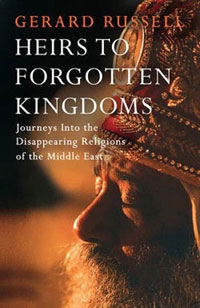

Interview with Gerard Russell on Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms

Ex: http://www.onreligion.co.uk

Former British diplomat, Gerard Russell, has published a work looking at the minority religions in the Middle-East.

Former British diplomat, Gerard Russell, has published a work looking at the minority religions in the Middle-East.

Abdul-Azim Ahmed speaks to him.

AA: Thank you Gerard for speaking to us about your book. Could you begin by telling us a bit about yourself?

GR: Sure. I’m a former British diplomat. I’ve been in the Middle East for many years and I learned Arabic. I’ve lived in Cairo, Jerusalem, Baghdad, Jeddah, and Kabul. In each of these places I had encountered these little religions, little communities, which when I looked at them, seemed to have preserved remarkably intact elements of much earlier trends and traditions of human thought. You see these communities, you think ‘this is amazing, this is history alive in the present day!’

AA: Can you tell me more about the religions you looked at, and where they come from geographically?

GR: I looked mainly at the places where I had lived and where I could say something that others perhaps couldn’t. So in Egypt I looked at the Copts, likewise Palestine for the Samaritans – Palestine-Israel I should say particularly as they are the original Israelites. I looked at Lebanon for the Druze, Iraq for the Yazidis and Mandaeans, Iran for the Zoroastrians and also I looked at Pakistan for an outlier group which is very different from the others, which is the Kalasha who live in Chitral in Pakistan.

AA: There was a very gruesome and unfortunate way in which the topic you look at gripped the headlines. In the summer of 2014, the self-styled Islamic State besieged a community of Yazidis in Iraq, and many were asking the question ‘who are the Yazidis?’ Naturally you were well placed to answer.

GR: That’s right. It’s not the first time that the Yazidis have been exposed to this kind of horror. In 2007 there was a massive terrorist attack which killed over 700 of them in Sinjar. So there is something of a history of this. Although it is important to remember that between the Ottomans (who as late as 1880s were behaving abominably to the Yazidis) and the al-Qaida attack in 2007, there was actually a prolonged period of mutual coexistence and inclusion. Egypt 1860 to 1920 is also a good example. There is a very clear trend in those times in which people of all religions in the Middle-East behaved to each other more decently than was sometimes the case in Europe during that era. That is important to remember because the narrative says ‘Muslims are uniquely intolerant’ which simply isn’t true; the reality is that the Middle-East was ahead of Europe in including its Christian and Jewish minorities for many years. The fact that it appears so negative now by comparison, is a product of particular circumstances – it is not inevitable at all!

AA: From that contemporary context, it is interesting to look at the roots as you mentioned. For myself, I find the Mandaeans and Yazidis especially intriguing, because they seem to echo a familiar theology of the three Abrahamic faiths, but have stark differences also. How was your experience of this?

GR: One thing that is interesting about the Mandaeans is that they recognise certain Jewish prophets such as Noah, but not Abraham. So you might think that is peculiar, because Abraham is the patriarch, but in fact they have this in common with many religions of two millennia ago. To the ascetics of the Middle-East, those who wanted a strict morality, they read about Abraham and they weren’t very impressed. The Mandaean rejection of Abraham is interesting because it connects us to that historic era, which is when the Mandaean religion was conceived.

The Mandaeans have an almost impenetrable demonology and cosmology written in their language, which is Babylonian Aramaic. Some of their rituals are thought provoking, such as the tradition of the priest staying awake for seven days and seven nights without eating to become ordained. Likewise, to become a bishop, you have an amazing ceremony where a message is sent to ‘other side’ through a dying person, to gain permission for this particular person’s appointment. Fascinating ideas. Sometimes when I read about these, it really makes me reflect and not just as ‘wow, this is really old’ but ‘wow, this is an interesting concept’. The Yazidis’ belief in Melek Taus is one such thing.

