Oswald Spengler:

The Two Faces Of Russia And Germany’s Eastern Problems

An address delivered on February 14, 1922, at the Rhenish-Westphalian Business Convention in Essen

First published in Spengler, Politische Schriften (Munich, 1932).

Ex: https://europeanheathenfront.wordpress.com

In the light of the desperate situation in which Germany finds itself today -- defenseless, ruled from the West by the friends of its enemies, and the victim of undiminished warfare with economic and diplomatic means -- the great problems of the East, political and economic, have risen to decisive importance. If from our vantage point we wish to gain an understanding of the extremely complex real situation, it will not suffice merely to familiarize ourselves with contemporary conditions in the broad expanses to the east of us, with Russian domestic policy and the economic, geographic, and military factors that make up present-day Soviet Russia. More fundamental and imperative than this is an understanding of the world-historical fact of Russia itself, its situation and evolution over the centuries amid the great old cultures -- China, India, Islam, and the West -- the nature of its people, and its national soul. Political and economic life is, after all, Life itself; even in what may appear to be prosaic aspects of day-to-day affairs it is a form, expression, and part of the larger entity that is Life.

One can attempt to observe these matters with "Russian" eyes, as our communist and democratic writers and party politicians have done, i.e., from the standpoint of Western social ideologies. But that is not "Russian" at all, no matter how many citified minds in Russia may think it is. Or one can try to judge them from a Western-European viewpoint by considering the Russian people as one might consider any other "European" people. But that is just as erroneous. In reality, the true Russian is basically very foreign to us, as foreign as the Indian and the Chinese, whose souls we can likewise never fully comprehend. Justifiably, the Russians draw a distinction between "Mother Russia" and the "fatherlands" of the Western peoples. These are, in fact, two quite different and alien worlds. The Russian understands this alienation. Unless he is of mixed blood, he never overcomes a shy aversion to or a naïve admiration of the Germans, French, and English. The Tartar and the Turk are, in their ways of life, closer and more comprehensible to him. We are easily deceived by the geographic concept of "Europe," which actually originated only after maps were first printed in 1500. The real Europe ends at the Vistula. The activity of the Teutonic knights in the Baltic area was the colonization of foreign territory, and the knights themselves never thought of it in any other way.

