mercredi, 10 décembre 2014

What Eastern Europe Can Teach the West

What Eastern Europe Can Teach the West

A report from Ukraine and Hungary

By John Morgan

Ex: http://neweuropeanconservative.wordpress.com

Introductory Note: Our audience should keep in mind that this article was written on May 2, 2014, and was written from a limited perspective. Therefore, it does not take into account the many negative consequences of the Ukrainian revolution which occurred in later months due to the anti-Russian chauvinism of the Western Ukrainian government. However, despite this issue, John Morgan presents many valid points on philosophical and strategic matters, and it is for that reason that we choose to republish it here. – Daniel Macek (Editor of the “New European Conservative”)

Before I begin, I want to make a disclaimer. I’ll be discussing a number of groups that I’ve had contact with, but I don’t want that to be seen as an unqualified endorsement of any of their programs or policies. I think that all of them are interesting, but I’m not here to act as a spokesman or promoter for any of them.

Before I begin, I want to make a disclaimer. I’ll be discussing a number of groups that I’ve had contact with, but I don’t want that to be seen as an unqualified endorsement of any of their programs or policies. I think that all of them are interesting, but I’m not here to act as a spokesman or promoter for any of them.

I’ll begin by describing two scenes that I witnessed in January of this year. The first was in Kiev, in the Ukraine, the night I first arrived, as I was approaching the Maidan, or Independence Square, in the center of the city. From far away, I could smell the smoke wafting from the many barrel fires used by those camped out on the Maidan for warmth and for cooking. As I got closer, I could hear the sounds from the speakers attached to the stage that had been set up by the revolutionaries. As I was to learn later, the revolutionary committee maintained a 24/7 schedule on the Maidan. Whether one ventured there at 4:00 in the afternoon or 4:00 in the morning, there was always something happening: either a speaker, a musical performance, a patriotic drama, or some such thing. This was true of the entire Maidan: It was just as bustling in the middle of the night as during the middle of the day. The protesters wanted to make sure that the government understood that their rage was not a passing phenomenon.

When I reached the square, I could see that it had been transformed into an enormous, self-sufficient city of tents and other makeshift structures. This miniature city-within-a-city extended for many blocks in both directions, to the barricades that had been hastily set up against the police the previous month and that were still being guarded by volunteers. Occupy Wall Street had nothing on these guys. Hundreds of activists had been living there for over a month, in the middle of winter, and would continue to do so for many weeks thereafter, knowing full well that the police might attack them at any moment and possibly even kill them. Some of them are still camped there as I speak. Flags and patriotic slogans festooned everything. There was no doubt in my mind, as I surveyed the scene, that change was inevitable.

The other image I want to convey is something I saw only a few days later, in Budapest, Hungary. I was invited to the Annual Congress of the nationalist party Jobbik, or the Movement for a Better Hungary, the only party in Hungary today that stands as a serious rival to the ruling Center-Right party, Fidesz. The Congress was held in an indoor sports arena on the western outskirts of the city.

When I arrived, the first startling fact was that, unlike most events of a similar nature that I’d attended in Western Europe or the U.S., there were no protesters. It came as a surprise to me that views considered “extreme” in the West are usually considered normal in the East. The second startling thing was the size of the audience. This wasn’t a hundred or so people, as is typical for nationalist-related events I attend. This was an entire arena that could seat thousands. In addition to the bleachers, the floor had been filled with chairs. Both were filled to capacity.

The day’s program consisted of speakers and musical acts, with many of the speakers and performers beginning their presentations with the cry of “Talpra, Magyar!” which was always echoed by the audience. This means, “Arise, Hungarians!” and are the opening words of the poem, “National Song,” that was written by the Hungarian poet Sandor Petofi for the 1848 revolution. The enthusiasm of the participants was palpable: They were motivated to save their people. And this is no marginal phenomenon. Three months later, in the national parliamentary elections, Jobbik went on to win over 20 percent of the vote and establish itself as the second-most powerful party in the nation.

My immediate reaction to the events both in Kiev and Budapest was the same: “Something like this could never happen in Western Europe or the United States.” But the main thing that these experiences taught me is that concern for the future of our people, which I was accustomed to seeing consigned to the margins of society, is no fringe subculture in Eastern Europe. There, nationalism—by which I mean genuine nationalism, and not what masquerades under that name in America today under the auspices of Fox News and such—is still very much a mainstream phenomenon.

