The Rockford Institute’s publication of Organizing the Revolution marks the first appearance in our language of an historian whose insights apply not only to the French Revolution but to much of modern politics as well.

Augustin Cochin (1876–1916) was born into a family that had distinguished itself for three generations in the antiliberal “Social Catholicism” movement. He studied at the Ecole des Chartes and began to specialize in the study of the Revolution in 1903. Drafted in 1914 and wounded four times, he continued his researches during periods of convalescence. But he always requested to be returned to the front, where he was killed on July 8, 1916 at the age of thirty-nine.

Cochin was a philosophical historian in an era peculiarly unable to appreciate that rare talent. He was trained in the supposedly “scientific” methods of research formalized in his day under the influence of positivism, and was in fact an irreproachably patient and thorough investigator of primary archives. Yet he never succumbed to the prevailing notion that facts and documents would tell their own story in the absence of a human historian’s empathy and imagination. He always bore in mind that the goal of historical research was a distinctive type of understanding.

Both his archival and his interpretive labors were dedicated to elucidating the development of Jacobinism, in which he (rightly) saw the central, defining feature of the French Revolution. François Furet wrote: “his approach to the problem of Jacobinism is so original that it has been either not understood or buried, or both.”[1]

Most of his work appeared only posthumously. His one finished book is a detailed study of the first phase of the Revolution as it played out in Brittany: it was published in 1925 by his collaborator Charles Charpentier. He had also prepared (with Charpentier) a complete collection of the decrees of the revolutionary government (August 23, 1793–July 27, 1794). His mother arranged for the publication of two volumes of theoretical writings: The Philosophical Societies and Modern Democracy (1921), a collection of lectures and articles; and The Revolution and Free Thought (1924), an unfinished work of interpretation. These met with reviews ranging from the hostile to the uncomprehending to the dismissive.

“Revisionist” historian François Furet led a revival of interest in Cochin during the late 1970s, making him the subject of a long and appreciative chapter in his important study Interpreting the French Revolution and putting him on a par with Tocqueville. Cochin’s two volumes of theoretical writings were reprinted shortly thereafter by Copernic, a French publisher associated with GRECE and the “nouvelle droit.”

The book under review consists of selections in English from these volumes. The editor and translator may be said to have succeeded in their announced aim: “to present his unfinished writings in a clear and coherent form.”

Between the death of the pioneering antirevolutionary historian Hippolyte Taine in 1893 and the rise of “revisionism” in the 1960s, study of the French Revolution was dominated by a series of Jacobin sympathizers: Aulard, Mathiez, Lefevre, Soboul. During the years Cochin was producing his work, much public attention was directed to polemical exchanges between Aulard, a devotee of Danton, and his former student Mathiez, who had become a disciple of Robespierre. Both men remained largely oblivious to the vast ocean of assumptions they shared.

Cochin published a critique of Aulard and his methods in 1909; an abridged version of this piece is included in the volume under review. Aulard’s principal theme was that the revolutionary government had been driven to act as it did by circumstance:

This argument [writes Cochin] tends to prove that the ideas and sentiments of the men of ’93 had nothing abnormal in themselves, and if their deeds shock us it is because we forget their perils, the circumstances; [and that] any man with common sense and a heart would have acted as they did in their place. Aulard allows this apology to include even the very last acts of the Terror. Thus we see that the Prussian invasion caused the massacre of the priests of the Abbey, the victories of la Rochejacquelein [in the Vendée uprising] caused the Girondins to be guillotined, [etc.]. In short, to read Aulard, the Revolutionary government appears a mere makeshift rudder in a storm, “a wartime expedient.” (p. 49)

Aulard had been strongly influenced by positivism, and believed that the most accurate historiography would result from staying as close as possible to documents of the period; he is said to have conducted more extensive archival research than any previous historian of the Revolution. But Cochin questioned whether such a return to the sources would necessarily produce truer history:

Mr. Aulard’s sources—minutes of meetings, official reports, newspapers, patriotic pamphlets—are written by patriots [i.e., revolutionaries], and mostly for the public. He was to find the argument of defense highlighted throughout these documents. In his hands he had a ready-made history of the Revolution, presenting—beside each of the acts of “the people,” from the September massacres to the law of Prairial—a ready-made explanation. And it is this history he has written. (p. 65)

In fact, says Cochin, justification in terms of “public safety” or “self- defense” is an intrinsic characteristic of democratic governance, and quite independent of circumstance:

In fact, says Cochin, justification in terms of “public safety” or “self- defense” is an intrinsic characteristic of democratic governance, and quite independent of circumstance:

When the acts of a popular power attain a certain degree of arbitrariness and become oppressive, they are always presented as acts of self-defense and public safety. Public safety is the necessary fiction in democracy, as divine right is under an authoritarian regime. [The argument for defense] appeared with democracy itself. As early as July 28, 1789 [i.e., two weeks after the storming of the Bastille] one of the leaders of the party of freedom proposed to establish a search committee, later called “general safety,” that would be able to violate the privacy of letters and lock people up without hearing their defense. (pp. 62–63)

(Americans of the “War on Terror” era, take note.)

But in fact, says Cochin, the appeal to defense is nearly everywhere a post facto rationalization rather than a real motive:

Why were the priests persecuted at Auch? Because they were plotting, claims the “public voice.” Why were they not persecuted in Chartes? Because they behaved well there.

How often can we not turn this argument around?

Why did the people in Auch (the Jacobins, who controlled publicity) say the priests were plotting? Because the people (the Jacobins) were persecuting them. Why did no one say so in Chartes? Because they were left alone there.

In 1794 put a true Jacobin in Caen, and a moderate in Arras, and you could be sure by the next day that the aristocracy of Caen, peaceable up till then, would have “raised their haughty heads,” and in Arras they would go home. (p. 67)

In other words, Aulard’s “objective” method of staying close to contemporary documents does not scrape off a superfluous layer of interpretation and put us directly in touch with raw fact—it merely takes the self-understanding of the revolutionaries at face value, surely the most naïve style of interpretation imaginable. Cochin concludes his critique of Aulard with a backhanded compliment, calling him “a master of Jacobin orthodoxy. With him we are sure we have the ‘patriotic’ version. And for this reason his work will no doubt remain useful and consulted” (p. 74). Cochin could not have foreseen that the reading public would be subjected to another half century of the same thing, fitted out with ever more “original documentary research” and flavored with ever increasing doses of Marxism.

But rather than attending further to these methodological squabbles, let us consider how Cochin can help us understand the French Revolution and the “progressive” politics it continues to inspire.

It has always been easy for critics to rehearse the Revolution’s atrocities: the prison massacres, the suppression of the Vendée, the Law of Suspects, noyades and guillotines. The greatest atrocities of the 1790s from a strictly humanitarian point of view, however, occurred in Poland, and some of these were actually counter-revolutionary reprisals. The perennial fascination of the French Revolution lies not so much in the extent of its cruelties and injustices, which the Caligulas and Genghis Khans of history may occasionally have equaled, but in the sense that revolutionary tyranny was something different in kind, something uncanny and unprecedented. Tocqueville wrote of

something special about the sickness of the French Revolution which I sense without being able to describe. My spirit flags from the effort to gain a clear picture of this object and to find the means of describing it fairly. Independently of everything that is comprehensible in the French Revolution there is something that remains inexplicable.

Part of the weird quality of the Revolution was that it claimed, unlike Genghis and his ilk, to be massacring in the name of liberty, equality, and fraternity. But a deeper mystery which has fascinated even its enemies is the contrast between its vast size and force and the negligible ability of its apparent “leaders” to unleash or control it: the men do not measure up to the events. For Joseph de Maistre the explanation could only be the direct working of Divine Providence; none but the Almighty could have brought about so great a cataclysm by means of such contemptible characters. For Augustin Barruel it was proof of a vast, hidden conspiracy (his ideas have a good claim to constitute the world’s original “conspiracy theory”). Taine invoked a “Jacobin psychology” compounded of abstraction, fanaticism, and opportunism.

Cochin found all these notions of his antirevolutionary predecessors unsatisfying. Though Catholic by religion and family background, he quite properly never appeals to Divine Providence in his scholarly work to explain events (p. 71). He also saw that the revolutionaries were too fanatical and disciplined to be mere conspirators bent on plunder (pp. 56–58; 121–122; 154). Nor is an appeal to the psychology of the individual Jacobin useful as an explanation of the Revolution: this psychology is itself precisely what the historian must try to explain (pp. 60–61).