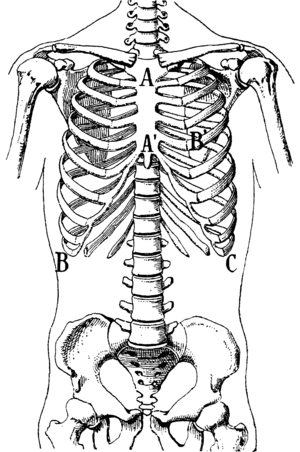

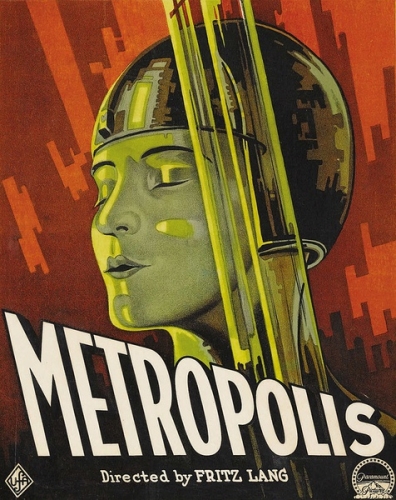

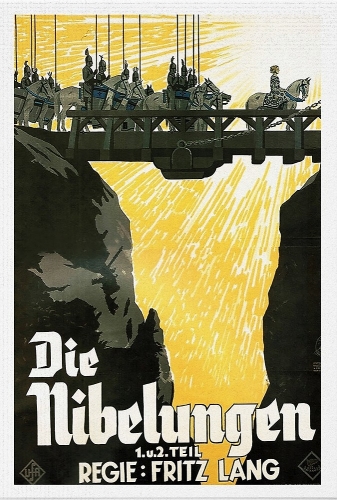

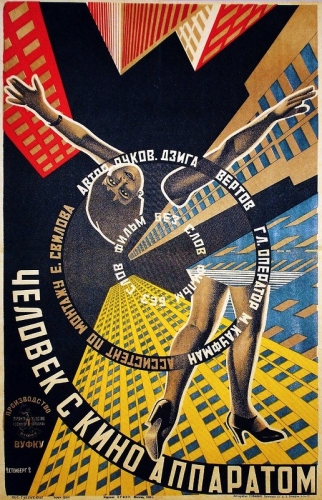

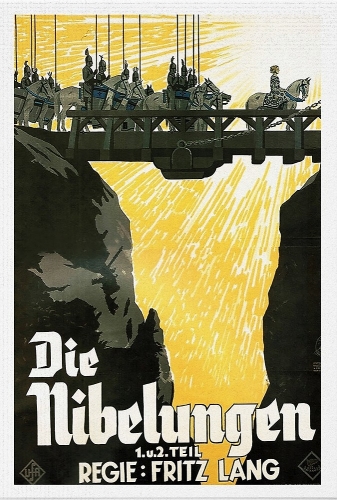

Soviet architecture, 1920s

In order to reach an understanding of this foreign people we must review our own past. Russian history between 900 and 1900 A.D. does not correspond to the history of the West in the same centuries but, rather, to the period extending from the Age of Rome to Charlemagne and the Hohenstaufen emperors. Our heroic poetry, from Arminius to the lays of Hildebrand, Roland, and the Nibelungs, was recapitulated in the Russian heroic epics, the byliny, which began with the knights at the court of Prince Vladimir (d. 1015), the Campaign of Igor, and with Ilya Muromets, and have remained a vital and fruitful art form through the reigns of Ivan the Terrible and Peter the Great, the Burning of Moscow, and to the present day. [1] Yet each of these worlds of primeval poetry expresses a very different kind of basic feeling. Russian life has a different meaning altogether. The endless plains created a softer form of humanity, humble and morose, inclined to lose itself mentally in the flat expanses of its homeland, lacking a genuine personal will, and prone to servility. These characteristics are the background for high-level politics in Russia, from Genghis Khan to Lenin.

(1. Cf. my The Decline of the West, II, 192ff.)

Furthermore, the Russians are semi-nomads, even today. Not even the Soviet regimen will succeed in preventing the factory workers from drifting from one factory to another for no better reason than their inborn wanderlust. [2] That is why the skilled technician is such a rarity in Russia. [3] Similarly, the home of the peasant is not the village or the countryside into which he was born, but the great expanses. Even the mir or so-called agrarian commune -- not an ancient idea, but the outgrowth of administrative techniques employed by the tsarist governments for the raising of taxes -- was unable to bind the peasant, unlike his Germanic counterpart, to the soil. Many thousands of them flooded into the newly developed regions in the steppes of southern Russia, Turkestan, and the Caucasus, in order to satisfy their emotional search for the limits of the infinite. The result of this inner restlessness has been the extension of the Empire up to the natural borders, the seas and the high mountain ranges. In the sixteenth century Siberia was occupied and settled as far as Lake Baikal, in the seventeenth century up to the Pacific.

(2. Cf. several stories of Leskov, and particularly of Gorki.)

(3. Except perhaps in the earlier arteli, groups of workers under self-chosen leaders, which accepted contracts for certain kinds of work in factories and on estates. There is a good description on an artel’ in Leskov’s The Memorable Angel.)

Even more deep-seated than this nomadic trait of the Russians is their dark and mystical longing for Byzantium and Jerusalem. It appears in the outer form of Orthodox Christianity and numerous religious sects, and thus has been a powerful force in the political sphere as well. But within this mystical tendency there slumbers the unborn new religion of an as yet immature people. There is nothing Western about this at all, for the Poles and Balkan Slavs are also "Asiatics."

The economic life of this people has also assumed indigenous, totally non-European forms. The Stroganov family of merchants, which began conquering Siberia on its own under Ivan Grozny [4] and placed some of its own regiments at the tsar’s disposal, had nothing at all in common with the great businessmen of the same century in the West. This huge country, with its nomadic population, might have remained in the same condition for centuries, or might perhaps have become the object of Western colonial ambitions, had it not been for the appearance of a man of immense world-political significance, Peter the Great.

(4. Grozny means "the terrifying, just, awe-inspiring" in the positive sense, not "the terrible" with Western overtones. Ivan IV was a creative personality as was Peter the Great, and one of the most important rulers of all time.)