AA: Well maybe that is a point to pick up on. There is a certain familiarity, certainly for Muslims, with the cosmology of the creation of Adam and Eve, of the angels, of the role of Satan. But of course the Yazidis have a much more idiosyncratic understanding of Melek Taus who is associated with the fallen Archangel Iblis. Could you elaborate a bit more on that? It is an almost subversive take on traditional Quranic readings.

GR: Yes, it really is, when you look at certain aspects of Yazidi belief. For example, Melek Taus – he appears to be the Archangel Azazel, or Lucifer, or Iblis as he is called in Islam. The Yazidis use the term Iblis, but not Shaitaan which they see as insulting and in fact it is a taboo.

The Yazidis, like Muslims, believe Iblis rebelled against God, but unlike Muslims, Yazidis believe he was forgiven. That said, if you look back to the ninth century, there were a lot of Sufi movements that explored the idea of Satan in a way that wasn’t entirely hostile. The Islamic saint Rabia al-Basra said she wanted to quench hell, to extinguish the fires of hell, so that none would be good out of fear of punishment. The Yazidis actually say that the fires of hell have been quenched by the tears of Melek Taus’. It is in one sense a radical departure from the Islamic tradition, but in another sense, it is not a million miles away from what some Muslims have sometimes believed.

AA: That similarity, outwardly at least, is comparable to the Samaritans and the Jewish religion. Many people will be familiar with the story of the Good Samaritan, but unaware of the history of the people and their religion.

GR: The Samaritans have a great advocate who travels the world called Benny Tsedaka. They are interesting as they are both Palestinian and Israeli by nationality and politically – this is unique. Although to the outside world they look simply Jewish, it is much complex than that. The word Jewish comes from Judea and the tribe of Judah. The Samaritans are the descendants of a different people from the Northern Kingdom of Israel, supposedly wiped out by the Assyrians in the seventh century BCE. So they see themselves as being a separate people. They are not accepted by traditional Jewish Rabbis who do not regard them as ‘kosher’, as being part of the people of Israel.

The thing that really distinguishes them from Judaism is that whereas the Jews were scattered by the Romans, the Samaritans were largely left alone. It seemed like a blessing to them at the time. Interestingly though, the consequence is that now they almost don’t exist. They never really adjusted to living in diaspora. They have kept the old traditions exactly as they were. They still have a priestly caste, they still have sacrifices, and they keep The Law incredibly strictly. They almost became extinct as there were fewer than 30 of them at one point whereas there are now 771. So they have shown an amazing resilience.

One thing to remember about these religions is that people have predicted their extinction many times before, but they have been proven wrong, they have remarkable resilience. People in the 1840s saying the Druze will no longer have Chiefdoms in Lebanon, well they do. They said in the 1880s the Samaritans won’t last much longer, well they did. Politics changes – the mood can be hostile one year and then ten years later it may not be.

AA: That is a sobering thought, but positive too. That these religions may be more permanent than the transient politics of the region, and may outlive these contemporary catastrophes we see. Moving away from the Levant and Iraq to the Kalasha in Pakistan – could you tell us some more about them? They seem like another tradition that has survived despite the odds.

GR: These groups of course survived for many reasons, among them that there is a willingness in Islam for coexistence, or toleration at least, of other religions. But there were often geographical reasons – such them living in marshes or mountains. Often a conquering force would simply resign themselves to not enter a particular piece of land because it was simply too difficult.

In the case of the Kalasha, they lived in the great mountains of the Hindu Kush. There used to be a whole collection of tribes in that region who practiced what we could describe as an antique form of paganism. It really does involve many gods and sacrifices, ceremonies and dance, wine drinking too! They survived for a long time because of the mountains, and even Tamerlane, who was one of the few who did want to go around and convert people by force, couldn’t subdue them.

A few remaining Kalasha live in Chitral on what are now good terms with the local authorities. It has been a mixed history however. You can read some incredibly passionate books in defence of the Kalasha by Pakistani intellectuals. There were some individuals, particularly a local cleric who wanted to convert them in the 1950s, but they have survived.

AA: Taking a step back, there is a question I have which I wonder if you can shed some light on – is there a particular reason why the Middle East has a larger amount of religious diversity than Europe?

GR: That is a great question. There are a few reasons. One is that it has a very deep past. When Christianity and Islam arrived, the Middle East already had other deeply embedded religions which had philosophies which were very sophisticated and therefore more resistant to conversion than the equivalent in Europe.