What Is Happening in Ukraine

I don’t want to discuss the politics of the Ukrainian situation in great detail, since there has already been so much written and said about it. The one comment I’ll make is that, outside of Ukraine, it is always framed as a dispute over geopolitics: Russia or the EU. I can say only that, while that was certainly a catalyst, that was not the main issue for most of the people I talked to. For them, the Maidan movement was about getting rid of the Yanukovich regime, which was seen pretty much universally, as far as I could tell, as corrupt, anti-democratic, and self-serving. And certainly, the activists I talked with were more interested in ensuring the existence of an independent Ukraine as opposed to one that was merely a vassal of Washington, Brussels, or Moscow.

I was invited to speak to the Kiev revolutionary council by some friends in the nationalist party Svoboda, or “Freedom,” who were familiar with my work with Arktos. In the last election in 2012, Svoboda won more than 10 percent of the national vote, and is likely to do much better in the upcoming election, so, like Jobbik, it is more than a marginal phenomenon. Svoboda’s platform is one of anti-liberalism and anti-Communism, as well as opposition to immigration, and it calls for a return to spiritual and traditional values. (As a side note, I’ll mention that I was informed that the term “European values” is code for “traditional values” in Ukraine, which is understood to mean those values that prevailed before Communism and, later, liberal rule.)

My speech was held in the Kiev city council building, which is just off the Maidan. Members of Svoboda had stormed and occupied the building a month earlier, in early December, and it had been converted into a revolutionary headquarters. Different areas of the building had been assigned to the various political parties involved in the Maidan, and Svoboda itself occupied the main hall. Once the guards at the entrance let me in, I was greeted by the strong smell of a building in which many men were living, but which obviously hadn’t been cleaned for some time. I went there several times, both during the day and at night, and people were always busy at work on something related to the Maidan. For me, it was a unique, inspirational experience to be at the nerve center of a revolution in progress.

In the main hall, chairs had been set up auditorium style so that those volunteering on the Maidan could sit and rest during breaks. Films were projected on a screen at the front of the hall, most of them about activists who had been tortured or killed by the police. Off to one side of the hall, next to a Christmas tree, was a collection of sleeping bags, where Svoboda’s volunteers got some rest whenever they could.

Many of these people came from other parts of Ukraine, and had been away from their families and friends for weeks, just to serve the cause of the Maidan. The walls were adorned with the flags of the various parties, as well as the image of Stepan Bandera, the founder of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists that had opposed the Soviets in the mid-twentieth century, and who continues to serve as an inspiration to nationalist activists today. Once again, I was impressed by the austerities these people were willing to undergo for the sake of their people.

My own talk was on “European Values and European Patriotic Movements.” In essence, I said that the most important issue facing the Maidan wasn’t Ukraine’s geopolitical orientation, but rather how best it could orient itself to combat liberalism. To underscore my point, I outlined some of the many horrors that liberalism has wrought in North America and Western Europe in recent decades. My talk seemed to be well-received, and many people approached me afterwards with questions. It became apparent that while some Ukrainians still aspire to the mirage of the lifestyle that they imagine we have here in America and Western Europe, many of them also understand that America today represents something that should be avoided at all costs.

I’ll mention another anecdote from that evening. After my talk, a rumor started to spread through the Maidan that the police were going to storm it that very night. This turned out to be false, but we had no way of knowing that. An old man who had listened to my speech approached me and asked, “Aren’t you afraid of being beaten?” At first I laughed, but upon reflection, I realized that what he was suggesting was a real possibility. As one of my Ukrainian friends had told me, “Once they find out you have an American passport, they’ll let you go, but if they come charging in here with truncheons they’re not going to bother to ask you first.”

I realized that I had never had to think about such a thing before. I’ve been publicly associated with what could be loosely termed the “New Right” for about seven years now, but I’d never had to worry about much more than being heckled by antifa or getting an occasional nasty e-mail. But here I was faced with the prospect of actual, physical violence. Had the police attacked that night, would I have been able to stand firm, as so many others did at the Maidan, in the face of the possibility of being injured or killed? I hope and believe that the answer is yes, although I have no way of knowing for certain until the moment actually comes.

This brought home for me the fact that activism for us in the West tends to be something very abstract, a battle waged in the pages of journals or in online comments sections rather than on the streets. In the East, it still has a very palpable, existential character, with real and immediate consequences. I think this is something that we would do well to keep in mind as we go about our activities. Identity is not an idea, but something we embody and live, and as such, it should be something visible in the world around us, insofar as we have the ability to affect it. The struggle in the world of ideas is important, certainly, but ultimately this is not merely a debate, but an attempt to reshape and redefine the world—a world that is always going to fight back.

