lundi, 18 mars 2013

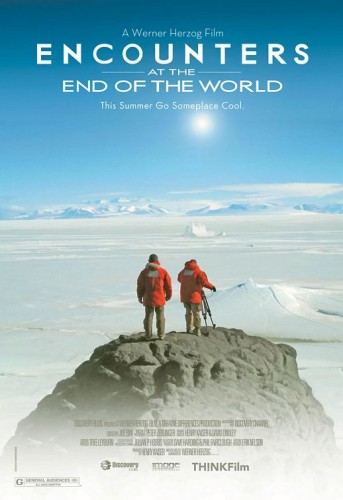

Werner Herzog’s Encounters at the End of the World

Werner Herzog’s Encounters at the End of the World

By James Holbeyfield

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Bavarian director Werner Herzog’s Antarctic odyssey Encounters at the End of the World [2] was released in 2008. It is not a work of fiction, with all the inspirational, mythological, and crystallizing power of high art; it is a documentary. It is not even, overtly at least, on the grandiose IMAXimal scale at the top of the funding ladder for conventional documentaries. But it is a film by Werner Herzog, and when a white man of Herzog’s artistic caliber has spoken, we do well to listen.

And on the very subject of Herzog’s speech, from the film’s start I was struck by the utter appropriateness of his physical voice, and I then realized that this had been true of his other films I have seen since he entered his “follow your fancy” phase of documentaries; movies that surely have the most favorable ratio of directorial talent to production budget of any in recent history.

Of course as an American, one is easy prey to certain variants of European-accented English; perceptions of discriminating taste in the received pronunciation of Oxbridge or perceptions of scientific precision in a German accent. But it was a real revelation to consider that, after three generations of blond, ice-cold, German-accented pure evil emanating from Hollywood, Herzog’s distinctly German harmonics and cadence seem to me a very appealing combination of soothing avuncularity and quiet passion.

Next, I was struck by the challenge to character that Antarctica must offer. The film opens with what seems the ultimate in gen-Y rootlessness: the gaping cargo hold of a US Air Force C-17 on wing from New Zealand to McMurdo. Travelers are snuggled under massive, lashed-down equipment like hipsters scattered about the summer decks of the Alaska State Ferry. But that must be deceptive; presumably one does not get to McMurdo, even as a janitor or barkeep, simply by buying a ticket. There must be some screening going on, probably explicit and definitely some implicit self-screening, involving the personality and character of the people who apply.

Once landed “in town,” Herzog wastes little time in showing disdain for the place. That is understandable; he must immediately have felt that he didn’t come to the end of the world to hang around its dreary, entirely artificial, service sector, necessary though dormitories, gyms, restaurants, cinema, fuel tank farms, watering holes and even an ATM are, in modern Antarctica as in modern everywhere. Still, Herzog recognized the unfairness of that attitude, and furthermore recognized a potential opportunity that he should be the last director on earth to lose; sprinkled through the film, he more than makes up for this disdain for the artificial quality of McMurdo, by inserting many neatly focused character vignettes that capture the “ultimate wanderer” nature of many McMurdo denizens.

Among them is Scott Rowland, a Colorado banker turned ice-bus driver, whose eight-ton vehicle is nicknamed “Ivan the Terra-bus.” There is William Jirsa, a linguist and computer analyst who ironically now finds himself in the one continent without native languages. And among several others, there is equipment operator and offbeat philosopher, Bulgarian Stefan Pashov, who interprets the particular role of the full-time travelers/part-time workers, the “cosmic dreamers” who are drawn to McMurdo, via a quote from Allan Watts. “Through our eyes, the universe is perceiving itself. Through our ears, the universe is listening to its harmonies. We are the witnesses through which the universe becomes conscious of its glory, of its magnificence.”

Most of the film is devoted to portraying slices, many of intoxicating visual richness, from various scientific projects in Antarctica, including studies of glaciology (“the iceberg I’m studying is not only larger than the one the Titanic hit, and larger than the Titanic itself, it’s larger than the country that built the Titanic”), seals, invertebrate ecology, a volcano, the South Pole, a neutrino detector, and yes, even a touching scene with some penguins, despite Herzog telling us, early on in the film, that he informed the National Science Foundation “I would not come up with another film on penguins.” (This last presumably referred to avoiding any accusations of trying to piggyback onto the blockbuster — for a documentary — March of the Penguins [3], first released in 2005.) And from what I have seen, most of the commentary on the film has been content to concentrate on its interesting science and visual wealth.

