AlternativeRight.Com & http://attackthesystem.com

The dramatic changes that had occurred in Western society over the course of the nineteenth century had dramatically impacted the thinking of its leading intellects. The growth of industrial civilization has raised the general standards of living to levels that were hitherto not even dreamed of, and the rising incomes of the traditionally exploited industrial working class were finally allowing even the proletariat to share in at least some middle class comforts. The rise of new political ideologies such as liberalism and democracy had imparted to ordinary people political and legal rights that were previously reserved only for the nobility. Health standards also increased significantly as industrial civilization expanded and life expectancy began to grow longer. Scientific discovery and technological innovation exploded during the same era and human beings began to marvel at what they had accomplished and might be able to accomplish in the future. Religion-driven superstitions had begun to wane and the religious persecutions of the past had dwindled to near non-existence. Societies became ever more complex and out of this complexity came the need for an ever expanding class of specialists and more scientific approaches to social management. While only a hundred years had passed between the world as it was in 1800 and the world of 1900, the changes that had occurred in the previous century were so profound that the time difference might as well have been thousands of years.

The profundity of this civilization-wide change inspired the leading thinkers of the era to tremendous confidence and optimism regarding the future and human capabilities. If one surveys the literature of utopian writers of the era one immediately observes that many of these authors expressed a confidence in the future that now seems as quaint as it is absurd. The horrors of the twentieth century, with its genocides, total wars, atomic weaponry, and unprecedented levels of tyranny would subsequently shatter the naïve idealism of many who had previously viewed the advent of that century with great hopes that often approached the fantastic. The early twentieth century was a time of joyous naivete. Bertrand Russell would later insist that no one who was born after the beginning of the Great War which broke out in 1914 would ever know what it was like to be truly happy.

|

| “Pick a star, any star” – the retro-futuristic optimism of the past |

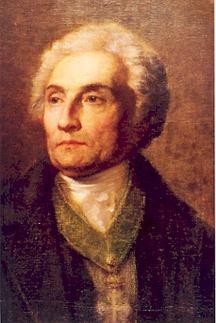

But G. K. Chesterton, while far from being a cynical or overly pessimistic figure, was not one who shared in this optimism. Indeed, he was one who understood the potential horrors that could be unleashed by the new society and new modes of thought as clearly as any other. To Chesterton, the progressives of his time were over confident to the point of arrogance and failed to recognize the dangers that might befall mankind as humanity boldly forged its way into the future. Perhaps one of Chesterton’s most prescient works of social criticism is Eugenics and Other Evils, published in 1917. [1] At the time the eugenics movement that was largely traceable to the thought of Darwin’s cousin, Francis Galton, had become a popular one in the world’s most advanced nations such as England, America, and Germany. It was a movement that in its day was regarded as progressive, enlightened and as applying scientific principles to the betterment of human society and even the human species itself. Its supporters included many leading thinkers and public figures of the era including Winston Churchill, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, John Maynard Keynes, Anthony Ludovici, Madison Grant, and Chesterton’s friends Wells and Shaw. Yet Chesterton was one of the earliest critics of the eugenics movement and regarded it as representing dangerous presumptions on the part of its proponents that would likely lead to horrific abuses of liberty and violations of the individual person which it eventually did.

One of Chesterton’s most persistent targets was the growing secularism of his era, a trend which continues to the present time. That Chesterton was a man of profound faith even as religion was being dwarfed by science among thinking and educated people during his time solidifies Chesterton’s role as a true intellectual maverick. It is this aspect of Chesterton’s thought that as much as anything else continues to win him the admiration of those who remain believers even during the twenty-first century. Chesterton was always a man of spiritual interests and even as a young man toyed with occultism and ouija boards. The development of his spiritual thinking later led him to regard himself and an “orthodox” Christian and Chesterton formally converted to Catholicism in 1922 at the age of forty-six. His admirer C. S. Lewis considered Chesterton’s writings on Christian subjects to be among the very best works in Christian apologetics.

In the intellectual climate of the early twenty-first century, religious thinking has fallen into even greater disrepute than it possessed in the early twentieth century. In relatively recent times, popular culture has produced a number of writers whose open contempt for religious believers has earned them a great deal of prominence. While intelligent believers who can offer thoughtful defenses of their views certainly still exist, it is also that case that religious belief or practice is at its lowest point yet in terms of popular enthusiasm in the Western world. Less than five percent of the British population attends religious services regularly and even in the United States, with its comparatively large population of religious fundamentalists, secularism has become the fastest growing religious perspective. Chesterton would no doubt be regarded as a rather anachronistic figure in such a cultural climate.

|

| Abandoned church |

The contemporary liberal and left-wing stereotype of a religious believer is that of an ignorant or narrow-minded bigot who is incapable of flexibility in his thinking and reacts with intolerance to those holding different points of view. Certainly, there are plenty of religious people who fit such stereotypes just as overly rigid and dogmatic persons can be found among adherents of any system of thought. Yet, a survey of both Chesterton’s writings on religion and his correspondence with friends of a secular persuasion indicates that Chesterton was the polar opposite of a bigoted, intolerant, religious fanatic. In his Christian apologetic work Orthodoxy, Chesterton wrote,

“To hope for all souls is imperative, and it is quite tenable that their salvation is inevitable…In Christian morals, in short, it is wicked to call a man ‘damned’: but it is strictly religious and philosophic to call him damnable.”