No matter how one looks at it, there are certainly aspects of what has been happening in Ukraine since the revolution that are worrisome—as in any revolution, I suppose. Nevertheless, when viewed from the perspective of European nationalism, I think the fact that, regardless of whatever one thinks of the ends they were pursuing, thousands of ordinary Ukrainians were willing to give up their time and comforts for the sake of living in tents for months, and to risk their lives for the sake of their nation—and certainly without the sense that they were being manipulated by outside forces—is something that should inspire anyone looking for real nationalist activism in the world today.

The Story of Jobbik

The story of Jobbik is much less dramatic, since it is a traditional political party pursuing power through the democratic process in Hungary, and the political situation there is quite stable at the moment. What makes Jobbik particularly interesting is the degree of its success and the ideas it propagates. Thus far I have encountered nothing like it in European politics. Jobbik was founded just over a decade ago, in 2003, and when it fought its first election in 2006, it won less than 2 percent of the vote. As I mentioned before, in this month’s election Jobbik won more than 20 percent of the vote, which, in terms of sheer numbers, ranks it as the most successful nationalist party in Europe apart from the National Front in France.

I believe Jobbik has attained this success by appealing to the growing dissatisfaction of many Hungarians with their membership in the European Union, since exiting the EU is one of the planks of the party’s platform. Increasingly, Hungarians are beginning to see the EU as nothing more than a way for the major Western European powers to amass cheap labor while Hungarians see few benefits in return. Likewise, many Hungarians, especially in the countryside, are beginning to worry about the gradual erosion of their traditional values and customs. Jobbik stands for a return to those values, and plans to increase incentives for Hungarians who are working abroad to come home, and to ensure that immigration, which is currently not a major factor in Hungarian society, stays that way. Jobbik also makes an issue out of the international capitalist system, which it claims is the primary force eroding all cultures and traditions in the world today. Jobbik favors a return to a more locally-based economic model.

Much of the rest of Jobbik’s program is highly unorthodox. Jobbik favors stronger ties with Turkey, Russia and Germany, all of which have been Hungary’s historical enemies, but which Jobbik sees as essential for constructing a bulwark against the continuing encroachment of American and Western European liberalism, under the auspices of NATO and the EU. Notable in this regard is Jobbik’s close cooperation with the Eurasia Movement in Russia of Professor Alexander Dugin, which is worth discussing in its own right.

Professor Dugin has long been an unofficial adviser to Vladimir Putin and the Kremlin, in addition to his prodigious work as an author (my own Arktos publishes his books in English) and as a professor at Moscow State University. All of his work is directed at combating the prevalence and proliferation of liberalism throughout the world, and is unique in that he is one of the few to attempt to apply the ideas of the European “New Right,” as embodied by such thinkers as Alain de Benoist, to geopolitics. The spiritual traditionalism and perennial philosophy that was originally taught by figures such as René Guénon and Julius Evola is also central to his thought. Many of Jobbik’s writings, programs and public statements show the influence of Professor Dugin and his work.

One of the most controversial aspects of Jobbik’s program is its desire for alliances with Asia and the Middle East, and the Islamic world in particular. Jobbik views the anti-Islamic stance assumed by many other nationalist parties in Europe as an error. Jobbik’s leader, Gábor Vona, said in a widely publicized statement last year that the Islamic world is the best hope in the world today to combat liberalism—although what is usually left out is the rest of that sentence, in which he said, “and I say that as a Catholic.” This statement alarmed many, but it has usually been misrepresented, since Mr. Vona has made it clear elsewhere that he doesn’t favor immigration from Islamic countries into Europe, doesn’t favor the Islamicization of Europe, and doesn’t think Turkey belongs in the EU.

Jobbik’s attitude is consistent with the metaphysical perspective of the aforementioned traditionalism of Guénon and Evola, which holds that all traditional religions share a common core and that all stand in opposition to liberalism and the excesses of the modern world. I don’t think it’s possible to understand Jobbik without some understanding of traditionalism. After Jobbik’s congress in January, I spoke with a man who was introduced to me as one of their top ideologues, who said to me, “Politics is nothing; traditionalism is everything!”