Cochin viewed Jacobinism not primarily as an ideology but as a form of society with its own inherent rules and constraints independent of the desires and intentions of its members. This central intuition—the importance of attending to the social formation in which revolutionary ideology and practice were elaborated as much as to ideology, events, or leaders themselves—distinguishes his work from all previous writing on the Revolution and was the guiding principle of his archival research. He even saw himself as a sociologist, and had an interest in Durkheim unusual for someone of his Catholic traditionalist background.

The term he employs for the type of association he is interested in is société de pensée, literally “thought-society,” but commonly translated “philosophical society.” He defines it as “an association founded without any other object than to elicit through discussion, to set by vote, to spread by correspondence—in a word, merely to express—the common opinion of its members. It is the organ of [public] opinion reduced to its function as an organ” (p. 139).

It is no trivial circumstance when such societies proliferate through the length and breadth of a large kingdom. Speaking generally, men are either born into associations (e.g., families, villages, nations) or form them in order to accomplish practical ends (e.g., trade unions, schools, armies). Why were associations of mere opinion thriving so luxuriously in France on the eve of the Revolution? Cochin does not really attempt to explain the origin of the phenomenon he analyzes, but a brief historical review may at least clarify for my readers the setting in which these unusual societies emerged.

About the middle of the seventeenth century, during the minority of Louis XIV, the French nobility staged a clumsy and disorganized revolt in an attempt to reverse the long decline of their political fortunes. At one point, the ten year old King had to flee for his life. When he came of age, Louis put a high priority upon ensuring that such a thing could never happen again. The means he chose was to buy the nobility off. They were relieved of the obligations traditionally connected with their ancestral estates and encouraged to reside in Versailles under his watchful eye; yet they retained full exemption from the ruinous taxation that he inflicted upon the rest of the kingdom. This succeeded in heading off further revolt, but also established a permanent, sizeable class of persons with a great deal of wealth, no social function, and nothing much to do with themselves.

The salon became the central institution of French life. Men and women of leisure met for gossip, dalliance, witty badinage, personal (not political) intrigue, and discussion of the latest books and plays and the events of the day. Refinement of taste and the social graces reached an unusual pitch. It was this cultivated leisure class which provided both setting and audience for the literary works of the grand siècle.

The common social currency of the age was talk: outside Jewish yeshivas, the world had probably never beheld a society with a higher ratio of talk to action. A small deed, such as Montgolfier’s ascent in a hot air balloon, could provide matter for three years of self-contented chatter in the salons.

Versailles was the epicenter of this world; Paris imitated Versailles; larger provincial cities imitated Paris. Eventually there was no town left in the realm without persons ambitious of imitating the manners of the Court and devoted to cultivating and discussing whatever had passed out of fashion in the capital two years earlier. Families of the rising middle class, as soon as they had means to enjoy a bit of leisure, aspired to become a part of salon society.

Toward the middle of the eighteenth century a shift in both subject matter and tone came over this world of elegant discourse. The traditional saloniste gave way to the philosophe, an armchair statesman who, despite his lack of real responsibilities, focused on public affairs and took himself and his talk with extreme seriousness. In Cochin’s words: “mockery replaced gaiety, and politics pleasure; the game became a career, the festivity a ceremony, the clique the Republic of Letters” (p. 38). Excluding men of leisure from participation in public life, as Louis XIV and his successors had done, failed to extinguish ambition from their hearts. Perhaps in part by way of compensation, the philosophes gradually

created an ideal republic alongside and in the image of the real one, with its own constitution, its magistrates, its common people, its honors and its battles. There they studied the same problems—political, economic, etc.—and there they discussed agriculture, art, ethics, law, etc. There they debated the issues of the day and judged the officeholders. In short, this little State was the exact image of the larger one with only one difference—it was not real. Its citizens had neither direct interest nor responsible involvement in the affairs they discussed. Their decrees were only wishes, their battles conversations, their studies games. It was the city of thought. That was its essential characteristic, the one both initiates and outsiders forgot first, because it went without saying. (pp. 123–24)

Part of the point of a philosophical society was this very seclusion from reality. Men from various walks of life—clergymen, officers, bankers—could forget their daily concerns and normal social identities to converse as equals in an imaginary world of “free thought”: free, that is, from attachments, obligations, responsibilities, and any possibility of failure.

In the years leading up to the Revolution, countless such organizations vied for followers and influence: Amis Réunis, Philalèthes, Chevaliers Bienfaisants, Amis de la Verité, several species of Freemasons, academies, literary and patriotic societies, schools, cultural associations and even agricultural societies—all barely dissimulating the same utopian political spirit (“philosophy”) behind official pretenses of knowledge, charity, or pleasure. They “were all more or less connected to one another and associated with those in Paris. Constant debates, elections, delegations, correspondence, and intrigue took place in their midst, and a veritable public life developed through them” (p. 124).

Because of the speculative character of the whole enterprise, the philosophes’ ideas could not be verified through action. Consequently, the societies developed criteria of their own, independent of the standards of validity that applied in the world outside:

Whereas in the real world the arbiter of any notion is practical testing and its goal what it actually achieves, in this world the arbiter is the opinion of others and its aim their approval. That is real which others see, that true which they say, that good of which they approve. Thus the natural order is reversed: opinion here is the cause and not, as in real life, the effect. (p. 39)

Many matters of deepest concern to ordinary men naturally got left out of discussion: “You know how difficult it is in mere conversation to mention faith or feeling,” remarks Cochin (p. 40; cf. p. 145). The long chains of reasoning at once complex and systematic which mark genuine philosophy—and are produced by the stubborn and usually solitary labors of exceptional men—also have no chance of success in a society of philosophes (p. 143). Instead, a premium gets placed on what can be easily expressed and communicated, which produces a lowest-common-denominator effect (p. 141).

The philosophes made a virtue of viewing the world surrounding them objectively and disinterestedly. Cochin finds an important clue to this mentality in a stock character of eighteenth-century literature: the “ingenuous man.” Montesquieu invented him as a vehicle for satire in the Persian Letters: an emissary from the King of Persia sending witty letters home describing the queer customs of Frenchmen. The idea caught on and eventually became a new ideal for every enlightened mind to aspire to. Cochin calls it “philosophical savagery”:

Imagine an eighteenth-century Frenchman who possesses all the material attainments of the civilization of his time—cultivation, education, knowledge, and taste—but without any of the real well-springs, the instincts and beliefs that have created and breathed life into all this, that have given their reason for these customs and their use for these resources. Drop him into this world of which he possesses everything except the essential, the spirit, and he will see and know everything but understand nothing. Everything shocks him. Everything appears illogical and ridiculous to him. It is even by this incomprehension that intelligence is measured among savages. (p. 43; cf. p. 148)

In other words, the eighteenth-century philosophes were the original “deracinated intellectuals.” They rejected as “superstitions” and “prejudices” the core beliefs and practices of the surrounding society, the end result of a long process of refining and testing by men through countless generations of practical endeavor. In effect, they created in France what a contributor to this journal has termed a “culture of critique”—an intellectual milieu marked by hostility to the life of the nation in which its participants were living. (It would be difficult, however, to argue a significant sociobiological basis in the French version.)

This gradual withdrawal from the real world is what historians refer to as the development of the Enlightenment. Cochin calls it an “automatic purging” or “fermentation.” It is not a rational progression like the stages in an argument, however much the philosophes may have spoken of their devotion to “Reason”; it is a mechanical process which consists of “eliminating the real world in the mind instead of reducing the unintelligible in the object” (p. 42). Each stage produces a more rarified doctrine and human type, just as each elevation on a mountain slope produces its own kind of vegetation. The end result is the world’s original “herd of independent minds,” a phenomenon which would have horrified even men such as Montesquieu and Voltaire who had characterized the first societies.

It is interesting to note that, like our own multiculturalists, many of the philosophes attempted to compensate for their estrangement from the living traditions of French civilization by a fascination with foreign laws and customs. Cochin aptly compares civilization to a living plant which slowly grows “in the bedrock of experience under the rays of faith,” and likens this sort of philosophe to a child mindlessly plucking the blossoms from every plant he comes across in order to decorate his own sandbox (pp. 43–44).

Accompanying the natural “fermentation” of enlightened doctrine, a process of selection also occurs in the membership of the societies. Certain men are simply more suited to the sort of empty talking that goes on there:

young men because of their age; men of law, letters or discourse because of their profession; the skeptics because of their convictions; the vain because of their temperament; the superficial because of their [poor] education. These people take to it and profit by it, for it leads to a career that the world here below does not offer them, a world in which their deficiencies become strengths. On the other hand, true, sincere minds with a penchant for the concrete, for efficacy rather than opinion, find themselves disoriented and gradually drift away. (pp. 40–41)

In a word, the glib drive out the wise.

