dimanche, 14 juin 2015

American Capital's Love Affair with Soviet Communism

Our Kind of Enemy

American Capital's Love Affair with Soviet Communism

Ex: http://us2.campaign-archive2.com

Soviet Communism has not been fashionable in elite media and academic circles since 1992. Stalinists are now more often depicted as “conservatives” than leftists, and Communism is seen as a symptom of “nationalism.” A BBC documentary on North Korea declared that country to be a “fascist dictatorship,” on the “right of the political spectrum.” Apparently, if we are to condemn something in the modern world, it must be right-wing.

From a historical perspective, Communism was never really viewed as the enemy by American policymakers. Nationalism was. It has been difficult to discern this, since the true nature and motivations of U.S. policy-making have been shrouded by the myth of the Cold War—the notion that the U.S. and Soviet Union were engaged in an all-or-nothing battle between Freedom and Socialism, with the soul of the world hanging in the balance. In reality, the U.S. and Western Europe invested billions of dollars in the Soviet economy. And at critical times, the USSR was bailed out by cheap grain sales from Archer-Daniels-Midland and other conglomerates.

There was a Cold War of sorts, but it had little to do with “fear of Communism,” which policymakers did not fear nor properly understand. The real antagonism arose when the East sought to create a large, powerful trading bloc outside Western control. Then—and only then—would chatter about “tyranny” and the “Red Menace” be heard. Even in those exceptional times, corporate America continued to invest in “building socialism.”

So it is not entirely surprising to read that President Ford refused to meet with Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, so as not to “prejudice” Brezhnev at a summit held later. Reagan did the same, only meeting with liberal dissidents like Andrei Sakharov. Both Presidents, ostensible “anti-Communists,” were willing to work with Soviets and liberals—but never Russian nationalists.

Sanctions have been put on Putin's Russia that would never have been advocated at the height of the GULAG system. Indeed, the President of Russia has been the target of what scholar Stephen Cohen calls “ongoing, extraordinary, irrational, and nonfactual demonization” from the West. No Soviet dictator was treated so harshly. While Washington was never close to an armed conflict with the Soviet Union, today, a shooting war with Russia is a very real possibility.

The West is deeply indebted, bereft of leadership, and slowly falling into poverty. Yet Washington’s main foreign-policy objectives are to overthrow pro-Russian governments in Uzbekistan, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, and Armenia. At a low point in American legitimacy, Washington is willing to risk a nuclear war.

In such a context, antiwar protests have been conspicuously absent, mainly because the corporate behemoths that financed them during the Cold War are no longer engaged. There is no peace movement calling for negotiation with Russia, just like there is no peace movement protesting the absurd Afghan war. The U.S. engages in provocative war games in Ukraine and Bulgaria with little domestic protest. This would have been unimaginable during the Cold War. The “no nukes” groups no longer exist, precisely at the time where nuclear war is actually possible.

The U.S. defends the “integrity” of Ukraine today, but demanded her independence during the Soviet era. The U.S. sends agents into Ukraine to overthrow the government, but refused to countenance the idea in 1956 or 1968. The U.S. military is lauded, by Left and Right alike, as heroic, superhuman, and morally spotless. Yet soldiers coming home from Vietnam were attacked physically by protesters at the behest of major media. Apparently, for the official Left, we can peacefully coexist with the USSR; however, nationalist (and non-Communist) Russia is a threat to us all.

To understand this mentality, one must turn to the untold story of the Cold War.

The Greatest Open Secret

On December 17, 2014, the Obama administration rescinded the “trade embargo” on Cuba. Many jumped to the conclusion that Cuba was the last front of Washington’s battle against socialism and Marxism. Nothing can be further from the truth. The West built socialism, not only in the early stages but throughout the Soviet period. (Cuba was exceptional, owing mostly to its geography.)