One of the party’s major magazines, Magyar Hüperión, contains translated essays by the central thinkers of traditionalism (including Guénon, Evola and Frithjof Schuon), along with articles on politics from a traditionalist perspective. Traditionalism is one of the major elements of Jobbik’s worldview, so one can understand Mr. Vona’s statements only in those terms. When he calls Islam one of the major forces that can combat liberal values—as can all traditional faiths—he does so in reference to Islam as a religion, rather than as a call for an alliance with the more radical and distasteful elements of political Islamism and jihad.

Why Not Here?

Why can’t nationalist movements be successful here? I think the answer is simply that the cultural foundations for such movements are still present in Eastern Europe while they have long since been eroded here. Whatever one may think about the Soviet Union, for half a century the Iron Curtain prevented Cultural Marxism and the worst excesses of liberalism from penetrating into the East. Thus, those societies remained ethnically cohesive and retained a strong sense of national identity, and even their religious institutions, while officially suppressed, only grew in strength by being cast into a dissenting role. Those are the factors upon which any sense of a national or ethnic culture must be founded. This is not to say that liberal trends that threaten to cancel out this advantage are not taking root in Eastern Europe. They are–particularly in the urban areas. But the rot hasn’t yet proceeded to the point where change has become impossible.

So the question is: What can Eastern Europe teach the West? Since the vital foundations of identity, culture and religion have already largely evaporated in any real sense, what is left for us? The situation is dire.

Nevertheless, I think Eastern Europe, and also what I have seen taking place in my own publishing house Arktos, can be instructive. My conclusion is that if any progress is to be made, we need to approach the problem culturally, and in terms of ideas, rather than politically. Any political movement is doomed to failure unless it can reflect the desires of a large number of its community. At the moment, what we are offering is not what most of our people desire. For that to change, we have to influence the culture. This is what the European “New Right” has been saying for nearly half a century now. Little attempt has been made to put this into practice, but I think this is the way forward. More importantly, I think we need to inspire the passions and imaginations of our people, which we have also been failing to do.

The Identitarian movement, which has been extremely popular among the youth in Europe in recent years is, in my view, the first spark of such a development. The Identitarians have shed the old language and hang-ups of conservatism without sacrificing its values, and are winning popularity by adopting many of the tactics of the radical Left: street-level activism, snazzy videos, and the like. In short, it’s cool. Also, the Identitarians have recognized what the core issue really is: identity, going beyond mere politics and ideology to something visceral. People can feel what it is to be a Hungarian or a Frenchman—it is something obvious. It’s not something that needs to be expressed in words or concepts.

Identitarianism is good for Europe, and I have hope for it; the problem is how to transfer it to the United States. What sense of identity do the majority of those of European descent have in America today? Perhaps here in the South, something still remains of the venerable Southern tradition that could still be revived. But the situation in the rest of the country seems hopelessly tragic.

Identity has become a matter of consumerism: your identity is the slogan on your shirt or which television series you like. Appeals to the benefits of the American identity of the 1950s or earlier, for most Americans today, is something as foreign and unappealing as asking them to assume the identity of ancient Egyptians. Some have suggested “white nationalism” as a solution to this problem. For me, this is insufficient, first because it’s a slippery concept in itself, and also because I find it hard to become enthusiastic about the idea that I’m “white.” A Hungarian or a Pole or a Swede has an entire history and tradition to look back on. “Whiteness,” to my mind, is too vague.

If Americans don’t have an identity to draw on, what remains? We still have the remaining factors of culture and religion to consider. Again, Eastern Europe is still rich in these things, and they are what form the basis of nationalist politics there. In America today, all we have is consumer culture and liberal platitudes. The heady days of America’s early years, which produced such wonders as Transcendentalism and the American Renaissance in literature, are long gone. And most of what passes for “religion” these days is either thoroughly compromised by liberalism or else thoroughly moronic—often both.

But what I have observed through my dealings with Arktos’ readers is that there is a great hunger, especially among young people, for new perspectives on culture, politics, and religion that are suffused with the authentic values of the traditional West, to give them something to aspire to. What they want, I believe, are new ideas and myths to inspire them and to give them a sense of purpose.

This does not mean merely conservatism in a new guise; what is wanted is more radical thinking, in the sense of going beyond the limits of what is normally considered Right-wing. In some cases, it may even involve synthesizing ideas and approaches more traditionally identified with the Left. Likewise, conservatism in the West has decayed to the point that even much of what would normally have been traditional or “Right-wing” in Western thought in previous eras now seems new and revolutionary if presented in the proper way.