The societies gradually acquired an openly partisan character: whoever agreed with their views, however stupid, was considered “enlightened.” By 1776, d’Alembert acknowledged this frankly, writing to Frederick the Great: “We are doing what we can to fill the vacant positions in the Académie française in the manner of the banquet of the master of the household in the Gospel: with the crippled and lame men of literature” (p. 35). Mediocrities such as Mably, Helvétius, d’Holbach, Condorcet, and Raynal, whose works Cochin calls “deserts of insipid prose” were accounted ornaments of their age. The philosophical societies functioned like hired clappers making a success of a bad play (p. 46).

On the other hand, all who did not belong to the “philosophical” party were subjected to a “dry terror”:

Prior to the bloody Terror of ’93, in the Republic of Letters there was, from 1765 to 1780, a dry terror of which the Encyclopedia was the Committee of Public Safety and d’Alembert was the Robespierre. It mowed down reputations as the other chopped off heads: its guillotine was defamation, “infamy” as it was then called: The term, originating with Voltaire [écrasez l’infâme!], was used in the provincial societies with legal precision. “To brand with infamy” was a well-defined operation consisting of investigation, discussion, judgment, and finally execution, which meant the public sentence of “contempt.” (p. 36; cf. p. 123)

Having said something of the thought and behavioral tendencies of the philosophes, let us turn to the manner in which their societies were constituted—which, as we have noted, Cochin considered the essential point. We shall find that they possess in effect two constitutions. One is the original and ostensible arrangement, which our author characterizes as “the democratic principle itself, in its principle and purity” (p. 137). But another pattern of governance gradually takes shape within them, hidden from most of the members themselves. This second, unacknowledged constitution is what allows the societies to operate effectively, even as it contradicts the original “democratic” ideal.

The ostensible form of the philosophical society is direct democracy. All members are free and equal; no one is forced to yield to anyone else; no one speaks on behalf of anyone else; everyone’s will is accomplished. Rousseau developed the principles of such a society in his Social Contract. He was less concerned with the glaringly obvious practical difficulties of such an arrangement than with the question of legitimacy. He did not ask: “How could perfect democracy function and endure in the real word?” but rather: “What must a society whose aim is the common good do to be founded lawfully?”

Accordingly, Rousseau spoke dismissively of the representative institutions of Britain, so admired by Montesquieu and Voltaire. The British, he said, are free only when casting their ballots; during the entire time between elections there are as enslaved as the subjects of the Great Turk. Sovereignty by its very nature cannot be delegated, he declared; the People, to whom it rightfully belongs, must exercise it both directly and continuously. From this notion of a free and egalitarian society acting in concert emerges a new conception of law not as a fixed principle but as the general will of the members at a given moment.

Rousseau explicitly states that the general will does not mean the will of the majority as determined by vote; voting he speaks of slightingly as an “empirical means.” The general will must be unanimous. If the merely “empirical” wills of men are in conflict, then the general will—their “true” will—must lie hidden somewhere. Where is it to be found? Who will determine what it is, and how?

At this critical point in the argument, where explicitness and clarity are most indispensable, Rousseau turns coy and vague: the general will is “in conformity with principles”; it “only exists virtually in the conscience or imagination of ‘free men,’ ‘patriots.’” Cochin calls this “the idea of a legitimate people—very similar to that of a legitimate prince. For the regime’s doctrinaires, the people is an ideal being” (p. 158).

There is a strand of thought about the French Revolution that might be called the “Ideas-Have-Consequences School.” It casts Rousseau in the role of a mastermind who elaborated all the ideas that less important men such as Robespierre merely carried out. Such is not Cochin’s position. In his view, the analogies between the speculations of the Social Contract and Revolutionary practice arise not from one having caused or inspired the other, but from both being based upon the philosophical societies.

Rousseau’s model, in other words, was neither Rome nor Sparta nor Geneva nor any phantom of his own “idyllic imagination”—he was describing, in a somewhat idealized form, the philosophical societies of his day. He treated these recent and unusual social formations as the archetype of all legitimate human association (cf. pp. 127, 155). As such a description—but not as a blueprint for the Terror—the Social Contract may be profitably read by students of the Revolution.

Indeed, if we look closely at the nature and purpose of a philosophical society, some of Rousseau’s most extravagant assertions become intelligible and even plausible. Consider unanimity, for example. The society is, let us recall, “an association founded to elicit through discussion [and] set by vote the common opinion of its members.” In other words, rather than coming together because they agree upon anything, the philosophes come together precisely in order to reach agreement, to resolve upon some common opinion. The society values union itself more highly than any objective principle of union. Hence, they might reasonably think of themselves as an organization free of disagreement.

Due to its unreal character, furthermore, a philosophical society is not torn by conflicts of interest. It demands no sacrifice—nor even effort—from its members. So they can all afford to be entirely “public spirited.” Corruption—the misuse of a public trust for private ends—is a constant danger in any real polity. But since the society’s speculations are not of this world, each philosophe is an “Incorruptible”:

One takes no personal interest in theory. So long as there is an ideal to define rather than a task to accomplish, personal interest, selfishness, is out of the question. [This accounts for] the democrats’ surprising faith in the virtue of mankind. Any philosophical society is a society of virtuous, generous people subordinating political motives to the general good. We have turned our back on the real world. But ignoring the world does not mean conquering it. (p. 155)

(This pattern of thinking explains why leftists even today are wont to contrast their own “idealism” with the “selfish” activities of businessmen guided by the profit motive.)

We have already mentioned that the more glib or assiduous attendees of a philosophical society naturally begin exercising an informal ascendancy over other members: in the course of time, this evolves into a standing but unacknowledged system of oligarchic governance:

Out of one hundred registered members, fewer than five are active, and these are the masters of the society. [This group] is composed of the most enthusiastic and least scrupulous members. They are the ones who choose the new members, appoint the board of directors, make the motions, guide the voting. Every time the society meets, these people have met in the morning, contacted their friends, established their plan, given their orders, stirred up the unenthusiastic, brought pressure to bear upon the reticent. They have subdued the board, removed the troublemakers, set the agenda and the date. Of course, discussion is free, but the risk in this freedom minimal and the “sovereign’s” opposition little to be feared. The “general will” is free—like a locomotive on its tracks. (pp. 172–73)

Cochin draws here upon James Bryce’s American Commonwealth and Moisey Ostrogorski’s Democracy and the Organization of Political Parties. Bryce and Ostrogorski studied the workings of Anglo-American political machines such as New York’s Tammany Hall and Joseph Chamberlain’s Birmingham Caucus. Cochin considered such organizations (plausibly, from what I can tell) to be authentic descendants of the French philosophical and revolutionary societies. He thought it possible, with due circumspection, to apply insights gained from studying these later political machines to previously misunderstand aspects of the Revolution.

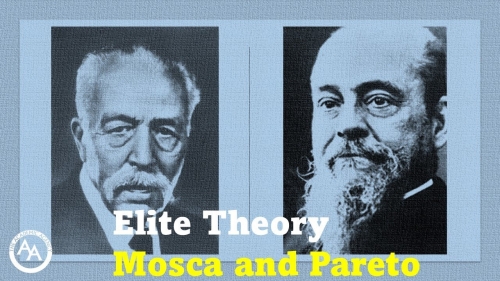

One book with which Cochin seems unfortunately not to have been familiar is Robert Michels’ Political Parties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democracy, published in French translation only in 1914. But he anticipated rather fully Michels’ “iron law of oligarchy,” writing, for example, that “every egalitarian society fatally finds itself, after a certain amount of time, in the hands of a few men; this is just the way things are” (p. 174). Cochin was working independently toward conclusions notably similar to those of Michels and Gaetano Mosca, the pioneering Italian political sociologists whom James Burnham called “the Machiavellians.” The significance of his work extends far beyond that of its immediate subject, the French Revolution.

The essential operation of a democratic political machine consists of just two steps, continually repeated: the preliminary decision and the establishment of conformity.

First, the ringleaders at the center decide upon some measure. They prompt the next innermost circles, whose members pass the message along until it reaches the machine’s operatives in the outermost local societies made up of poorly informed people. All this takes place unofficially and in secrecy (p. 179).

