dimanche, 21 février 2010

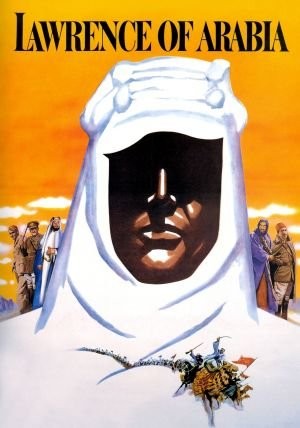

Lawrence of Arabia - the conflicted colonialist

Lawrence of Arabia - the conflicted colonialist

No wonder Lawrence is regarded with suspicion by the contemporary Arab world.

Lawrence was born in 1888 and went to Oxford. His boyish enthusiasm for medieval knights led him to walk across Syria and the Middle East in 1909, studying crusader castles for his university thesis, the fortresses that formed a chain of foreign, Christian domination over the local population.

Lawrence’s first job was as an archaeologist in a remote area of Syria, managing a huge native workforce for the Palestine Exploration Fund, an archaeological society whose survey of the region served as cover for British intelligence-gathering during the build-up to war with the Ottoman empire and Germany. Lawrence, with his excellent Arabic and local knowledge, drew up an ethnic map that detailed the many different tribal and religious areas.

During the First World War the Ottomans called for a jihad against the British. In response, Lawrence promised the Emir of Mecca, leader of the 1916 anti-Ottoman Arab revolt, support for a pan-Arab empire after the war if he launched a counter jihad against the Turks. It was this ability to “walk into the crowd” and harness Arab nationalism that marked him out as a first rate colonial soldier, according to leading British Arabist and former MI6 officer Sir Mark Allen.

Understanding the Ottomans’ difficulties in effectively patrolling the vast expanse of their desert territories, Lawrence used highly mobile Bedouin troops to ambush the enemy in a new form of guerilla warfare, targeting the Damascus-Medina railway, the sole supply line to the Ottoman garrison of Medina in Arabia. Using locals to do the bulk of the fighting, he went on to capture the strategically important Red Sea port of Aqaba, an exploit that shot him to fame and set the template for future special forces operations.

When British general Allenby marched as a modern crusader into Jerusalem in 1917, with Lawrence by his side as a Major, it was through the symbolically important Jaffa Gate, the ‘Conquerors’ Gate, and on foot rather than horseback because Christ had walked not ridden. This was for Lawrence “the supreme moment of his career.”

Yet when he learned of the secret British and French deal to divide the Arabian kingdom into two imperial possessions after the war, Lawrence wrote to his commanding officer: “We’ve asked them to fight on a lie, and I can’t stand it.”

Lawrence rushed his Arab fighters, who were loyal to the Emir and his son Faisal Hussein, to Damascus with the aim of taking it from the Ottomans before the British army arrived, gambling that once Faisal was established as king in this capital of the Arab world, it would be hard for Britain to topple him.

On October 1st 1918, wearing Arab clothes and riding in a Rolls Royce, Lawrence was cheered by a Damascus crowd of up to 150,000 people, having “inspired and ignited” their revolutionary fervour, according to Syrian historian Sami Moubayed. Faisal Hussein, a hero of the Arab revolt, followed two days later. But Lawrence had underestimated his own imperialism.

Under the infamous Sykes-Picot agreement the Middle East was divided “from the E of Acre to the last K of Kirkuk” in a straight, diagonal line across the map. France got Syria, Britain oil-rich Mosul and Palestine. It was a moment that “still rankles in the Arab psyche”, says Jordan’s foreign minister, a moment when “the western countries succeeded in … demolishing the hopes of the Arabs.” Bin Laden’s description of the deal as one which “dissected the Islamic world into fragments” underlines its contemporary resonance.

The Damascus meeting in 1918, at which Faisal was read out the Foreign Office telegram outlining the betrayal by France and Britain, marked “the start of the next 90 years of antagonism between the West and the Arab world. Lawrence left Damascus immediately, a failure, having delivered the Arabs to his British masters,” says Stewart.