Bolshevik and early Soviet leaders were open about their desire to bring Russia up to speed with the industrialized West and their willingness to collaborate with European and American firms. In turn, Western capitalists envisioned the Revolution and development of Socialism as an opportunity for Russia to enter the global market. Jacob Schiff—of Kuhn Loeb and Company and the founder of the American Jewish Committee—is probably the most notorious Western capitalist who financed Socialism. According to his grandson, Schiff donated some $20 million to Trotsky to finance world revolution, which would amount to a quarter of a billion in today’s dollars.[1] While Schiff was eager to overthrow regimes (such as Tsarist Russia) that he viewed as threats to the Jewish people worldwide, other American capitalist saw Bolshevik Russia as an investment opportunity.

A key to understanding this relationship between Big Business and Communism is the Congressional Overmann Commission of 1919, a document that is universally ignored by standard texts on the Cold War. The Overmann Commission was called, in large part, to gauge the opinions of American capitalists regarding the USSR. The consensus was that it was quite positive.

One who testified was Roger Simmons, from Hagarstown, Maryland, who was in a Commerce Department Mission in the USSR as Trade Commissioner with the Red State. He was there for 11 months in the transitional period. His entire purpose was to help build the Soviet Union through grants and raw materials from the U.S. He attended a huge business consortium taking place in Grand Rapids, Michigan, where about 800 businessmen were deciding how best to begin investing in the USSR. He spoke of their “misinformed” admiration for the Soviet Union and the potential for profit there. [2]

George A. Simons, the head of the Methodist Mission to Petrograd, noted, “I have a firm conviction that this thing is Yiddish, and one of its bases is in Brooklyn, NY” [3]. (It’s worth noting that Simons said this even though he publicly disavowed anti-Semitism.)

Raymond Robbins, who was part of the Red Cross in Petrograd and elsewhere from 1917-1918, described the work of William Thompson, a wealthy banker negotiating loans for the Soviet government, who used the Petrograd branch of the National City Bank to funnel about 12,000,000 rubles to the revolutionaries (not merely the Bolsheviks), which was, in 1918, about $1 million. Moreover, he was speaking to the Red Cross about coordinating an infrastructure for an entire set of new newspapers supporting the revolutionaries.

What becomes clear in the testimony is that even the most motivated Americans had no idea who was who. There was a sense that there were leftist “revolutionaries,” and that's where the bulk of foreign money went. The Red Cross was granted about $3 million monthly, from both private and state sources in America, to “interpret the revolutionary groups to the army and to peasant villages of how absolutely indispensable to save the revolution to keep the front and defeat the German militarist autocracy.”[4]

This dirty secret of western economics is rarely mentioned, let alone analyzed, by major historians. One of the few is TW Luke writes, who studied Soviet technology.

The Bolsheviks stressed to Soviet workers, managers, and intellectuals the centrality of industry over agriculture in the NEP of 1921. Trotsky notes, 'We [the Soviet Union] are in a process of becoming a part, a very particular part, but nonetheless an integral part of the world market . . . Foreign capital must be mobilized for those sectors of [Soviet] industry that are most backward.' . . . These technological imports were to be limited because the Bolsheviks recognized the dangers of dependencies on the core, especially technological dependence. For example, resolutions of the 14th Party Congress in 1925 stressed the 'whole series of new dangers' in Western trade and advocated domestic technical development to prevent the USSR from becoming, in Parrot's words, 'an appendage of the capitalist world-economy'. Still, as Sutton notes 'the penetration of early Soviet industry was remarkable, Western technical directions, consulting engineers and independent entrepreneurs were common in the Soviet Union.' Even so, throughout the 1920s the Soviet state tightly regulated foreign access to suit its technological needs.[5]

Not only did the U.S. and Western Europe build the USSR, but did so as their own populations were struggling. The West was so involved in the development of the USSR that the 14th Party Congress, mentioned above, was concerned about the loss of Soviet independence.

Luke continues,

The impact of imported technologies differed from industry to industry and from region to region. In the oil industry, for example, they were vital. Petroleum exports in 1926-1927 doubled 1913 exports. Alone, they provided 20 percent of Soviet foreign exchange earnings: 'the importation of foreign oil-field technology and administration, either directly or by concession, was the single factor of consequence in this development (Sutton, 1968:43). While the overall imports of expertise and technology dropped in value from the 1893-1913 levels, the Bolsheviks' bureaucratically planned economy stressed the need for post-1918 imports to be directed toward cost-efficient and economically necessary production to fit the planned industrial program of the regime. [6]

In no other war (“cold” or otherwise) did combatants feverishly invest in building up their opponent.