Then the local operatives ingenuously “make a motion” in their societies, which is really the ringleaders’ proposal without a word changed. The motion passes—principally through the passivity (Cochin writes “inertia”) of the average member. The local society’s resolution, which is now binding upon all its members, is with great fanfare transmitted back towards the center.

The central society is deluged with identical “resolutions” from dozens of local societies simultaneously. It hastens to endorse and ratify these as “the will of the nation.” The original measure now becomes binding upon everyone, though the majority of members have no idea what has taken place. Although really a kind of political ventriloquism by the ringleaders, the public opinion thus orchestrated “reveals a continuity, cohesion and vigor that stuns the enemies of Jacobinism” (p. 180).

In his study of the beginnings of the Revolution in Brittany, Cochin found sudden reversals of popular opinion which the likes of Monsieur Aulard would have taken at face value, but which become intelligible once viewed in the light of the democratic mechanism:

On All Saints’ Day, 1789, a pamphlet naïvely declared that not a single inhabitant imagined doing away with the privileged orders and obtaining individual suffrage, but by Christmas hundreds of the common people’s petitions were clamoring for individual suffrage or death. What was the origin of this sudden discovery that people had been living in shame and slavery for the past thousand years? Why was there this imperious, immediate need for a reform which could not wait a minute longer?

Such abrupt reversals are sufficient in themselves to detect the operation of a machine. (p. 179)

The basic democratic two-step is supplemented with a bevy of techniques for confusing the mass of voters, discouraging them from organizing opposition, and increasing their passivity and pliability: these techniques include constant voting about everything—trivial as well as important; voting late at night, by surprise, or in multiple polling places; extending the suffrage to everyone: foreigners, women, criminals; and voting by acclamation to submerge independent voices (pp. 182–83). If all else fails, troublemakers can be purged from the society by ballot:

This regime is partial to people with all sorts of defects, failures, malcontents, the dregs of humanity, anyone who cares for nothing and finds his place nowhere. There must not be religious people among the voters, for faith makes one conscious and independent. [The ideal citizen lacks] any feeling that might oppose the machine’s suggestions; hence also the preference for foreigners, the haste in naturalizing them. (pp. 186–87)

(I bite my lip not to get lost in the contemporary applications.)

The extraordinary point of Cochin’s account is that none of these basic techniques were pioneered by the revolutionaries themselves; they had all been developed in the philosophical societies before the Revolution began. The Freemasons, for example, had a term for their style of internal governance: the “Royal Art.” “Study the social crisis from which the Grand Lodge [of Paris Freemasons] was born between 1773 and 1780,” says Cochin, “and you will find the whole mechanism of a Revolutionary purge” (p. 61).

Secrecy is essential to the functioning of this system; the ordinary members remain “free,” meaning they do not consciously obey any authority, but order and unity are maintained by a combination of secret manipulation and passivity. Cochin relates “with what energy the Grand Lodge refused to register its Bulletin with the National Library” (p. 176). And, of course, the Freemasons and similar organizations made great ado over refusing to divulge the precise nature of their activities to outsiders, with initiates binding themselves by terrifying oaths to guard the sacred trust committed to them. Much of these societies’ appeal lay precisely in the natural pleasure men feel at being “in” on a secret of any sort.

In order to clarify Cochin’s ideas, it might be useful to contrast them at this point with those of the Abbé Barruel, especially as they have been confounded by superficial or dishonest leftist commentators (“No need to read that reactionary Cochin! He only rehashes Barruel’s conspiracy thesis”).

Father Barruel was a French Jesuit living in exile in London when he published his Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism in 1797. He inferred from the notorious secretiveness of the Freemasons and similar groups that they must have been plotting for many years the horrors revealed to common sight after 1789—conspiring to abolish monarchy, religion, social hierarchy, and property in order to hold sway over the ruins of Christendom.

Cochin was undoubtedly thinking of Barruel and his followers when he laments that

thus far, in the lives of these societies, people have only sought the melodrama—rites, mystery, disguises, plots—which means they have strayed into a labyrinth of obscure anecdotes, to the detriment of the true history, which is very clear. Indeed the interest in the phenomenon in question is not in the Masonic bric-a-brac, but in the fact that in the bosom of the nation the Masons instituted a small state governed by its own rules. (p. 137)

For our author, let us recall, a société de pensée such as the Masonic order has inherent constraints independent of the desires or intentions of the members. Secrecy—of the ringleaders in relation to the common members, and of the membership to outsiders—is one of these necessary aspects of its functioning, not a way of concealing criminal intentions. In other words, the Masons were not consciously “plotting” the Terror of ’93 years in advance; the Terror was, however, an unintended but natural outcome of the attempt to apply a version of the Mason’s “Royal Art” to the government of an entire nation.

Moreover, writes Cochin, the peculiar fanaticism and force of the Revolution cannot be explained by a conspiracy theory. Authors like Barruel would reduce the Revolution to “a vast looting operation”:

But how can this enthusiasm, this profusion of noble words, these bursts of generosity or fits of rage be only lies and play-acting? Could the Revolutionary party be reduced to an enormous plot in which each person would only be thinking [and] acting for himself while accepting an iron discipline? Personal interest has neither such perseverance nor such abnegation. Throughout history there have been schemers and egoists, but there have only been revolutionaries for the past one hundred fifty years. (pp. 121–22)

And finally, let us note, Cochin included academic and literary Societies, cultural associations, and schools as sociétés de pensée. Many of these organizations did not even make the outward fuss over secrecy and initiation that the Masons did.

By his own admission, Cochin has nothing to tell us about the causes of the Revolution’s outbreak:

I am not saying that in the movement of 1789 there were not real causes—[e.g.,] a bad fiscal regime that exacted very little, but in the most irritating and unfair manner—I am just saying these real causes are not my subject. Moreover, though they may have contributed to the Revolution of 1789, they did not contribute to the Revolutions of August 10 [1792, abolition of the monarchy] or May 31 [1793, purge of the Girondins]. (p. 125)

With these words, he turns his back upon the entire Marxist “class struggle” approach to understanding the Revolution, which was the fundamental presupposition of much twentieth-century research.

The true beginning of the Revolution on Cochin’s account was the announcement in August 1788 that the Estates General would be convoked for May 1789, for this was the occasion when the men of the societies first sprang into action to direct a real political undertaking. With his collaborator in archival work, Charpentier, he conducted extensive research into this early stage of the Revolution in Brittany and Burgundy, trying to explain not why it took place but how it developed. This material is omitted from the present volume of translations; I shall cite instead from Furet’s summary and discussion in Interpreting the French Revolution:

In Burgundy in the autumn of 1788, political activity was exclusively engineered by a small group of men in Dijon who drafted a “patriotic” platform calling for the doubling of the Third Estate, voting by head, and the exclusion of ennobled commoners and seigneurial dues collectors from the assemblies of the Third Estate. Their next step was the systematic takeover of the town’s corporate bodies. First came the avocats’ corporation where the group’s cronies were most numerous; then the example of that group was used to win over other wavering or apathetic groups: the lower echelons of the magistrature, the physicians, the trade guilds. Finally the town hall capitulated, thanks to one of the aldermen and pressure from a group of “zealous citizens.” In the end, the platform appeared as the freely expressed will of the Third Estate of Dijon. Promoted by the usurped authority of the Dijon town council, it then reached the other towns of the province.[2]

. . . where the same comedy was acted out, only with less trouble since the platform now apparently enjoyed the endorsement of the provincial capital. Cochin calls this the “snowballing method” (p. 84).

An opposition did form in early December: a group of nineteen noblemen which grew to fifty. But the remarkable fact is that the opponents of the egalitarian platform made no use of the traditional institutions or assemblies of the nobility; these were simply forgotten or viewed as irrelevant. Instead, the nobles patterned their procedures on those of the rival group: they thought and acted as the “right wing” of the revolutionary party itself. Both groups submitted in advance to arbitration by democratic legitimacy. The episode, therefore, marked not a parting of the ways between the supporters of the old regime and adherents of the new one, but the first of the revolutionary purges. Playing by its enemies’ rules, the opposition was defeated by mid-December.[3]

In Brittany an analogous split occurred in September and October rather than December. The traditional corporate bodies and the philosophical societies involved had different names. The final purge of the nobles was not carried out until January 1789. The storyline, however, was essentially the same. [4] La Révolution n’a pas de patrie (p. 131).

The regulations for elections to the Estates General were finally announced on January 24, 1789. As we shall see, they provided the perfect field of action for the societies’ machinations.

