Rolf Peter Sieferle (1949–2016) was a German historical scholar whose posthumously published book Finis Germania set off a moral panic in the summer of 2017.

A member of the generation of ’68, he was a radical in his youth, writing his doctoral dissertation on the Marxian concept of revolution. He became a trailblazer in the field of environmental history, best known during his lifetime as the author of The Subterranean Forest (1982). This book examines the industrial revolution from the point of view of energy resources, whereby it appears as a shift from sun-powered agriculture supplemented with firewood to an increasingly intense reliance on coal. The industrial revolution occurred in Great Britain partly because wood was becoming scarce or expensive to transport, whereas coal was plentiful. Although coal is also plentiful in Germany, its industrial revolution came much later because it also possessed large forests near major riverways that permitted inexpensive transportation. The Subterranean Forest is now recognized as a standard work in its field and was published in English translation in 2001.

Sieferle wrote or cowrote a dozen other books during his lifetime and was regarded as an entirely respectable member of the German academic establishment. But he moved quietly to the Right as he got older. In 1995, e.g., he published a book of biographical sketches of figures from Germany’s Conservative Revolution, including Oswald Spengler, Ernst Jünger, and Werner Sombart. This book and others published during his later years attracted some grumbling from Left-wing reviewers, but Sieferle remained respectable enough to serve as an advisor to the Merkel Government on the subject of climate change.

He retired from academic life in 2012. Following the “refugee” invasion of 2015, he quickly produced a political polemic for which he was unable to find a publisher. In September, 2016, Sieferle died by his own hand. It is uncertain to what extent his decision was motivated by failing health or distress over the migrant crisis.

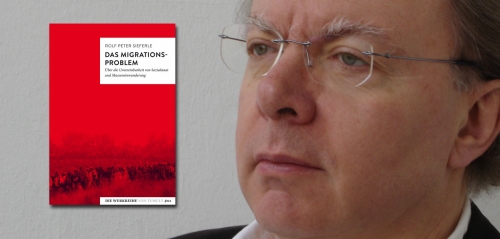

In February of 2017, his polemic was finally brought out as The Migration Problem: On the Impossibility of Combining Mass Immigration with the Welfare State. It is selling well, but the effect it produced has fallen well short of another small work discovered on Sieferle’s computer following his death: Finis Germania, or “The End of Germany.”[1] [2] This title was brought out by the dissident publisher Antaios, a fact considered scandalous in itself for a former member of the academic establishment. Antaios is the most notorious “Right-wing” publisher in today’s Germany, responsible for bringing out German editions of such unsavory authors as Jack Donovan and the present writer.

But the country was thrown into a moral panic when Finis Germania unexpectedly appeared on a prominent monthly list of ten recommended non-fiction titles. The way such lists are compiled is as follows: twenty-five editors are assigned twenty-five points each which they may award to any new titles they choose. The voting is anonymous, and the final list is compiled from the total number of points each book receives. In June, 2017, Finis Germania was listed at number nine. Denunciations rained down, with the 93-page booklet being characterized as “radically right-wing,” “antidemocratic,” “reactionary,” “anti-Semitic,” and a “brazen obscenity.” It was even debated whether Sieferle might secretly have been a “holocaust denier.”

One of the editors resigned in protest, and the monthly lists were suspended until the rules could be rewritten to make similar occurrences impossible in the future. The book’s unexpected breakthrough turned out to result from a single editor awarding all his points to it: not against the rules, but unusual. The manhunt was on to find the guilty party.

He soon made himself known in a letter of resignation as Johannes Saltzwedel, a long-time editor for the newsweekly Der Spiegel and the author of many popular works on German history and literature. He defended his action as “a vote against a Zeitgeist which was abandoning German and European culture in favor of propagating a misty cosmopolitanism.” There are many such cultural conservatives who quietly cultivate their love of Germany’s past while refraining from stirring up a hornet’s nest by publicly violating any of the Left’s numerous taboos; such men are known as “U-Boats,” and Saltzwedel had clearly scored a kill.

Finis Germania became a succès de scandale, quickly rising to the top of the bestseller lists. In July it was still at number six on Der Spiegel’s popular list of nonfiction bestsellers before mysteriously disappearing altogether: with no explanation, a gap simply appeared between number five and number seven! But the book had suffered no corresponding drop in sales.

After being bombarded with inquires, the magazine explained that they felt a special responsibility to remove a book which would not have made it onto the list without the recommendation of their own editor, Mr. Saltzwedel. Asked why they had not openly declared what they were doing at the time, the magazine offered no further explanations. The matter became a scandal within the scandal, with many of Sieferle’s harshest critics also condemning Der Spiegel for its actions. I cannot avoid the impression that such hedging resembles the rhetoric of this country’s “Alt-Lite.”

Since this website assumes its readers are competent adults, we shall let them make up their own minds about Finis Germania by publishing selected passages [3] from the work in English translation, including those which caused the greatest consternation.

Note

[1] [4] As many have pointed out, the correct Latin would read Finis Germaniae.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.