However, I think it is an inescapable conclusion that Herzog had an even larger theme in mind as this film came into being, one that would eventually determine its entire narrative direction. Not for nothing did Werner Herzog title this movie Encounters at the End of the World. To me, and evidently to Roger Ebert [4], to whom the film is dedicated, it is quite clear that, in addition to the obvious spatial meaning of his title, with Antarctica objectively existing at one end of our spinning planet, Herzog meant it temporally as well. In other words, Herzog recognizes that exploration and research on Earth’s last continent can be symbolic of, at the very least, the deceleration of human progress in the modern world, and perhaps of outright stagnation or even reversal. Werner Herzog definitely has some insight into Kali Yuga.

Herzog visits the remains of Shackleton’s ship, now a sort of museum. He alludes to the triumph of Amundsen and the tragedy of Scott in their epic race to the Pole. Though he does not find these Antarctic pioneers praiseworthy in every single respect, noting a degree of arrogance in the last-gasp imperialism of the contest, particularly for the Britons, Herzog is quite deliberate in distinguishing the achievements of these giants of the quite recent past to the pursuits of today’s continental Americans. To me, it is extremely telling that, to make the strongest contrast with the heroic achievements of the early Antarctic explorers directly, Herzog chose scenes, filmed in America, of a very fit and very chipper man, riding the tiger I suppose in his own way, by attaining literally hundreds of odd titles in the Guinness Book of World Records, including such novelties as Marmite eating and marathon somersaulting (his goal was to set at least one record on every continent, and that included Antarctica, thus the connection).

At this point it must be said, for white nationalist purposes at the very least, that this chipper man, born Keith Furman [5] in Brooklyn, is rather obviously a Jew; indeed so far as I can tell, the only Jew in the whole film. And I want to be clear that I do not concentrate on his Jewishness purely out of malice; in fact I can only wish I were as fit, motivated, and possessed of good habits as Mr. Furman appears to be, even if I would certainly wish any such assets on my part to lead in a quite different direction.

But I do feel two quite important points emerge from the fact of this Jewish presence. The lesser one is that it is impossible to believe that Werner Herzog, who has spent four decades in the movie industry after all, could have been completely blind as to the non-random ethnicity of this character. In investigating Antarctica, he pays high tribute to the spirit of the early explorers, explicitly Imperial European and implicitly Aryan as they were, and wishing to reach for the most striking possible contrast in post-modern heroics, a mere century after Scott and Amundsen, he settles on a Jewish holder of a world record in hula hoop racing while balancing a milk jug on the head [6]? No, no, it is quite impossible that Herzog was entirely unaware, that it was all fluke.

But regardless of the degree of intent on Herzog’s part, the larger point is that a Jew is, in fact, an excellent symbol for this particular species of last man. A Jew has to be content with somersaulting twelve miles on a rubberized track, a century after a team of Aryans has each man-hauled [7] hundreds of pounds on sledges, for ten hours a day over four months across crevassed Antarctic glaciers in weather down to forty degrees below and worse, without the benefit of modern fabrics and materials, only to die in the end so nobly that one does not wish to depress one’s comrades further and so tells them one is “just going outside [8] and may be some time”; as if to the park for a stroll. A Jew has to be content with building eyesores of the month [9] instead of the Hagia Sophia [10]. Content with filming Holes [11] instead of The Tree of Life [12]. Content with writing up a Portnoy instead of an Isabel Archer. Content with dreaming up theories of repressive mothers [13] instead of creating the evolutionary synthesis [14]. And on and on in like fashion.

One could try to argue that all this is cherry picking, sour versus sweet, except that the Jews have actually been proud of this unmitigated trash, and have convinced entire generations of the gullible that much of it represented the next big thing, the more advanced development in each field of endeavor; whereas in fact, to put the matter in Wagnerian terms, their accomplishments often are mere clumsy, ludicrous imitations of our own.

So where does this brand of nihilism lead us? Where did it lead Herzog? Not nearly as far as we would like, I’m sure. Still, I think there are a few messages. One is that we can never be certain about the future, and about the possibility of reaching for the stars. My own negativism inclines me toward Scott Locklin’s view [15] more than transhuman inevitability [16]. But Locklin and I could both be wrong. There may be more opportunities for future Amundsens and Edisons out there than we guess. Certainly I found the greatest boyish enthusiasm, ironically metaphysical, out of all the many enthusiastic white scientists portrayed in this film, to be that of the most cosmic one, physicist Peter Gorham, the neutrino researcher.

