Yet, the Boer Wars were hard for the Afrikaners to overcome. Truth be told the British had been magnanimous conquerors and South Africa had prospered under British rule but bitter memories still remained. For many, such as Maritz, it did not matter how gentle the British had been after the war it did not erase their memories of the succession of British invasions, the wars of conquest or the British concentration camps where Boer women and children died horribly of disease and starvation. Men like Maritz were simply biding their time for yet another opportunity to take their revenge and drive out the British and with the coming of World War I it seemed that their chance had come. Making common cause with the Germans only seemed natural. During the Boer War the Germans were openly sympathetic to the Afrikaners and Kaiser Wilhelm II had got into some controversy with his British cousins over his words to Boer leader Paul Kruger. German colonial forces in Africa were very weak compared to the surrounding Allied powers and the colony of German Southwest Africa in particular knew they would soon come under attack by the British in South Africa. Their only hope for survival was for a Boer rebellion which would throw the British off balance and allow the Germans and the Afrikaners to unite against them.

The British themselves were rather worried about how the Boers would respond to the outbreak of war with Germany and with good reason. Of the three preeminent Boer leaders from the freedom wars; Louis Botha, Christiaan De Wet and Jacobus Hercules (Koos) De la Rey only Botha was considered reliably loyal to the British. Many Afrikaners took divergent positions based on different motives but a sizeable minority at least were not prepared to fight against a nation that had sympathized with them in their own struggle for freedom in the service of those who had conquered them. The First World War was their opportunity to take revenge and the Germans counted on this, stockpiling a great deal of weapons and ammunition to equip the rebel Boer army they hoped would soon emerge. The Germans had been spreading the word for some time that with their help the Boers could drive out the British and establish a greater empire for themselves in Africa more to their own liking. As war erupted in Europe both sides began to form up in South Africa.

Louis Botha, newly elected Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa, pledged his loyalty to the British Empire and agreed with London to launch the conquest of German Southwest Africa which many Boers opposed. Christiaan De Wet was advocating opposition to Britain and alliance with Germany and General Koos De la Rey, who was believed to be on the side of rebellion, was gunned down by British police before his influence could have effect. Likewise, Christiaan Frederik Beyers, commandant-general of the Union of South Africa Defense Force, resigned his position to join the rebel faction as did General Jap Christoffel Greyling Kemp who was in charge of the training post at Potchefstroom. However, the most dangerous of them all was Colonel Salomon Gerhardus (Manie) Maritz who was to have been on the front lines of the invasion of German territory. Maritz was sent orders to report to Pretoria in the hopes of neutralizing him but he smelled the trap and ignored the order. War might have been headed for German Southwest Africa but it was to hit South Africa first.

British intelligence reported that Maritz and his officers were openly speaking of joining the Germans. True enough, Maritz announced his intention to ally with the Germans to his commandos and his allegiance to the provisional rebel government of the former Boer republics. He proclaimed the independence of South Africa, the Orange Free State, Cape Province and Natal and called upon the White population to join him and their German comrades in revolt against the British. It was October, 1914, and Maritz gave his men one minute to decide whether they were on the side of the Boer-German alliance or the British. Most followed their commander but about 60 remained loyal to Britain and were duly handed over to the Germans as prisoners of war. Rallies were held, speeches were given, and passionate appeals on behalf of Afrikaner nationalism were voiced as the rebellion seemed to be catching on. Beyers, De Wet, Maritz, Kemp and Bezuidenhout were chosen to lead the provisional Boer government and newly promoted General Manie Maritz occupied Keimos around Upington which had been his previous area of operations. Fighting broke out in local clashes between rebel and loyalist factions.

The British themselves were rather worried about how the Boers would respond to the outbreak of war with Germany and with good reason. Of the three preeminent Boer leaders from the freedom wars; Louis Botha, Christiaan De Wet and Jacobus Hercules (Koos) De la Rey only Botha was considered reliably loyal to the British. Many Afrikaners took divergent positions based on different motives but a sizeable minority at least were not prepared to fight against a nation that had sympathized with them in their own struggle for freedom in the service of those who had conquered them. The First World War was their opportunity to take revenge and the Germans counted on this, stockpiling a great deal of weapons and ammunition to equip the rebel Boer army they hoped would soon emerge. The Germans had been spreading the word for some time that with their help the Boers could drive out the British and establish a greater empire for themselves in Africa more to their own liking. As war erupted in Europe both sides began to form up in South Africa.

Louis Botha, newly elected Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa, pledged his loyalty to the British Empire and agreed with London to launch the conquest of German Southwest Africa which many Boers opposed. Christiaan De Wet was advocating opposition to Britain and alliance with Germany and General Koos De la Rey, who was believed to be on the side of rebellion, was gunned down by British police before his influence could have effect. Likewise, Christiaan Frederik Beyers, commandant-general of the Union of South Africa Defense Force, resigned his position to join the rebel faction as did General Jap Christoffel Greyling Kemp who was in charge of the training post at Potchefstroom. However, the most dangerous of them all was Colonel Salomon Gerhardus (Manie) Maritz who was to have been on the front lines of the invasion of German territory. Maritz was sent orders to report to Pretoria in the hopes of neutralizing him but he smelled the trap and ignored the order. War might have been headed for German Southwest Africa but it was to hit South Africa first.