There is probably no other example in all of history of the radical change in the destiny of an entire people such as this man brought about. His will and determination lifted Russia from its Asiatic matrix and turned it into a Western-style nation within the Western world of nations. His goal was to lead Russia, until then landlocked, to the sea -- at first, unsuccessfully, to the Sea of Asov, and then with permanent success to the Baltic. The fact that the shores of the Pacific had already been reached was, in his eyes, wholly unimportant; the Baltic coast was for him the bridge to "Europe." There he founded Petersburg, symbolically giving it a German name. In place of the old Russian market centers and princely residences like Kiev, Moscow, and Nizhni-Novgorod, he planted Western European cities in the Russian landscape. Administration, legislation, and the state itself now functioned on foreign models. The boyar families of Old Russian chieftains became feudal nobility, as in England and France. His aim was to create above the rural population a "society" that would be unified as to dress, customs, language, and thought. And soon an upper social stratum actually formed in the cities, having a thin Western veneer. It played at erudition like the Germans, and took on esprit and manners like the French. The entire corpus of Western Rationalism made its entry -- scarcely understood, undigested, and with fateful consequences. Catherine II, a German, found it necessary to send writers such as Novikov and Radishchev into jail and exile because they wished to try out the ideas of the Enlightenment on the political and religious forms of Russia. [5]

(5. "Jehova, Jupiter, Brahma, God of Abraham, God of Moses, God of Confucius, God of Zoroaster, God of Socrates, God of Marcus Aurelius, God of the Christians -- Thou art everywhere the same, eternal God!" (Radishchev).)

And economic life changed also. In addition to its ages-old river traffic, Russia now began to engage in ocean shipping to distant ports. The old merchant tradition of the Stroganovs, with their caravan trade to China, and of the fairs at Nizhni-Novgorod, now received an overlay of Western European "money thinking" in terms of banks and stock exchanges. [6] Next to the old-style handicrafts and the primitive mining techniques in the Urals there appeared factories, machines, and eventually railroads and steamships.

(6. Cf. Decline of the West, II, 480f., 495.)

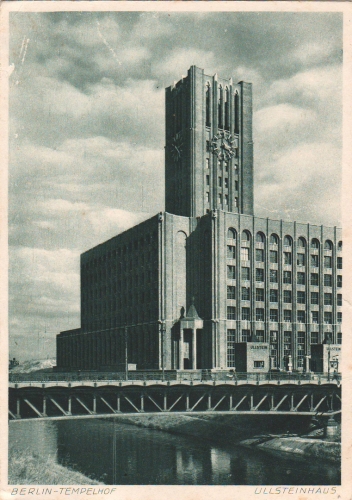

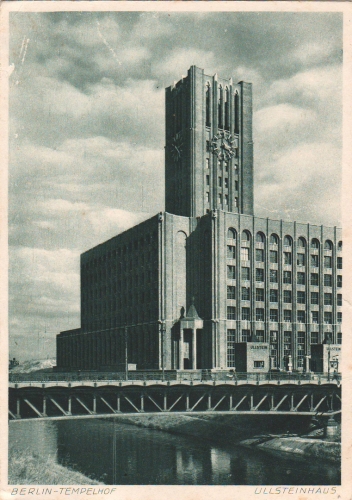

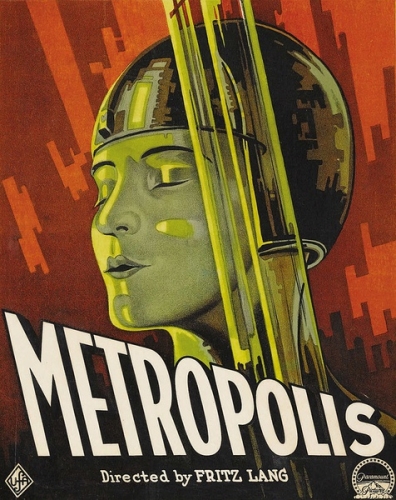

German architecture, 1920s, "Chilehaus" in Hamburg and Berlin Tempelhof

Most important of all, Western-style politics entered the Russian scene. It was supported by an army that no longer conformed to conditions of the wars against the Tartars, Turks, and Kirghiz; it had to be prepared to do battle against Western armies in Western territory, and by its very existence it continually misled the diplomats in Petersburg into thinking that the only political problems lay in the West.

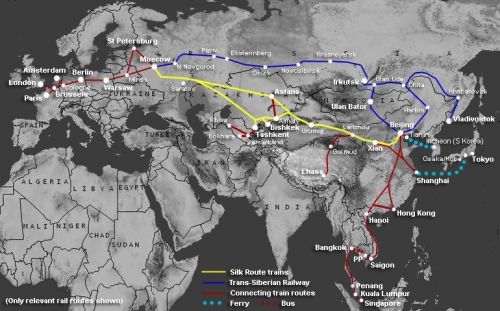

Despite all the weaknesses of an artificial product made of stubborn material, Petrinism was a powerful force during the two hundred years of its duration. It will be possible to assess its true accomplishments only at some distant future time, when we can survey the rubble it will have left behind. It extended "Europe," theoretically at least, to the Urals, and made of it a cultural unity. An empire that stretched to the Bering Strait and the Hindu Kush had been Westernized to the extent that in 1900 there was hardly much difference between cities in Ireland and Portugal and those in Turkestan and the Caucasus. Travel was actually easier in Siberia than in some countries in Western Europe. The Trans-Siberian Railway was the final triumph, the final symbol of the Petrinist will before the collapse.