Lawrence tried to break the Sykes-Picot agreement at Versailles in 1919, acting as Faisal’s adviser, but he merely became an embarrassment to the establishment. Defeated, he returned to England, where over a million people went to see a show at Covent Garden featuring ‘Lawrence of Arabia’.

When the British occupied Iraq, dropping bombs and gas to quell the insurgency, Lawrence wrote to the Times in 1920: “The people of England have been led into a trap in Iraq… it’s a disgrace to our imperial record”. Then in 1921, with the occupation failing, he was called on to advise Churchill, the Colonial Secretary, and Faisal was installed as a puppet ‘king’. The “last relic of Lawrence’s vision” lives on today in the shape of the pro-British kingdom of Jordan, still ruled by Faisal’s family.

What should we make of Lawrence today? Sami Moubayed describes him as “a British officer serving his nation’s interests. He was one of the many foreigners… who definitely does not deserve the homage you see nowadays.”

Stewart takes a different view, seeing Lawrence as a prophetic figure for our times. Stewart himself was deputy governor of two Iraqi provinces in 2003, where he initially “thought we could do some good”. He tried to “bring some semblance of order and prepare the country for independence,” but in the face of the insurgency he came to share Lawrence’s disillusionment with colonial rule.

Similarly disillusioned is Carne Ross, Britain’s former key negotiator at the UN, who resigned over the WMD issue. He tells Stewart: “I found it a deeply embittering experience… I think I was naïve about it…Ultimately my conclusion is one of deep skepticism of the state system and indeed of this place [the UN].”

These men’s disappointment is revealing. Stewart believes that “if generals and politicians now could see what Lawrence saw we would not be in the mess today”. He condemns the American misuse of Lawrence – troops shown David Lean’s swashbuckling film and made to read Lawrence’s 27-point guide to “try to… enter the Arab mindset”. He exposes the hollowness of General Patraeus’ new counter-insurgency manual enjoining troops “to work with local forces” by walking round Baghdad in the company of a US officer who speaks no Arabic and is ignorant of local politics.

Stewart, like Lawrence, rejects foreign occupation of the Middle East as unsustainable. “However much you do to overcome these cultural divides, in the end you don’t have the consent of the people; it’s not your country,” he says, echoing Lawrence, who called for “every single British soldier” to leave, creating “our first brown dominion, not our last brown colony.”

But unlike the hero of Avatar, (see Going traitor: Avatar versus imperialism) Lawrence never fully broke with his own imperialist masters. Caught between the demands of colonial rule and his admiration for the ‘natives’, he could never resolve the contradiction and died a broken man.

Stewart, following in Lawrence’s footsteps, walked across Asia as a young man and found in the dignity of the locals “a great deal about how to live a meaningful life.” But though admiring the people and recognizing the failings of colonial rule, he remains wedded to the power of which he is part. A prospective Tory candidate, ex-Etonian, diplomat’s son, he has set up a school in Kabul to teach Afghan craftsmen skills to restore old buildings, a pet project of Hamid Karzai’s. Though he calls for troops out of Iraq and Afghanistan, he implicitly believes imperialism capable of arranging the world in gentlemanly fashion, if only it would take on board Lawrence’s “political vision”. Lawrence didn’t question imperialism itself, and Stewart’s Orientalist vision suffers from the same limited horizon.

00:10 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, proche orient, palestine, monde arabe, première guerre mondiale, impérialisme, empire britannique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

T.E. Lawrence’s book Seven Pillars of Wisdom is on the syllabus at the elite US army training college at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Seen as the man who “cracked fighting in the Middle East”, Lawrence is a “kind of poster boy” of how to do colonial rule, according to writer-presenter Rory Stewart, in The Legacy of Lawrence of Arabia (BBC2, Jan 16 and 23 2010).

T.E. Lawrence’s book Seven Pillars of Wisdom is on the syllabus at the elite US army training college at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Seen as the man who “cracked fighting in the Middle East”, Lawrence is a “kind of poster boy” of how to do colonial rule, according to writer-presenter Rory Stewart, in The Legacy of Lawrence of Arabia (BBC2, Jan 16 and 23 2010).

Les commentaires sont fermés.