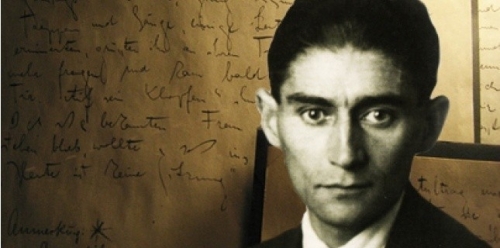

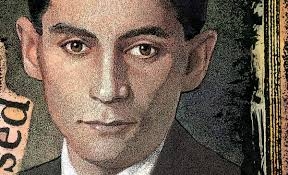

During the late afternoon of June 11, 1924, in a modest ceremony at Prague’s New Jewish Cemetery, one of the 20th century’s most influential writers was laid to rest. Franz Kafka died of tuberculosis one week earlier, in a sanatorium outside Vienna. He was just shy of his 41st birthday.

In his own lifetime Kafka’s prose bequeathed him no recognition, no fame, no notoriety, and no literary prizes. Which seems odd, considering that, apart from Shakespeare and Goethe, Kafka is one of the most written about wordsmiths in modern European literature.

But in another way, this initial lack of critical praise is hardly surprising. For starters, there wasn’t much finished work to praise in the first place. Kafka hadn’t completed a single novel before his death. The little that had been published by him was largely ignored, and few bothered to read him. With the exception of one dear friend: a fellow Prague Jew, Max Brod.

The two met as teenagers, following a talk Brod gave about Arthur Schopenhauer at a students’ Union Club on Prague’s Ferdinandstrasse. One of their first conversations concerned Nietzsche’s attack on Schopenhauer’s renouncement of the self. Pretty quickly the two curious minds became inseparable, usually meeting twice daily to discuss life, literature, philosophy, and whatever other topics might randomly arise.

Brod’s memoirs spoke about Kafka’s gentle serenity, describing their relationship almost as if they were lovers. He also recalled the mystical experience of both men reading Plato’s Protagoras in Greek, and Flaubert’s Sentimental Education in French, like a collision of souls.

Brod’s memoirs spoke about Kafka’s gentle serenity, describing their relationship almost as if they were lovers. He also recalled the mystical experience of both men reading Plato’s Protagoras in Greek, and Flaubert’s Sentimental Education in French, like a collision of souls.

While there is no evidence of any homosexual feeling between Kafka and Brod, their intimate relationship appeared to go beyond typical camaraderie from two straight men of their era.

In their early 20s the pair vacationed together on Lake Garda on the Austrian-Italian border; they paid their respects at Goethe’s house in Weimar; stayed together at the Hotel Belvedere au Lac in Lugano, Switzerland; and even visited brothels together in Prague, Milan, Leipzig, and Paris. Brod, a self-confessed ladies’ man with an insatiable appetite for adventurous sexual conquests, often berated Kafka for not having a similarly urgent drive of eros. “You avoid women and try to live without them,” Brod once told his friend.

Kafka was engaged to two women over his short life: Julie Wohryzek and Felice Bauer. But for a host of complicated reasons he married neither. Kafka reacted to women he became intimate with as he did to almost everything else in his emotional life: with anxiety, dread, concealment, fear, and despair.

♦♦♦

He coped with the failure of his intimate relationships by purposely avoiding face-to-face emotional conflict. Instead, he turned to words: specifically, to the art of letter writing. This happened not just with Kafka’s lovers, but with members of his own immediate family too. Kafka penned “Letter to My Father” in November 1919: a long, emotional epistle in which he accused his father, Hermen, of playing the role of prosecutor in what Kafka called a “terrible trial” pending between both men. Kafka then asked his mother, Julie, to pass the note onto his father. But she prudently sent it back to her son. Along with a whole host of other unfinished manuscripts, it ended up in a drawer in Kafka’s room. Brod ensured it was eventually published—posthumously—in 1952.

Brod’s graveside eulogy to his fellow man of letters and dear friend came straight from the heart. He referred to Kafka as a “prophet in whom the splendor of ‘the Shekhina [divine presence] shone.’” It was a fitting gesture, constructing the saintly prism of reverence that much of Kafka’s work would eventually be viewed through, when a global audience finally came to recognize the magnitude of his literary talents. Brod, after all, would spend the next few decades championing his friend’s genius with relentless determination and resilience.