Yet this mighty exterior concealed an internal disaster. Petrinism was and remained an alien element among the Russian people. In reality there existed not one but two Russias, the apparent and the true, the official and the underground Russia. The foreign element brought with it the poison that caused that immense organism to fall ill and die. The spirit of Western Rationalism of the eighteenth century and Western Materialism of the nineteenth, both remote and incomprehensible to genuine Russian thought, came to lead a grotesque and subversive existence among the intelligentsia in the cities. There arose a type of Russian intellectual who, like the Reformed Turk, the Reformed Chinese, and the Reformed Indian, was mentally and spiritually debased, impoverished, and ruined to the point of cynicism by Western Europe. It began with Voltaire, and continued from Proudhon and Marx to Spencer and Haeckel. In Tolstoy’s day the upper class, irreligious and opposed to all native tradition, preened itself with blasé pretentiousness. Gradually the new world view seeped down to the bohemians in the cities, the students, demagogues, and literati, who in turn took it "to the people" to implant in them a hatred of the Western-style upper classes. The result was doctrinaire bolshevism.

At first, however, it was solely the foreign policy of Russia that made itself painfully felt in the West. The original nature of the Russian people was ignored, or at least not understood. It was nothing but a harmless ethnographic curiosity, occasionally imitated at bals masques and in operettas. Russia meant for us a Great Power in the Western sense, one which played the game of high politics with skill and at times with true mastery.

What we did not notice was that two tendencies, alien and inimical to each other, were operative in Russia. One of these was the ancient, instinctive, unclear, unconscious, and subliminal drive that is present in the soul of every Russian, no matter how thoroughly westernized his conscious life may be -- a mystical yearning for the South, for Constantinople and Jerusalem, a genuine crusading spirit similar to the spirit our Gothic forebears had in their blood but which we hardly can appreciate today. Superimposed on this instinctive drive was the official foreign policy of a Great Power: Petersburg versus Moscow. Behind it lay the desire to play a role on the world stage, to be recognized and treated as an equal in "Europe." Hence the hyper-refined manners and mores, the faultless good taste -- things which had already begun to degenerate in Paris since Napoleon III. The finest tone of Western society was to be found in certain Petersburg circles.

At the same time, this kind of Russian did not really love any of the Western peoples. He admired, envied, ridiculed, or despised them, but his attitude depended practically always on whether Russia stood to gain or lose by them. Hence the respect shown for Prussia during the Wars of Liberation (Russia would have liked to pocket Prussian territory) and for France prior to the World War (the Russians laughed at her senile cries for revanche). Yet, for the ambitious and intelligent upper classes, Russia was the future master of Europe, intellectually and politically. Even Napoleon, in his time, was aware of this. The Russian army was mobilized at the western border; it was of Western proportions and was unmistakably trained for battle on Western terrain against Western foes. Russia’s defeat at the hands of Japan in 1905 can be partly explained by the lack of training for warfare under anything but Western conditions.

Such policies were supported by a network of embassies in the great capitals of the West (which the Soviet government has replaced with Communist party centers for agitation). Catherine the Great took away Poland, and with it the final obstacle between East and West. The climax came with the symbolic journey of Alexander I, the "Savior of Europe," to Paris. At the Congress of Vienna, Russia at times played a decisive role, as also in the Holy Alliance, which Metternich called into being as a bulwark against the Western revolution, and which Nicholas I put to work in 1849 restoring order in the Habsburg state in the interest of his own government.

By means of the successful tradition of Petersburg diplomacy, Russia became more and more involved in great decisions of Western European politics. It took part in all the intrigues and calculations that not only concerned areas remote from Russia, but were also quite incomprehensible to the Russian spirit. The army at the western border was made the strongest in the world, and for no urgent reason -- Russia was the only country no one intended to invade after Napoleon’s defeat, while Germany was threatened by France and Russia, Italy by France and Austria, and Austria by France and Russia. One sought alliance with Russia in order to tip the military balance in one’s favor, thus spurring the ambitions of Russian society toward ever greater efforts in non-Russian interests. All of us grew up under the impression that Russia was a European power and that the land beyond the Volga was colonial territory. The center of gravity of the Empire definitely lay to the west of Moscow, not in the Volga region. And the educated Russians thought the very same way. They regarded the defeat in the Far East in 1905 as an insignificant colonial adventure, whereas even the smallest setback at the western border was in their eyes a scandal, inasmuch as it occurred in full view of the Western nations. In the south and north of the Empire a fleet was constructed, quite superfluous for coastal defense: its sole purpose was to play a role in Western political machinations.