The second reason is that historically the Arab Muslims who conquered those areas, they had to establish their own authority while having their own distinct religion. So they didn’t put emphasis on conversion, but they wanted acent for their rule. When Christianity came into Europe, it came via the Romans who had already ruled Europe for 300 years, they didn’t need to be as tolerant.

The third thing, which is partly related to that, is that Islam was quite accepting of other religions (I don’t mean to exaggerate – in actual behaviour, it was very similar to the Christianity in Western Europe) but what was unusual about Islam was that it had this greater level of acceptance of other faiths because of the Quran making it explicit these religions were respected, and this respect extended to religions that you might not immediately think about, such as the Mandaeans, also called the Sabians. And so I think it does prove something very important which is that the history of Islam, in particular the history of Islam when it was at its height in terms of culture and technology, when Baghdad was the capital of the world and the leading civilisation, was a history of religious diversity.

AA: Thank you very much for your time Gerard.

Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms by Gerard Russell is available for purchase online and in bookstores.

Enjoyed this article? Then please subscribe. It helps us to keep producing quality British religious journalism.

Le déni des cultures est un déni anthropologique grave, qui conduit, à terme, à une inintelligibilité du monde semeuse de tensions et de conflits. Le déni des cultures est un déni du réel.

Le déni des cultures est un déni anthropologique grave, qui conduit, à terme, à une inintelligibilité du monde semeuse de tensions et de conflits. Le déni des cultures est un déni du réel.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

In the spring of 2006, Gerard Russell was a bored British diplomat stewing in the heat of the Green Zone in Baghdad, “a five-mile 21st-century dystopia filled with concrete berms and highway bridges that ended in midair where a bomb had cleaved them”. Then he received a call from the high priest of the Mandeans.

In the spring of 2006, Gerard Russell was a bored British diplomat stewing in the heat of the Green Zone in Baghdad, “a five-mile 21st-century dystopia filled with concrete berms and highway bridges that ended in midair where a bomb had cleaved them”. Then he received a call from the high priest of the Mandeans.

Moreover, the integration initiatives in Eurasia are not limited to the EEU, the Silk Road Economic Belt and the SCO. In this context, the Eurasian initiative of South Korean President Park Geun-hye, Kazakhstan’s ‘Nurly Zhol’ programme and Mongolia’s Steppe Route project are also worth mentioning. The fundamental difference between all of these projects and the TTP and TTIP projects being promoted and financed by the US is as follows. The main objective of the TPP and TTIP (besides subordinating the member countries’ economies) is to impede the economic growth of the leading Eurasian countries, primarily China and Russia, and prevent their integration into the Asia-Pacific Region and Eurasia. Thus the TPP and TTIP initiatives are exclusive, they deliberately exclude America’s main economic and political rivals. In contrast, the EEU, the Silk Road Economic Belt, the SCO and all the other projects and initiatives mentioned above are by definition inclusive. They are not only open to participation by all the countries in the region, but would simply be unrealisable if just one of the countries located in an area where major infrastructure projects were being implemented was unable, for whatever reason, to take part.

Moreover, the integration initiatives in Eurasia are not limited to the EEU, the Silk Road Economic Belt and the SCO. In this context, the Eurasian initiative of South Korean President Park Geun-hye, Kazakhstan’s ‘Nurly Zhol’ programme and Mongolia’s Steppe Route project are also worth mentioning. The fundamental difference between all of these projects and the TTP and TTIP projects being promoted and financed by the US is as follows. The main objective of the TPP and TTIP (besides subordinating the member countries’ economies) is to impede the economic growth of the leading Eurasian countries, primarily China and Russia, and prevent their integration into the Asia-Pacific Region and Eurasia. Thus the TPP and TTIP initiatives are exclusive, they deliberately exclude America’s main economic and political rivals. In contrast, the EEU, the Silk Road Economic Belt, the SCO and all the other projects and initiatives mentioned above are by definition inclusive. They are not only open to participation by all the countries in the region, but would simply be unrealisable if just one of the countries located in an area where major infrastructure projects were being implemented was unable, for whatever reason, to take part.