Earlier this year, Fox News host Tucker Carlson sparked a spirited intra-conservative debate about the Right’s fidelity to free market capitalism, the perils of a consumer culture, and the opportunities and limits of public policy.

Over the course of a 15-minute, widely circulated monologue, the primetime firebrand harnessed the spirit of our political moment. Sounding equal parts Donald Trump and Elizabeth Warren, he lamented the plight of the working and middle classes, questioned whether cheaper consumer goods are an accurate barometer of prosperity, claimed that anybody who equivocates the health of a nation with its GDP is “an idiot,” and scorned what he considers to be a self-serving ruling class with no loyalty to the people it governs.

“We do not exist to serve markets,” Carlson declared indignantly. “Just the opposite. Any economic system that weakens and destroys families is not worth having. A system like that is the enemy of a healthy society.”

Although Carlson’s monologue took some liberal observers by surprise, it fits quite comfortably in an oft-neglected strand of conservative thought—ranging from traditionalist Russell Kirk, first-generation neoconservatives Irving Kristol and Daniel Bell, and paleoconservative Pat Buchanan—that has long chafed at the civic and social consequences of a consumer-driven political economy.

Carlson’s monologue also serves as the latest evidence of the ever-growing discontent that has animated both the Left and the Right since the 2008 global financial crisis. Unable or unwilling to adapt to the frustrations of left-behind Americans, the nation’s institutions face a crisis of legitimacy. The political fortunes of center-left and center-right politicians have diminished, and so-called populists are at the barricades.

Yet while tapping into popular dissatisfaction has proven useful in galvanizing the electorate, it does not guarantee that an effective program will replace the status quo. Polemics, though oftentimes necessary precursors for political change, are no substitute for a coherent governing agenda. If our political moment is to yield a productive populist program, it will require more than fire and brimstone alone.

♦♦♦

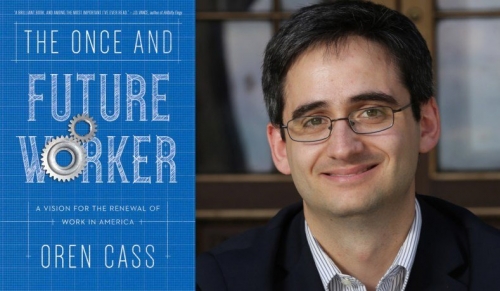

For those who believe that the country’s current trajectory is untenable, but balk at the alternative of ascendant democratic socialism, critical rethinking of our approach to public policy is necessary. Oren Cass’s The Once and Future Worker, published in November by Encounter Books, is already proving an essential text for such a project.

A senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and an economic advisor to the 2012 presidential campaign of Mitt Romney—a politician on the receiving end of much of Carlson’s contempt—Cass is no radical. He is, however, a heretic, willing to question the public policy orthodoxy that has dominated both parties for the past four decades.

In Cass’s telling, this orthodoxy consists of a tunnel-vision focus on two economic outcomes: increasing consumption (as measured by consumer purchasing power) and expanding growth (as measured by gross domestic product). And by these two metrics, such a strategy has been an undeniable success: GDP tripled between 1975 and 2015, and the average American enjoys unprecedented access to cheaper and cheaper consumer goods.

Yet this approach, which Cass cleverly dubs “economic piety,” has not been without consequences. An unquestioned allegiance to growth and consumption has blinded policymakers to all other considerations, most importantly the health of the nation’s labor market.

Contra free marketers, Cass dispels with the notion that the best labor market is the least-intervened-in labor market. Rather than a naturally occurring state of nature, the labor market must be understood as a garden—it should be tended to, and not trampled upon.

Work, in Cass’s narrative, is important, and the reader quickly concludes that he considers man’s productive capacities to be an anthropological good. The deskilling of the American workforce and the decline in male workforce participation have therefore contributed to a host of downstream consequences for families, communities, and the nation at large. These include, but are not limited to, the multifaceted drug epidemic, lower marriage and birth rates, and a corrosive politics of resentment.

As an alternative to “economic piety,” Cass proposes a framework of “productive pluralism.” Undergirding this vision is what he calls “the working hypothesis,” the principle that a “labor market in which workers can support strong families and communities is the central determinant of long-term prosperity and should be the central focus of public policy.”

To achieve this end, Cass proposes policies that range from orthodox to heterodox to innovative. For a book with an implicit theme of “tradeoffs,” The Once and Future Worker unsurprisingly contains much to like and much to hate, irrespective of the reader’s political priors and preferred policy prescriptions.

In an era of Green New Deal fervor, Cass recycles long-standing conservative appeals to cut the environmental regulations that have disproportionately handicapped the productive sectors. Striking a Trumpian chord, he advocates for restricting the flow of low-skilled immigration, not for “racist” reasons, but because an influx of low-skilled labor has been a contributing factor to the wage stagnation of America’s working class.

Although Cass believes that the Trump administration’s trade regime has been ham-fisted, he does take aim at the United States’ incoherent—if not non-existent—industrial strategy, and highlights how China’s mercantilist practices and intellectual property theft have depleted America’s manufacturing capacity since it was extended permanent trade relations in 2000.

Most provocatively, Cass challenges the accepted belief that the path to prosperity ought be paved with four-year college diplomas. He notes that the current one-size-fits-all approach to higher education has saddled students and graduates with a collective $1.5 trillion of debt and has actively undermined their ability to live stable and productive lives. He suggests that we return to a system of educational and vocational tracking—to determine which students are best suited for higher education and which are best suited for the trades—and foster a labor market in which Americans with only high school degrees can prosper as well.

Perhaps most innovatively, Cass proposes the introduction of a wage subsidy to boost the take-home pay of low-income earners. To these one might add Senator Marco Rubio’s proposal to tax capital gains at a higher rate than labor, and an ambitious plan to expand the earned income tax credit put forth by Ohio senator and presumptive 2020 presidential candidate Sherrod Brown.

Readers inclined to a more hands-off approach to public policy will no doubt view Cass as well-intentioned but mistaken. Others will view him as little more than a technocratic tinkerer. The current state of affairs, in their estimation, requires a far more radical transformation of the structure of our political economy than Cass charts out. This may well be true. But Cass’s effort to reframe our approach to public policy with a more holistic conception of the American citizen—one that seeks to put the fundamental dignity of working and family life first—is a necessary first step.

As the fallout from four decades of labor market neglect continues to realign America’s political landscape, The Once and Future Worker must serve as a foundational text for those interested in harnessing the nation’s collective angst into a populist program with a brain.

Daniel Kishi is associate editor of The American Conservative. Follow him on Twitter @DanielMKishi.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.