It should be clear by now that the ideals that first took root in the 1960s and that have dominated our society ever since are becoming more and more shopworn. The reality that young people see around them today is full of evidence of the failures of the attempts to enact these ideals. More to the point, they are growing tired of hearing these same old catchwords trotted out again and again. I firmly believe that the cultural vigor of the West as a whole is passing, if it hasn’t already passed, from the Left to the Right. By this I don’t mean the Republican Right, which is just as liberal as its opposition, but rather what Evola termed the “true Right”—the Right founded on the timeless principles and traditions of our people.

If we continue to offer fresh perspectives in an intriguing manner, and if people continue to respond to them, I think the rest will follow. It is not enough to offer a critical, purely negative view of our civilization as presently constituted. We must offer a positive, constructive alternative vision of what we want that can be attractive to people, and that indicates to ourselves where we want to be heading.

In our own modest way in Arktos, we are trying to offer the appetizers to inspire a greater hunger in our people for a more authentic mode of living and being. Books about the realities of race and of social trends are important, and we must continue to promote them. However, I think it is even more important to offer new ideas in politics, culture, philosophy and religion, and also to produce more creative works that reflect our worldview: fiction, poetry, art, music, videos, and hopefully one day even fully-fledged films. Nothing can inspire people more than a creative vision with which they can readily identify. I hope many more groups will follow in Arktos’ footsteps in this regard.

I’ve mentioned religion, and I think I should delve into this briefly. This isn’t universal, but I have noticed a distinct attraction among many young people towards more traditional forms of spirituality and the sorts of books that Arktos publishes in this area. Traditionalism is certainly part of that. I think this is only natural, since religion at its best offers one of the last refuges of authenticity amidst a society that has become mostly plastic and virtual. And certainly many of the most highly motivated movements and activists I have known on the Right have drawn their sense of purpose, at least in part, from a sense of the spiritual.

This is particularly true of Jobbik. I think the sacred must be an integral part of any attempt to forge a new nationalist culture. This is not to say that we should attempt to propagate a specific religion, as I think such an effort could create divisions, but the cultivation of authentic forms of spirituality, provided that they are consistent with our own norms and values, is a worthy undertaking. A spiritual sense of purpose is the most highly effective way to inoculate oneself against the diseases and temptations of the liberal world.

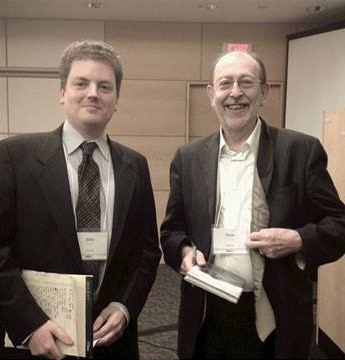

Photo: John Morgan with Alain de Benoist

Photo: John Morgan with Alain de Benoist

Hopefully, all this will lead to something corporate America learned was the key to power decades ago: the creation of a subculture, and the identity that follows from that. And, given the right circumstances, a subculture can very quickly influence the prevailing culture. If this happens, it might not even be necessary to have a political movement as such—the perspectives we offer will become commonplace and second-nature—in effect, an identity, and society will be inevitably transformed as a result. I realize this may sound overly idealistic, but the power of ideas and cultural forms should never be underestimated.

In conclusion, then, I’ll say that what Eastern Europe has shown me is that the political struggle is only the outward form of a battle that is really more cultural, and culture rests on what lies within each individual who participates in it. In order to be willing to sacrifice the comforts of home and camp out in the freezing cold, or to risk being hit by a policeman’s baton, a solid sense of identity is required.

Unfortunately, what Eastern European nationalists are born and instilled with is something that we must strive to create for ourselves, if we want to form the basis of something capable of transforming the societies we live in. And once we have achieved that for ourselves, we will provide an example that others will strive to imitate. As that great politician Gandhi once said, “If we could change ourselves, the tendencies in the world would also change. As a man changes his own nature, so does the attitude of the world change towards him. We need not wait to see what others do.” I think we can do this.

————–

Morgan, John. “What Eastern Europe Can Teach the West.” American Renaissance, 2 May 2014. <http://www.amren.com/features/2014/05/what-eastern-europe-can-teach-the-west/ >.

00:05 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : europe, affaires européennes, hongrie, ukraine, politique, politique internationale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les commentaires sont fermés.