And even if it turns out such opportunities really are in decline, is that exactly the end of the world? You young white nationalists, some no doubt stewed in the internet for hours a day over almost as many years as I have been, some unwilling to travel with hipsters because they vote Democrat, and unwilling to join the Army because they die for Israel, and unwilling to roughneck the oil rigs because there they have no higher purpose; at least some of you should join these eccentrics of Werner Herzog.

So far as I could tell, again without going to foolish extremes, not one of some twenty people Herzog introduces us to by name in Antarctica is a Jew, although the jury is still out on Clive Oppenheimer, whose internet footprint does display at least a tendency to self-aggrandizement. Even brunette, accented Regina Eisert appears by googling to be German, though in the film she is wearing a snood over her hair reminiscent of those now worn by some married Orthodox Jewish women, but not so very long ago worn by white women throughout much of Europe.

The reason I’ve done this spot of googling is not so I can seethe inwardly over who is a Jew and who is not, but to demonstrate that, even at the service level, never mind the scientific level, never mind the level of a Shackleton, the cold natural beauty, the cool natural science, and the sheer adventure of Antarctica still make it the kind of place that calls to our people, and pretty much only our people. In contrast to this openness to experience, Furman’s visit to Antarctica consisted of 90 minutes pogo-sticking down a runway [17]. These people, adapted to the white brain instead of to a piece of this beautiful earth, truly know the price of every continent and the value of none.

So calling all suitable young Aryans! Some of you should apply for McMurdo, go work in Alaska, bide awhile in North Dakota or even Siberia. I have little doubt that most of Herzog’s Antarctic subjects would be Obama voters in America, but I’m saying that their actions are more implicitly Aryan than some of ours. And many of us are just as eccentric as they are, even if our eccentricity does not run to trying to save endangered languages or hitchhiking through Africa.

But if anyone does go, it would be well to shut up about whiteness for awhile. One has a better chance to be convincing later if one is first quiet and strong in such places, which are never for blowhards. Try to prove your character to yourself; it doesn’t have to be the character of Robert Falcon Scott, it just has to get better and tougher. And at the very least, you will have traveled, had some interesting experiences in unusual or difficult spots, and, if you need to earn a grubstake, it seems fair to say that barkeep pay in McMurdo must be a lot higher than in N’Awlins [18].

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2013/03/werner-herzogs-encounters-at-the-end-of-the-world/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/encounters_at_the_end_of_the_world_2007_580x435_710896.jpg

[2] Encounters at the End of the World: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B001DWNUD8/ref=as_li_ss_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=B001DWNUD8&linkCode=as2&tag=countercurren-20

[3] March of the Penguins: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B000N3SSA8/ref=as_li_ss_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=B000N3SSA8&linkCode=as2&tag=countercurren-20

[4] Roger Ebert: http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20080707/PEOPLE/657811251

[5] Keith Furman: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashrita_Furman

[6] hula hoop racing while balancing a milk jug on the head: http://www.ashrita.com/records/all_records

[7] man-hauled: http://artofmanliness.com/2012/04/22/what-the-race-to-the-south-pole-can-teach-you-about-how-to-achieve-your-goals/

[8] just going outside: http://www.englishclub.com/ref/esl/Quotes/Last_Words/I_am_just_going_outside_and_may_be_some_time._2690.htm

[9] eyesores of the month: http://www.dezeen.com/2011/11/17/dresden-museum-of-military-history-by-daniel-libeskind-more-images/

[10] Hagia Sophia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hagia_Sophia

[11] Holes: http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_OyXJF_PLAKM/TT-J-wdleuI/AAAAAAAAAFc/NOIARFtXlZI/s1600/1999+boys+of+d+tent2.jpg

[12] The Tree of Life: http://www.twowaysthroughlife.com/

[13] theories of repressive mothers: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freud#Psychosexual_development

[14] evolutionary synthesis: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julian_Huxley

[15] Scott Locklin’s view: http://takimag.com/article/the_myth_of_technological_progress/print#axzz2M4aOvuQE

[16] transhuman inevitability: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ray_Kurzweil

[17] 90 minutes pogo-sticking down a runway: http://www.ashrita.com/records/record_descriptions/pogo_stick_jumping

[18] N’Awlins: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kXpwAOHJsxg

00:05 Publié dans Cinéma | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : allemagne, cinéma, film, werner herzog |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les commentaires sont fermés.