The Estates General of France originated in the fourteenth century, and were summoned by the King rather than elected. The first two estates consisted of the most important ecclesiastical and lay lords of the realm, respectively. The third estate consisted not of the “commoners,” as usually thought, but of the citizens of certain privileged towns which enjoyed a direct relation with the King through a royal charter (i.e., they were not under the authority of any feudal lord). The selection of notables from this estate may have involved election, although based upon a very restricted franchise.

In the Estates General of those days, the King was addressing

the nation with its established order and framework, with its various hierarchies, its natural subdivisions, its current leaders, whatever the nature or origin of their authority. The king acknowledged in the nation an active, positive role that our democracies would not think of granting to the electoral masses. This nation was capable of initiative. Representatives with a general mandate—professional politicians serving as necessary intermediaries between the King and the nation—were unheard of. (pp. 97–98)

Cochin opposes to this older “French conception” the “English and parliamentary conception of a people of electors”:

A people made up of electors is no longer capable of initiative; at most, it is capable of assent. It can choose between two or three platforms, two or three candidates, but it can no longer draft proposals or appoint men. Professional politicians must present the people with proposals and men. This is the role of parties, indispensable in such a regime. (p. 98)

In 1789, the deputies were elected to the States General on a nearly universal franchise, but—in accordance with the older French tradition—parties and formal candidacies were forbidden: “a candidate would have been called a schemer, and a party a cabal” (p. 99).

The result was that the “electors were placed not in a situation of freedom, but in a void”:

The effect was marvelous: imagine several hundred peasants, unknown to each other, some having traveled twenty or thirty leagues, confined in the nave of a church, and requested to draft a paper on the reform of the realm within the week, and to appoint twenty or thirty deputies. There were ludicrous incidents: at Nantes, for example, where the peasants demanded the names of the assembly’s members be printed. Most could not have cited ten of them, and they had to appoint twenty-five deputies.

Now, what actually happened? Everywhere the job was accomplished with ease. The lists of grievances were drafted and the deputies appointed as if by enchantment. This was because alongside the real people who could not respond there was another people who spoke and appointed for them. (p. 100)

These were, of course, the men of the societies. They exploited the natural confusion and ignorance of the electorate to the hilt to obtain delegates according to their wishes. “From the start, the societies ran the electoral assemblies, scheming and meddling on the pretext of excluding traitors that they were the only ones to designate” (p. 153).

“Excluding”—that is the key word:

The society was not in a position to have its men nominated directly [parties being forbidden], so it had only one choice: have all the other candidates excluded. The people, it was said, had born enemies that they must not take as their defenders. These were the men who lost by the people’s enfranchisement, i.e., the privileged men first, but also the ones who worked for them: officers of justice, tax collectors, officials of any sort. (p. 104)

This raised an outcry, for it would have eliminated nearly everyone competent to represent the Third Estate. In fact, the strict application of the principle would have excluded most members of the societies themselves. But pretexts were found for excepting them from the exclusion: the member’s “patriotism” and “virtue” was vouched for by the societies, which “could afford to do this without being accused of partiality, for no one on the outside would have the desire, or even the means, to protest” (p. 104)—the effect of mass inertia, once again.

Having established the “social mechanism” of the revolution, Cochin did not do any detailed research on the events of the following four years (May 1789–June 1793), full of interest as these are for the narrative historian. Purge succeeded purge: Monarchiens, Feuillants, Girondins. Yet none of the actors seemed to grasp what was going on:

Was there a single revolutionary team that did not attempt to halt this force, after using it against the preceding team, and that did not at that very moment find itself “purged” automatically? It was always the same naïve amazement when the tidal wave reached them: “But it’s with me that the good Revolution stops! The people, that’s me! Freedom here, anarchy beyond!” (p. 57)

During this period, a series of elective assemblies crowned the official representative government of France: first the Constituent Assembly, then the Legislative Assembly, and finally the Convention. Hovering about them and partly overlapping with their membership were various private and exclusive clubs, a continuation of the pre-Revolutionary philosophical societies. Through a gradual process of gaining the affiliation of provincial societies, killing off rivals in the capital, and purging itself and its daughters, one of these revolutionary clubs acquired by June 1793 an unrivalled dominance. Modestly formed in 1789 as the Breton Circle, later renamed the Friends of the Constitution, it finally established its headquarters in a disused Jacobin Convent and became known as the Jacobin Club:

Opposite the Convention, the representative regime of popular sovereignty, thus arises the amorphous regime of the sovereign people, acting and governing on its own. “The sovereign is directly in the popular societies,” say the Jacobins. This is where the sovereign people reside, speak, and act. The people in the street will only be solicited for the hard jobs and the executions.

[The popular societies] functioned continuously, ceaselessly watching and correcting the legal authorities. Later they added surveillance committees to each assembly. The Jacobins thoroughly lectured, browbeat, and purged the Convention in the name of the sovereign people, until it finally adjourned the Convention’s power. (p. 153)

Incredibly, to the very end of the Terror, the Jacobins had no legal standing; they remained officially a private club. “The Jacobin Society at the height of its power in the spring of 1794, when it was directing the Convention and governing France, had only one fear: that it would be ‘incorporated’—that it would be ‘acknowledged’ to have authority” (p. 176). There is nothing the strict democrat fears more than the responsibility associated with public authority.

The Jacobins were proud that they did not represent anyone. Their principle was direct democracy, and their operative assumption was that they were “the people.” “I am not the people’s defender,” said Robespierre; “I am a member of the people; I have never been anything else” (p. 57; cf. p. 154). He expressed bafflement when he found himself, like any powerful man, besieged by petitioners.

Of course, such “direct democracy” involves a social fiction obvious to outsiders. To the adherent “the word people means the ‘hard core’ minority, freedom means the minority’s tyranny, equality its privileges, and truth its opinion,” explains our author; “it is even in this reversal of the meaning of words that the adherent’s initiation consists” (p. 138).

But by the summer of 1793 and for the following twelve months, the Jacobins had the power to make it stick. Indeed, theirs was the most stable government France had during the entire revolutionary decade. It amounted to a second Revolution, as momentous as that of 1789. The purge of the Girondins (May 31–June 2) cleared the way for it, but the key act which constituted the new regime, in Cochin’s view, was the levée en masse of August 23, 1793:

[This decree] made all French citizens, body and soul, subject to standing requisition. This was the essential act of which the Terror’s laws would merely be the development, and the revolutionary government the means. Serfs under the King in ’89, legally emancipated in ’91, the people become the masters in ’93. In governing themselves, they do away with the public freedoms that were merely guarantees for them to use against those who governed them. Hence the right to vote is suspended, since the people reign; the right to defend oneself, since the people judge; the freedom of the press, since the people write; and the freedom of expression, since the people speak. (p. 77)

An absurd series of unenforceable economic decrees began pouring out of Paris—price ceilings, requisitions, and so forth. But then, mirabile dictu, it turned out that the decrees needed no enforcement by the center:

Every violation of these laws not only benefits the guilty party but burdens the innocent one. When a price ceiling is poorly applied in one district and products are sold more expensively, provisions pour in from neighboring districts, where shortages increase accordingly. It is the same for general requisitions, censuses, distributions: fraud in one place increases the burden for another. The nature of things makes every citizen the natural enemy and overseer of his neighbor. All these laws have the same characteristic: binding the citizens materially to one another, the laws divide them morally.

Now public force to uphold the law becomes superfluous. This is because every district, panic-stricken by famine, organizes its own raids on its neighbors in order to enforce the laws on provisions; the government has nothing to do but adopt a laissez-faire attitude. By March 1794 the Committee of Public Safety even starts to have one district’s grain inventoried by another.

This peculiar power, pitting one village against another, one district against another, maintained through universal division the unity that the old order founded on the union of everyone: universal hatred has its equilibrium as love has its harmony. (pp. 230–32; cf. p. 91)

The societies were, indeed, never more numerous, nor better attended, than during this period. People sought refuge in them as the only places they could be free from arbitrary arrest or requisitioning (p. 80; cf. p. 227). But the true believers were made uneasy rather than pleased by this development. On February 5, 1794, Robespierre gave his notorious speech on Virtue, declaring: “Virtue is in the minority on earth.” In effect, he was acknowledging that “the people” were really only a tiny fraction of the nation. During the months that ensued:

there was no talk in the Societies but of purges and exclusions. Then it was that the mother society, imitated as usual by most of her offspring, refused the affiliation of societies founded since May 31. Jacobin nobility became exclusive; Jacobin piety went from external mission to internal effort on itself. At that time it was agreed that a society of many members could not be a zealous society. The agents from Tournan sent to purge the club of Ozouer-la-Ferrière made no other reproach: the club members were too numerous for the club to be pure. (p. 56)

Couthon wrote from Lyon requesting “40 good, wise, honest republicans, a colony of patriots in this foreign land where patriots are in such an appalling minority.” Similar supplications came from Marseilles, Grenoble, Besançon; from Troy, where there were less than twenty patriots; and from Strasbourg, where there were said to be fewer than four—contending against 6,000 aristocrats!