On the other hand, the Turkish Wars, waged with the aim of "liberating" the Christian Balkan peoples, touched the Russian soul more deeply. Russia as the heir to Turkey -- that was a mystical idea. There were no differences of opinion on this question. That was the Will of God. Only the Turkish Wars were truly popular wars in Russia. In 1807 Alexander I feared, not without reason, that he might be assassinated by an officers’ conspiracy. The entire officers’ corps preferred a war against the Turks to one against Napoleon. This led to Alexander’s alliance with Napoleon at Tilsit, which dominated world politics until 1812. It is characteristic how Dostoyevsky, in contrast to Tolstoy, became ecstatic over the Turkish War in 1877. He suddenly came alive, constantly wrote down his metaphysical visions, and preached the religious mission of Russia against Byzantium. But the final portion of Anna Karenina was denied publication by the Russian Messenger, for one did not dare to offer Tolstoy’s skepticism to the public.

As I have mentioned, the educated, irreligious, Westernized Russians also shared the mystical longing for Jerusalem, the Kiev monk’s notion of the mother country as the "Third Rome," which after Papal Rome and Luther’s Wittenberg was to take the fulfillment of Christ’s message to the Jerusalem of the apostles. This barely conscious national instinct of all Russians opposes any power that might erect political barricades on the path that leads to Jerusalem by way of Byzantium. In all other countries such political obstacles would simply disturb either national conceit (in the West) or national apathy (in the Far East); in Russia, the mystical soul of the people itself was pierced and profoundly agitated. Hence the brilliant successes of the Slavophil movement, which was not so much interested in winning over Poles and Czechs as in gaining a foothold among the Slavs in the Christian Balkan countries, the neighbors of Constantinople. Even at an earlier date, the Holy War against Napoleon and the Burning of Moscow had involved the emotions of the entire Russian people. This was not just because of the invasion and plundering of the Russian countryside, but because of Napoleon’s obvious long-range plans. In 1809 he had taken over the Illyrian provinces (the present Yugoslavia) and thus became master of the Adriatic. This had decisively strengthened his influence on Turkey to the disadvantage of Russia, and his next step would be, in alliance with Turkey and Persia, to open up the path to India, either from Illyria or from Moscow itself. The Russians’ hatred of Napoleon was later transferred to the Habsburg monarchy, when its designs on Turkish territory -- in Metternich’s time the Danubian principalities, and after 1878 Saloniki -- endangered Russian moves toward the south. Following the Crimean War they extended their hatred to include Great Britain, when that nation appeared to lay claim to Turkish lands by blockading the Straits and later by occupying Egypt and Cyprus.

Finally, Germany too became the object of this hatred, which goes very deep and cannot be allayed by practical considerations. After 1878, Germany neglected its role as a Russian ally to became more and more the protector and preserver of the crumbling Habsburg state, and thereby also, despite Bismarck’s warning, the supporter of Austro-Hungarian intentions in the Balkans. The German government showed no understanding of the suggestion made by Count Witte, the last of the Russian diplomats friendly to Germany, to choose between Austria and Russia. We could have had a reliable ally in Russia if we had been willing to loosen our ties to Austria. A total reorientation of German policy might have been possible as late as 1911.

Following the Congress of Berlin, hatred of Germany began to spread to all of Russian society, for Bismarck succeeded in restraining Russian diplomacy in the interest of world peace and maintaining the balance of power in "Europe." From the German point of view this was probably correct, and in any case it was a master stroke of Bismarckian statesmanship. But in the eyes of Petersburg it was a mistake, for it deprived the Russian soul of the hope of winning Turkey, and favored England and Austria. And this Russian soul was one of the imponderables that defied diplomatic treatment. Hostility to Germany kept on growing and eventually entered all levels of Russian urban society. It was diverted momentarily when Japanese power, rising up suddenly and broadening the horizons of world politics, forced Russia to experience the Far East as a danger zone. But that was soon forgotten, especially since Germany was so grotesquely inept as to understand neither the immediate situation nor the future possibilities. In time, the senseless idea of the Berlin-Baghdad Railway came up; Germany now seemed intent on capturing full control of this path to Constantinople, a move which would have benefitted neither German politics nor the German economy.

