneer work of exhumation at a time when there were no reliable sources on the matter.

Par son renoncement hypnotique à l'égard de tout ce qui séduit l'intellect ou la

Par son renoncement hypnotique à l'égard de tout ce qui séduit l'intellect ou la