The majority of men, remaining outside the charmed circle of revolutionary virtue, were:

“monsters,” “ferocious beasts seeking to devour the human race.” “Strike without mercy, citizen,” the president of the Jacobins tells a young soldier, “at anything that is related to the monarchy. Don’t lay down your gun until all our enemies are dead—this is humanitarian advice.” “It is less a question of punishing them than of annihilating them,” says Couthon. “None must be deported; [they] must be destroyed,” says Collot. General Turreau in the Vendée gave the order “to bayonet men, women, and children and burn and set fire to everything.” (p. 100)

Mass shootings and drownings continued for months, especially in places such as the Vendée which had previously revolted. Foreigners sometimes had to be used: “Carrier had Germans do the drowning. They were not disturbed by the moral bonds that would have stopped a fellow countryman” (p. 187).

Why did this revolutionary regime come to an end? Cochin does not tell us; he limits himself to the banal observation that “being unnatural, it could not last” (p. 230). His death in 1916 saved him from having to consider the counterexample of Soviet Russia. Taking the Jacobins consciously as a model, Lenin created a conspiratorial party which seized power and carried out deliberately the sorts of measures Cochin ascribes to the impersonal workings of the “social mechanism.” Collective responsibility, mutual surveillance and denunciation, the playing off of nationalities against one another—all were studiously imitated by the Bolsheviks. For the people of Russia, the Terror lasted at least thirty-five years, until the death of Stalin.

Cochin’s analysis raises difficult questions of moral judgment, which he does not try to evade. If revolutionary massacres were really the consequence of a “social mechanism,” can their perpetrators be judged by the standards which apply in ordinary criminal cases? Cochin seems to think not:

“I had orders,” Fouquier kept replying to each new accusation. “I was the ax,” said another; “does one punish an ax?” Poor, frightened devils, they quibbled, haggled, denounced their brothers; and when finally cornered and overwhelmed, they murmured “But I was not the only one! Why me?” That was the helpless cry of the unmasked Jacobin, and he was quite right, for a member of the societies was never the only one: over him hovered the collective force. With the new regime men vanish, and there opens in morality itself the era of unconscious forces and human mechanics. (p. 58)

Under the social regime, man’s moral capacities get “socialized” in the same way as his thought, action, and property. “Those who know the machine know there exist mitigating circumstances, unknown to ordinary life, and the popular curse that weighed on the last Jacobins’ old age may be as unfair as the enthusiasm that had acclaimed their elders,” he says (p. 210), and correctly points out that many of the former Terrorists became harmless civil servants under the Empire.

It will certainly be an unpalatable conclusion for many readers. I cannot help recalling in this connection the popular outrage which greeted Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem back in the 1960s, with its similar observations.

But if considering the social alienation of moral conscience permits the revolutionaries to appear less evil than some of the acts they performed, it also leaves them more contemptible. “We are far from narratives like Plutarch’s,” Cochin observes (p. 58); “Shakespeare would have found nothing to inspire him, despite the dramatic appearance of the situations” (p. 211).

Not one [of the Jacobins] had the courage to look [their judges] in the eye and say “Well, yes, I robbed, I tortured and I killed lawlessly, recklessly, mercilessly for an idea I consider right. I regret nothing; I take nothing back; I deny nothing. Do as you like with me.” Not one spoke thus—because not one possessed the positive side of fanaticism: faith. (p. 113)

Cochin’s interpretive labors deserve the attention of a wider audience than specialists in the history of the French Revolution. The possible application of his analysis to subsequent groups and events is great indeed, although the possibility of their misapplication is perhaps just as great. The most important case is surely Russia. Richard Pipes has noted, making explicit reference to Cochin, that Russian radicalism arose in a political and social situation similar in important respects to France of the ancien régime. On the other hand, the Russian case was no mere product of social “mechanics.” The Russian radicals consciously modeled themselves on their French predecessors. Pipes even shows how the Russian revolutionaries relied too heavily on the French example to teach them how a revolution is “supposed to” develop, blinding themselves to the situation around them. In any case, although Marxism officially considered the French Revolution a “bourgeois” prelude to the final “proletarian” revolution, Russian radicals did acknowledge that there was little in which the Jacobins had not anticipated them. Lenin considered Robespierre a Bolshevik avant la lettre.

The rise of the “Academic Left” is another phenomenon worth comparing to the “development of the enlightenment” in the French salons. The sheltered environment of our oversubsidized university system is a marvelous incubator for the same sort of utopian radicalism and cheap moral posturing.

Or consider the feminist “Consciousness Raising” sessions of the 1970’s. Women’s “personal constructs” (dissatisfaction with their husbands, feelings of being treated unfairly, etc.) were said to be “validated by the group,” i.e., came to be considered true when they met with agreement from other members, however outlandish they might sound to outsiders. “It is when a group’s ideas are strongly at variance with those in the wider society,” writes one enthusiast, “that group validation of constructs is likely to be most important.”[5] Cochin explained with reference to the sociétés de pensée exactly the sort of thing going on here.

Any serious attempt to extend and apply Cochin’s ideas will, however, have to face squarely one matter on which his own statements are confused or even contradictory.

Cochin sometimes speaks as if all the ideas of the Enlightenment follow from the mere form of the société de pensée, and hence should be found wherever they are found. He writes, for example, “Free thought is the same in Paris as in Peking, in 1750 as in 1914” (p. 127). Now, this is already questionable. It would be more plausible to say that the various competing doctrines of radicalism share a family resemblance, especially if one concentrates on their negative aspects such as the rejection of traditional “prejudices.”

But in other passages Cochin allows that sociétés de pensée are compatible with entirely different kinds of content. In one place (p. 62) he even speaks of “the royalist societies of 1815” as coming under his definition! Stendhal offers a memorable fictional portrayal of such a group in Le rouge et le noir, part II, chs. xxi–xxiii; Cochin himself refers to the Mémoires of Aimée de Coigny, and may have had the Waterside Conspiracy in mind. It would not be at all surprising if such groups imitated some of the practices of their enemies.

But what are we to say when Cochin cites the example of the Company of the Blessed Sacrament? This organization was active in France between the 1630s and 1660s, long before the “Age of Enlightenment.” It had collectivist tendencies, such as the practice of “fraternal correction,” which it justified in terms of Christian humility: the need to combat individual pride and amour-propre. It also exhibited a moderate degree of egalitarianism; within the Company, social rank was effaced, and one Prince of the Blood participated as an ordinary member. Secrecy was said to be the “soul of the Company.” One of its activities was the policing of behavior through a network of informants, low-cut evening dresses and the sale of meat during lent being among its special targets. Some fifty provincial branches accepted the direction of the Paris headquarters. The Company operated independently of the King, and opponents referred to it as the cabale des devots. Louis XIV naturally became suspicious of such an organization, and officially ordered it shut down in 1666.

Was this expression of counter-reformational Catholic piety a société de pensée? Were its members “God’s Jacobins,” or its campaign against immodest dress a “holy terror”? Cochin does not finally tell us. A clear typology of sociétés de pensée would seem to be necessary before his analysis of the philosophes could be extended with any confidence. But the more historical studies advance, the more difficult this task will likely become. Such is the nature of man, and of history.

Notes

[1] François Furet, Interpreting the French Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 173.