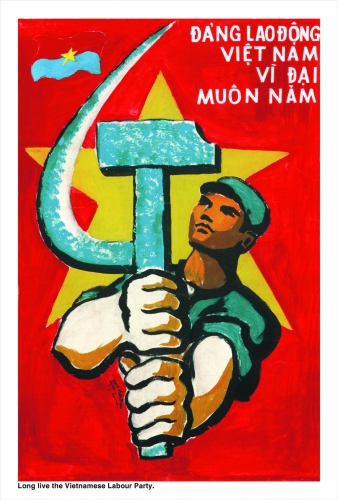

Had the West not subsidized the USSR, Communism would likely not have survived. Stalin himself admitted that two-thirds of early Soviet industrial products and development were of American origin.[7] Trade and aid to the USSR were constant and often included the most advanced technology available. There were no meaningful sanctions on the USSR throughout most of its history. Hence, the Cuban embargo or the Vietnam War had little to do with Marxism or the USSR. The fact is that the infrastructure of Castro and Ho Chi Minh was largely produced in the US.

The propulsion systems for much of the Soviet Navy and, significantly, at Haiphong Harbor were from American firms. Nixon and Johnson actively went out of their way to stop any move to stifle trade with the USSR, even in the midst of the Vietnam War. The Gorki Truck plant was shipping hundreds of vehicles a month to North Vietnam, with the full blessing of the State Department. It was, of course, a Ford Motors plant, and it was largely staffed by Americans. Henry Ford created the Soviet automotive industry, especially in the development of trucks. His Gorki plant was also making rockets and other military equipment for the USSR, without comment from Washington. Soviet rockets were fired on Ford GAZ-69 chassis.[8]

In 1968, Fiat motors created the world's largest automotive plant in the world at Volgograd. ZIL was created by New Britain Machine Company. In 1972, Nixon personally approved the Kama truck plant deal, the creation of an automotive and trucking plant manufacturing 100,000 vehicles per year, which at the time was more than all U.S. automakers combined. The plant itself came to occupy 36 square miles, every inch created by the U.S.[9]

In Korea, the North Korean Army and China were using trucks made by Ford and tractors by Caterpillar. Soviet fighters were equipped with Rolls Royce engines sent to Stalin by the British automaker. As Anthony Sutton explains, it was the elite, including Maurice Stans, Peter G. Peterson, Peter Flanigan, Averell Harriman, and Robert McNamara, that created the infrastructure for constant and lucrative trade with the “enemy.”[10] The Ural Steel complex that served as the heart of Soviet industrialization was “100% American.” The McKee Corporation built the world's largest steel and iron plant in the world in the USSR:

Organization methods and most of the machinery are either German or American. The steel mill “Morning” near Moscow, is said to be one of the most modern establishments of its kind in the world. Constructed, organized and started by highly paid American specialists, it employs 17,000 workers and produces steel used by motor plants, naval shipyards and arms factories. [11]

The 1932 KHEMZ plant in eastern Ukraine was created by GE, and was 250 percent larger than anything GE had in the U.S.

Anthony Sutton writes:

Major new units built from 1936 to 1940 were again planned and constructed by Western companies. Petroleum-cracking, particularly for aviation gasoline, as well as all the refineries in the Second Baku and elsewhere were built by Universal Oil Products, Badger Corporation, Lummus Company, Petroleum Engineering Corporation, Alco Products, McKee Corporation, and Kellogg Company.[12]

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York sent $1 billion in aid to Trotsky and the Red Army.[13] The First Five year plan had all of its military equipment built by American firms. Sergei Nemetz of Stone and Webber, along with Zara Witkin, supervised most of the military construction for the first two Five-Year Plans, using American capital desperately needed at home. Carp Exports, based in New York City, supplied the Soviet Union with all its high-tech military parts. Electric Boat Company of Groton, Connecticut built the Soviet submarine fleet with express permission of the State Department in 1939. Skoda Armaments of Czechoslovakia was a subsidiary of the Simmons Machine Tool Corporation of Albany, New York. Ball bearings were built in the USSR by Bryant Chucking Grinder Company of Springfield, Vermont.