There were even some suggestions in the immediate years following Kafka’s death that Brod was simply dining out on his friend’s genius and using him for his own career advancement. These accusations came from serious literary critics and huge admirers of Kafka’s work, such as Gershom Scholem and Walter Benjamin. But they appear to be grounded in petty jealousy rather than substantial evidence. Today, readers of Kafka ought to be cautious of such cynicism. Without Brod’s determined efforts, Kafka’s work would have never seen the light of day.

The American historian Anthony Grafton has referred to early-20th century Prague—where Kafka wrote some of his greatest work—as “Europe’s capital of cosmopolitan dreams.” Like Vienna in the same period, it was a vibrant bohemian metropolis where literature, painting, philosophy, and poetry flourished, under the unified German-speaking Habsburg Empire, which collapsed suddenly in 1918. By the age of 25, Brod was at the heart of this diverse cultural community, keeping in regular contact with the great and the good of central Europe’s literati; this included Hermann Hesse, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Thomas Mann, and Rainer Maria Rilke. In many of these correspondences, Kafka was never far from Brod’s thoughts.

In 1916 Brod even wrote to the Austrian philosopher Martin Buber, explaining how frustrating it was to watch his best friend’s lack of enthusiasm for his own creative process: “If you only knew his substantial, though unfortunately incomplete novels, which he sometimes reads to me at odd hours,” Brod wrote. “What I wouldn’t do to make him more active!”

In 1916 Brod even wrote to the Austrian philosopher Martin Buber, explaining how frustrating it was to watch his best friend’s lack of enthusiasm for his own creative process: “If you only knew his substantial, though unfortunately incomplete novels, which he sometimes reads to me at odd hours,” Brod wrote. “What I wouldn’t do to make him more active!”

It wasn’t that Kafka didn’t take his writing seriously. As early as 1913, for example, he wrote in one diary entry that “I am made of literature. I am nothing else and cannot be anything else.”

Conversely, Kafka’s writing resembled something closer to a secular prayer: where he attempted to transcend his tortured, neurotic, and anxious mindset into something resembling universal existential truth—a task the troubled writer never saw as a simple procedure. Reading Kafka’s diary entries gives us a clearer view of what he thought about his own writing.

Take Kafka’s short novella, The Metamorphosis. It describes how a young man, Gregor Samsa, wakes up suddenly one day to discover he has turned into an insect. Becoming a burden on his family, Gregor becomes distressed by his father’s abusive physical actions towards him, and eventually he dies. The whole event brings a great sense of relief to the family, who decide to move to a smaller apartment, which they could not have done if Gregor was still alive.

Kafka described the novella in one diary entry as “imperfect almost to its very marrow.” In another entry, Kafka vented his frustrations about why he believed his own inner mental world could only be lived and not described. “I am constantly trying to communicate something incommunicable,” he wrote. Ironically, it was this unknowable and unnamable force—that Kafka couldn’t quite put a precise label on with language—that became his most valuable asset as a writer.

A number of critics have described Kafka as a prophet, viewing his work through a political and sociological lens in which he foresaw the evil forces of 20th-century totalitarianism. Some have even gone as far to say that he predicted the Holocaust. Reading the final page of The Trial, for example, one becomes eerily spooked by Kafka’s subtle observation that individuals—either in a solitary manner or collectively—can be condemned to death for doing nothing wrong, committing no crime, breaking no moral code.

But a wide array of interpretations on Kafka’s work would come much later. In fact, most of Kafka’s ideas and words nearly vanished with him into an early grave. Thankfully, for the sake of literature, and posterity, the Kafka canon survived. In time, its idiosyncratic signature stamp would become a recognizable adjective: Kafkaesque.

The term would come to represent a whole host of traumas that appeared to have subtly infected Western society—and subsequently the individual Western mind—since the coming of modernity, including existential angst, alienation, paranoia, isolation, insecurity, the labyrinth of state bureaucracy, the corrupt abuse of totalitarian power, and the impenetrable tangle of legal systems. With its unique exactitude and precision, Kafka’s prose describes a milieu where individuals—for reasons unbeknownst to them—feel utterly powerless, confused, trapped, and subsumed into a world they really do not understand. And, perhaps more importantly, they become dehumanized in the process.

As the British literary academic John R. Williams puts it rather aptly in The Essential Kafka, the Czech modernist writer frequently expressed himself through aphorism and parable, in stories that represent “remoteness, hopelessness [and] the impossibility of access to sources of authority or certainty or what in German is termed Ausweglosigkeit—the impossibility of escape or release from a labyrinth of false trails and frustrated hopes.”