Just as in the field of politics, the economic life of Russia was divided into two main tendencies -- the one active and aggressive, the other passive. The passive element was represented by the Russian peasantry with its primitive agrarian economy; [7] by the old-style merchants with their fairs, caravans, and Volga barges; by Russian craftsmen; and finally by the primitive mining enterprises in the Urals, which developed out of the ancient techniques of pre-Christian "blacksmith tribes," independent of Western mining methods and experience. The forging of iron was invented in Russia in the second millennium B.C. -- the Greeks retained a vague recollection of the beginning of this art. This simple and traditional form of economy gradually found a powerful competitor in the civilized world of Western-style urban economy, with its banks, stock exchanges, factories, and railroads. Then it was money economy versus goods economy; each of these forms of economic existence abhors the other, each tries to attack and annihilate the other.

(7. On the contrast between agrarian and urban economy, see Decline of the West, II, 477ff.)

The Petrinist state needed a money economy in order to pay for its Westernized politics, its army, and its administrative hierarchy, which was laced with primitive corruption. Incidentally, this form of corruption was habitual public practice in Russia; it is a necessary psychological concomitant of an economy based on the exchange of goods, and is fundamentally different from the clandestine corruption practiced by Western European parliamentarians. The state protected and supported economic thinking that was oriented toward Western capitalism, a type of thinking that Russia neither created nor really understood, but had imported and now had to manage. Furthermore, Russia had also to face its doctrinary opposite, the economic theory of communism. Communism was in fact inseparable from Western economic thinking. It was the Marxist capitalism of the lower class, preached by students and agitators as a vague gospel to the masses in the Petrinist cities.

Still, the decisive and truly agitating factor for Russia’s future was not this literary, theoretical trend in the urban underground. It was, rather, the Russians’ profound, instinctively religious abhorrence of all Western economic practices. They considered "money" and all the economic schemes derived from it, socialistic as well as capitalistic, as sinful and satanic. This was a genuine religious feeling, much like the Western emotion which, during the Gothic centuries, opposed the economic practices of the Arabic-Jewish world and led to the prohibition for Christians of money-lending for interest. In the West, such attitudes had for centuries been little more than a cliché for chapel and pulpit, but now it became an acute spiritual problem in Russia. It caused the suicide of numerous Russians who were seized by "terror of the surplus value," whose primitive thought and emotions could not imagine a way of earning a living that would not entail the "exploitation" of "fellow human beings." This genuine Russian sentiment saw in the world of capitalism an enemy, a poison, the great sin that it ascribed to the Petrinist state despite the deep respect felt for "Little Father," the Tsar.

Such, then, are the deep and manifold roots of the Russian philosophy of intellectual nihilism, which began to grow at the time of the Crimean War and which produced as a final fruit the bolshevism that destroyed the Petrinist state in 1917, replacing it with something that would have been absolutely impossible in the West. Contained within this movement is the orthodox Slavophils’ hatred of Petersburg and all it stood for, [8] the peasants’ hatred of the mir, the type of village commune that contradicted the rural concept of property passed down through countless family generations, as well as every Russian’s hatred of capitalism, industrial economy, machines, railroads, and the state and army that offered protection to this cynical world against an eruption of Russian instincts. It was a primeval religious hatred of uncomprehended forces that were felt to be godless, that one could not change and thus wished to destroy, in order that life could go on in the old-fashioned way.

(8. "The first requirement for the liberation of popular feeling in Russia is to hate Petersburg with heart and soul" (Aksakov to Dostoyevsky). Cf. Decline of the West, II, 193ff.)

The peasants detested the intelligentsia and its agitating just as strongly as they detested what these people were agitating against. Yet in time the agitation brought a small clique of clever but by and large mediocre personalities to the forefront of power. Even Lenin’s creation is Western, it is Petersburg -- foreign, inimical, and despised by the majority of Russians. Some day, in some way or other, it will perish. It is a rebellion against the West, but born of Western ideas. It seeks to preserve the economic forms of industrial labor and capitalist speculation as well as the authoritarian state, except that it has replaced the Tsarist regime and private capitalist enterprise with an oligarchy and state capitalism, calling itself communism out of deference to doctrine.