All told, 90 percent of all Soviet industry was created in the U.S. or Western Europe.

What such a history reveals is that capital does not require markets in order to be profitable. The Western financial elite saw the Soviet system as a perfected version of itself: a totally centralized economy run by experts from one source. Capital looked upon Gosplan—the USSR’s central planning committee—with envy; and it was so similar in its powers to the small group of financial conglomerates that governs the U.S. economy in 2015. The Gosplan board approved investments, set targets, measured economic growth, dictated the amount of money in circulation, manipulated statistics—down to the last detail. This system is little different, institutionally or ideologically, from the American financial elite and the Federal Reserve Board, which organizing the American economy, with remarkable freedom from markets and the influence of politicians.

Once one rejects the formulaic division of the world into “Soviet” and “American” camps, all of 20th-century history appears differently.

One of the most telling quotations is from a Russian-language work, The Political History of the Russian Emigration, written by SA Alexander:

Despite the growing popularity of the right wing in the émigré environment, it is only the leftists that found a response in Western governments. Most significantly, the leftists in exile were feted by the financial and industrial sector interested in trade with the Soviet Union. The “All Emigre Russian Unity” conference was called at the behest of American capital, and the Soviet financial elite were invited. Conferences subsequent to this were called by capital in Cannes, Genoa, The Hague and Lausanne.[14]

Apparently, U.S. capitalists rarely feared Soviet advances.

As an ally of the victorious capitalist core powers, the USSR gained many unexpected technological windfalls in the aftermath of World War II. New technical inputs in weaponry, electronics, nuclear power, aircraft, and chemicals were expropriated from Germany and other Axis powers from 1945 to 1950. Allied Lend-Lease equipment, especially heavy bombers and airplane engines, was also 'reverse engineered' from 1942 to 1953. The USSR dismantled and shipped home 25 percent of the industrial plants in the Western zones of Germany, along with additional industrial equipment constituting 65 percent of all motor vehicle production, 75 percent of all rubber tire capacity, and 40 percent of all paper and cardboard-producing capacity in eastern Germany.[15]

This is extremely significant in that these patents were at least in part financed by American firms. They represent decades of research and millions of dollars in grants. Yet, Stalin brought them home without a peep from the West.

The Vietnam Era

Between 1965 and 1985, the Soviet Union, Cuba, Vietnam and the rest of the Soviet Bloc was given tremendous boosts by American firms. Alcoa built Soviet aluminum. American Chain and Cable created the machine-tool industry. Ingersoll Rand built much of the heavy-duty transport infrastructure (under Automatic Production Systems, a shell company). Betchell created the construction industry. Boeing was heavily invested in Soviet aviation, while, at the same time, building the bulk of the American Air Force. Dow Chemicals, DuPont, and Dresser industries were competing to see who would build the more advanced Soviet chemical plants. IBM helped create the modern computer industry, while Gulf General Atomic was helping put nuclear missiles together for the USSR.

Much of this was made easier in the 1980s by the U.S.-USSR Trade and Economic Council, a pet project of then-Vice President George H.W. Bush and Commerce Secretary Malcolm Baldrige. Just a partial list of members include Abbott Laboratories, Allen Bradley Gleason Corporation, Allied Analytical Systems, Ingersoll Rand, International Harvester, Kodak, American Express, Archer Daniels Midland, Armco Steel, Monsanto, Cargill, Occidental Petroleum, Caterpillar, Chase Manhattan, Pepsi Co., Chemical Bank, Phibro-Salomon, Coca Cola, Ralston, Continental Grain Seagram, Dow Chemical, and Union Carbide. All members of this Council had substantial investments in the “Soviet enemy” and, through their philanthropic organizations, created the “peace movement.”[16]

In 1985, the San Jose Mercury News reported confirmation from State and Commerce Departments that “[t]he most sensitive, state-of-the-art semiconductor manufacturing equipment went to the Soviet Union after first being shipped to Switzerland.