British intelligence reported that Maritz and his officers were openly speaking of joining the Germans. True enough, Maritz announced his intention to ally with the Germans to his commandos and his allegiance to the provisional rebel government of the former Boer republics. He proclaimed the independence of South Africa, the Orange Free State, Cape Province and Natal and called upon the White population to join him and their German comrades in revolt against the British. It was October, 1914, and Maritz gave his men one minute to decide whether they were on the side of the Boer-German alliance or the British. Most followed their commander but about 60 remained loyal to Britain and were duly handed over to the Germans as prisoners of war. Rallies were held, speeches were given, and passionate appeals on behalf of Afrikaner nationalism were voiced as the rebellion seemed to be catching on. Beyers, De Wet, Maritz, Kemp and Bezuidenhout were chosen to lead the provisional Boer government and newly promoted General Manie Maritz occupied Keimos around Upington which had been his previous area of operations. Fighting broke out in local clashes between rebel and loyalist factions.

On October 26, 1914 the British side made the state of war clear when Louis Botha personally took command of the forces assembling to crush the Boer rebellion. It was the first and so far only time that a British Empire/Commonwealth prime minister led troops into battle while in office. Moreover, this was especially difficult for old Boer soldiers like Botha and Jan Smuts who would be fighting against their own people, many of them their own comrades from the previous wars against the British. However, Botha and Smuts were truly committed to the Allied cause and when Australian troops on their way to Europe were offered to help crush the rebellion Botha refused and preferred to use loyalist Afrikaners to suppress the rebel Afrikaners so as not to exacerbate the Boer-British ethnic tensions which were obviously already running high. Volunteers, reserves, support personnel and the like were all mobilized in this massive effort by the Union government to stamp out the uprising before the Boer rebels spread their influence and forged a coordinating strategy with the Germans which would have been disastrous.

The Boer rebels were busy as well. General De Wet took his Lydenburg commandos and seized Heilbron and captured a British train which provided a wealth of supplies and ammunition. Soon De Wet had 3,000 men under arms while General Beyers mobilized more in the Magaliesberg in addition to those already assembled around Upington under General Maritz. On the loyalist side, Botha took command of 6,000 cavalry and some field guns assembled at Vereeniging in the Transvaal with the aim of destroying De Wet. Martial law was declared and overwhelming government force was brought down on the rebels. General Maritz was defeated on October 24 but escaped into German Southwest Africa where he continued his own resistance. Botha caught General De Wet at a farmhouse in Mushroom Valley and broke the Boer rebels on November 12. General De Wet and a remnant of his men retreated into the unassuming but brutal Kalahari Desert. General Beyers and his commandos met with an initial defeat at Commissioners Drift after which he joined forces with General Kemp. However, they too were beaten and Beyers drowned while trying to escape across the Vaal River. Kemp led the rest of his men to safety in German territory to join up with General Maritz but only after a long and brutal march across the Kalahari. Kemp was eventually captured in 1915 though by his former comrade General Jaap van Deventer after which he served time in prison and went on to become minister of agriculture in 1924.

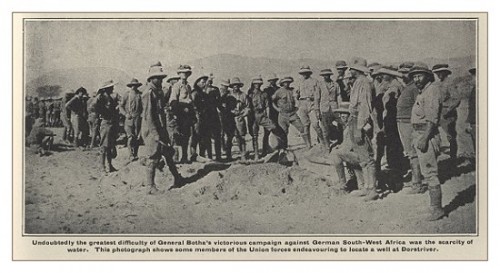

The potential Boer rebellion had been crushed in its infancy and Prime Minister Botha went ahead with his invasion of German Southwest Africa. On hand to oppose him was Manie Maritz who had no intention of giving up so easily. He was aided by the fact that the Germans had probably the best colonial army in Africa and although hopelessly outnumbered they fought with considerable skill and tenacity. Early German victories hurled the British invasion back and forced Botha to take a more careful approach. He heard of General Maritz again when the rebel Afrikaner took his Boer troops and with German assistance attacked his former base at Upington, inflicting quite a bloody nose before General van Deventer beat them back. The Union troops faced stiff German resistance, harassing artillery fire, poisoned water wells and land mines in their march into the interior of Southwest Africa. The Germans won a number of stunning victories but eventually the strength of British numbers, some 60,000 troops, proved impossible to overcome and German Southwest Africa was conquered. The British also liberated the loyalists Maritz had turned over to the Germans when they took Tsumeb where the Germans had also been keeping their weapons stockpile for the Boer rebellion.

However, the rebellious General Manie Maritz was not to be captured having escaped yet again, this time to the safety of then neutral Portuguese West Africa (Angola). For the rest of the war years he traveled to Portugal itself and later Spain before returning to his native South Africa in 1923. Once back he proved just as troublesome for the British as he ever had and still somewhat attached to Germany as time would tell. In 1936 he organized a South African Nazi type party with typical anti-Semitic rhetoric thrown into the mix. Of course, in reality, Jews were hardly a presence in South Africa, but it was part of an overall Afrikaner nationalist program and to the disgust of the British and pro-Union South Africans he continued his agitation even after the start of World War II. He did not live to see the final defeat of Nazi Germany though as he died in a car wreck on December 19, 1940 in Pretoria. A lifelong Afrikaner nationalist and enemy of Great Britain he certainly regretted nothing. It would be easy to say (and many have) that the entire Maritz rebellion and the German defeat in Namibia were an exercise in futility and a complete waste of time. However, although the Boers remained subject to Britain and the Germans lost what was arguably their most profitable colony, in a way the German and Boer campaigns were a success for the Central Powers in that they delayed considerably the mobilization of South African troops for use against the more formidable German colonial army in German East Africa (which went on a rampage) and they prevented any transfer of South African troops to the western front during the vital battles fought in 1914. That being said, the evaluation of these actions still depends a great deal on the point of view of the observer. To the British and loyalists General Maritz was a traitor of the blackest sort, a collaborator and ranked at the top of the list of enemies of the British Empire. However, General Maritz is still revered by some Afrikaner nationalists for his dogged defiance and by modern day neo-Nazi Boers who think he was on the right side in World War II as well.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.