As the British literary academic John R. Williams puts it rather aptly in The Essential Kafka, the Czech modernist writer frequently expressed himself through aphorism and parable, in stories that represent “remoteness, hopelessness [and] the impossibility of access to sources of authority or certainty or what in German is termed Ausweglosigkeit—the impossibility of escape or release from a labyrinth of false trails and frustrated hopes.”

Kafka’s work, Williams stresses:

appears to have articulated, and indeed to have prefigured, many of the horrors and terrors of twentieth-century existence, the angst of a post-Nietzschean world in which God is dead, in which there is therefore no ultimate authority, no final arbiter of truth, justice or morality.

The key moment for rescuing Kafka’s manuscripts came in the immediate hours following Kafka’s funeral: when his parents asked Brod back to their home to go through their son’s desk. It was there Brod made a discovery that would drastically transform the fate of modern literature. Looking through Kafka’s drawers, he came across two notes. The first, written in pen, left instructions that everything left behind belonging to Kafka—including notebooks, manuscripts, letters, and sketches—were to be destroyed.

The second, written in pencil, read:

Dear Max,

Here is my last will concerning everything I have written: Of all my writings the only books that can stand are these: “The Judgment,” “The Stoker,” “Metamorphosis,” “Penal Colony,” “Country Doctor,” and the short story “Hunger Artist”…But everything else of mine is extant…all these things without exception are to burned, and I beg you to do this as soon as possible.

-Franz

But why was Kafka so adamant to destroy his own work? Dora Diamant—who was in her mid-20s when she was Kafka’s lover in Berlin during the last year of his life—claimed the writer wanted to burn everything he had written in order to “free his soul from [his] ghosts.”

Brod wasn’t surprised by the note. He had always understood Kafka’s complicated relationship with what he often casually referred to as his “scribbling.” And whenever Kafka did read to him from his manuscripts, it usually involved a great deal of pleading, cajoling, and persuading.

Kafka isn’t the first author in the history of Western literature who requested that their work go up in a ball of flames. The Roman poet Virgil was so frustrated and dissatisfied with The Aeneid that on his deathbed in 19 BC he ordered for the manuscript to be burned. The English poet Philip Larkin also instructed that all his diaries be burned just three days before he died in December 1985, while the Russian writer Vladimir Nabokov similarly left instructions for his rough draft of The Original of Laura to be destroyed.

♦♦♦

With Kafka, though, no narrative ever follows a simple, straightforward pattern. Even his dying wishes contained a multitude of conflicting requests that could be left open to interpretation. Discerning Kafka’s true will was a bit like trying to deconstruct the infinite possibilities contained within the enigmatic codes of a sacred Kabbalistic scroll. Kafka even admitted in one letter to Brod that “concealment has been my life’s vocation.”

In Kafka’s Last Trial, Israeli writer and cultural commentator Benjamin Balint suggests (but also questions) that Kafka’s last instruction to Brod can perhaps be understood as a gesture of a literary artist “whose life was a judgment against itself? As a self-condemnation, with Kafka acting as both judge and the accused?”

The literary biography covers a wide range of topics, including an in-depth analysis of Kafka and Brod’s complex relationship. It also dissects Kafka’s rather indifferent notion towards identity and rootedness which, in turn, leads to a conversation about his Jewishness. All of this is good foundational reading for understanding the book’s central focal point, which involves a complicated legal battle in Israel that has dragged on since the mid-1970s relating to Kafka’s literary estate.

The literary biography covers a wide range of topics, including an in-depth analysis of Kafka and Brod’s complex relationship. It also dissects Kafka’s rather indifferent notion towards identity and rootedness which, in turn, leads to a conversation about his Jewishness. All of this is good foundational reading for understanding the book’s central focal point, which involves a complicated legal battle in Israel that has dragged on since the mid-1970s relating to Kafka’s literary estate.

The decades-long trial—no pun intended—centered around one fundamental question: who is the rightful cultural guardian of Kafka’s original manuscripts, since the passing of Max Brod in 1968? Do they belong to Eva Hoffe (the daughter of Brod’s good friend, Esther Hoffe, who was clearly cited as a beneficiary of Brod’s estate in his will), or should Brod’s dedicated commitment to the Zionist project ensure the manuscripts find a home at the National Library of Israel? But then, considering that Kafka wrote, thought, and spoke in German, should they not perhaps find their place in the German Literature Archive in Marbach, Germany?

In August 2016, that question was finally answered by Israel’s Supreme Court: it ruled that Eva Hoffe must hand the entire Max Brod estate—including Kafka’s manuscripts—over to the National Library of Israel, for which she received no compensation in return.