Of his friend Shaw, he said, “In a sweeter and more solid civilization he would have been a great saint.”

In his latter years when he knew he was dying, H. G. Wells wrote to Chesterton, “If after all my Atheology turns out wrong and your Theology right I feel I shall always be able to pass into Heaven (if I want to) as a friend of G.K.C.’s. Bless you.” Chesterton wrote in response:

“If I turn out to be right, you will triumph, not by being a friend of mine, but by being a friend of Man, by having done a thousand things for men like me in every way from imagination to criticism. The thought of the vast variety of that work, and how it ranges from towering visions to tiny pricks of humor, overwhelmed me suddenly in retrospect; and I felt we have none of us ever said enough…Yours always, G. K. Chesterton.” [2]

It was also during Chesterton’s era that the classical socialist movement was initially starting to become powerful through the trade unions and labor parties and virtually all leading intellectuals of the era professed fidelity to the ideals of socialism. Yet just as Chesterton was a prescient critic of eugenics, he likewise offered an equally prescient critique of the totalitarian implications of state socialism. Because of this, he was often labeled a reactionary or conservative apologist for the plutocratic overlords of industrial capitalism by the Marxists of his era. But Chesterton was no friend of those who would exploit the poor and workings classes and was in fact a staunch critic of the industrial system as it was in the England of his era. “Who except a devil from Hell ever defended it?” he was alleged to have said when asked about capitalism as it was practiced in his day. [3]

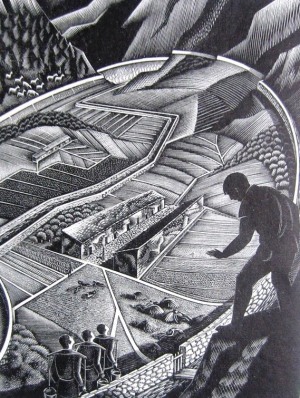

Indeed, Chesterton’s criticisms of both industrial capitalism and state socialism led to the development of one of the most well-known and interesting aspects of his thought, the unique economic philosophy of distributism. Along with his dear friend and fellow Catholic traditionalist Hilaire Belloc (Shaw coined the term “Chesterbelloc” to describe the pair as inseparable as they were), Chesterton suggested the creation of an economic system where productive property would be spread to as many owners of capital as possible thereby producing many “small capitalists” rather than having capital concentrated into the hands of a few plutocrats, trusts, or the state itself.

The prevailing trends of the twentieth century were towards ever greater concentrations of power in large scale, pyramid-like institutions and ever expanding bureaucratic profligacy. Chesterton’s and Belloc’s economic ideas were frequently dismissed as quaint and archaic. However, technological developments in the cyber age have once again opened the door for exciting new possibilities concerning the prospects for the decentralization of economic life. Far from being anachronistic reactionaries, perhaps Chesterton and his friend Belloc were instead futuristic visionaries far ahead of their time.

It is clear enough that Chesterton was in many ways a model for what a public intellectual should be. He was a fiercely and genuinely independent thinker and one who stuck to his convictions with courage. Chesterton never hesitated to buck the prevailing trends of his day and was not concerned about earning the opprobrium of the chattering classes by doing so. He was above all a man of character, committed to intellectual integrity, sincere in his convictions, tolerant in his religious faith, and charitable in his relations with others. In his intellectual life, he wisely and quixotically criticized the worst excesses of the intellectual culture of his time. The twentieth century might have been a happier time if the counsel of G. K. Chesterton had been heeded.

NOTES:

[1] Chesterton, Gilbert Keith. Eugenics and Other Evils. Reprinted by CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 1st edition (November 20, 2012). Originally published in 1917.

[2] Babinski, Edward T. Chesterton and Univeralism. Archived at http://www.tentmaker.org/biographies/chesterton.htm. Accessed on March 12, 2013.

[3] Friedman, David D. G. K. Chesterton-An Author Review, The Machinery of Freedom: Guide to Radical Capitalism. Second Edition. Archived at http://daviddfriedman.com/The_Machinery_of_Freedom_.pdf. Accessed on March 12, 2013.

Originally published in Chesterton: Thoughts & Perspectives, Volume Thirteen (edited by Troy Southgate) published by Black Front Press.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg Though Antoine Compagnon’s eloquently written and extensively researched essay won a number of prizes and set off a stir among France’s literati, there is little to recommend it here—except for its central theme, which speaks, however implicitly, to the great question of our age in defining and classifying a form of thought whose mission is to arrest modernity’s seemingly heedless advance toward self-destruction.

Though Antoine Compagnon’s eloquently written and extensively researched essay won a number of prizes and set off a stir among France’s literati, there is little to recommend it here—except for its central theme, which speaks, however implicitly, to the great question of our age in defining and classifying a form of thought whose mission is to arrest modernity’s seemingly heedless advance toward self-destruction.