Creed [spokesman for Commerce] said the material shipped to Cuba, and additional equipment the Cubans were unable to obtain, would have given them the capability to produce semiconductors and integrated circuits. The report stated that such trade was “illegal.”[17]

The State Committee of the Council of Ministers of the USSR sealed a huge deal with Data Control in 1973. While openly denying it in public, Norris and the Department of Commerce squashed all inquiries into the investment and aid project. The Soviets stated that Data Control will “[b]uild a plant for manufacturing mass storage devices based on removable magnetic disk packs with up to 100 million byte capacity per each pack.”

The brunt of the Soviet computer industry was created by American firms. In 1959, the Model-802 system was sold to the USSR from Elliot Automation ltd., an English firm. This was part of General Electric, one of the major offenders in this category. European branches of US firms were selling advanced computer equipment to the USSR at roughly $40 million per year.

During the Vietnam War, giants such as Union Carbide, General Electric, Armco Steel, Bryant Chucking Grinder, and Control Data were just the wealthiest of American capitalists with regular deals in building Soviet industry. This was in 1973, and every bit of it was approved by Johnson and Nixon during the war.

Conclusion

By the 1950s, the Soviets had educated enough of their own in Western methods of production such that they achieved a great deal of independence in most every sector of the economy. Regardless, the USSR was fed on a constant stream of food from American capitalists; American universities praised the USSR as a matter of course (or some form of socialism); and all major capitalists enterprises were invested in the USSR and satellite states. Both before and after Stalin's Great Purges, the U.S. was contributing massively to the Soviet industrialization drive and the creation of its “experimental” economy. When the Cold War got hot, such as during the Vietnam conflict, Washington was never motivated by “anti-Communism” but the fear in the breasts of American business that if China and Russia were to combine forces, the U.S. might become superfluous.

- New York Journal—American, February 3, 1949. ↩

- Overmann, Congressional Record, 294, 304; all pages come from the Report itself. ↩

- Ibid., p. 112. ↩

- Ibid., 777. ↩

-

Luke, TW (1983), “The Proletarian Ethic and Soviet Industrialization,” American Political Science Review 77 (3): 588-601, drawing from Antony Sutton, The Best Enemy Money Can Buy (Montana: Liberty House Press, 1986, Dauphin Publications, 1991),

http://reformed-theology.org/html/books/best_enemy/index.html. ↩

- Ibid., 339-340, also drawing on Sutton. ↩

- Chase-Dunn, C, “Socialist States in the Capitalist World Economy,” Social Problems 27(5), 1980: 505-525. ↩

- See Sutton, The Best Enemy Money Can Buy. ↩

- See Berliner, The Innovation Decision in Soviet Industry (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1976). ↩

- All evidence from the State or Commerce Departments has not been declassified. Only through insistent demands have these documents been granted to the public. It is highly likely that the unclassified papers from 70 years ago are largely detailed agreements between American capital and the Soviet Union. ↩

- U.S. State Dept. Decimal File, 861.5017, Living Conditions/456, Report No. 665, Helsingfors, April 2, 1932 ↩

- Sutton, Western Technology and Soviet Economic Development: 1945–1965, Chapter 4 (Stanford, CA: The Hoover Institution, 1973). ↩

- Washington Post, Feb. 2, 1918. ↩

- S. A. Aleksandrov, Politicheskaia istoriia zarubezhnoi Rossii, http://www.rovs.atropos.spb.ru/index.php?view=publication&mode=text&id=17, translation by the author. ↩

- Luke, “The Proletarian Ethic and Soviet Industrialization,” American Political Science Review 77 (3), 1983: 588-601. ↩

- Erikson, 1991. ↩

- There is no evidence that any law against such a practice existed. Even if it did, it would have made little difference, since the technology would have already been transferred. ↩

00:05 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, états-unis, urss, capitalisme américain, système soviétique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les commentaires sont fermés.