Balint’s impartial and measured style ensures he avoids dogmatic personal judgments or opinions. And when he does lean towards persuasion and argument, he does it with subtlety, meandering and exploring his way through a complicated literary history that spans several decades, countries, and individuals, all of whom are randomly interlinked to Kafka’s original manuscripts.

Balint points out, for instance, the rather odd notion of Germany laying claim to a writer whose family was decimated in the Holocaust, where German was the official administrative language that slaughtered millions of Jews. He also notes that Kafka—who always considered himself the ultimate outsider and a kind of citizen of nowhere—didn’t have much love for finding a place he could call home anywhere, least of all a Jewish state in Palestine.

Interestingly, Balint also reminds us that Israel has never had much love for Kafka either, despite its decades-long legal battle to publicly house his work on display for purposes of cultural appropriation and national prestige. There are no streets named after Kafka in Tel Aviv or Jerusalem, as there are in European cities. And translations of Kafka’s work into Hebrew weren’t exactly met with speedy enthusiasm either.

But this is just one of many of the ironic twists in Balint’s book, which tend to present themselves, ubiquitously, in typical Kafkaesque fashion.

♦♦♦

The most prevalent example of this came in October 2012, Balint notes, when Judge Talia Kopelman Pardo, of the Tel Aviv family district court, reopened a case against Esther Hoffe in an Israeli court case 40 years earlier. The judge took the unusual step of quoting a passage from Kafka’s The Trial: indicating a case where art really does mirror life. Specifically, she quoted a passage from the novel that relates to the timeless nature of files in the legal world, pointing out how “no file is ever lost, and the court never forgets.”

Back in 1915 after Kafka read Brod two draft chapters of what was then his novel in progress, The Trial, Brod documented in his diary that his friend was “the greatest writer of our time.” Published posthumously in 1925, The Trial is Kafka’s masterpiece; it tells the story of Josef K., a 30-year-old bank clerk. The novel’s opening sentence explains how “someone must have been spreading slander about K., for one morning he was arrested, though he had done nothing wrong.” The short passage’s paranoid uncertainty and consistent hints towards some unknown catastrophe exemplifies—with great clarity and precision—a literary style that made Kafka such a unique writer of prose fiction.

In the novel’s final scene, Josef K. becomes aware that his life is culminating towards sudden execution.

At one stage Josef K. is tempted to “seize the knife himself…and plunge it into his own body.” In the end, however, he cannot bring himself to carry out his own execution. Balint claims that, just like Josef K., Kafka lacked the strength to carry out his own last sentence: the destruction of his own writings—both personal (letters and diaries) and literary (unfinished stories). Instead, he left that execution to Brod, a friend who as early as 1921 had told Kafka with frank directness, when he had first mentioned his request to burn all his work, that “I shall not carry out your wishes.”

In an essay published in 1983 on Kafka’s three novels—Amerika, The Trial, and The Castle—the Scottish author, James Kelman, drew particular attention to the ambiguous and mysterious relationship that Josef K.’s arrest in The Trial displays to us about the very nature of “the Law.”

The Law exists, Kelman explains: “But it exists outside of society as K. understands it. He has been ignorant of it. He has been living under a misapprehension.”

Everything relating to this mysterious Law suggests it is under the control of human reason, Kelman, notes. And yet, it is a peculiar form of human reason that seems to be attempting “to translate something that must remain outside human understanding into a form which human beings can understand.”

Kelman’s rather ambiguous conclusions about Kafka’s work seem like an apt note on which to end this discussion. Kafka, after all, is a writer whose work epitomizes the unnerving anxiety and mystery that faces any human being seeking to find meaning in their daily existence, pace modernity. Scientific and industrial advancement may have replaced spiritual authority and absolute truths, and enlightenment may have even replaced theology, but at what cost? In its place—Kafka’s work seems to subtly suggest—is an unexplainable empty vacuum: an infinite black hole of uncertainty, where fear and existential dread collide.

But one’s reaction to such a cold and despairing analysis of the human condition depends, of course, on whether you generally tend to see the glass half full or half empty. As Kelman nicely puts it: “there is nothing in Kafka’s work to suggest any source of power beyond humankind itself, but whether or not this represents grounds for pessimism depends on the individual reader’s own beliefs.”

JP O’Malley is a journalist, writer and cultural critic, who writes for a host of publications around the globe on literature, history, art, politics, and society.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.