It is a new victory for Petersburg over Moscow and, without any doubt, the final and enduring act of self-destruction committed by Petrinism from below. The actual victim is precisely the element that sought to liberate itself by means of the rebellion: the true Russian, the peasant and craftsman, the devout man of religion. Western revolutions such as the English and French seek to improve organically evolved conditions by means of theory, and they never succeed. In Russia, however, a whole world was made to vanish without resistance. Only the artificial quality of Peter the Great’s creation can explain the fact that a small group of revolutionaries, almost without exception dunces and cowards, has had such an effect. Petrinism was an illusion that suddenly burst.

The bolshevism of the early years has thus had a double meaning. It has destroyed an artificial, foreign structure, leaving only itself as a remaining integral part. But beyond this, it has made the way clear for a new culture that will some day awaken between "Europe" and East Asia. It is more a beginning than an end. It is temporary, superficial, and foreign only insofar as it represents the self-destruction of Petrinism, the grotesque attempt systematically to overturn the social superstructure of the nation according to the theories of Karl Marx. At the base of this nation lies the Russian peasantry, which doubtless played a more important role in the success of the 1917 Revolution than the intellectual crowd is willing to admit. These are the devout peasants of Russia who, although they do not yet fully realize it, are the archenemies of bolshevism and are oppressed by it even worse than they were by the Mongols and the old tsars. For this very reason, despite the hardships of the present, the peasantry will some day become conscious of its own will, which points in a wholly different direction.

The peasantry is the true Russian people of the future. It will not allow itself to be perverted and suffocated, and without a doubt, no matter how slowly, it will replace, transform, control, or annihilate bolshevism in its present form. How that will happen, no one can tell at the moment. It depends, among other things, on the appearance of decisive personalities, who, like Genghis Khan, Ivan IV, Peter the Great, and Lenin, can seize Destiny by their iron hand. Here, too, Dostoyevsky stands against Tolstoy as a symbol of the future against the present. Dostoyevsky was denounced as a reactionary because in his Possessed he no longer even recognized the problems of nihilism. For him, such things were just another aspect of the Petrinist system. But Tolstoy, the man of good society, lived in this element; he represented it even in his rebellion, a protest in Western form against the West. Tolstoy, and not Marx, was the leader to bolshevism. Dostoyevsky is its future conqueror.

There can be no doubt: a new Russian people is in the process of becoming. Shaken and threatened to the very soul by a frightful destiny, forced to an inner resistance, it will in time become firm and come to bloom. It is passionately religious in a way we Western Europeans have not been, indeed could not have been, for centuries. As soon as this religious drive is directed toward a goal, it possesses an immense expansive potential. Unlike us, such a people does not count the victims who die for an idea, for it is a young, vigorous, and fertile people. The intense respect enjoyed over the past centuries by the "holy peasants" whom the regime often exiled to Siberia or liquidated in some other way -- such figures as the priest John of Kronstadt, even Rasputin, but also Ivan and Peter the Great -- will awaken a new type of leaders, leaders to new crusades and legendary conquests. The world round about, filled with religious yearning but no longer fertile in religious concerns, is torn and tired enough to allow it suddenly to take on a new character under the proper circumstances. Perhaps bolshevism itself will change in this way under new leaders; but that is not very probable. For this ruling horde -- it is a fraternity like the Mongols of the Golden Horde -- always has its sights set on the West as did Peter the Great, who likewise made the land of his dreams the goal of his politics. But the silent, deeper Russia has already forgotten the West and has long since begun to look toward Near and East Asia. It is a people of the great inland expanses, not a maritime people.

An interest in Western affairs is upheld only by the ruling group that organizes and supports the Communist parties in the individual countries -- without, as I see it, any chance of success. It is simply a consequence of Marxist theory, not an exercise in practical politics. The only way that Russia might again direct its attention to the West -- with disastrous results for both sides -- would be for other countries (Germany, for instance) to commit serious errors in foreign policy, which could conceivably result in a "crusade" of the Western powers against bolshevism -- in the interest, of course, of Franco-British financial capital. Russia’s secret desire is to move toward Jerusalem and Central Asia, and "the" enemy will always be the one who blocks those paths. The fact that England established the Baltic states and placed them under its influence, thereby causing Russia to lose the Baltic Sea, has not had a profound effect. Petersburg has already been given up for lost, an expendable relic of the Petrinist era. Moscow is once again the center of the nation. But the destruction of Turkey, the partition of that country into French and English spheres of influence, France’s establishment of the Little Entente which closed off and threatened the area from Rumania southwards, French attempts to win control of the Danubian principalities and the Black Sea by aiding the reconstruction of the Hapsburg state -- all these events have made England and, above all, France the heirs to Russian hatred. What the Russians see is the revivification of Napoleonic tendencies; the crossing of the Beresina was perhaps not, after all, the final symbolic event in that movement. Byzantium is and remains the Sublime Gateway to future Russian policy, while, on the other side, Central Asia is no longer a conquered area but part of the sacred earth of the Russian people.