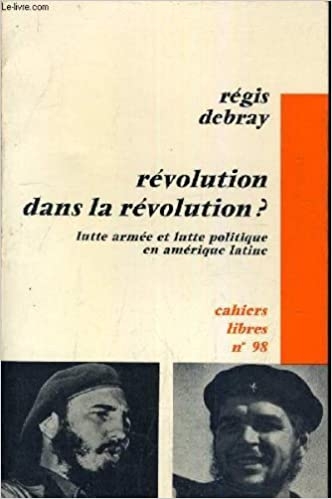

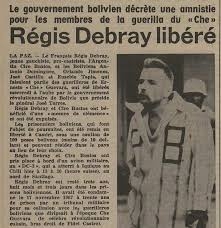

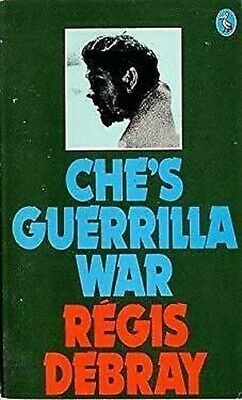

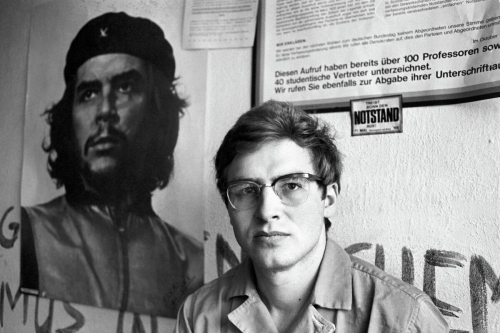

En 1967, l’éditeur des milieux gauchistes, François Maspero, réalise un beau coup éditorial. Il sort Révolution dans la révolution ? d’un agrégé de philosophie de 26 ans, Régis Debray qui vit depuis plusieurs mois à La Havane.

En 1967, l’éditeur des milieux gauchistes, François Maspero, réalise un beau coup éditorial. Il sort Révolution dans la révolution ? d’un agrégé de philosophie de 26 ans, Régis Debray qui vit depuis plusieurs mois à La Havane.

Révolution dans la révolution ? Expose ainsi une vision exigeante, spartiate même, du militantisme. L’esprit d’abnégation, de service et de sacrifice parcourt tout l’ouvrage. Rejoindre une guérilla dans une jungle hostile ou au cœur d’une montagne inhospitalière secoue, bouleverse et remue les tripes du vieil homme. « On dit bien que nous baignons dans le social : les bains prolongés amollissent. Rien de tel que d’en sortir pour se rendre compte à quel point ces couveuses tièdes infantilisent et embourgeoisent. Les premiers temps dans la montagne, reclus dans la forêt dite vierge, la vie est tout simplement un combat de chaque jour, dans ses moindres détails – et d’abord un combat du guérillero contre lui-même, pour surmonter ses anciennes habitudes, les marques laissées par la couveuse dans son corps, sa faiblesse. L’ennemi à vaincre, dans les premiers mois, c’est lui-même, et on ne sort pas toujours vainqueur de ce combat-là : beaucoup abandonnent, désertent ou redescendent volontairement vers la ville, assumer d’autres tâches (pp. 71 – 72). » Dans un foyer guérillero, on y apprend aussi la fraternité, la solidarité et la communauté. « La première loi d’une guérilla, c’est qu’on n’y survit pas seul. L’intérêt du groupe est l’intérêt de chacun, et vice-versa. Vivre et vaincre, c’est vivre et vaincre tous ensemble. Qu’un seul combattant traîne et reste en arrière de la colonne en marche, c’est toute la colonne qui est compromise, dans sa rapidité et sa sécurité. À l’arrière, il y a l’ennemi : impossible de laisser le compagnon en chemin, ni de le renvoyer. À tous donc, de se répartir sa charge, alléger son sac, ses cartouchières, et de l’entourer jusqu’au but. Dans ces conditions l’égoïsme de classe ne fait pas long feu (p. 119). » Cette approche est cohérente parce que « lutter pour un maximum d’efficacité, c’est lutter en toute occasion pour la réunion de la théorie et de la pratique, et non contre la théorie au nom de la pratique à tout prix (p. 9, souligné par l’auteur) ». Ce livre manifeste une indéniable aspiration soldatique.

Révolution dans la révolution ? Expose ainsi une vision exigeante, spartiate même, du militantisme. L’esprit d’abnégation, de service et de sacrifice parcourt tout l’ouvrage. Rejoindre une guérilla dans une jungle hostile ou au cœur d’une montagne inhospitalière secoue, bouleverse et remue les tripes du vieil homme. « On dit bien que nous baignons dans le social : les bains prolongés amollissent. Rien de tel que d’en sortir pour se rendre compte à quel point ces couveuses tièdes infantilisent et embourgeoisent. Les premiers temps dans la montagne, reclus dans la forêt dite vierge, la vie est tout simplement un combat de chaque jour, dans ses moindres détails – et d’abord un combat du guérillero contre lui-même, pour surmonter ses anciennes habitudes, les marques laissées par la couveuse dans son corps, sa faiblesse. L’ennemi à vaincre, dans les premiers mois, c’est lui-même, et on ne sort pas toujours vainqueur de ce combat-là : beaucoup abandonnent, désertent ou redescendent volontairement vers la ville, assumer d’autres tâches (pp. 71 – 72). » Dans un foyer guérillero, on y apprend aussi la fraternité, la solidarité et la communauté. « La première loi d’une guérilla, c’est qu’on n’y survit pas seul. L’intérêt du groupe est l’intérêt de chacun, et vice-versa. Vivre et vaincre, c’est vivre et vaincre tous ensemble. Qu’un seul combattant traîne et reste en arrière de la colonne en marche, c’est toute la colonne qui est compromise, dans sa rapidité et sa sécurité. À l’arrière, il y a l’ennemi : impossible de laisser le compagnon en chemin, ni de le renvoyer. À tous donc, de se répartir sa charge, alléger son sac, ses cartouchières, et de l’entourer jusqu’au but. Dans ces conditions l’égoïsme de classe ne fait pas long feu (p. 119). » Cette approche est cohérente parce que « lutter pour un maximum d’efficacité, c’est lutter en toute occasion pour la réunion de la théorie et de la pratique, et non contre la théorie au nom de la pratique à tout prix (p. 9, souligné par l’auteur) ». Ce livre manifeste une indéniable aspiration soldatique.  Régis Debray, et par-delà lui, rappelons-le, Fidel Castro, ne valide pas la démarche fixiste, routinière et stérile des héritiers de Léon Bronstein. « Dans certaines conditions, l’instance politique ne se sépare pas de l’instance militaire, elles forment un seul tout organique. Cette organisation, c’est celle de l’Armée populaire dont le noyau est l’armée guérillera. Le Parti d’avant-garde peut exister sous la forme propre du foyer guérillero. La guérilla est le Parti en gestation (pp. 113 – 114, souligné par l’auteur). » Dans l’espoir de l’emporter, « toute ligne militaire dépend d’une ligne politique qu’elle exprime (p. 21) » d’autant que « ce qui est décisif pour l’avenir, c’est l’ouverture de foyers militaires et non de “ foyers ” politiques (p. 129) ». Le foquisme se comprend comme une dynamique aux tactiques mouvantes adaptées à la réalité du terrain et aux circonstances du moment. Il désavoue en outre « l’économisme, c’est la défense exclusive des intérêts professionnels des travailleurs contre les empiétements du pouvoir patronal, à travers le syndicat; comme il est exclu d’attaquer le pouvoir politique des patrons, l’État bourgeois, cette défense accepte et avalise en fait ce qu’elle prétend combattre (p. 24, souligné par l’auteur) ». Il dénie tout sérieux à l’autodéfense. « De même que l’économisme nie le rôle du parti d’avant-garde, de même l’autodéfense nie le rôle du détachement armé, organiquement distinct de la population civile (p. 26). »

Régis Debray, et par-delà lui, rappelons-le, Fidel Castro, ne valide pas la démarche fixiste, routinière et stérile des héritiers de Léon Bronstein. « Dans certaines conditions, l’instance politique ne se sépare pas de l’instance militaire, elles forment un seul tout organique. Cette organisation, c’est celle de l’Armée populaire dont le noyau est l’armée guérillera. Le Parti d’avant-garde peut exister sous la forme propre du foyer guérillero. La guérilla est le Parti en gestation (pp. 113 – 114, souligné par l’auteur). » Dans l’espoir de l’emporter, « toute ligne militaire dépend d’une ligne politique qu’elle exprime (p. 21) » d’autant que « ce qui est décisif pour l’avenir, c’est l’ouverture de foyers militaires et non de “ foyers ” politiques (p. 129) ». Le foquisme se comprend comme une dynamique aux tactiques mouvantes adaptées à la réalité du terrain et aux circonstances du moment. Il désavoue en outre « l’économisme, c’est la défense exclusive des intérêts professionnels des travailleurs contre les empiétements du pouvoir patronal, à travers le syndicat; comme il est exclu d’attaquer le pouvoir politique des patrons, l’État bourgeois, cette défense accepte et avalise en fait ce qu’elle prétend combattre (p. 24, souligné par l’auteur) ». Il dénie tout sérieux à l’autodéfense. « De même que l’économisme nie le rôle du parti d’avant-garde, de même l’autodéfense nie le rôle du détachement armé, organiquement distinct de la population civile (p. 26). »

Révolution dans la révolution ? reste bien une œuvre à part dans l’abondante bibliographie du philosophe. Sa lecture à la fin des années 1970 dans les squats autonomes, organisés ou non, suscitera un engouement considérable, déclenchant chez certains l’intention d’importer en Europe et en France pré-mitterrandienne un activisme armé similaire (10). Bien que maintenant daté, ce manuel de guérilla peut à sa manière aider la véritable dissidence en cours à mieux investir les périphéries à partir de BAD disséminées dans toutes les campagnes pour mieux ensuite assécher les centres métropolitains de la bobocratie cosmopolite…

Révolution dans la révolution ? reste bien une œuvre à part dans l’abondante bibliographie du philosophe. Sa lecture à la fin des années 1970 dans les squats autonomes, organisés ou non, suscitera un engouement considérable, déclenchant chez certains l’intention d’importer en Europe et en France pré-mitterrandienne un activisme armé similaire (10). Bien que maintenant daté, ce manuel de guérilla peut à sa manière aider la véritable dissidence en cours à mieux investir les périphéries à partir de BAD disséminées dans toutes les campagnes pour mieux ensuite assécher les centres métropolitains de la bobocratie cosmopolite…

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

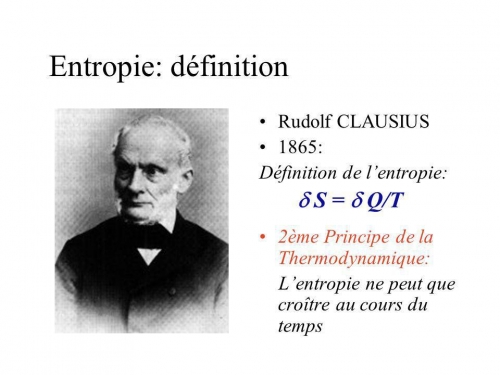

Lénine dans Matérialisme et empiriocriticisme s’insurgeait avec une véhémence de prêtre aigri contre Mach et Bogdanov, auxquels l’avenir donnera raison. Un « socialisme scientifique », aujourd’hui, ou, plus exactement, une « alternative politique scientifique », doit fusionner 1) la sévérité de Marx et d’Engels à l’égard des « utopismes » socialisants et anarchisants ne conduisant qu’à des fantaisies infécondes et 2) le regard de Mach et de Bogdanov sur la non-linéarité uni-vectorielle du temps, sur l’émergence toujours possible d’imprévisibilités, de probabilités non captables à l’avance, de ressac, d’entropie (même au sein de notre propre réseau associatif).

Lénine dans Matérialisme et empiriocriticisme s’insurgeait avec une véhémence de prêtre aigri contre Mach et Bogdanov, auxquels l’avenir donnera raison. Un « socialisme scientifique », aujourd’hui, ou, plus exactement, une « alternative politique scientifique », doit fusionner 1) la sévérité de Marx et d’Engels à l’égard des « utopismes » socialisants et anarchisants ne conduisant qu’à des fantaisies infécondes et 2) le regard de Mach et de Bogdanov sur la non-linéarité uni-vectorielle du temps, sur l’émergence toujours possible d’imprévisibilités, de probabilités non captables à l’avance, de ressac, d’entropie (même au sein de notre propre réseau associatif).

Mikhaïl Alexandrovitch n'était pas le seul représentant de la "nouvelle pensée révolutionnaire". Sa cousine, Catherine, n'était pas en reste. Selon ses souvenirs, dans sa jeunesse, la jeune fille était plutôt une "jeune fille innocente", mais à l'âge adulte, elle est devenue résolue et forte, une véritable manifestation de l'homme libre, comme Bakounine lui-même l'entendait. À force de persévérance, Catherine réussit à se faire engager comme sœur de miséricorde dans la ville assiégée de Sébastopol pendant la guerre de Crimée. "Je devais résister par tous les moyens et avec toute mon habileté au mal que divers fonctionnaires, fournisseurs, etc. infligeaient à nos malades dans les hôpitaux ; et je considérais que c'était mon devoir sacré de lutter et de résister", a déclaré plus tard Catherine pour décrire son véritable objectif. Son esprit rebelle de résistance à la bureaucratie, sa fermeté et sa persévérance ne sont pas passés inaperçus aux yeux de Nikolaï Pirogov : "Chaque jour et chaque nuit, on pouvait la trouver dans la salle d'opération, assistant aux opérations, alors que des bombes et des missiles traînaient autour d'elle. Elle faisait preuve d'une présence d'esprit difficilement compatible avec la nature d'une femme". Qu'est-ce que cela signifie ? Que Bakounine lui-même, mais aussi tous les membres de sa famille, n'étaient pas seulement de fortes personnalités, mais aussi des personnes qui n'avaient pas peur de s'affirmer, des personnes qui aimaient la liberté et la vérité. L'éducation et l'environnement ont beaucoup influencé le futur anarchiste et révolutionnaire.

Mikhaïl Alexandrovitch n'était pas le seul représentant de la "nouvelle pensée révolutionnaire". Sa cousine, Catherine, n'était pas en reste. Selon ses souvenirs, dans sa jeunesse, la jeune fille était plutôt une "jeune fille innocente", mais à l'âge adulte, elle est devenue résolue et forte, une véritable manifestation de l'homme libre, comme Bakounine lui-même l'entendait. À force de persévérance, Catherine réussit à se faire engager comme sœur de miséricorde dans la ville assiégée de Sébastopol pendant la guerre de Crimée. "Je devais résister par tous les moyens et avec toute mon habileté au mal que divers fonctionnaires, fournisseurs, etc. infligeaient à nos malades dans les hôpitaux ; et je considérais que c'était mon devoir sacré de lutter et de résister", a déclaré plus tard Catherine pour décrire son véritable objectif. Son esprit rebelle de résistance à la bureaucratie, sa fermeté et sa persévérance ne sont pas passés inaperçus aux yeux de Nikolaï Pirogov : "Chaque jour et chaque nuit, on pouvait la trouver dans la salle d'opération, assistant aux opérations, alors que des bombes et des missiles traînaient autour d'elle. Elle faisait preuve d'une présence d'esprit difficilement compatible avec la nature d'une femme". Qu'est-ce que cela signifie ? Que Bakounine lui-même, mais aussi tous les membres de sa famille, n'étaient pas seulement de fortes personnalités, mais aussi des personnes qui n'avaient pas peur de s'affirmer, des personnes qui aimaient la liberté et la vérité. L'éducation et l'environnement ont beaucoup influencé le futur anarchiste et révolutionnaire.

En 1868, Bakounine prépare un projet de "Fraternité internationale", dans lequel il formule les principes de base de l'anarchisme, qui impliquent "la destruction complète de tout État, de toute église, de toute institution religieuse, politique, bureaucratique, judiciaire, financière, policière, économique, universitaire et fiscale".

En 1868, Bakounine prépare un projet de "Fraternité internationale", dans lequel il formule les principes de base de l'anarchisme, qui impliquent "la destruction complète de tout État, de toute église, de toute institution religieuse, politique, bureaucratique, judiciaire, financière, policière, économique, universitaire et fiscale".

Like the French Revolution, the Russian is also marked by an alliance of philosophy with fanatical enthusiasm. And this fanaticism of the Lenin cult has found its intellectual fans up into the present—one thinks of the hypersensitive aesthetician Walter Benjamin, of the communist model poet Bert Brecht, of the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, then the student movement of ’68 and the present-day left. We owe the most extreme formulation of the cult to Ernst Bloch: “Ubi Lenin, ibi Jerusalem,” where Lenin is, there is salvation, the kingdom of freedom and eternal childhood in God. Ernst Nolte was thus right when he characterized Marxism as “the last faith in Europe.” And this faith was “organized” by Lenin.

Like the French Revolution, the Russian is also marked by an alliance of philosophy with fanatical enthusiasm. And this fanaticism of the Lenin cult has found its intellectual fans up into the present—one thinks of the hypersensitive aesthetician Walter Benjamin, of the communist model poet Bert Brecht, of the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, then the student movement of ’68 and the present-day left. We owe the most extreme formulation of the cult to Ernst Bloch: “Ubi Lenin, ibi Jerusalem,” where Lenin is, there is salvation, the kingdom of freedom and eternal childhood in God. Ernst Nolte was thus right when he characterized Marxism as “the last faith in Europe.” And this faith was “organized” by Lenin.