In the face of this rapidly changing, growing Russia, German policy requires the tactical skill of a great statesman and expert in Eastern affairs, but as yet no such man has made his appearance. It is clear that we are not the enemies of Russia; but whose friends are we to be -- of the Russia of today, or of the Russia of tomorrow? Is it possible to be both, or does one exclude the other? Might we not jeopardize such friendship by forming careless alliances?

Similarly obscure and difficult are our economic connections, the actual ones and the potential ones. Politics and economics are two very different aspects of life, different in concept, methods, aims, and significance for the soul of a people. This is not realized in the age of practical materialism, but that does not make it any less fatefully true. Economics is subordinate to politics; it is without question the second and not the first factor in history. The economic life of Russia is only superficially dominated by state capitalism. At its base it is subject to attitudes that are virtually religious in nature. At any rate it is not at all the same thing as top-level Russian politics. Moreover, it is very difficult to predict its short and long-range trends, and even more difficult to control these trends from abroad. The Russia of the last tsars gave the illusion of being an economic complex of Western stamp. Bolshevist Russia would like to give the same illusion; with its communist methods it would even like to become an example for the West. Yet in reality, when considered from the standpoint of Western economics, it is one huge colonial territory where the Russians of the farmlands and small towns work essentially as peasants and craftsmen. Industry and the transportation of industrial products over the rail networks, as well as the process of wholesale distribution of such products, are and will always remain inwardly foreign to this people. The businessman, the factory head, the engineer and inventor are not "Russian" types. As a people, no matter how far individuals may go toward adapting to modern patterns of world economics, the true Russians will always let foreigners do the kind of work they reject because they are inwardly not suited to it. A close comparison with the Age of the Crusades will clarify what I have in mind. [9] At that time, also, the young peoples of the North were nonurban, committed to an agrarian economy. Even the small cities, castle communities, and princely residences were essentially marketplaces for agricultural produce. The Jews and Arabs were a full thousand years "older," and functioned in their ghettos as experts in urban money economy. The Western European fulfills the same function in the Russia of today.

(9. Cf. Decline of the West, II, Chapters XIII and XIV, "The Form-World of Economic Life.")

Machine industry is basically non-Russian in spirit, and the Russians will forever regard it as alien, sinful, and diabolical. They can bear with it and even respect it, as the Japanese do, as a means toward higher ends, for one casts out demons by the prince of demons. But they can never give their soul to it as did the Germanic nations, which created it with their dynamic sensibility as a symbol and method of their struggling existence. In Russia, industry will always remain essentially the concern of foreigners. But the Russians will be able to distinguish sensitively between what is to their own and what is to the foreigners’ advantage.

As far as "money" is concerned, for the Russians the cities are markets for agricultural commodities; for us they have been since the eighteenth century the centers for the dynamics of money. "Money thinking" will be impossible for the Russians for a long time to come. For this reason, as I have explained, Russia is regarded as a colony by foreign business interests. Germany will be able to gain certain advantages from its proximity to the country, particularly in light of the fact that both powers have the same enemy, the financial interest-groups of the Allied nations.

Yet the German economy can never exploit these opportunities without support from superior politics. Without such support a chaotic seizure of opportunities will ensue, with dire consequences for the future. The economic policy of France has been for centuries, as a result of the sadistic character of the French people, myopic and purely destructive. And a serious German policy in economic affairs simply does not exist.

Therefore it is the prime task of German business to help create order in German domestic affairs, in order to set the stage for a foreign policy that will understand and meet its obligations. Business has not yet grasped the immense economic significance of this domestic task. It is decidedly not a question, as common prejudice would have it, of making politics submit to the momentary interests of single groups, such as has already occurred by means of the worst kind of politics imaginable, party politics. It is not a question of advantages that might last for just a few years. Before the war it was the large agricultural interests, and since the war the large industrial interests, that attempted to focus national policy on the obtaining of temporary advantages, and the results were always nil. But the time for short-range tactics is over. The next decades will bring problems of world-historical dimensions, and that means that business must at all times be subordinate to national politics, not the other way around. Our business leaders must learn to think exclusively in political terms, not in terms of "economic politics." The basic requirement for great economic opportunity in the East is thus order in our politics at home.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg